Abstract

Background/Aims

Colorectal cancer (CRC) with microsatellite instability (MSI) has a better prognosis than CRC with microsatellite stable (MSS). Recent studies have reported biological differences according to tumor location in CRC. In this study, we investigated the clinical significance of MSI in patients with right-sided CRC.

Methods

The medical records of 1,009 CRC patients diagnosed at our institute between October 2004 and December 2016 with MSI test results were retrospectively reviewed. The long-term outcomes of CRC patients with MSI were assessed with respect to tumor location using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression models.

Results

The median follow-up duration for all 1,009 study subjects was 25 months (interquartile range, 15–38). One hundred twenty-four of the study subjects had MSI (12.3%) and 250 had right-sided CRC (24.8%). The patients with MSI and right-sided CRC had better disease-free survival (DFS) than those with MSS as determined by the log-rank test (p=0.013), and this result was significant in females (p=0.035) but not in males with right-sided CRC. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed MSS significantly predicted poor DFS in patients with right-sided CRC (hazard ratio 3.97, 95% CI 1.30–12.15, p=0.016) and in female patients (hazard ratio 4.69, 95% CI 1.03–21.36, p=0.045).

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common tumor in men and the second most common tumor in women worldwide.1 According to World Health Organization data, the incidence of CRC in Korea is the highest in the world with an age-standardized death rate of 45 per 100,000.2 Although the 5-year survival rate of CRC has increased over the past few years, this disease is still the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.3 CRC is a heterogeneous complex of diseases that results from accumulations of distinct genetic and epigenetic alterations.4

Microsatellites are tandem repeats of short DNA sequences, and microsatellite instability (MSI) is a hypermutation phenotype caused by germ-line or somatic mutation of a mismatch repair gene or by hypermethylation of mismatch repair promotor gene.5 MSI is found in 15% of sporadic CRC cases and has also been reported in tumors of the stomach, ovaries, urinary tract, kidneys, and liver.6 According to a systemic review of MSI in CRC, MSI is a good prognostic marker for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with a locally advanced colorectal tumor.7 CRC patients with MSI are known to predominantly develop right-sided colon cancer with a mucinous and poorly differentiated histology and to have a better prognosis than those with microsatellite stable (MSS).8 Furthermore, recent studies suggest MSI may be a predictable marker for immunotherapy and have shown CRC patients with MSI-high (MSI-H) have better responses to immune checkpoint blockade therapy.910

Commonly, CRC is classified by tumor location as right-sided or left-sided carcinoma, and interestingly, recent biological and clinical evidence indicates that the carciogenesis of proximal and distal CRCs follow different molecular pathways.4 Right-sided carcinomas are more prevalent in females and have a lower incidence and more frequent BRAF mutations than left-sided carcinomas and have a mucinous histology.11 In the CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial, metastatic CRCs arising in the right colon were found to be clinically different from those arising in the left, and tumor location was found to have prognostic and predictive value.12 Also, in the RAS wide type population of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 trials, patients with left-sided tumors had markedly better prognosis than those with right-sided tumors.13 In this study, we hypothesized that primary tumor location would influence the prognosis of CRC patients with MSI, and investigated the clinical significance of MSI in patients with right-sided CRC.

The medical records of patients diagnosed with CRC at Kosin University Gospel Hospital (Busan, Korea) between January 2004 and December 2016 were retrospectively reviewed, and 1,009 patients that underwent MSI testing were included in the analysis. We assessed the long-term outcomes of patients according to CRC location. Right-sided CRC was defined as CRC originating proximal to the splenic flexure, and left-sided CRC as CRC arising distal to this site. Detailed clinical data including patient ages, genders, tumor locations, histopathologies, tumor stages, and receipt of chemotherapy were collated. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kosin University Gospel Hospital (KUGH 2018-02-016).

MSI testing was conducted in accord with the Bethesda guidelines using a panel of five microsatellite loci, which was composed of three dinucleotide repeat markers (D2S123, D5S346, D17S250) and two mononucleotide repeat markers (BAT25 and BAT26). MSI-H was defined as instability in ≥2 or the 5 markers, and MSI-low (MSI-L) was defined as instability in one marker. MSS was defined as the absence of instability in any of the 5 markers.

Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined at time from date of CRC diagnosis to recurrence or final follow-up. Continuous and categorical variables were analyzed using the student's t-test or the chi-square test, as appropriate. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to differentiate the ability of MSI to predict long-term outcomes. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to construct survival curves based on cumulative incidences and survivals were compared using the log rank test. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess factors affecting DFS. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant, and the analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

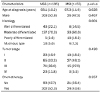

Between January 2004 and December 2016, 1,009 patients diagnosed with CRC underwent MSI testing; 250 patients had right-sided CRC and 759 patients had left-sided CRC. Patient baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Tumor locations (right- or left-sided) were not significantly related to age, histology, or tumor stage, but differed significantly by gender. The median follow-up duration was 25 months (interquartile range, 15–38).

