Abstract

Background and Purpose

Although depression is a common psychiatric symptom in Alzheimer's disease (AD), there has not been a lot of research on neuropsychological characteristics of this symptom. To determine the characteristic neuropsychological deficit in patients with depression compared to patients without depression, this study compared each neuropsychological test between AD patients with depression and without depression.

Methods

Psychotropic-naïve (drug-naïve) early stage [Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR)=0.5 or CDR=1] probable AD patients with depression (n=77) and without depression (n=179) were assessed with the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery, which includes measures of memory, intelligence, and executive functioning.

Results

AD patients with depression had lower scores on the digit forward, digit backward, calculation, and Color Word Stroop Test tests compared to AD patients without depression.

Conclusion

Our study showed that AD patients with depression have disproportionate cognitive deficit, suggesting frontal (especially in the left dorsolateral), left hemisphere and left parietal dysfunction. Considering the neuropsychological differences between AD patients with depression and without depression, depression may have specific anatomic substrates.

Although Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by impairment in memory, language, visuospatial function, and executive function, various accompanying neuropsychiatric symptoms are also the important aspects of this disease. Among them, depression is one of the most common psychiatric complications of AD, with 30% to 50% prevalence. In AD, depression often has different clinical manifestations when compared with early-life depression. While classical symptoms of early-life depression such as sad mood, guilt feelings, and self-depreciation are less prominent, nonspecific inner feelings, such as lack of pleasure or not feeling well, may be the primary manifestations of depression in patients with AD. What causes these differences is not yet clear. Cognition is especially primarily and persistently affected during disease progression in AD; hence, the atypical symptomatology of AD may be attributed to this impairment.

Even in cognitively normal younger or older adults, depression may be associated with cognitive impairments.12 Although the results of studies are somewhat mixed, slowed mental processing and deficits in attention and executive function seem to be more common in depressed individuals than in non-depressed individuals in the absence of dementia. Individuals with late-onset depression have more significant cognitive impairment.3 In AD, the relationship between cognitive impairment and depression remains controversial. Some previous studies have reported the negative impact of depression on general cognition,4 measures of dementia severity, working memory, processing speed,5 attention, motor functioning, visuospatial perception and construction.6 Other investigators have found no cognitive differences between AD patients with and without depressive symptoms.7 Due to this lack of a consistent relationship or a weak relationship between cognitive abnormalities and depression, it is uncertain whether depression is secondary to cognitive impairment or epiphenomena of AD.

These inconsistent results may be due to diverse study designs, and among these confounding factors, the inclusion of patients receiving psychoactive medications in the study may be critical. Depression is not only affected by antidepressants, but also by other psychoactive medications. Due to the longstanding Korean tradition of caring for dementia patients by family members, there are a considerable number of patients with mild to moderate AD who visit dementia clinics with never been on medication status. Therefore, we can build databases for drug-naïve probable AD patients, which will thus overcome this limitation.

However, we do not know much about whether depression in AD patients is associated with impaired cognitive performance beyond the effect of dementia itself. That is, if dementia severity was held constant, would AD patients with depression perform more poorly than AD patients without depression? In this study, we used the information about the stage of dementia to group people with a similar degree of dementia severity, and examined their performance on several specific neuropsychological tests. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether diagnosed depression or reports of depressive features in AD patients were associated with additional cognitive impairment, particularly on timed tasks or tasks requiring effortful attention.

We conducted a retrospective review of 1426 patients with dementia from March 2003 to December 2015 at the Hyoja Geriatric Hospital and Seoul Veterans Hospital, using the Dementia Registry which records all clinical, laboratory, and radiological information. Among the 1426 patients with dementia, the subjects of this study included 256 patients with probable mild AD [Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) 0.5 or 1], who were newly diagnosed and not medicated before visiting hospital. All patients included in this study met the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria for probable AD.8 The patients were drug-naïve, except for episodic hypnotics that were taken for sleep disturbances. Patients who were taking psychoactive drugs, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants and cholinesterase inhibitors, were excluded from this study.

