This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background and Purpose

The recent successes of the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials have extended the therapeutic time window for endovascular treatment (EVT). Accordingly, an increased care burden and clinical benefit for patients with acute stroke in the emergency room are expected. It is necessary to evaluate and respond to these changes in order to provide the best care to patients.

Methods

Data of patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack treated at Seoul National University Hospital between October 2010 and September 2016 were reviewed. To estimate the increased workload associated with the revised guidelines, clinical candidates of acute stroke based on the initial history and examination findings and eligible patients for early stroke intervention were selected. Additionally, the data of eligible patients who received EVT more than 6 hours after the onset were reviewed.

Results

The serial addition of intravenous thrombolysis, EVT within 6 hours, and EVT beyond 6 hours to the guidelines resulted in 506 (19.8%), 588 (23.0%), and 718 (28.0%) clinical candidates, respectively, and 329 (12.8%), 365 (14.3%), and 389 (15.2%) eligible patients out of 2,561 patients with stroke. Compared to applying the previous stroke guidelines, the number of clinical candidates increased by 130 (22.1%), whereas the number of eligible patients for early stroke intervention increased by only 24 (6.6%). Seven of the 24 eligible patients received off-label EVT and showed significantly improved neurological outcomes at discharge.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the small number of subjects in this study, providing EVT to eligible patients beyond 6 hours may improve their neurological outcomes.

Go to :

Keywords: stroke, endovascular procedures, thrombectomy, emergency medical services, healthcare costs

INTRODUCTION

The paradigm for the early management of acute ischemic stroke is changing rapidly. Intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) has emerged as a powerful treatment option for ischemic stroke patients within 4.5 hours of the onset.

12 However, the number of patients with acute stroke that benefitted from intravenous rtPA was not much higher than expected, owing to the narrow time window, the presence of contraindications, and the relatively low recanalization rate for large-artery occlusion.

3 The development of stent-retriever devices has been another innovation in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Serial randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of endovascular treatment (EVT) using stent-retriever devices in acute ischemic stroke patients with large-artery occlusion within 6 hours of the onset.

45678910 In addition, the recent successes of the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials have extended the time window of EVT to beyond 6 hours from the onset.

1112 The Class I recommendation in the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines now includes applying EVT to selected patients with ischemic stroke presenting more than 6 hours after the last known normal (LKN) time.

13

The increasing diversity of the available options for early intervention in acute stroke is expected to increase the role of neurologists and the demand for medical resources in the emergency room. To evaluate the workload increase in the emergency room and clinical benefit with this paradigm shift in the acute stroke care, we reviewed and selected clinical candidates and eligible patients for early intervention according to the changing guidelines among patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) treated at Seoul National University Hospital between 2010 and 2016.

Go to :

METHODS

Data collection

Based on the prospective stroke registry of Seoul National University Hospital, we reviewed clinical, laboratory, and radiological information of patients diagnosed with acute stroke or TIA within 7 days from the onset between October 2010 and September 2016. The following baseline demographic and clinical data were collected: age, sex, stroke risk factors [hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, previous history of stroke, habitual smoking (current or past), and atrial fibrillation], use of antithrombotic drugs, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at admission, premorbid modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score, and LKN time. The subtype of stroke was assessed based on the findings of CT or MRI, and cases of ischemic stroke were further classified according to the Trial of ORG 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification with minor modifications. The NIHSS score at discharge was assessed by experienced neurologists, while the 3-month mRS score was documented through an outpatient clinic evaluation or telephone interview in all patients. Intravenous rtPA (Actilyse, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) was administered to patients who were eligible according to the current guideline, and EVT was performed according to the clinical guidelines and institutional protocols in effect at the time of presentation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. H-1804-027-934), which waived the need for obtaining informed consent.

Neuroimaging investigations

Between October 2010 and August 2015, patients with acute stroke or TIA diagnosed within 6 hours of the first known abnormal (FKA) time initially underwent precontrast brain CT. If no evidence of bleeding was detected, brain MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) were performed to further evaluate the need for EVT. Brain DWI and MRA scans were examined for patients diagnosed more than 6 hours after the FKA time.

Between September 2015 and September 2016, brain CT with CT angiography and CT perfusion imaging were first performed for patients within 8 hours of the FKA time. EVT was then applied if there was any indication in the CT findings. Patients with ischemic stroke not eligible for EVT were further assessed using brain MRI with DWI and MRA.

