1. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 175:367–416. PMID:

17277290.

2. Haworth CS, Banks J, Capstick T, Fisher AJ, Gorsuch T, Laurenson IF, et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD). Thorax. 2017; 72(Suppl 2):ii1–ii64.

3. Runyon EH. Anonymous mycobacteria in pulmonary disease. Med Clin North Am. 1959; 43:273–290. PMID:

13612432.

4. Griffith DE, Aksamit TR. Understanding nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease: it's been a long time coming. F1000Res. 2016; 5:2797. PMID:

27990278.

6. Ryu YJ, Koh WJ, Daley CL. Diagnosis and treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease: clinicians' perspectives. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2016; 79:74–84.

7. Stout JE, Koh WJ, Yew WW. Update on pulmonary disease due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Int J Infect Dis. 2016; 45:123–134. PMID:

26976549.

8. Wallace RJ Jr, Zhang Y, Brown-Elliott BA, Yakrus MA, Wilson RW, Mann L, et al. Repeat positive cultures in

Mycobacterium intracellulare lung disease after macrolide therapy represent new infections in patients with nodular bronchiectasis. J Infect Dis. 2002; 186:266–273. PMID:

12134265.

9. Wallace RJ Jr, Brown-Elliott BA, McNulty S, Philley JV, Killingley J, Wilson RW, et al. Macrolide/Azalide therapy for nodular/bronchiectatic mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Chest. 2014; 146:276–282. PMID:

24457542.

10. Koh WJ, Moon SM, Kim SY, Woo MA, Kim S, Jhun BW, et al. Outcomes of

Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease based on clinical phenotype. Eur Respir J. 2017; 50:1602503. PMID:

28954780.

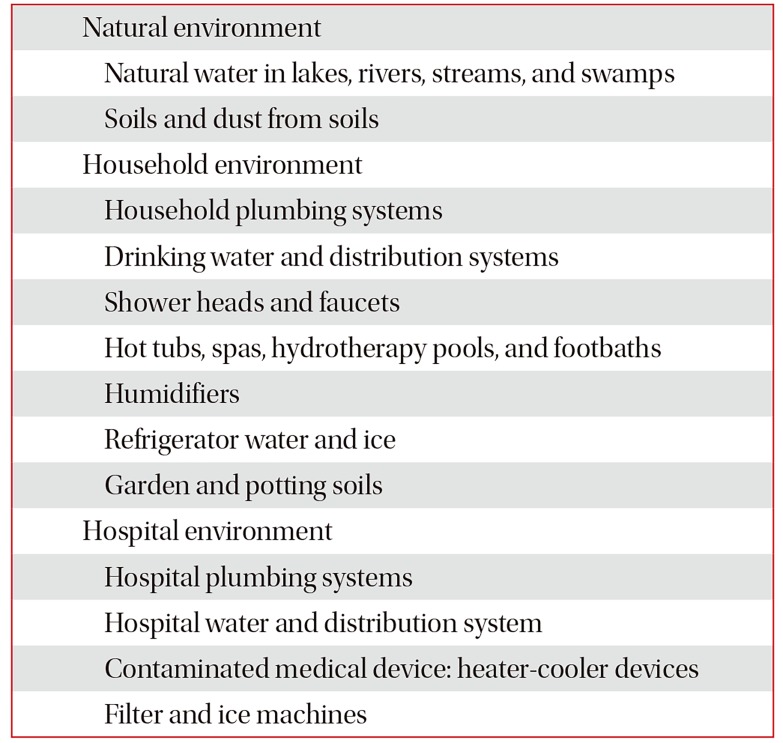

11. Falkinham JO 3rd. Surrounded by mycobacteria: nontuberculous mycobacteria in the human environment. J Appl Microbiol. 2009; 107:356–367. PMID:

19228258.

12. Falkinham JO 3rd. Environmental sources of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Chest Med. 2015; 36:35–41. PMID:

25676517.

13. Brennan PJ, Nikaido H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995; 64:29–63. PMID:

7574484.

14. Bodmer T, Miltner E, Bermudez LE. Mycobacterium avium resists exposure to the acidic conditions of the stomach. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000; 182:45–49. PMID:

10612729.

15. Rastogi N, Frehel C, Ryter A, Ohayon H, Lesourd M, David HL. Multiple drug resistance in Mycobacterium avium: is the wall architecture responsible for exclusion of antimicrobial agents? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981; 20:666–677. PMID:

6798925.

16. Taylor RH, Falkinham JO 3rd, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW. Chlorine, chloramine, chlorine dioxide, and ozone susceptibility of

Mycobacterium avium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000; 66:1702–1705. PMID:

10742264.

