Abstract

Pancreatic metastasis from cervical cancer is extremely rare. We report a case of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas from uterine cervical cancer. A 70-year-old woman was referred because of a pancreatic mass detected by CT. She had been diagnosed with uterine cervical adenocarcinoma 20 months previously. After concurrent chemoradiotherapy, CT showed no evidence of the cervical mass, and follow-up showed no evidence of recurrence. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of the pancreatic mass resulted in a diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma from uterine cervix.

Pancreatic metastasis from carcinoma of the uterine cervix is rare, and the condition has only been reported on a small number of occasions.12345 Here, we report a case of pancreatic metastasis from adenocarcinoma of the cervix confirmed by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy.

A 70-year-old woman with a prior diagnosis of uterine cervical adenocarcinoma 20 months previously was referred because of a pancreatic mass. MRI revealed a 3.4 cm sized cervical mass that had invaded posterior fornix and both parametria with suspected metastasis to bilateral internal iliac lymph nodes (stage IIB). The patient received six cycles of concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cisplatin, 54.0 Gy) and intracavitary radiotherapy (24.0 Gy) over nine weeks, and 4 months after completing treatment, follow-up CT showed no cervical mass or enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvic cavity. Eighteen months after treatment completion, abdominal CT revealed a 3.5 cm sized mass at the pancreatic body (Fig. 1), but no mass in the cervix, and as a result she was referred for further evaluation.

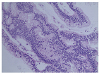

At this time the patient complained of low back pain of three weeks duration. Abdominal pain and weight loss were not obvious. Vital signs were stable, and physical examination revealed no specific abnormality. Laboratory test results were as follows: white blood count 6,300/mm3 (neutrophils 77%), mg/dL, creatinine 1.0 mg/dL, sodium 144 mmol/L, potassium 4.7 mmol/L, chloride 108 mmol/L, total protein 7.2 g/dL, albumin 4.7 g/dL, AST 29 U/L, alanine transaminase 26 U/L, ALP 97 U/L, total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dL, amylase 53 U/L, lipase 43 U/L, and CA 19-9 19.2 U/mL (normal, <37.0 U/mL). Pancreatic MRI revealed a 3.5 cm mass in the body and irregular dilation of the upstream main pancreatic duct in an atrophic pancreas tail (Fig. 2). Whole body PET/CT showed intense 18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the pancreatic mass (Fig. 3) and mild uptake in multiple tiny lung nodules. EUS showed an ill-defined hypoechoic mass in the pancreatic body. Fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed using 22-gauge needle (Procore; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) (Fig. 4), and results revealed adeno- carcinoma with atypical neoplastic glands, cellular crowding, stratification, and hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 5). Although considered pancreatic adenocarcinoma, immunohistochemical staining was performed given the history of endocervical type adenocarcinoma. The tumor was found to be positive for cytokeratin 7, p16 (Fig. 6), and caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2, which matched results for cervical cancer tissue collected by cervical biopsy 20 months previously. Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping (GeneFinder TM HPV Liquid Bead MicroArray Genotype kit; Infopia Co., Ltd., Anyang, Korea) revealed the presence of the HPV type 18 genome, which was also detected in cervical cancer tissue. The final diagnosis was pancreatic metastasis from cervical adenocarcinoma. The patient was discharged from hospital to receive treatment at another institution.

Metastatic cancer of the pancreas is rare with a reported frequency of 2–5% among all malignant pancreatic tumors.4 Renal cell carcinoma is the most common solid tumor that metastasizes to the pancreas,6 whereas pancreatic metastasis from cervical cancer is extremely rare.12345

The histopathology of cervical cancer is usually squamous cell carcinoma, but the prevalence of adenocarcinoma is increasing. Uterine cervical adenocarcinoma comprises nearly 20–25% of all cervical malignancies in developed countries, and more aggressive biological behavior has been reported in patients with intermediate and high-risk factors after surgery. Furthermore, in patients with advanced stage disease (over III), radiotherapy alone and concurrent cisplatin-based chemo-radiotherapy have been reported to be ineffective.7

In a case report of pancreatic metastasis from cervical adenocarcinoma in a 57-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIA adenocarcinoma of cervix,8 PET/CT revealed focal pancreatic uptake, and EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of the pancreatic lesion revealed adenocarcinoma matching the histopathologic findings of the lesion at the primary site. To the best of our knowledge, the described case is only the second reported case of pancreatic metastasis from cervical adenocarcinoma.