Selection of clinical candidates and eligible patients

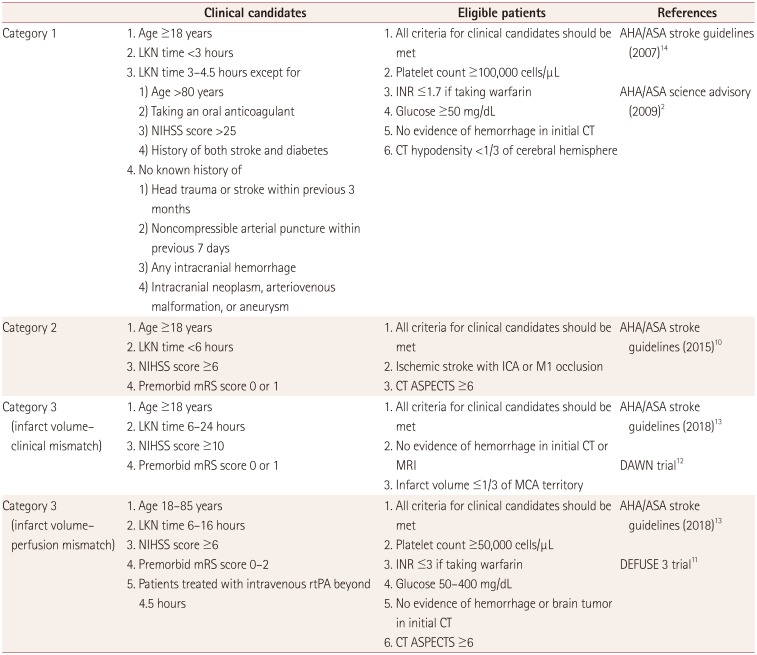

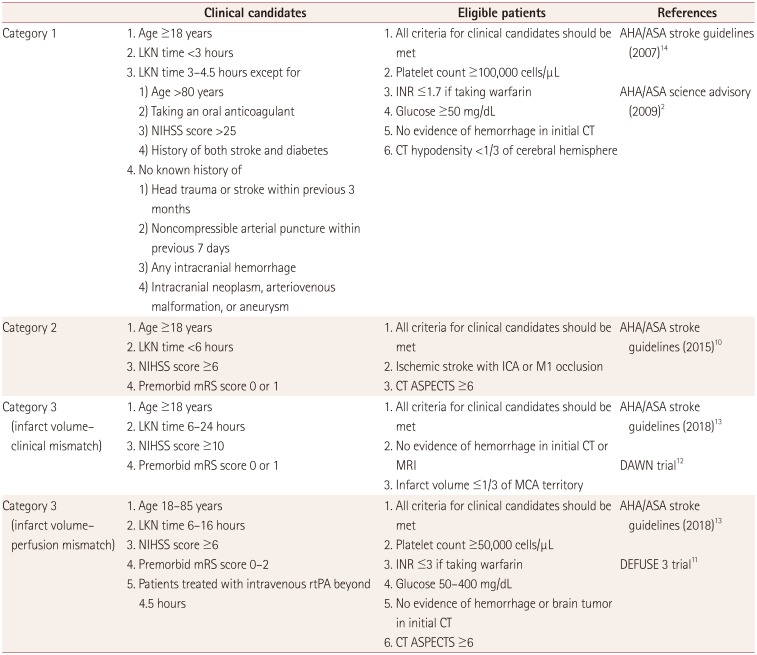

As described above, three milestones led to paradigm shifts in the early management of acute ischemic stroke: intravenous rtPA, EVT with a stent retriever within 6 hours, and EVT with a stent retriever beyond 6 hours. To estimate the changes in workload associated with the available treatment options for stroke patients, we set three categories according to these milestones: category 1, intravenous rtPA; category 2, EVT with a stent retriever within 6 hours; and category 3, EVT with a stent retriever beyond 6 hours. Clinical candidates were defined as patients who might be eligible for intravenous thrombolysis or EVT immediately after history-taking and a neurological examination. When a clinical candidate enters the emergency room, serial preparations including patient placement, assigned medical staff, and medications for intravenous rtPA or EVT should be made in case emergency treatment is required.

A critical pathway is implemented at Seoul National University Hospital for acute stroke patients who enter the emergency room. When a patient with stroke symptoms such as hemiparesis, dysarthria, or mental change within 8 hours of the FKA time enters the emergency room, a primary evaluation is performed immediately by an emergency physician. If acute stroke is still suspected in this evaluation, the emergency physician contacts the duty neurologist directly, who then promptly reassesses the patients and determines whether to perform neuroimaging and an early stroke intervention. This constitutes the beginning of an increased workload in the emergency room, and therefore the clinical candidate might be the most appropriate indicator for estimating the care burden of acute stroke in the emergency room.

Patients were defined as being eligible for EVT when laboratory and neuroimaging inclusion/exclusion criteria listed on the stroke guidelines and the institutional protocol at the milestone points were additionally applied. Clinical candidates and eligible patients were selected from among the patients with acute stroke or TIA from the stroke registry according to the criteria for each category (

Table 1).

