Abstract

Purpose

To determine the appropriate regimen of antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in patients receiving percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL).

Materials and Methods

Forty patients, who planned to undergo PCNL from October 2015 to August 2017, were assigned randomly into two groups. Patients in the single-dose group (n=20) were administered an intravenous single dose of 2 g ceftriaxone 30 minutes before PCNL, whereas those in the three-days regimen group (n=20) were administered a preoperative intravenous single dose of 2 g ceftriaxone and an additional postoperative oral cefpodoxime proxetil (100 mg twice a day) for three days. The incidences of infectious complications in the two groups, such as pyrexia, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), and sepsis, were compared.

Results

Fever (axillary temperature >38.0℃) did not develop in any of the patients in the single-dose group but developed in one patient (5.0%) in the three-day regimen group due to pneumonia (p=0.3). SIRS developed in a total of eight patients (20.0%), four patients from each group. None of the patients in either group developed sepsis after PCNL.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is an ideal treatment for renal stones, particularly in patients with a heavy stone burden, with stone-free rates exceeding 90% [1]. The postoperative complications of PCNL include bleeding, infection, urine leakage, and residual pain [2]. Among them, bacterial infection is a frequent complication, occurring in 25% of patients who undergo PCNL. The signs of infections, including fever (21–74%), transient bacteremia (20–35%), systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS; 23.4–29.0%), and bacteriuria (10–37%), are reported more commonly [3].

In this regard, antibiotic prophylaxis before PCNL is important to prevent infections. On the other hand, the ideal prophylactic antibiotic regimen, including the duration for PCNL, has not been determined. Different regimens have been suggested by the European Association of Urology (second- or third-generation cephalosporin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, fluoroquinolones, and aminopenicillin/beta-lactamase inhibitors) and the American Urological Association (AUA) (first- or second-generation cephalosporin, ampicillin/sulbactam, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycoside plus metronidazole or clindamycin) guidelines [4].

This study examined the appropriate regimen of antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in patients receiving PCNL. The efficacy of the single-dose and three-day prophylactic antibiotic regimens for PCNL were compared prospectively.

A total of 58 adult patients who planned to undergo PCNL for renal calculi between October 2015 and August 2017 were screened. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) significant preoperative bacteriuria or a positive urine culture, 2) indwelling catheter, 3) previous antibiotic use within 2 weeks of the operation, 4) prior history of infectious stones, 5) allergy to antibiotics, and 6) refusal to enroll in the study. The patients were assigned randomly to a single-dose group or a three-day regimen group. Computer-generated random numbers were used for randomization. All the procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center (IRB no. 2015-1057) and informed consent was obtained from all patients on the day they were hospitalized for surgery. The patients were dropped from the study if postoperative complications occurred, such as bleeding, pneumothorax, or hydrothorax.

Patients in the single-dose group were administered a single dose of intravenous 2 g ceftriaxone 30 minutes before the PCNL. Patients in the three-day regimen group were administered preoperatively intravenous 2 g ceftriaxone and additional oral cefpodoxime proxetil (100 mg twice a day) for three days.

All patients underwent laboratory tests, including a complete blood count (CBC), blood chemistry, blood electrolytes, urinalysis, and midstream urine culture prior to surgery. The stone burden was measured using the longest stone diameter on the preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan. During PCNL, pelvic urine samples and fragmented renal stones were obtained for culturing. The vital signs of the patients were checked routinely at four-hour intervals on the operation day and at eight-hour intervals thereafter. Pyrexia was defined as the development of an axillary body temperature higher than 38.0℃. In those patients, laboratory tests, including CBC, urinalysis, blood culture, and urine culture, were performed routinely. The postoperative stone-free state was evaluated using a follow-up CT scan approximately 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. SIRS was diagnosed when a patient met at least two of the following four criteria: 1) body temperature <36℃ or >38℃, 2) heart rate >90 beats/minute, 3) respiratory rate >20 breaths/minute or pCO2 >32 mmHg, and 4) leukocyte count >12×103 cells/mm3 or <4×103 cells/mm3 [5].