Pancreatic metastasis has been diagnosed based on the findings of imaging modalities such as ultrasonography, EUS, CT, MRI, or PET, and the recent increased usage of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration has made it possible to achieve histopathological diagnoses. Differentiating primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer is not straightforward. In CT images, primary pancreatic cancer and metastatic cancer have similar enhancement patterns, except for metastatic cancer from renal cell carcinoma. In a recent study, it was observed that pancreatic metastasis showed persistent low attenuation in 75% of cases in non-renal cell carcinoma by multidetector-row CT.9 In the described case, we concluded pancreatic metastasis originated from cervical cancer because the patient had a history of cervical adenocarcinoma, which had been diagnosed 20 months previously and because the HPV type 18 genome was detected in pancreatic and cervical specimens. Furthermore, immunostaining results for pancreatic and cervical tumor specimens for CK7, p16 and CDX2 were identical. Primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer are known to express CK7 and CDX2, although in previous studies only a minority of cases exhibited CDX2 positivity.1011 Therefore, immunohistochemical results for CK7 and CDX2 are not sufficient to differentiate these tumors. Diffuse positive immunostaining for p16 is a good surrogate marker of high-risk HPV infection in uterine cervical cancer.12 However, it has been reported diffuse positive staining for p16 is also possible in pancreatic cancer,13 and thus, p16 positivity does not in itself indicate metastatic cervical cancer. Accordingly, we performed HPV genotyping. Type 18 is the second-most common HPV after type 16 in cervical adenocarcinoma and is more specific for adenocarcinoma than squamous cell carcinoma.14 High-risk HPV genomes have not been reported in primary pancreatic cancer except in one study, in which HPV type 16 was detected in a patient with a borderline pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm.15 Accordingly, confirmation of the presence of high-risk HPV genomes is important for determining whether a pancreatic tumor has metastasized from HPV-associated primary cancer elsewhere in the body, such as the uterine cervix. In the described case, HPV type 18 was detected in pancreatic and cervical cancer specimens, which favored metastasis from cervical cancer rather than primary pancreatic cancer.

We report a rare case of pancreatic metastasis from cervical adenocarcinoma. Metastatic pancreatic tumors should be considered in patients presenting with a pancreatic mass, particularly those with a history of malignancy.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Abdominal computed tomography image showing a heterogeneously enhanced mass in the pancreatic body (white arrow).

Fig. 2

Magnetic resonance T2-weighted image showing a 3.5 cm mass in the pancreatic body (white dashed arrow).

Fig. 3

FDG PET/CT revealed abnormal FDG uptake in the pancreatic body (SUV max 5.9). FDG PET/CT, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography; SUV, standardized uptake value.

Fig. 4

Endoscopic ultrasound showed a hypoechoic mass in the pancreatic body; fine needle aspiration bioppsy was performed.

References

1. Kuwatani M, Kawakami H, Asaka M, Marukawa K, Matsuno Y, Hosaka M. Pancreatic metastasis from small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix demonstrated by endoscopic ultrasonographyguided fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008; 36:840–842.

2. Mackay B, Osborne BM, Wharton JT. Small cell tumor of cervix with neuroepithelial features: ultrastructural observations in two cases. Cancer. 1979; 43:1138–1145.

3. Ogawa H, Tsujie M, Miyamoto A, et al. Isolated pancreatic metastasis from uterine cervical cancer: a case report. Pancreas. 2011; 40:797–798.

4. Nishimura C, Naoe H, Hashigo S, et al. Pancreatic metastasis from mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2013; 6:256–262.

5. Wastell C. A solitary secondary deposit in the pancreas from a carcinoma of the cervix. Postgrad Med J. 1966; 42:59–61.

6. Ballarin R, Spaggiari M, Cautero N, et al. Pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: the state of the art. World J Gastroenterol. 2011; 17:4747–4756.

7. Takeuchi S. Biology and treatment of cervical adenocarcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016; 28:254–262.

8. Mahajan S, Pandit-Taskar N. Uncommon metastasis to the pancreas from adenocarcinoma of the cervix detected on surveillance 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 2017; 42:e511–e512.

9. Choi TW, Kim SH, Shin CI, Han JK, Choi BI. MDCT findings of pancreatic metastases according to primary tumors. Abdom Imaging. 2015; 40:1595–1607.

10. Chu PG, Schwarz RE, Lau SK, Yen Y, Weiss LM. Immunohistochemical staining in the diagnosis of pancreatobiliary and ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma: application of CDX2, CK17, MUC1, and MUC2. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:359–367.

11. McCluggage WG, Shah R, Connolly LE, McBride HA. Intestinaltype cervical adenocarcinoma in situ and adenocarcinoma exhibit a partial enteric immunophenotype with consistent expression of CDX2. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008; 27:92–100.

12. Ohtsubo K, Watanabe H, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Abnormalities of tumor suppressor gene p16 in pancreatic carcinoma: immunohistochemical and genetic findings compared with clinicopathological parameters. J Gastroenterol. 2003; 38:663–671.

13. Doxtader EE, Katzenstein AL. The relationship between p16 expression and high-risk human papillomavirus infection in squamous cell carcinomas from sites other than uterine cervix: a study of 137 cases. Hum Pathol. 2012; 43:327–332.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download