Oral allergy syndrome (OAS), also known as pollen-food allergy syndrome, is one of the most common food allergies in adults and affects up to 70% of patients with allergies to pollen.

123 The most extensively studied model of OAS is the so-called birch-apple syndrome, in which eating apples causes itching and hives in the mouth.

45 Birch-apple syndrome is explained by the high structural homology between the major birch allergen Bet v 1 and the major apple allergen Mal d 1.

46 Taking into account the homology between the major allergens from birch and apple, it is reasonable to hypothesize that immunotherapy with birch pollen extract would improve apple allergy.

4 Indeed, previous studies have shown that pollen-specific immunotherapy could reduce OAS in patients with pollen-induced allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (ARC).

47891011 Nevertheless, at present, there is no consensus on the effectiveness of immunotherapy for OAS. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) with Fagales pollens on the symptoms of OAS and ARC by measuring improvement in weighted symptom scores after SCIT. This study got permission from Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB Number: 4-2013-0397).

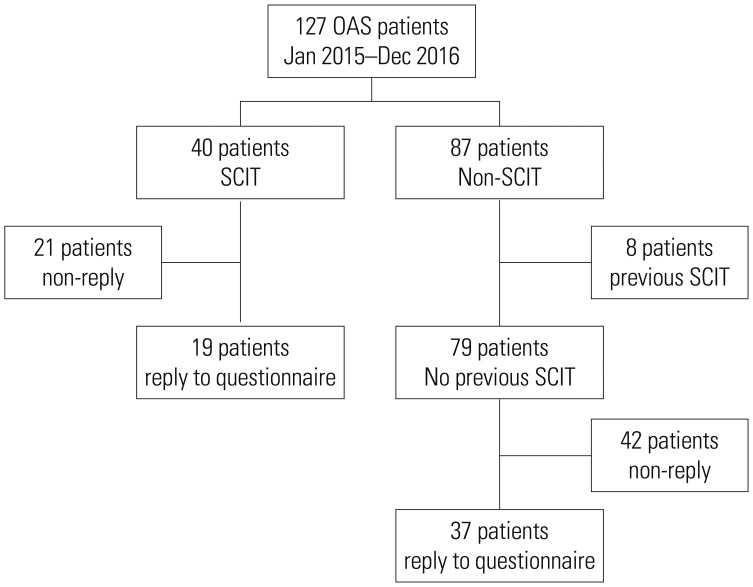

We screened 127 patients over 15 years of age with OAS who visited the Allergy Asthma Center at Severance Hospital in Seoul, Korea from January 2005 to December 2016. OAS was diagnosed on the basis of a history of seasonal pollen allergy, results of a skin prick test (SPT) or measurement of serum IgE (sIgE) by ImmunoCAP® (ThermoScientific, Uppsala, Sweden), and a review of patient medical records. We considered SPT positive if the wheal size of an allergen was larger than 3 mm, compared to negative control, and ImmunoCAP sIgE positive if the concentration was higher than 0.35 kU/L. SCIT was administered with aqueous extracts of birch and oak pollens (Hollister-Stier, Spokane, WA, USA). Patients were injected with a mixture of oak and birch pollen extracts with mean maintenance doses of 0.34 mL at a concentration of 1:200 weight/volume for birch and oak at every 4 weeks. The duration of SCIT varied from 82 days to 1735 days, with an average of 792.4 days. Of the 127 patients with OAS, 40 were treated with SCIT and the other 87 were not. Eight of the 87 patients who did not receive SCIT during the study period were excluded because of a previous history of SCIT. We included 56 patients who could be contacted by phone from December 2016 to February 2017 to answer a questionnaire about their culprit fruits or vegetables and the presence and improvement of OAS and ARC symptoms. Nineteen of those patients received SCIT for allergens including Fagales pollens, and the other 37 patients did not receive immunotherapy. This study was approved by Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 2013-0397). The patients' dispositions are summarized in

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion of participants. SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; OAS, oral allergy syndrome.