Table 1

Criteria for selecting clinical candidates and eligible patients in each category

|

Clinical candidates |

Eligible patients |

References |

|

Category 1 |

1. Age ≥18 years |

1. All criteria for clinical candidates should be met |

AHA/ASA stroke guidelines (2007)14

|

|

2. LKN time <3 hours |

2. Platelet count ≥100,000 cells/μL |

AHA/ASA science advisory (2009)2

|

|

3. LKN time 3–4.5 hours except for |

3. INR ≤1.7 if taking warfarin |

|

|

1) Age >80 years |

4. Glucose ≥50 mg/dL |

|

|

2) Taking an oral anticoagulant |

5. No evidence of hemorrhage in initial CT |

|

|

3) NIHSS score >25 |

6. CT hypodensity <1/3 of cerebral hemisphere |

|

|

4) History of both stroke and diabetes |

|

|

|

4. No known history of |

|

|

|

1) Head trauma or stroke within previous 3 months |

|

|

|

2) Noncompressible arterial puncture within previous 7 days |

|

|

|

3) Any intracranial hemorrhage |

|

|

|

4) Intracranial neoplasm, arteriovenous malformation, or aneurysm |

|

|

|

Category 2 |

1. Age ≥18 years |

1. All criteria for clinical candidates should be met |

AHA/ASA stroke guidelines (2015)10

|

|

2. LKN time <6 hours |

2. Ischemic stroke with ICA or M1 occlusion |

|

3. NIHSS score ≥6 |

3. CT ASPECTS ≥6 |

|

4. Premorbid mRS score 0 or 1 |

|

|

Category 3 (infarct volume–clinical mismatch |

1. Age ≥18 years |

1. All criteria for clinical candidates should be met |

AHA/ASA stroke guidelines (2018)13

|

|

2. LKN time 6–24 hours |

2. No evidence of hemorrhage in initial CT or MRI |

DAWN trial12

|

|

3. NIHSS score ≥10 |

3. Infarct volume ≤1/3 of MCA territory |

|

|

4. Premorbid mRS score 0 or 1 |

|

|

|

Category 3 (infarct volume–perfusion mismatch) |

1. Age 18–85 years |

1. All criteria for clinical candidates should be met |

AHA/ASA stroke guidelines (2018)13

|

|

2. LKN time 6–16 hours |

2. Platelet count ≥50,000 cells/μL |

DEFUSE 3 trial11

|

|

3. NIHSS score ≥6 |

3. INR ≤3 if taking warfarin |

|

|

4. Premorbid mRS score 0–2 |

4. Glucose 50–400 mg/dL |

|

|

5. Patients treated with intravenous rtPA beyond 4.5 hours |

5. No evidence of hemorrhage or brain tumor in initial CT |

|

|

6. CT ASPECTS ≥6 |

|

In the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials, the mismatch between the infarct volume and the clinical deficit or perfusion was evaluated using automated RAPID software (iSchemaView,

http://www.i-rapid.com/home).

1112 Since this software is currently not widely available in clinical settings in Korea, we defined patients with an initial NIHSS score of more than 10 and an infarct volume of less than 1/3 of the middle cerebral artery territory in DWI or the cerebral blood volume (CBV) in perfusion CT as an infarct volume-clinical mismatch. Patients were considered as having an infarct volume-perfusion mismatch if a mismatch was detected by experienced neurologists between the Tmax value from PWI/CT perfusing imaging and DWI/CBV imaging.

Review of off-label EVT cases among category 3 patients

Applying EVT with the extended indication according to the results of the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials requires data from real-world patients. Before the inclusion of EVT after 6 hours as the Class I recommendation in the stroke guidelines, Seoul National University Hospital had applied off-label EVT to selected patients beyond 6 hours from the onset in the presence of a diffusion-clinical or diffusion-perfusion mismatch at the discretion of the clinicians and intervention neuroradiologists. We reviewed the data of patients who had received off-label EVT among eligible patients based on the 2018 updated recommendation for EVT beyond 6 hours. EVTs were performed by skilled intervention neuroradiologists using stent-retriever devices. Groin puncture times were collected and the modified treatment in cerebral infarction scores were assessed based on pre- and posttreatment conventional angiography images. Demographic factors, stroke risk factors, antithrombotic agent use, TOAST classification, initial and discharge NIHSS scores, and premorbid and 3-month mRS scores were obtained from the stroke registry.