All PCNLs were performed by a single surgeon (HK Park). The whole PCNL procedures of the authors' institution are described elsewhere [6]. Briefly, after general anesthesia, a retrograde pyelogram was performed at the lithotomy position for balloon catheter placement. After changing to the prone position, a percutaneous puncture was carried out using the Bull's eye technique. A serial dilation of the puncture tract was made to insert a 27 Fr. nephroscope. Lithoclast was used for stone fragmentation and stone was retrieved with stone forceps. A nephrostomy catheter, ureteral stent, and 4 Fr. Foley catheter were placed after the operation. Both the ureteral catheter and 14 Fr. Foley catheters were removed one day after surgery. The nephrostomy catheter was kept in place for at least 48 hours and was removed after the identification of antegrade pyelography. The ureteral stents were maintained for 1 to 2 weeks and removed at the outpatient clinic.

Of the 58 patients, 15 patients were excluded during the screening phase (Fig. 1). Seven patients had significant bacteriuria in the preoperative urine culture: Escherichia coli (n=3) was the most commonly isolated microorganism followed by Proteus mirabilis (n=2). One patient had an E. coli strain resistant to ciprofloxacin (Table 1). Therefore, 43 patients were assigned randomly. Among them, three patients were excluded due to bleeding (n=2) and a hydrothorax (n=1; Fig. 1).

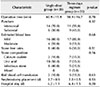

In the study population (n=40), 32 patients were male and eight were female. The mean age±standard deviation was 55.3±10.5 years. No significant differences in the baseline characteristics, including gender, age, body mass index, laterality, stone size, white blood cell count, and C-reactive protein level, were observed between the two groups (p range: 0.11–0.72; Table 2). Moreover, there were no significant differences in the intraoperative and postoperative findings (Table 3).

Fever (axillary temperature >38.0℃) did not develop in the single-dose group, but there was one case of fever (5.0%) in the three-day regimen group with a negative blood culture (p=0.3; Table 4). No bacteriuria of the renal pelvic urine was observed in both groups. One positive stone culture (5.0%) was found in the three-day regimen group but there was no significant difference between the two groups (p=0.8). The specific pathogen colonizing the stone was P. mirabilis. SIRS developed in eight patients (20.0%), four in each group. The prevalence of infection-related events was similar in the two groups.

The mechanisms for the urinary tract infection after PCNL include the release of colonizing bacteria by the surgeon's manipulations, fragmentation of the infected renal stones, and the spread of bacteria through the nephrostomy tract. Progression to sepsis following the post-PCNL SIRS is a rare [3] but life-threating condition [5]. Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to PCNL is strongly recommended because PCNL without antibiotic prophylaxis commonly causes bacteriuria (35%), post-procedural fever (10%), and sepsis (1%) [7].

Various studies have reported a number of pathogens in PCNL complications as well as their sensitivity to antibiotics. E. coli and other microorg anisms, such as Proteus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Pseudomonas species are commonly isolated in patients with PCNL [8]. In 2003, the antibiotic sensitivity rates of E. coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis were reported to be 98%, 94%, 89%, and 87%, respectively [9]. On the other hand, the acquisition of resistance to routinely prescribed antibiotics in primary-care patients with urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is increasing [10], and the resistance rates of bacteria to different antibiotics have been reported as follows: nalidixic acid (77.7%), quinolones (74.5%), gentamicin (58.2%), beta-lactamase inhibitor (57.4%), cefuroxime (56%), cotrimoxazole (48.5%), and amikacin (33.4%) [11].

The prevalence of antibiotic resistance in gram-negative pathogens differs worldwide, which suggests that the frequency of antibiotic resistance in Asia is relatively higher than that in Western countries [12]. Edlin et al. [13] analyzed 25,418 urinary isolates and reported that the resistance to first- and second-generation cephalosporins (cephalothin, cefazolin, or cefuroxime) was higher than that to third-generation cephalosporins. Therefore, third-generation cephalosporins are currently recommended as a prophylactic agent for PCNL.

The appropriate prophylactic regimen of third-generation cephalosporins for PCNL has not been determined. The recent AUA best-practice statement recommends 24 hours or less of antibiotic prophylaxis before percutaneous renal surgery in all patients had no evidence of infection [4].