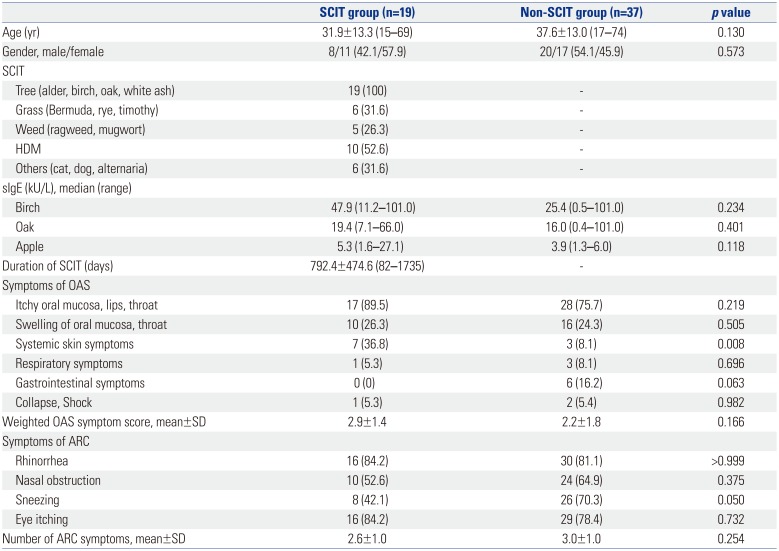

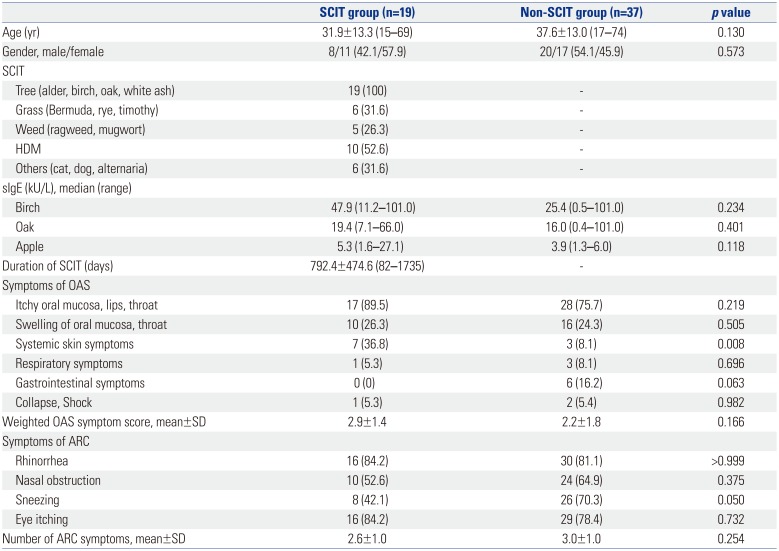

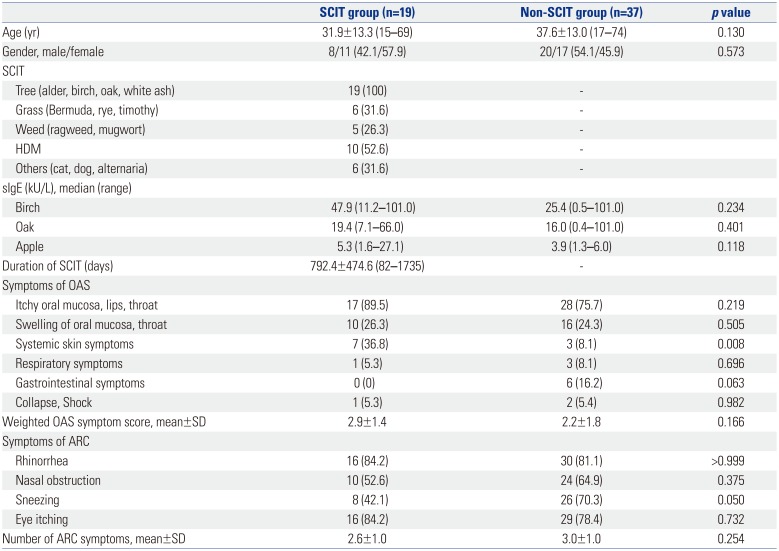

The clinical features of the 56 patients are shown in

Table 1. One of the patients that received SCIT and three of the patients that did not receive SCIT had experienced anaphylaxis due to fruit at the time of diagnosis. The mean weighted OAS symptom scores were not different between the patients that received SCIT and those that did not take IT. Although the tests for allergen-specific IgE (sIgE) were performed according to the OAS or seasonal ARC symptoms of each patient, we preferentially checked the results for sIgEs for birch, oak, and apple for the purposes of this study.