Statistical methods

Baseline demographic and clinical parameters of category 3 patients depending on EVT were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or chi-square test, as appropriate. Two-sided probability values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 3.4.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Go to :

RESULTS

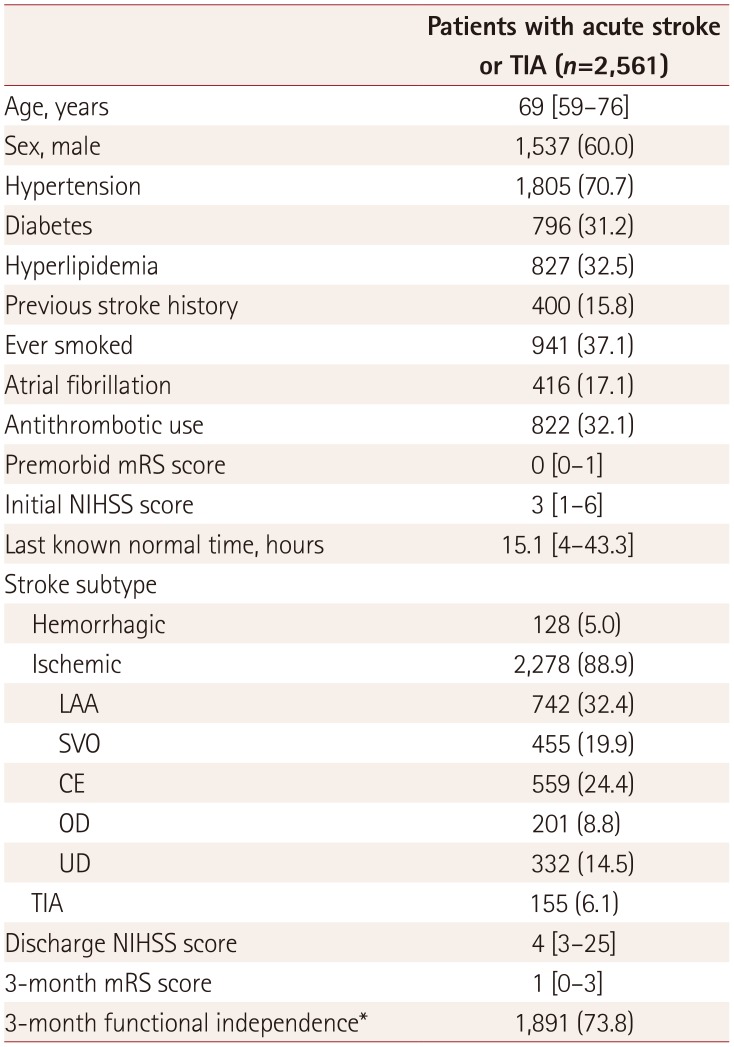

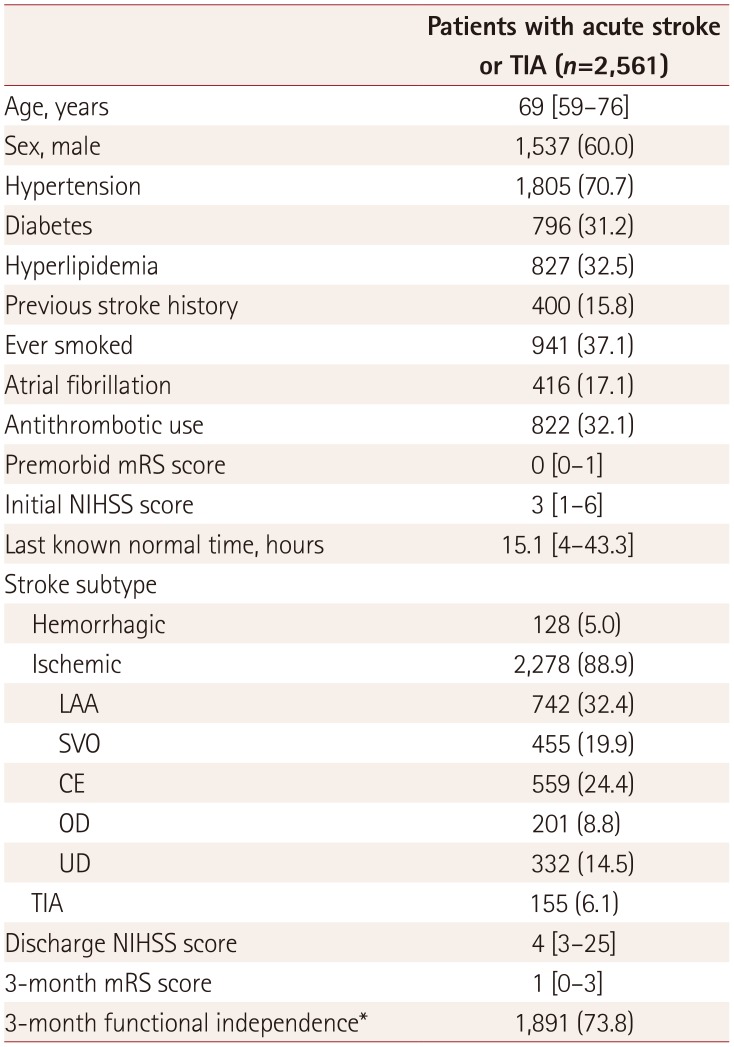

Between October 2010 and September 2016, 2,561 patients were admitted to Seoul National University Hospital with acute stroke or TIA within 7 days from the onset. Their baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes are presented in

Table 2.