The diagnostic evaluation included the medical history, physical and neurological examination, comprehensive neuropsychological test, routine laboratory test, and brain magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans. The age at the onset of dementia was defined as the time of onset of memory disturbances that exceeded episodic forgetfulness.

A structured interview and neuropsychological examination were performed for each subject. First, in order to assess cognitive function, the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE)9 and CDR10 were used. The Barthel index11 for evaluation of activities of daily living was adopted. Secondly, Geriatric Depression Scale 15 (GDS15) was administered by a trained neuropsychologist.

The GDS is a reliable screening tool for depressive symptoms in elderly persons and patients with mild cognitive impairment. Although the usefulness of the GDS in patients with dementia, such as AD, is questionable,12 a recent study showed good consistency and reliability in AD (mostly mild stage).13 The provided cutoff screening criterion for the Korean version GDS15 for depression is 8 or more endorsed items14 and depression is defined by this score.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Veterans Health Service Medical Center.

All study subjects underwent the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery (SNSB),15 a neuropsychological test battery that includes validated and standardized tests of various cognitive areas. The SNSB includes tests that assess attention, language, praxis, calculation, visuo-constructive function, memory (verbal and visual), and frontal/executive function, and provide numeric scores in most items. Among them, digit span (forward and backward), calculation, ideomotor praxis, the Korean version of the Boston Naming Test, the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT), the Seoul Verbal Learning Test (immediate and a 20-min delayed recall trial for the 12 items), fist edge arm test, alternating hand movement test, alternating square test, Luria test, contrasting program test, go-no-go test, test of semantic fluency and letter-phonemic fluency (the Controlled Oral Word Association Test), and Stroop test (Color Word Stroop Test) were adopted for this research. All study subjects underwent neuropsychological tests using the same protocol.

The baseline characteristics and neuropsychological differences between AD patients with depression and without depression were assessed by independent t-test. For categorical variables, chi-square test was used.

Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and a significance level of 0.05 was set for analyses.

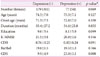

The present study included 99 men (38.7%) and 157 women (61.3%). Depression was present in 77 patients (30.1%), whereas the remaining 179 patients (69.9%) were classified as having no depression. The CDR, K-MMSE, Barthel index, GDS15, and demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without depression are presented in Table 1.

Table 2 shows the differences in each neuropsychological test between AD patients with depression and without depression. AD patients with depression showed significantly lower scores on the digit forward, digit backward, calculation, CWST word, CWST color tests compared to AD patients without depression. RCFT copy score was lower in AD patients with depression compared to AD patients without depression, although statistical significance was not reached (p=0.076).

In Table 3, the correlation between GDS15 and specific cognitive function tests in AD patients with depression is summarized. GDS15 was significantly correlated with digit forward, digit backward, calculation, CWST word, and CWST color tests.

Cognitive impairment not only changes how we perceive ourselves and the world around us, it also changes the way we feel. Previous studies in patients with early-onset depression have focused on cognitive processes and the content of depressive cognition in an attempt to understand depression. Negative views of the self, the world, and the future, as well as recurrent and uncontrollable negative thoughts are debilitating symptoms of depression. Moreover, biases in cognitive processes such as attention and memory may not only be correlates of depressive episodes; they may also play a critical role in increasing an individual's vulnerability for depression.

Three important mechanisms have been postulated as potential links between biased attentional/memory processes and emotion dysregulation in early-onset depression. However, the true pattern of cognitive impairment in patients with early-onset depression remains a matter of controversy because most studies are modest or small in terms of their sample size, and hence cognitive deficits tend to differ between and within studies, in both their nature and severity.12

The cognitive implications of depression in patients with AD have been less studied compared to those of early-onset depression. Previous studies provide evidence for both a negative relation and no significant relation of depression with cognition. These inconsistencies in results of previous studies were mainly attributable to the study subjects (medicated vs. nonmedicated, or homogeneous AD group vs. heterogeneous dementia group). Fortunately, we could overcome these limitations due to the aforementioned reasons.