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with OAS

|

SCIT group (n=19) |

Non-SCIT group (n=37) |

p value |

|

Age (yr) |

31.9±13.3 (15–69) |

37.6±13.0 (17–74) |

0.130 |

|

Gender, male/female |

8/11 (42.1/57.9) |

20/17 (54.1/45.9) |

0.573 |

|

SCIT |

|

|

|

|

Tree (alder, birch, oak, white ash) |

19 (100) |

- |

|

|

Grass (Bermuda, rye, timothy) |

6 (31.6) |

- |

|

|

Weed (ragweed, mugwort) |

5 (26.3) |

- |

|

|

HDM |

10 (52.6) |

- |

|

|

Others (cat, dog, alternaria) |

6 (31.6) |

- |

|

|

sIgE (kU/L), median (range) |

|

|

|

|

Birch |

47.9 (11.2–101.0) |

25.4 (0.5–101.0) |

0.234 |

|

Oak |

19.4 (7.1–66.0) |

16.0 (0.4–101.0) |

0.401 |

|

Apple |

5.3 (1.6–27.1) |

3.9 (1.3–6.0) |

0.118 |

|

Duration of SCIT (days) |

792.4±474.6 (82–1735) |

- |

|

|

Symptoms of OAS |

|

|

|

|

Itchy oral mucosa, lips, throat |

17 (89.5) |

28 (75.7) |

0.219 |

|

Swelling of oral mucosa, throat |

10 (26.3) |

16 (24.3) |

0.505 |

|

Systemic skin symptoms |

7 (36.8) |

3 (8.1) |

0.008 |

|

Respiratory symptoms |

1 (5.3) |

3 (8.1) |

0.696 |

|

Gastrointestinal symptoms |

0 (0) |

6 (16.2) |

0.063 |

|

Collapse, Shock |

1 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