One hundred twenty-four (12.3%) of the 1,009 study subjects had MSI; 55 patients had right-sided CRC and 69 had left-sided CRC, which was a significant difference (22.0% vs. 9.1%, p<0.001) (Table 1). In the 75 patients with MSI-H, 44 had right-sided CRC (17.6%) and 31 had left-sided CRC (4.1%), which was also significant. However, in the 49 patients with MSI-L, 11 had right-sided CRC (4.4%) and 38 had left-sided CRC (5.0%), and this difference was not significant.

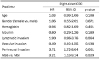

For right-sided CRC, patients with MSI (MSI-L or MSI-H) had a significantly higher mean DFS than patients with MSS (p=0.013), but this was not observed in left-sided CRC (p=0.846) (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of patients with right-sided CRC according to MSI status are summarized in Table 2. No significant differences were observed between patients with MSI or MSS with respect to age, sex, or tumor stage, but histologies differed significantly. Furthermore, female patients with MSI and right-sided CRC had a significantly higher mean DFS than those with MSS (p=0.035), but this was not observed for female patients with left-sided CRC (p=0.319) (Fig. 2). However, no significant difference was observed between the mean DFSs of male patients with right-or left-sided CRC and MSI or MSS (Fig. 3). Furthermore, no significant association was observed between tumor stage and microsatellite status or CRC sidedness (Fig. 4).

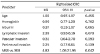

Cox regression analysis was used to identify clinicopathologic factors that affected the DFS of patients with right-sided CRC. Multivariate analysis showed perineural invasion and MSI were significant prognostic factors in patients with right-sided CRC. More specifically, right-sided CRC patients with perineural invasion had poorer DFS than those without (hazard ratio [HR] 3.71, 95% CI 1.72-8.04, p=0.001), and patients with MSS had poorer DFS than those with MSI (HR 3.21, 95% CI 1.13-9.14, p=0.029) (Table 3). No such relations were not found for left-sided CRC.

Multivariate analysis of male and female patients with right-sided CRC showed MSS significantly affected DFS (MSS vs. MSI, HR 4.83, 95% CI 1.06-21.95, p=0.042) but not peri-neural invasion in right-sided CRC (Table 4). No such relations were observed for male patients with right-sided CRC.

This study shows, especially for women, right-sided CRC patients with MSI have a better prognosis than right-sided patients with MSS and that MSI is a useful prognostic factor of long-term outcome in right-sided CRC. Although MSI is found in only ~15% of sporadic CRC patients, it is considered a good prognostic marker in CRC and a predictable marker for immunotherapy.791415 According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, stage II CRC patients with MSI-H may have a good prognosis and do not benefit from 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy.16 Conversely, it is recommended adjuvant chemotherapy be considered for stage II CRC patients with MSI-L or MSS.16 In the present study, subanalysis was performed on patients with MSI-H or MSI-L and right- or left-sided CRC. The analysis showed for right-sided CRC, patients with MSI (MSI-L or MSI-H) had a lower mean recurrence rate than patients with MSS. Pawlik et al.17 found MSI-H tumors usually arise from epigenetic silencing of the mismatch repair gene MLH1, and that MSI-L tumors, like MSS tumors, appear to arise through the chromosomal instability carcinogenesis pathway. Nazemalhosseini et al.18 reported that CRC patients with MSI-L had a poorer survival rate than patients with MSI-H or MSS tumors. Additional studies are required to clarify the role played by MSI-L in CRC. In the present study, only 49 of the study subjects had MSI-L, and of these only 11 patients had MSI-L and right-sided CRC. Notably, no recurrence occurred in patients with right-sided CRC and MSI-L, but 4 (9.1%) of the 44 right-sided CRC patients with MSI-H, and 41 (21.0%) of the 195 right-sided CRC patients with MSS experienced recurrence (data not shown).

Some studies have reported left-sided CRC has a better prognosis than right-sided CRC, because left-sided CRC can be diagnosed at an early stage by sigmoidoscopy or by apparent symptoms, such as rectal bleeding.192021 Patients with right-sided CRC are more likely to be older, female, be diagnosed with more advanced disease, and to have poorly differentiated tumors.21 A systemic review and meta-analysis showed patients with right-sided CRC had a significantly poorer prognosis than left-sided CRC, and it was suggested right-sided CRC patients should be treated differently from left-sided CRC patients.22 In the present study, we investigated prognostic factors in patients with right-sided CRC, and interestingly, we noticed the proportion of poorly differentiated or mucinous tumors in MSI was significantly greater than in MSS (Table 2), and that the long-term outcomes of patients with MSI were better than those of patients with MSS. Furthermore, we found MSI usefully predicted long-term outcomes in patients with right-sided CRC.