In our study, AD patients with depression showed significantly lower scores on the digit forward, digit backward, calculation, and CWST tests compared to AD patients without depression. The digit span subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale comprises two tests, digits forward and backward. Digits forward is the simpler and less effortful condition requiring the efficiency of attention rather than memory.16 It tends to be more susceptible to the left hemisphere impairment rather than either the right hemisphere impairment or diffuse brain damage.17 Whereas digits backward is the more complex and effortful condition requiring executive abilities,18 which is supported by the factor analytic study loaded digit backward onto a "frontal factor".19 In addition, in neuroimaging studies among healthy adults, doing digits backward has been associated with greater frontal activation than doing digits forward.20 Accordingly, digits backward is regarded as a better test for assessing executive aspects of working memory.21 However, it should be noted that the manipulation of information during working memory tasks such as digits backward also requires activation of posterior brain regions (e.g., the superior and inferior parietal cortex, the superior temporal cortex), suggesting a role for non-frontal brain regions as well.22 Impairment of performance on calculation tests was reported in patients with a left parietal lesion.23

The ability to restrain irrelevant information, suppress activation of an inappropriate response triggered by associated cues; thus focusing on relevant information is the one of the important roles of executive functioning.24 This cognitive inhibition is an essential part of goal-directed behavior, and thus a part of maintaining daily functioning. To measure this cognitive inhibition, Stroop test is widely used. The Stroop task presents incongruously colored ink (e.g., the word 'red' printed in blue ink). Participants are asked to name the ink color of each word, while attempting to ignore the meaning of the word. This attempt to suppress word meaning in order to name ink color has led to longer response latencies than those that result from color naming congruent stimuli (e.g., the word 'red' printed in red ink), a phenomenon that has been referred to as the Stroop effect. In the first neuropsychological study with the Stroop test in patients with focal brain lesions, impairment of performance on the Stroop test was associated with a left dorsolateral prefrontal lesion.25 Another study showed that patients with left dorsolateral lesions showed impaired performance on the Stroop test.26 Moreover, superior medial lesions, particularly involving the right supplementary motor area, were also reported to be associated with errors during the interference condition of the Stroop task.27

Considering the impairment of performance on the digit forward, backward, calculation and CWST tests, our study suggested that the frontal, left hemisphere and the left parietal dysfunctions were associated with depression. In studies of major depression without dementia, the medial prefrontal areas such as the anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and also the dorsolateral prefrontal regions, ventral striatum (caudate and putamen), middle temporal regions and limbic structures are the suggested candidates for affective regulation areas. For detailed anatomical localization, neuropsy-chological tests are of limited value, but our study suggested similar anatomic areas.2428

Correlation analysis between GDS15 and specific cognitive neuropsychological tests showed a significant correlation with these neurocognitive tests. These findings imply that these specific cognitive neuropsychological tests might be not only a trait marker, but also a state marker. A trait marker shows the properties of a certain symptom that plays the role of an antecedent and possibly plays a causative role in the pathophysiology of the symptom, whereas a state marker indicates the status of clinical manifestations in patients. Although it is not possible to elucidate the cognitive impairments that cause depression or epiphenomenon, certain pathophysiological anatomy may be involved in the depressive symptomatology of AD.

However, this study had several limitations. First, this study is a retrospective study and sample size is relatively small. Secondly, depression was defined with the GDS15, a questionnaire that reflects only the patient's subjective symptoms based on the questions asked by the examiner. AD patients frequently deny having depressive symptoms. Therefore, the assessment of depression based on patient self-reports could lead to biased outcomes. Finally, our study is a hospital-based study, and hence, it may not represent the real community.

In conclusion, our study shows that AD patients with depression have a disproportionate cognitive deficit, suggesting frontal (especially in the left dorsolateral), left hemisphere and left parietal dysfunction. Considering the neuropsychological differences between AD patients with depression and without depression, depressive symptoms may have specific anatomic substrates. In a future study, a higher number of drug-naïve patients and more specific tests that represent specific anatomical substrates may provide a better understanding of the biological pathophysiology of depression in patients with AD.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Demographic data of drug-naïve AD patients with depression and without depression (mean±standard deviation)

Table 2

A comparison of neuropsychological tests between AD patients without depression and with depression

Table 3

Correlation between GDS15 and specific neuropsycological tests in AD patients with depression

*Pearson bivariate correlation was performed.