Table 2

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients included in the study

|

Patients with acute stroke or TIA (n=2,561) |

|

Age, years |

69 [59–76] |

|

Sex, male |

1,537 (60.0) |

|

Hypertension |

1,805 (70.7) |

|

Diabetes |

796 (31.2) |

|

Hyperlipidemia |

827 (32.5) |

|

Previous stroke history |

400 (15.8) |

|

Ever smoked |

941 (37.1) |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

416 (17.1) |

|

Antithrombotic use |

822 (32.1) |

|

Premorbid mRS score |

0 [0–1] |

|

Initial NIHSS score |

3 [1–6] |

|

Last known normal time, hours |

15.1 [4–43.3] |

|

Stroke subtype |

|

|

Hemorrhagic |

128 (5.0) |

|

Ischemic |

2,278 (88.9) |

|

LAA |

742 (32.4) |

|

SVO |

455 (19.9) |

|

CE |

559 (24.4) |

|

OD |

201 (8.8) |

|

UD |

332 (14.5) |

|

TIA |

155 (6.1) |

|

Discharge NIHSS score |

4 [3–25] |

|

3-month mRS score |

1 [0–3] |

|

3-month functional independence*

|

1,891 (73.8) |

The number of potential target patients for early stroke intervention (i.e., intravenous rtPA or EVT) gradually increased as the guidelines changed. Of 2,561 patients with stroke, the numbers of clinical candidates for early stroke intervention set for estimating care burden were 506 (19.8%), 588 (23.0%), and 718 (28.0%) as the criteria for categories 1, 2, and 3, respectively, were serially added. The numbers of eligible patients for early stroke intervention after the initial laboratory and neuroimaging studies in the emergency room were 329 (12.8%), 365 (14.3%), and 389 (15.2%), respectively (

Fig. 1A). The new stroke guidelines announced in 2018. increased the number of clinical candidates by 130 and the number of eligible patients by 24 for early stroke intervention, which represent increases of 22.1% and 6.6% compared to the 588 and 365 patients, respectively, selected by applying the previous guidelines.

| Fig. 1The number of beneficiaries of EVT was increased and EVT beyond 6 hours from onset improved neurological outcomes of selected patients. A: Clinical candidates and eligible patients selected by the criteria for categories 1, 2, and 3; 506 (19.8%) of 2,561 patients were designated as category 1 clinical candidates, and 588 (23.0%) patients were clinical candidates who met the criteria for category 1 or 2. The number of clinical candidates satisfying at least one of the criteria for category 1, 2, or 3 was 718 (28.0%). Totals of 329 (12.8%), 365 (14.3%), and 389 (15.2%) patients were eligible according to the criteria for category 1, category 1 or 2, and category 1, 2, or 3, respectively. B: Neurological status at admission and discharge according to off-label EVT beyond 6 hours from the last known normal time. The initial deficits were similar in the two groups, but the neurological symptoms at discharge were significantly improved in those who received off-label EVT. The horizontal line inside the box represents the median, the box shows the interquartile range, and the vertical lines represent the interquartile range extended to 1.5 times. *p<0.05. EVT: endovascular treatment, IV rtPA: intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, ns: not significant.