0.982 |

|

Weighted OAS symptom score, mean±SD |

2.9±1.4 |

2.2±1.8 |

0.166 |

|

Symptoms of ARC |

|

|

|

|

Rhinorrhea |

16 (84.2) |

30 (81.1) |

>0.999 |

|

Nasal obstruction |

10 (52.6) |

24 (64.9) |

0.375 |

|

Sneezing |

8 (42.1) |

26 (70.3) |

0.050 |

|

Eye itching |

16 (84.2) |

29 (78.4) |

0.732 |

|

Number of ARC symptoms, mean±SD |

2.6±1.0 |

3.0±1.0 |

0.254 |

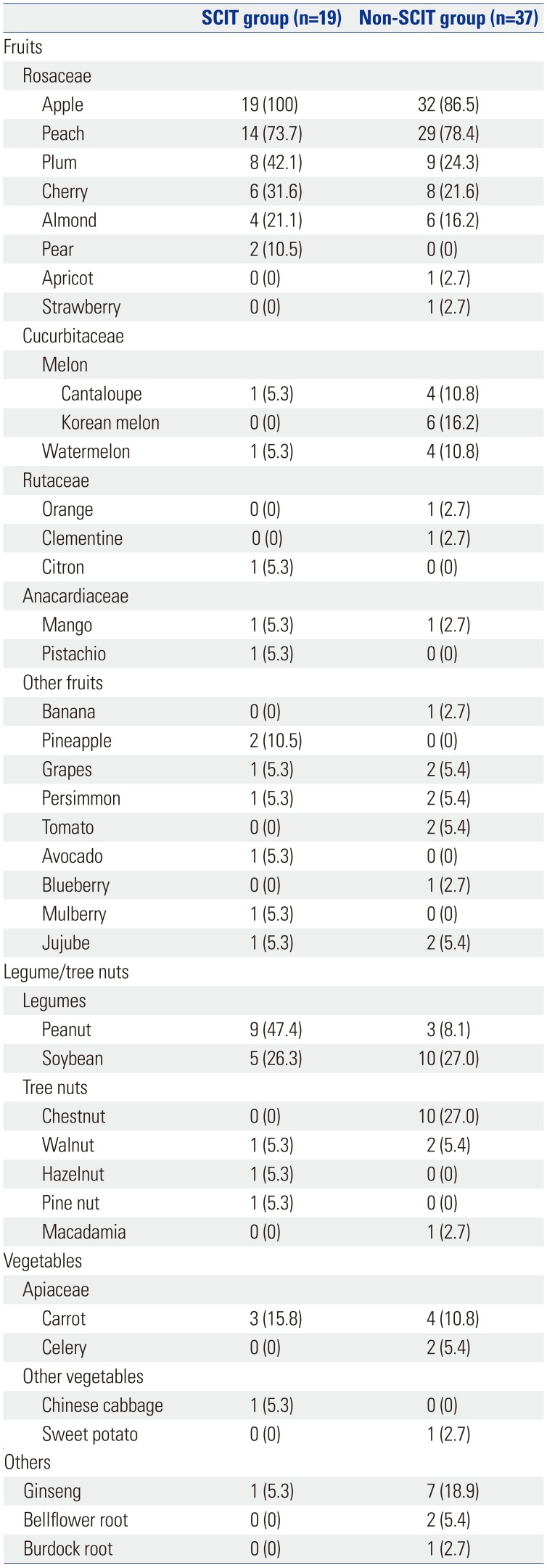

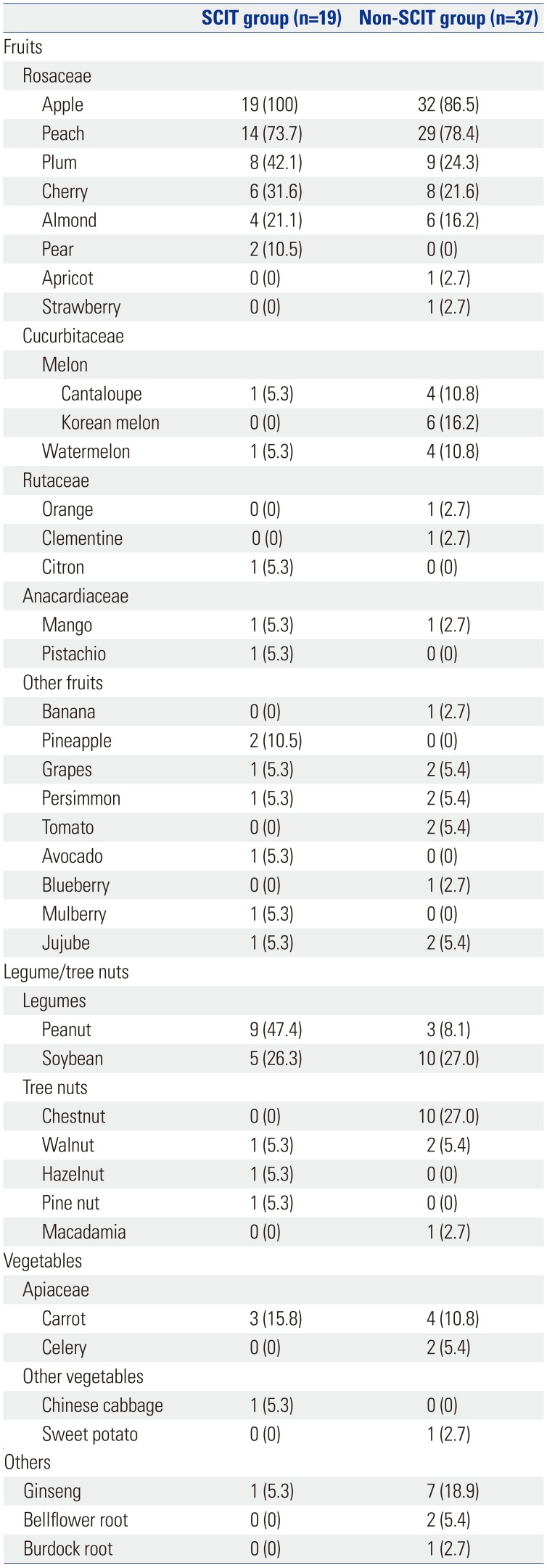

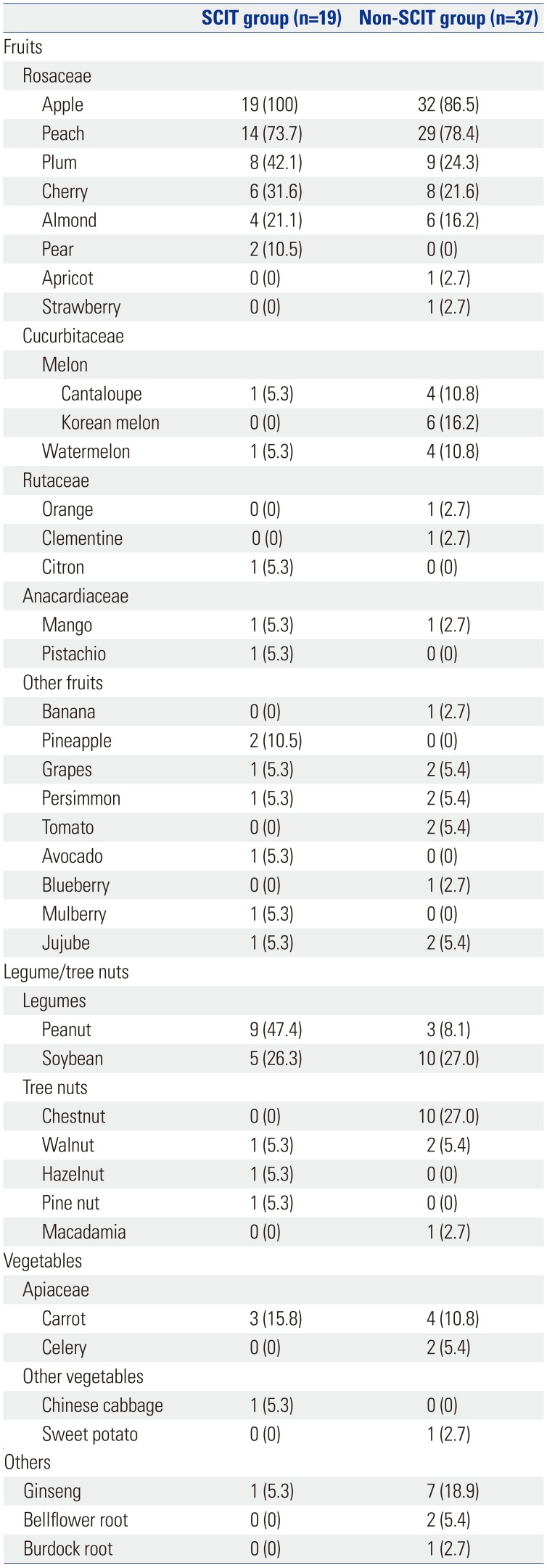

The culprit foods causing OAS symptoms included fruits, nuts, vegetables, and others (