AD: Alzheimer's disease, COWAT: Controlled Oral Word Association Test, CWST: Color Word Stroop Test, GDS15: Geriatric Depression Scale 15, K-BNT: Korean version of the Boston Naming Test, RCFT: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, SVLT: Seoul Verbal Learning Test.

References

1. Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005; 1:167–195.

2. Rose EJ, Ebmeier KP. Pattern of impaired working memory during major depression. J Affect Disord. 2006; 90:149–161.

3. van Reekum R, Simard M, Clarke D, Binns MA, Conn D. Late-life depression as a possible predictor of dementia: cross-sectional and short-term follow-up results. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999; 7:151–159.

4. Rovner BW, Broadhead J, Spencer M, Carson K, Folstein MF. Depression and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1989; 146:350–353.

5. Rubin EH, Kinscherf DA, Grant EA, Storandt M. The influence of major depression on clinical and psychometric assessment of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Am J Psychiatry. 1991; 148:1164–1171.

6. Wefel JS, Hoyt BD, Massma PJ. Neuropsychological functioning in depressed versus nondepressed participants with Alzheimer's disease. Clin Neuropsychol. 1999; 13:249–257.

7. Lopez OL, Boller F, Becker JT, Miller M, Reynolds CF 3rd. Alzheimer's disease and depression: neuropsychological impairment and progression of the illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1990; 147:855–860.

8. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984; 34:939–944.

9. Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997; 15:300–308.

10. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982; 140:566–572.

11. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965; 14:61–65.

12. Debruyne H, Van Buggenhout M, Le Bastard N, Aries M, Audenaert K, De Deyn PP, et al. Is the geriatric depression scale a reliable screening tool for depressive symptoms in elderly patients with cognitive impairment? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009; 24:556–562.

13. Kwak YT, Song SH, Yang Y. The Relationship between Geriatric Depression Scale structure and cognitive-behavioral aspects in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Neurocognitive Disord. 2015; 14:24–30.

14. Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 57:297–305.

15. Kang Y, Na DL. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery (SNSB). 1st ed. Incheon: Human Brain Research & Consulting Co.;2003.

16. Kaufman AS, McLean JE, Reynolds CR. Analysis of WAIS-R factor patterns by sex and race. J Clin Psychol. 1991; 47:548–557.

17. Hom J, Reitan RM. Neuropsychological correlates of rapidly vs. slowly growing intrinsic cerebral neoplasms. J Clin Neuropsychol. 1984; 6:309–324.

18. Butters N, Delis DC, Lucas JA. Clinical assessment of memory disorders in amnesia and dementia. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995; 46:493–523.

19. Glisky EL, Polster MR, Routhieaux BC. Double dissociation between item and source memory. Neuropsychol. 1995; 9:229–235.

20. Gerton BK, Brown TT, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kohn P, Holt JL, Olsen RK, et al. Shared and distinct neurophysiological components of the digits forward and backward tasks as revealed by functional neuroimaging. Neuropsychologia. 2004; 42:1781–1787.

21. Phillips LH. Do "frontal tests" measure executive function? Issues of assessment and evidence from fluency tests. In : Rabbit P, editor. Methodology of Frontal and Executive Function. Hove: Psychology Press;1997. p. 191–213.

22. Collette F, Van der Linden M. Brain imaging of the central executive component of working memory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002; 26:105–125.

23. Bench CJ, Frith CD, Grasby PM, Friston KJ, Paulesu E, Frackowiak RS, et al. Investigations of the functional anatomy of attention using the Stroop test. Neuropsychologia. 1993; 31:907–922.

24. Wise T, Cleare AJ, Herane A, Young AH, Arnone D. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of neuroimaging in depression: an overview. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014; 10:1509–1522.

25. Perret E. The left frontal lobe of man and the suppression of habitual responses in verbal categorical behaviour. Neuropsychologia. 1974; 12:323–330.

26. Stuss DT, Floden D, Alexander MP, Levine B, Katz D. Stroop performance in focal lesion patients: dissociation of processes and frontal lobe lesion location. Neuropsychologia. 2001; 39:771–786.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download