|

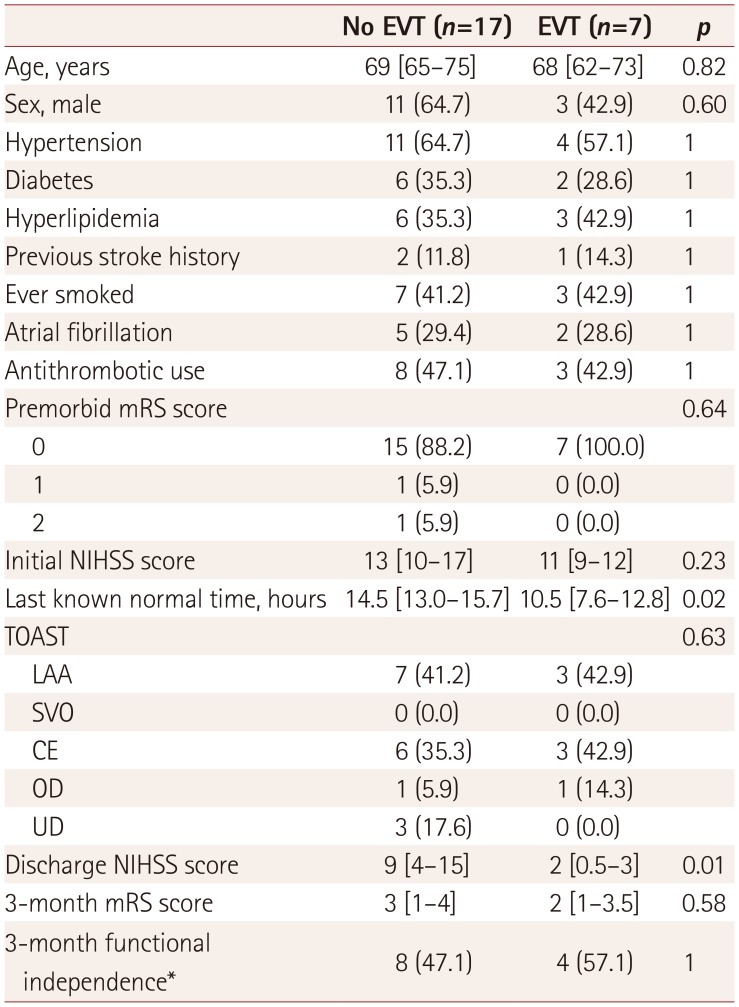

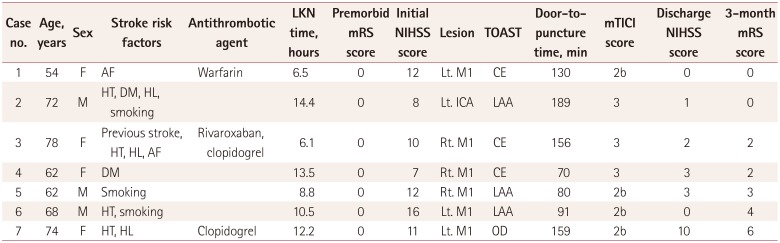

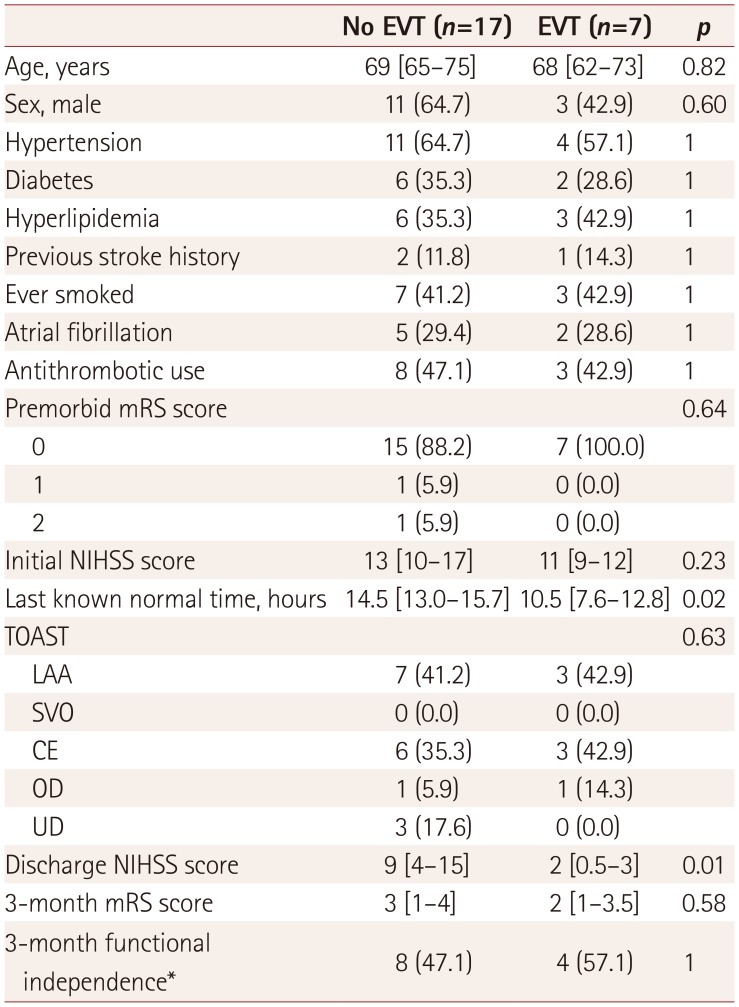

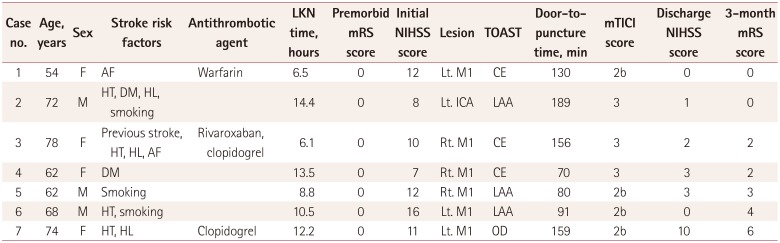

Seven of the 24 eligible category 3 patients received off-label EVT with stent-retriever devices. None of them received intravenous rtPA. No significant differences in the initial NIHSS score were detected between the EVT and non-EVT groups. However, at discharge, the NIHSS score was significantly lower in the EVT group than in the non-EVT group (

Fig. 1B,

Table 3). Baseline demographic data and pre- and posttreatment clinical information of category 3 patients who had received EVT are presented in

Table 4.