Table 2). All 19 patients (100%) that received SCIT and 32 of the 37 patients (86.5%) that did not receive IT had OAS symptoms due to apples. The most common cause of OAS was apples in both groups of patients. In addition, patients had OAS symptoms due to various other fruits of the Rosaceae family, including peaches, plums, cherries, almonds, pears, apricots, and strawberries. Other triggering foods were fruits of the Cucurbitaceae family (e.g., melon, watermelon), the Rutaceae family (e.g., orange, clementine, citron), the Anacardiaceae family (e.g., mango, pistachio), and others. Legumes, such as peanuts or soybeans, and tree nuts, including chestnuts, walnuts, hazelnuts, pine nuts, and macadamia, also triggered OAS symptoms. Some patients also suffered from allergies to carrots, celeries, Chinese cabbage, and sweet potato. Because of the unique dietary culture of Korea, ginseng, bellflower root, and burdock root were also included among the offending foods.

Table 2

Offending Fruits, Nuts, Vegetables, and Other Foods for Oral Allergy Syndrome

|

SCIT group (n=19) |

Non-SCIT group (n=37) |

|

Fruits |

|

|

|

Rosaceae |

|

|

|

Apple |

19 (100) |

32 (86.5) |

|

Peach |

14 (73.7) |

29 (78.4) |

|

Plum |

8 (42.1) |

9 (24.3) |

|

Cherry |

6 (31.6) |

8 (21.6) |

|

Almond |

4 (21.1) |

6 (16.2) |

|

Pear |

2 (10.5) |

0 (0) |

|

Apricot |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Strawberry |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Cucurbitaceae |

|

|

|

Melon |

|

|

|

Cantaloupe |

1 (5.3) |

4 (10.8) |

|

Korean melon |

0 (0) |

6 (16.2) |

|

Watermelon |

1 (5.3) |

4 (10.8) |

|

Rutaceae |

|

|

|

Orange |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Clementine |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Citron |

1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Anacardiaceae |

|

|

|

Mango |

1 (5.3) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Pistachio |

1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Other fruits |

|

|

|

Banana |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Pineapple |

2 (10.5) |

0 (0) |

|

Grapes |

1 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

|

Persimmon |

1 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

|

Tomato |

0 (0) |

2 (5.4) |

|

Avocado |

1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Blueberry |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Mulberry |

1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Jujube |

1 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

|

Legume/tree nuts |

|

|

|

Legumes |

|

|

|

Peanut |

9 (47.4) |

3 (8.1) |

|

Soybean |

5 (26.3) |

10 (27.0) |

|

Tree nuts |

|

|

|

Chestnut |

0 (0) |

10 (27.0) |

|

Walnut |

1 (5.3) |

2 (5.4) |

|

Hazelnut |

1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Pine nut |

1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Macadamia |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Vegetables |

|

|

|

Apiaceae |

|

|

|

Carrot |

3 (15.8) |

4 (10.8) |

|

Celery |

0 (0) |

2 (5.4) |

|

Other vegetables |

|

|

|

Chinese cabbage |

1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

|

Sweet potato |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

|

Others |

|

|

|

Ginseng |

1 (5.3) |

7 (18.9) |

|

Bellflower root |

0 (0) |

2 (5.4) |

|

Burdock root |

0 (0) |

1 (2.7) |

Individual clinical manifestations of OAS were assessed by a questionnaire, which we administered by phone. The questionnaire contained items related to 1) offending foods, including fruits, known to trigger OAS symptoms, 2) local or systemic clinical manifestations of OAS, and 3) degrees of improvement in OAS and ARC symptoms following treatment. We divided degrees of improvement into five levels according to the degree of subjective reduction in symptoms: 76–100% reduction, 51–75% reduction, 26–50% reduction, 0–25% reduction, and worsening of symptoms.

The symptoms of OAS ranged from localized mucosal involvement to more severe forms with systemic organ involvement affecting the skin, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract. The questionnaire items on OAS severity consisted of eight symptoms with three weighted scales for each symptom, which was modified from the questionnaire suggested by Bergmann, et al.

10 (

Supplementary Table 1, only online). Localized symptoms were assigned 1 point, systemic symptoms with other organ involvement were assigned 2 points, and anaphylaxis was assigned 3 points. The calculated weighted OAS score was determined with the following equation:

To assess the severity of ARC, the questionnaire included three nasal symptoms (rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, sneezing) and one eye symptom (eye itching) with two grade scores (0=no, 1=yes) for each symptom.