17. Schulze-Robbecke R, Buchholtz K. Heat susceptibility of aquatic mycobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992; 58:1869–1873. PMID:

1622262.

18. Cirillo JD, Falkow S, Tompkins LS, Bermudez LE. Interaction of

Mycobacterium avium with environmental amoebae enhances virulence. Infect Immun. 1997; 65:3759–3767. PMID:

9284149.

19. Faria S, Joao I, Jordao L. General overview on nontuberculous mycobacteria, biofilms, and human infection. J Pathog. 2015; 2015:809014. PMID:

26618006.

20. Parker BC, Ford MA, Gruft H, Falkinham JO 3rd. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. IV. Preferential aerosolization of

Mycobacterium intracellulare from natural waters. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983; 128:652–656. PMID:

6354024.

21. Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Falkinham JO 3rd, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Spatial clusters of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012; 186:553–558. PMID:

22773732.

22. Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR. Nontuberculous mycobacteria among patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States: screening practices and environmental risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014; 190:581–586. PMID:

25068291.

23. Nishiuchi Y, Iwamoto T, Maruyama F. Infection sources of a common non-tuberculous mycobacterial pathogen,

Mycobacterium avium complex. Front Med (Lausanne). 2017; 4:27. PMID:

28326308.

24. Thomson R, Tolson C, Sidjabat H, Huygens F, Hargreaves M.

Mycobacterium abscessus isolated from municipal water: a potential source of human infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013; 13:241. PMID:

23705674.

25. Torvinen E, Suomalainen S, Lehtola MJ, Miettinen IT, Zacheus O, Paulin L, et al. Mycobacteria in water and loose deposits of drinking water distribution systems in Finland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004; 70:1973–1981. PMID:

15066787.

26. Tuffley RE, Holbeche JD. Isolation of the

Mycobacterium avium-

M. intracellulare-

M. scrofulaceum complex from tank water in Queensland, Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980; 39:48–53. PMID:

7356321.

27. Falkinham JO 3rd, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW. Factors influencing numbers of

Mycobacterium avium,

Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001; 67:1225–1231. PMID:

11229914.

28. Falkinham JO 3rd. Nontuberculous mycobacteria from household plumbing of patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011; 17:419–424. PMID:

21392432.

29. Thomson R, Tolson C, Carter R, Coulter C, Huygens F, Hargreaves M. Isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from household water and shower aerosols in patients with pulmonary disease caused by NTM. J Clin Microbiol. 2013; 51:3006–3011. PMID:

23843489.

30. Falkinham JO 3rd, Iseman MD, de Haas P, van Soolingen D.

Mycobacterium avium in a shower linked to pulmonary disease. J Water Health. 2008; 6:209–213. PMID:

18209283.

31. Feazel LM, Baumgartner LK, Peterson KL, Frank DN, Harris JK, Pace NR. Opportunistic pathogens enriched in showerhead biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106:16393–16399. PMID:

19805310.

32. von Reyn CF, Maslow JN, Barber TW, Falkinham JO 3rd, Arbeit RD. Persistent colonisation of potable water as a source of

Mycobacterium avium infection in AIDS. Lancet. 1994; 343:1137–1141. PMID:

7910236.

33. Reznikov M, Dawson DJ. Serological investigation of strains of

Mycobacterium intracellulare (“battey” bacillus) isolated from house-dusts. Med J Aust. 1971; 1:682–683. PMID:

5553815.

34. De Groote MA, Pace NR, Fulton K, Falkinham JO 3rd. Relationships between Mycobacterium isolates from patients with pulmonary mycobacterial infection and potting soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006; 72:7602–7606. PMID:

17056679.

35. Sood G, Parrish N. Outbreaks of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017; 30:404–409. PMID:

28548990.

36. Allen KB, Yuh DD, Schwartz SB, Lange RA, Hopkins R, Bauer K, et al. Nontuberculous

Mycobacterium infections associated with heater-cooler devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017; 104:1237–1242. PMID:

28821331.

37. Williamson D, Howden B, Stinear T.

Mycobacterium chimaera spread from heating and cooling units in heart surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:600–602. PMID:

28177865.

38. Prevots DR, Adjemian J, Fernandez AG, Knowles MR, Olivier KN. Environmental risks for nontuberculous mycobacteria: individual exposures and climatic factors in the cystic fibrosis population. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014; 11:1032–1038. PMID:

25068620.

39. Halstrom S, Price P, Thomson R. Review: environmental mycobacteria as a cause of human infection. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2015; 4:81–91. PMID:

26972876.

40. O'Brien DP, Currie BJ, Krause VL. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in northern Australia: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000; 31:958–967. PMID:

11049777.

41. Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Greaves D, Foweraker J, Roddick I, Inns T, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of

Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2013; 381:1551–1560. PMID:

23541540.

42. Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Rodriguez-Rincon D, Everall I, Brown KP, Moreno P, et al. Emergence and spread of a human-transmissible multidrug-resistant nontuberculous mycobacterium. Science. 2016; 354:751–757. PMID:

27846606.

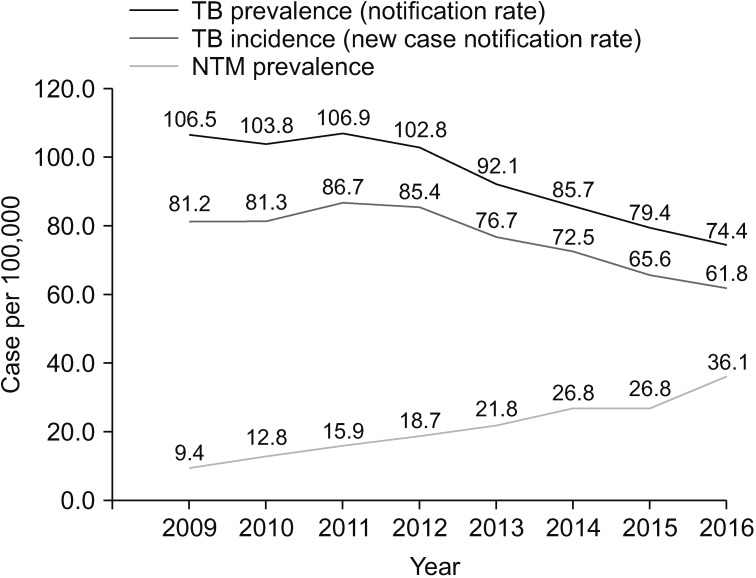

43. Prevots DR, Loddenkemper R, Sotgiu G, Migliori GB. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an increasing burden with substantial costs. Eur Respir J. 2017; 49:1700374. PMID:

28446563.

44. Prevots DR, Marras TK. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a review. Clin Chest Med. 2015; 36:13–34. PMID:

25676516.

45. Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012; 185:881–886. PMID:

22312016.

46. Marras TK, Mendelson D, Marchand-Austin A, May K, Jamieson FB. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease, Ontario, Canada, 1998–2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013; 19:1889–1891. PMID:

24210012.

47. Moore JE, Kruijshaar ME, Ormerod LP, Drobniewski F, Abubakar I. Increasing reports of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1995-2006. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10:612. PMID:

20950421.

48. Thomson RM. NTM working group at Queensland TB Control Centre and Queensland Mycobacterial Reference Laboratory. Changing epidemiology of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:1576–1583. PMID:

20875283.

49. Ide S, Nakamura S, Yamamoto Y, Kohno Y, Fukuda Y, Ikeda H, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteriosis in Nagasaki, Japan. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0128304. PMID:

26020948.

50. Lai CC, Tan CK, Chou CH, Hsu HL, Liao CH, Huang YT, et al. Increasing incidence of nontuberculous mycobacteria, Taiwan, 2000–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:294–296. PMID:

20113563.

51. Kwon YS, Koh WJ. Diagnosis and treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31:649–659. PMID:

27134484.

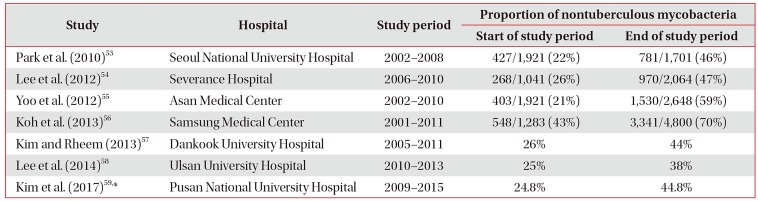

52. Ko RE, Moon SM, Ahn S, Jhun BW, Jeon K, Kwon OJ, et al. Changing epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung diseases in a tertiary referral hospital in Korea between 2001 and 2015. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33:e65. PMID:

29441757.

53. Park YS, Lee CH, Lee SM, Yang SC, Yoo CG, Kim YW, et al. Rapid increase of non-tuberculous mycobacterial lung diseases at a tertiary referral hospital in South Korea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010; 14:1069–1071. PMID:

20626955.

54. Lee SK, Lee EJ, Kim SK, Chang J, Jeong SH, Kang YA. Changing epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in South Korea. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012; 44:733–738. PMID:

22720876.

55. Yoo JW, Jo KW, Kim MN, Lee SD, Kim WS, Kim DS, et al. Increasing trend of isolation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in a tertiary university hospital in South Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2012; 72:409–415.