Table 3

Demographic and clinical comparison of eligible category 3 patients who received or did not receive EVT

|

No EVT (n=17) |

EVT (n=7) |

p

|

|

Age, years |

69 [65–75] |

68 [62–73] |

0.82 |

|

Sex, male |

11 (64.7) |

3 (42.9) |

0.60 |

|

Hypertension |

11 (64.7) |

4 (57.1) |

1 |

|

Diabetes |

6 (35.3) |

2 (28.6) |

1 |

|

Hyperlipidemia |

6 (35.3) |

3 (42.9) |

1 |

|

Previous stroke history |

2 (11.8) |

1 (14.3) |

1 |

|

Ever smoked |

7 (41.2) |

3 (42.9) |

1 |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

5 (29.4) |

2 (28.6) |

1 |

|

Antithrombotic use |

8 (47.1) |

3 (42.9) |

1 |

|

Premorbid mRS score |

|

|

0.64 |

|

0 |

15 (88.2) |

7 (100.0) |

|

|

1 |

1 (5.9) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

2 |

1 (5.9) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

Initial NIHSS score |

13 [10–17] |

11 [9–12] |

0.23 |

|

Last known normal time, hours |

14.5 [13.0–15.7] |

10.5 [7.6–12.8] |

0.02 |

|

TOAST |

|

|

0.63 |

|

LAA |

7 (41.2) |

3 (42.9) |

|

|

SVO |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

CE |

6 (35.3) |

3 (42.9) |

|

|

OD |

1 (5.9) |

1 (14.3) |

|

|

UD |

3 (17.6) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

Discharge NIHSS score |

9 [4–15] |

2 [0.5–3] |

0.01 |

|

3-month mRS score |

3 [1–4] |

2 [1–3.5] |

0.58 |

|

3-month functional independence*

|

8 (47.1) |

4 (57.1) |

1 |

Table 4

Summary of eligible patients who received off-label EVT beyond 6 hours from the onset before the announcement of the revised stroke guidelines

|

Case no. |

Age, years |

Sex |

Stroke risk factors |

Antithrombotic agent |

LKN time, hours |

Premorbid mRS score |

Initial NIHSS score |

Lesion |

TOAST |

Door-topuncture time, min |

mTICI score |

Discharge NIHSS score |

3-month mRS score |

|

1 |

54 |

F |

AF |

Warfarin |

6.5 |

0 |

12 |

Lt. M1 |

CE |

130 |

2b |

0 |

0 |

|

2 |

72 |

M |

HT, DM, HL, smoking |

|

14.4 |

0 |

8 |

Lt. ICA |

LAA |

189 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

3 |

78 |

F |

Previous stroke, |

Rivaroxaban, clopidogrel |

6.1 |

0 |

10 |

Rt. M1 |

CE |

156 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

4 |

62 |

F |

DM |

|

13.5 |

0 |

7 |

Rt. M1 |

CE |

70 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

|

5 |

62 |

M |

Smoking |

|

8.8 |

0 |

12 |

Rt. M1 |

LAA |

80 |

2b |

3 |

3 |

|

6 |

68 |

M |

HT, smoking |

|

10.5 |

0 |

16 |

Lt. M1 |

LAA |

91 |

2b |

0 |

4 |

|

7 |

74 |

F |

HT, HL |

Clopidogrel |

12.2 |

0 |

11 |

Lt. M1 |

OD |

159 |

2b |

10 |

6 |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The updated stroke guidelines increased the number of clinical candidates by 130 (22.1%) and the number of eligible patients by 24 (6.6%) for early stroke intervention compared to the previous guidelines. There was an appreciable increase in workload associated with the clinical candidates, whereas the increase in the eligible population was considerably smaller. Nonetheless, patients who received off-label EVT within 6–24 hours showed notably improved clinical outcomes in the present study.

The paradigm for the early management of acute stroke is changing with the rapid recent advances in EVT techniques using stent-retriever devices. Candidates for intravenous rtPA or EVT should be evaluated and treated as soon as possible in order to achieve better neurological outcomes. This means that special attention is needed when these patients are evaluated in the emergency room. Many Korean centers now operate a critical pathway for clinical candidates of acute stroke. In the present study, the number of clinical candidates who need careful investigations for early stroke intervention increased by 22.1% following the most-recent update of the stroke guidelines. Once a clinical candidate enters the emergency room, several healthcare workers (i.e., at least two emergency medicine doctors, two neurologists, one patient transporter, two nurses, and two radiological technologists in Seoul National University Hospital) should immediately become involved in the critical pathway for the patient. In addition, clinical candidates should receive emergency brain imaging to determine whether they are suitable for an early stroke intervention.