Chi-squared and Fisher's exact test was used to compare degrees of improvement in OAS and ARC symptoms. Student's t-test was used to compare age, sIgE levels, and OAS and ARC symptom scores between the patients that received SCIT and those that did not receive SCIT. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

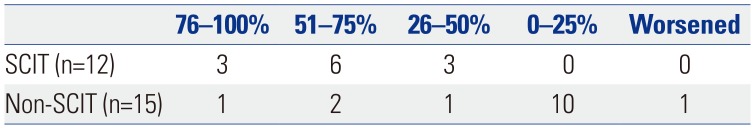

The efficacy of SCIT including Fagales pollen in patients with OAS is presented in

Table 3. Because 7 of the 19 patients that received SCIT and 24 of the 39 patients that did not receive SCIT continued to avoid culprit fruits and vegetables after treatment, only 12 and 15 patients in those groups, respectively, reported on improvement in OAS symptoms. Chi-squared analysis with Fisher's exact test showed that the patients that received SCIT had improved OAS symptoms (

p=0.005), compared with those that did not receive SCIT. Nine of the 12 patients (75%) that received SCIT reported that their OAS symptoms decreased by more than 50% after SCIT. In contrast, only three of the 15 patients (20%) that did not receive SCIT reported that their OAS symptoms decreased by 50% or more at the time of questionnaire evaluation during the follow-up. There was no difference in the duration of SCIT according to the degree of OAS improvement. None of the 19 patients that received SCIT reported any significant adverse events or worsening of OAS or ARC symptoms. Among the 37 patients that did not receive IT, one patient reported deterioration of OAS symptoms, and three patients reported that their ARC symptoms worsened.

Table 3

Improvement of Oral Allergy Syndrome Symptoms

|

76–100% |

51–75% |

26–50% |

0–25% |

Worsened |

|

SCIT (n=12) |

3 |

6 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Non-SCIT (n=15) |

1 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

1 |

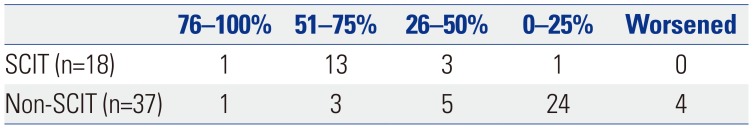

Of the 19 patients that received SCIT overall, one had a history of severe systemic reactions due to raw carrots, but that patient did not have seasonal ARC symptoms. Excluding that patient, the 18 patients that received SCIT reported that their ARC symptoms improved after SCIT (chi-squared test,

p<0.001), and 14 of those patients (77.8%) reported a greater than 50% improvement in ARC symptoms after SCIT. Only four of the 37 (10.8%) patients that did not receive IT reported that their ARC symptoms improved by more than 50% (

Table 4).

Table 4

Improvement of Allergic Rhinoconjunctivitis Symptoms

|

76–100% |

51–75% |

26–50% |

0–25% |

Worsened |

|

SCIT (n=18) |

1 |

13 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

Non-SCIT (n=37) |

1 |

3 |

5 |

24 |

4 |

The role of allergen-specific immunotherapy is a controversial issue for IgE-mediated food allergies.12 SCIT has been applied to treat IgE-mediated food allergy, but it is not recommended because of limited efficacy and a high risk of anaphylaxis. 13 Recently, oral immunotherapy for allergies to eggs, milk, and peanuts have shown good efficacy,

141516 and European guidelines recommend oral immunotherapy for food allergies only for research centers with extensive experience.

17

A few previous studies on the efficacy of SCIT for OAS treatment have reported positive results; however,

47891118 those studies used different dosages or compositions of birch pollen extracts, which might affect the efficacy of SCIT for OAS. Generally, the efficacy of SCIT for birch-apple syndrome is a controversial issue,

101920 and Mauro, et al.