Recently, gender-associated differences in CRC have attracted considerable interest. Some have reported epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in liver differs between female and male mice, and suggested this difference may influence the prognosis of CRC patients with liver metastasis.2324 In a retrospective cohort study of 39,325 CRC patients that underwent surgical resection, it was shown women presented more emergently and at an older age and had a longer adjusted survival than men.25 In addition, a recent meta-analysis concluded female CRC patients had significantly better overall survival and cancer-specific survival rates than male CRC patients.26 In the present study, female right-sided CRC patients with MSI had a significantly better prognosis than those with MSS. Although further studies are needed, these results suggest that gender significantly affects the long-term outcomes of CRC patients.

This study had some limitations that warrant mention. First, it is limited by its retrospective, single center design, which means selection bias could not be avoided, though we did try to minimize bias by repeatedly reviewing medical records. Second, the male to female ratios of patients with right-sided and left-sided CRC were significantly different. To address this shortcoming, we performed sub-group analysis by gender in patients with right-sided and left-sided CRC.

In conclusion, the present study shows MSI usefully predicts DFS in patients with right-sided CRC, especially in female patients. Based on the results of this study, we suggest MSI, tumor location, and gender are important considerations during initial assessments in terms of the prediction of long-term outcomes.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Kaplan-Meier curves showing disease free survivals of colorectal cancer patients according to MSI status and tumor location. CRC, colorectal cancer; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable. |

| Fig. 2Kaplan-Meier curves showing disease free survivals of female colorectal cancer patients according to MSI status and tumor location. CRC, colorectal cancer; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable. |

| Fig. 3Kaplan-Meier curves showing disease free survivals of male colorectal cancer patients according to MSI status and tumor location. CRC, colorectal cancer; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable. |

| Fig. 4Kaplan-Meier curves showing disease free survivals of colorectal cancer patients according to MSI status and tumor stage. CRC, colorectal cancer; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable. |

References

1. Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010; 116:544–573.

Cancer Today: data visualization tools for exploring the global cancer burden in 2018. [Internet]. Lyon: International Association of Cancer Registries;c2018. cited 2018 Dec 20. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home.

4. Loupakis F, Yang D, Yau L, et al. Primary tumor location as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015; 107:dju427.

5. Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2073–2087.e3.

6. Cortes-Ciriano I, Lee S, Park WY, Kim TM, Park PJ. A molecular portrait of microsatellite instability across multiple cancers. Nat Commun. 2017; 8:15180.

7. Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:609–618.

8. Aaltonen LA, Salovaara R, Kristo P, et al. Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338:1481–1487.

9. Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017; 357:409–413.

10. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2509–2520.

11. Benedix F, Schmidt U, Mroczkowski P, et al. Colon carcinoma--classification into right and left sided cancer or according to colonic subsite?--analysis of 29,568 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011; 37:134–139.

12. Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti F, et al. Impact of primary (1°) tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34:15 Suppl. 3504.

13. Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, et al. Prognostic and predictive relevance of primary tumor location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: retrospective analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017; 3:194–201.

14. Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Thibodeau SN, et al. DNA mismatch repair status and colon cancer recurrence and survival in clinical trials of 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011; 103:863–875.

15. Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:3219–3226.

16. NCCN guidelines® & clinical resources. [Internet]. Plymouth Meeting (PA): National Comprehensive Cancer Network;c2018. updated 2018 Oct 19. cited 2018 Dec 20. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#colon.

17. Pawlik TM, Raut CP, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. Colorectal carcinogenesis: MSI-H versus MSI-L. Dis Markers. 2004; 20:199–206.

18. Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Kashfi SM, Mirtalebi H, et al. Low level of microsatellite instability correlates with poor clinical prognosis in stage II colorectal cancer patients. J Oncol. 2016; 2016:2196703.

19. Nawa T, Kato J, Kawamoto H, et al. Differences between right- and left-sided colon cancer in patient characteristics, cancer morphology and histology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008; 23:418–423.

20. Roncucci L, Fante R, Losi L, et al. Survival for colon and rectal cancer in a population-based cancer registry. Eur J Cancer. 1996; 32A:295–302.

21. Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O'Connor ES, et al. Mortality by stage for rightversus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results--medicare data. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:4401–4409.

22. Yahagi M, Okabayashi K, Hasegawa H, Tsuruta M, Kitagawa Y. The worse prognosis of right-sided compared with left-sided colon cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016; 20:648–655.

23. Liu F, Jiao Y, Jiao Y, Garcia-Godoy F, Gu W, Liu Q. Sex difference in EGFR pathways in mouse kidney-potential impact on the immune system. BMC Genet. 2016; 17:146.

24. Wang L, Xiao J, Gu W, Chen H. Sex difference of egfr expression and molecular pathway in the liver: impact on drug design and cancer treatments. J Cancer. 2016; 7:671–680.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download