The time and cost required for these urgent neuroimaging studies are also expected to increase considerably, which might delay the application of imaging studies and appropriate treatment to patients who have been waiting in the emergency room due to diseases other than stroke. The workload for acute stroke care in the emergency room is therefore expected to increase significantly. However, the application of the new guidelines resulted in the number of actual patients eligible for early stroke intervention increasing by only 24 (6.6%). This suggests that compared to the increase in the acute stroke care burden, the additional number of beneficiaries resulting from applying the new guidelines might be modest.

Seven patients who received off-label EVT showed improved NIHSS scores at discharge, and more than half of them achieved long-term functional independence, which is similar to the rate reported for the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials. The present study provides further evidence that the recommendations of the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials can be applied to real-world eligible patients and lead to improved clinical outcomes, although the number of additional recipients for early stroke intervention might be small. Future studies should evaluate whether the improved clinical outcomes of a relatively small number of beneficiaries will outweigh the increase in workload when the time window of EVT is expanded according to the new guidelines. The staffing and financial implications of the increased workload experienced by neurologists in the emergency room also need to be determined.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, only data from a single center for Korean patients were included, and so the obtained results should be interpreted with caution when considering the system of emergency medicine and ethnicity. Second, the sample of eligible category 3 patients was small, which might have been responsible for no conclusion being drawn about whether there was difference in long-term outcome between eligible category 3 patients who received and did not receive EVT. Third, the criteria for off-label EVT were not the same as those in the 2018 stroke guidelines, since the procedures were performed prior to the announcement of the new guidelines. Moreover, off-label EVT tended to be performed in patients who came to the emergency room earlier from the onset. Accordingly, it is challenging to exclude potential selection bias when determining whether to perform off-label EVT. Finally, the infarct and penumbra volumes were not calculated by the automated RAPID software as in the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials, instead being assessed based on the judgment of clinicians based on neuroimaging findings. This might have influenced the selection of eligible category 3 patients. However, the methods used in the present study might be closer to those applied in clinical practice, because the RAPID software is not widely available.

Advances in EVT techniques are expected to increase the number of patients with stroke who are eligible for early intervention. Even if the number of eligible patients for EVT beyond 6 hours from the onset may be small, the beneficiaries of the procedure could show improved neurological outcomes. The increasing workloads of neurologists in the emergency room makes it necessary to ensure that human and financial resources are prepared accordingly. The results of the present study can be used as basic data for estimating the demand of these resources. With appropriate preparation, this new treatment technique for acute stroke could be applied in an optimal way to more patients with stroke.

Go to :

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI17 C0076), the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2015R1A2A2A01007770), and Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in Korea (IBS-R006-D1).

Go to :

Notes

Go to :

References

1. Adams HP Jr, Brott TG, Furlan AJ, Gomez CR, Grotta J, Helgason CM, et al. Guidelines for thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke: a supplement to the guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996; 94:1167–1174. PMID:

8790069.

2. Del Zoppo GJ, Saver JL, Jauch EC, Adams HP Jr. American Heart Association Stroke Council. Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: a science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009; 40:2945–2948. PMID:

19478221.

3. Bhatia R, Hill MD, Shobha N, Menon B, Bal S, Kochar P, et al. Low rates of acute recanalization with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in ischemic stroke: real-world experience and a call for action. Stroke. 2010; 41:2254–2258. PMID:

20829513.

4. Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, Van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:11–20. PMID:

25517348.

5. Bracard S, Ducrocq X, Mas JL, Soudant M, Oppenheim C, Moulin T, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy after intravenous alteplase versus alteplase alone after stroke (THRACE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016; 15:1138–1147. PMID:

27567239.

6. Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, Yassi N, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1009–1018. PMID:

25671797.

7. Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1019–1030. PMID:

25671798.

8. Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, de Miquel MA, Molina CA, Rovira A, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2296–2306. PMID:

25882510.

9. Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener HC, Levy EI, Pereira VM, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2285–2295. PMID:

25882376.

10. Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, Coffey CS, Hoh BL, Jauch EC, et al. 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association focused update of the 2013 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke regarding endovascular treatment: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015; 46:3020–3035. PMID:

26123479.

11. Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, Christensen S, Tsai JP, Ortega-Gutierrez S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:708–718. PMID:

29364767.

12. Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, Bonafe A, Budzik RF, Bhuva P, et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:11–21. PMID:

29129157.

13. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018; 49:e46–e110. PMID:

29367334.

14. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007; 38:1655–1711. PMID:

17431204.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download