4 emphasized the importance of a tailored dosage for each patient to achieve satisfactory efficacy. We used the recommended or maximum tolerable dosages to determine the maintenance doses of SCIT in our study; however, the recommended range for the maintenance dose of Bet v 1 for birch extract was quite wide (3.28–15 µg).

21 The maintenance dosage and route of administration of immunotherapy may be critical factors for the efficacy of SCIT in OAS.

2022 Our results show that SCIT with Fagales pollen-containing extracts alleviated the symptoms of OAS and ARC. About 75% of the patients that received SCIT reported that their OAS improved by more than 50%, which was significantly higher than the proportion of patients that did not receive immunotherapy who reported better than 50% improvement in their OAS symptoms. We identified one patient that had severe reactions including anaphylaxis to fresh fruits (apple, peach) and vegetables (carrot) without any ARC symptoms. That patient was sensitized with tree pollen and received immunotherapy for improvement of OAS symptoms only, not ARC symptoms. After receiving SCIT with birch and oak pollen extracts, the patient reported a 51–75% reduction in weighted OAS symptoms score. That level of efficacy was consistent with our expectations, considering the expected improvement of allergic rhinitis by SCIT. Randomized controlled studies have shown that SCIT reduced the symptoms of allergic rhinitis by 30–35% compared with placebo.

2324 Our data on the effects of SCIT on ARC symptoms were also comparable to previous results.

232425

Safety is another important concern in the use of SCIT to manage food allergies.

13 In our study, none of the 19 patients that received SCIT had significant adverse reactions. This result supports the safety and clinical feasibility of using SCIT to manage OAS.

The results of previous surveys of Korean patients with OAS with pollen sensitization are not significantly different from those of Western surveys. The frequency of OAS was higher in patients sensitized to tree pollens and lower in patients sensitized to grass pollens.

2627 Among the tree pollens, birch pollen is the most studied in terms of its relationship with OAS.

41122 In Korea, birch pollen counts in the atmosphere are not high in the spring, during which oak pollen is the major tree pollen.

2829 Oak and birch both belong to the Fagales family. This suggests that cross-allergenicity between the two pollens may be important in Korea. We already reported on significant cross-allergenicity between birch pollen and oak pollen using the sera of Korean patients with spring pollinosis, and cross-reactivity between group 1 major allergens of birch and oak pollens has been reported.

3031 The presence of unique allergens for birch pollens or oak pollens cannot be excluded, however, so we applied immunotherapy with a mixture of oak and birch pollen extracts.

Because of the diversity among different geographical settings and food cultures, different countries may have different culprit food allergens. We included patients with OAS caused by unique food materials, such as ginseng, bellflower root, and burdock root, in our study. Our results support the hypothesis that clinical features of OAS vary depending on the cultural differences in favorable food materials.

This study had several limitations because of its retrospective nature. We included only subjects who we could contact via phone calls to administer the symptom questionnaire; therefore, the participants did not necessarily represent the entire patient population. We do not know if characteristics, such as gender or age, might influence responses to the telephone questionnaire. Furthermore, the duration of immunotherapy varied from patient to patient. Some patients had completed SCIT (more than 3 years), while others were in the course of SCIT. The interval between the completion of treatment and administration of the questionnaire also varied from patient to patient, thus there might be bias due to the length of the patients' memories. We measured efficacy on the basis of the patients' subjective judgment rather than a more objective measurement by double blind placebo controlled oral food challenge test. The small number of enrolled patients that received SCIT did not provide much statistical power. A multicenter study would be required to enroll a more satisfactory number of patients. Finally, as this study is a cross-sectional study, we just showed the association of OAS improvement and SCIT, and could not prove the efficacy of SCIT on OAS. Despite these limitations, we think that more prospective randomized studies will prove that SCIT is beneficial for many patients with OAS.

Our results show that SCIT with Fagales pollens extract is associated with greater improvement in OAS symptoms and safe treatment for OAS. As OAS is the most common subtype of food allergy in adults, we believe that SCIT can play a substantial role in the treatment of adult food allergies.