56. Koh WJ, Chang B, Jeong BH, Jeon K, Kim SY, Lee NY, et al. Increasing recovery of nontuberculous mycobacteria from respiratory specimens over a 10-year period in a tertiary referral hospital in South Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2013; 75:199–204.

57. Kim JK, Rheem I. Identification and distribution of nontuberculous mycobacteria from 2005 to 2011 in Cheonan, Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2013; 74:215–221.

58. Lee MY, Lee T, Kim MH, Byun SS, Ko MK, Hong JM, et al. Regional differences of nontuberculous mycobacteria species in Ulsan, Korea. J Thorac Dis. 2014; 6:965–970. PMID:

25093094.

59. Kim N, Yi J, Chang CL. Recovery rates of non-tuberculous mycobacteria from clinical specimens are increasing in Korean tertiary-care hospitals. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32:1263–1267. PMID:

28665061.

60. Yoon HJ, Choi HY, Ki M. Nontuberculosis mycobacterial infections at a specialized tuberculosis treatment centre in the Republic of Korea. BMC Infect Dis. 2017; 17:432. PMID:

28619015.

61. Brode SK, Daley CL, Marras TK. The epidemiologic relationship between tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014; 18:1370–1377. PMID:

25299873.

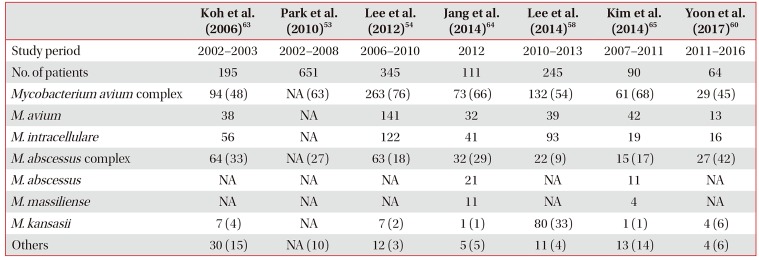

62. Hoefsloot W, van Ingen J, Andrejak C, Angeby K, Bauriaud R, Bemer P, et al. The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. Eur Respir J. 2013; 42:1604–1613. PMID:

23598956.

63. Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Jeon K, Kim TS, Lee KS, Park YK, et al. Clinical significance of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from respiratory specimens in Korea. Chest. 2006; 129:341–348. PMID:

16478850.

64. Jang MA, Koh WJ, Huh HJ, Kim SY, Jeon K, Ki CS, et al. Distribution of nontuberculous mycobacteria by multigene sequence-based typing and clinical significance of isolated strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2014; 52:1207–1212. PMID:

24501029.

65. Kim HS, Lee Y, Lee S, Kim YA, Sun YK. Recent trends in clinically significant nontuberculous mycobacteria isolates at a Korean general hospital. Ann Lab Med. 2014; 34:56–59. PMID:

24422197.

66. Honda JR, Knight V, Chan ED. Pathogenesis and risk factors for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 2015; 36:1–11. PMID:

25676515.

67. Kartalija M, Ovrutsky AR, Bryan CL, Pott GB, Fantuzzi G, Thomas J, et al. Patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease exhibit unique body and immune phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013; 187:197–205. PMID:

23144328.

68. Kim RD, Greenberg DE, Ehrmantraut ME, Guide SV, Ding L, Shea Y, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease: prospective study of a distinct preexisting syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008; 178:1066–1074. PMID:

18703788.

69. Szymanski EP, Leung JM, Fowler CJ, Haney C, Hsu AP, Chen F, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a multisystem, multigenic disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 192:618–628. PMID:

26038974.

70. Yeung MW, Khoo E, Brode SK, Jamieson FB, Kamiya H, Kwong JC, et al. Health-related quality of life, comorbidities and mortality in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: a systematic review. Respirology. 2016; 21:1015–1025. PMID:

27009804.

71. Novosad SA, Henkle E, Schafer S, Hedberg K, Ku J, Siegel SA, et al. Mortality after respiratory isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria: a comparison of patients who did and did not meet disease criteria. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017; 14:1112–1119. PMID:

28387532.

72. Huang CT, Tsai YJ, Wu HD, Wang JY, Yu CJ, Lee LN, et al. Impact of non-tuberculous mycobacteria on pulmonary function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012; 16:539–545. PMID:

22325332.

73. Park HY, Jeong BH, Chon HR, Jeon K, Daley CL, Koh WJ. Lung function decline according to clinical course in nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Chest. 2016; 150:1222–1232. PMID:

27298072.

74. Diel R, Jacob J, Lampenius N, Loebinger M, Nienhaus A, Rabe KF, et al. Burden of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in Germany. Eur Respir J. 2017; 49:1602109. PMID:

28446559.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download