One prospective study reported that an extended duration of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, even without a negative preoperative urine culture, could decrease the risk of infectious complications postoperatively. Nitrofurantoin given orally for one week before PCNL was effective in preventing urosepsis and endotoxemia in patients with a large stone burden and hydronephrosis [14]. On the other hand, the majority of studies found no difference in efficacy between single-dose prophylaxis and an additional short course of antibiotics [151617]. Recently, a randomized controlled trial reported that the use of prophylactic oral antibiotics for 7 days before surgery in low-risk patients had no added effect on the postoperative infection rates compared to the use of intravenous antibiotics for one day before surgery [18]. The results are in agreement with previous studies and demonstrate the efficacy of single-dose antibiotic prophylaxis. In addition, up to 30% of the E. coli isolates were reported to be resistant to ciprofloxacin, which correlates with the present study (33%). Overall, reducing the overuse of antibiotics is important considering the high incidence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli [19].

This was a prospective, randomized controlled trial of a single institute that included patients with a negative preoperative urine culture. The efficacy of the additional use of oral antibiotics until catheter removal and a single dose of intravenous antibiotics were compared. On the other hand, the main limitation of this study was that it was conducted at a single institution with a small number of patients. Further studies with more patients will be needed.

The additional postoperative three-day antibiotic regimen was not superior to the single-dose prophylaxis with regard to the incidence of postoperative fever and SIRS in patients undergoing PCNL for renal stones. Therefore, single-dose prophylaxis may be sufficient for patients undergoing PCNL without preoperative bacteriuria.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Turk C, Petrik A, Sarica K, Seitz C, Skolarikos A, Straub M, et al. EAU guidelines on interventional treatment for urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 2016; 69:475–482.

2. Tyson MD 2nd, Humphreys MR. Postoperative complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a contemporary analysis by insurance status in the United States. J Endourol. 2014; 28:291–297.

3. Singh P, Yadav S, Singh A, Saini AK, Kumar R, Seth A, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome following percutaneous nephrolithotomy: assessment of risk factors and their impact on patient outcomes. Urol Int. 2016; 96:207–211.

4. Wolf JS Jr, Bennett CJ, Dmochowski RR, Hollenbeck BK, Pearle MS, Schaeffer AJ. Urologic Surgery Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Best Practice Policy Panel. Best practice policy statement on urologic surgery antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol. 2008; 179:1379–1390.

5. Cadeddu JA, Chen R, Bishoff J, Micali S, Kumar A, Moore RG, et al. Clinical significance of fever after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urology. 1998; 52:48–50.

6. Shim M, Park M, Park HK. Effects of continuous peritubal local anesthetic instillation on postoperative pain after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a prospective, randomized three-arm study. J Endourol. 2016; 30:504–509.

7. Tom WR, Wollin DA, Jiang R, Radvak D, Simmons WN, Preminger GM, et al. Next-generation single-use ureteroscopes: an in vitro comparison. J Endourol. 2017; 31:1301–1306.

9. Farrell DJ, Morrissey I, De Rubeis D, Robbins M, Felmingham D. A UK multicentre study of the antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial pathogens causing urinary tract infection. J Infect. 2003; 46:94–100.

10. Bryce A, Hay AD, Lane IF, Thornton HV, Wootton M, Costelloe C. Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in paediatric urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli and association with routine use of antibiotics in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016; 352:i939.

11. Niranjan V, Malini A. Antimicrobial resistance pattern in Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infection among inpatients. Indian J Med Res. 2014; 139:945–948.

12. Zowawi HM, Harris PN, Roberts MJ, Tambyah PA, Schembri MA, Pezzani MD, et al. The emerging threat of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in urology. Nat Rev Urol. 2015; 12:570–584.

13. Edlin RS, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL, Copp HL. Antibiotic resistance patterns of outpatient pediatric urinary tract infections. J Urol. 2013; 190:222–227.

14. Bag S, Kumar S, Taneja N, Sharma V, Mandal AK, Singh SK. One week of nitrofurantoin before percutaneous nephrolithotomy significantly reduces upper tract infection and urosepsis: a prospective controlled study. Urology. 2011; 77:45–49.

15. Demirtas A, Yildirim YE, Sofikerim M, Kaya EG, Akinsal EC, Tombul ST, et al. Comparison of infection and urosepsis rates of ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone prophylaxis before percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a prospective and randomised study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012; 2012:916381.

16. Dogan HS, Sahin A, Cetinkaya Y, Akdogan B, Ozden E, Kendi S. Antibiotic prophylaxis in percutaneous nephrolithotomy: prospective study in 81 patients. J Endourol. 2002; 16:649–653.

17. Lai WS, Assimos D. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Rev Urol. 2016; 18:10–14.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download