|

1 |

Tuberculosis |

0.519 |

0.462 |

0.575 |

|

2 |

HIV disease resulting in mycobacterial infection |

0.746 |

0.694 |

0.792 |

|

3 |

HIV disease resulting in other specified or unspecified diseases |

0.787 |

0.740 |

0.828 |

|

4 |

Cholera |

0.355 |

0.298 |

0.415 |

|

5 |

Other salmonella infections |

0.279 |

0.229 |

0.334 |

|

6 |

Shigellosis |

0.248 |

0.198 |

0.303 |

|

7 |

Enteropathogenic E. coli infection |

0.290 |

0.236 |

0.347 |

|

8 |

Enterotoxigenic E. coli infection |

0.267 |

0.216 |

0.323 |

|

9 |

Campylobacter enteritis |

0.268 |

0.218 |

0.324 |

|

10 |

Amoebiasis |

0.380 |

0.321 |

0.440 |

|

11 |

Cryptosporidiosis |

0.518 |

0.459 |

0.577 |

|

12 |

Rotaviral enteritis |

0.188 |

0.146 |

0.236 |

|

13 |

Intestinal infection |

0.270 |

0.217 |

0.327 |

|

14 |

Typhoid and paratyphoid fevers |

0.382 |

0.322 |

0.445 |

|

15 |

Influenza |

0.149 |

0.112 |

0.194 |

|

16 |

Pneumococcal pneumonia |

0.427 |

0.369 |

0.486 |

|

17 |

H. influenzae type B pneumonia |

0.407 |

0.348 |

0.468 |

|

18 |

Respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia |

0.367 |

0.309 |

0.428 |

|

19 |

Upper respiratory infections |

0.131 |

0.096 |

0.173 |

|

20 |

Otitis media |

0.176 |

0.134 |

0.224 |

|

21 |

Pneumococcal meningitis |

0.590 |

0.532 |

0.645 |

|

22 |

H. influenzae type B meningitis |

0.557 |

0.498 |

0.614 |

|

23 |

Meningococcal infection |

0.530 |

0.470 |

0.588 |

|

24 |

Encephalitis |

0.687 |

0.632 |

0.737 |

|

25 |

Diphtheria |

0.340 |

0.284 |

0.398 |

|

26 |

Whooping cough |

0.253 |

0.203 |

0.307 |

|

27 |

Tetanus |

0.525 |

0.466 |

0.583 |

|

28 |

Measles |

0.254 |

0.203 |

0.312 |

|

29 |

Varicella |

0.241 |

0.193 |

0.293 |

|

30 |

Malaria |

0.438 |

0.381 |

0.497 |

|

31 |

Chagas disease |

0.547 |

0.489 |

0.604 |

|

32 |

Leishmaniasis |

0.408 |

0.350 |

0.467 |

|

33 |

African trypanosomiasis |

0.432 |

0.376 |

0.490 |

|

34 |

Schistosomiasis |

0.381 |

0.323 |

0.442 |

|

35 |

Cysticercosis |

0.372 |

0.316 |

0.431 |

|

36 |

Echinococcosis |

0.412 |

0.354 |

0.471 |

|

37 |

Lymphatic filariasis |

0.418 |

0.359 |

0.479 |

|

38 |

Onchocerciasis |

0.319 |

0.264 |

0.378 |

|

39 |

Trachoma |

0.437 |

0.376 |

0.498 |

|

40 |

Dengue |

0.395 |

0.337 |

0.455 |

|

41 |

Yellow fever |

0.504 |

0.444 |

0.563 |

|

42 |

Rabies |

0.655 |

0.598 |

0.709 |

|

43 |

Ascariasis |

0.231 |

0.183 |

0.284 |

|

44 |

Trichuriasis |

0.253 |

0.202 |

0.309 |

|

45 |

Hookworm disease |

0.241 |

0.193 |

0.295 |

|

46 |

Food-borne trematodiases |

0.275 |

0.224 |

0.330 |

|

47 |

Tsutsugamushi fever |

0.386 |

0.329 |

0.445 |

|

48 |

Typhus fever |

0.390 |

0.332 |

0.449 |

|

49 |

Hantaan virus disease |

0.472 |

0.411 |

0.532 |

|

50 |

Intestinal helminth |

0.267 |

0.217 |

0.321 |

|

51 |

Maternal hemorrhage |

0.514 |

0.453 |

0.575 |

|

52 |

Maternal sepsis |

0.749 |

0.699 |

0.795 |

|

53 |

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy |

0.455 |

0.395 |

0.516 |

|

54 |

Obstructed labor |

0.462 |

0.404 |

0.521 |

|

55 |

Abortion |

0.300 |

0.245 |

0.359 |

|

56 |

Preterm birth complications |

0.517 |

0.456 |

0.576 |

|

57 |

Neonatal encephalopathy (birth asphyxia and birth trauma) |

0.858 |

0.815 |

0.893 |

|

58 |

Sepsis and other infectious disorders of the newborn baby |

0.711 |

0.658 |

0.759 |

|

59 |

Protein-energy malnutrition |

0.414 |

0.356 |

0.474 |

|

60 |

Iodine deficiency |

0.200 |

0.155 |

0.250 |

|

61 |

Vitamin A deficiency |

0.153 |

0.115 |

0.197 |

|

62 |

Iron-deficiency anemia |

0.170 |

0.131 |

0.216 |

|

63 |

Syphilis |

0.452 |

0.393 |

0.511 |

|

64 |

Sexually transmitted chlamydial diseases |

0.253 |

0.205 |

0.307 |

|

65 |

Gonococcal infection |

0.307 |

0.255 |

0.364 |

|

66 |

Trichomoniasis |

0.316 |

0.259 |

0.377 |

|

67 |

Herpes genitalia |

0.286 |

0.231 |

0.345 |

|

68 |

Acute hepatitis A |

0.364 |

0.307 |

0.424 |

|

69 |

Acute hepatitis B |

0.431 |

0.372 |

0.491 |

|

70 |

Acute hepatitis C |

0.501 |

0.441 |

0.561 |

|

71 |

Acute hepatitis E |

0.467 |

0.407 |

0.526 |

|

72 |

Leprosy |

0.613 |

0.558 |

0.665 |

|

73 |

Legionnaires' disease |

0.345 |

0.288 |

0.405 |

|

74 |

Leptospirosis |

0.415 |

0.355 |

0.475 |

|

75 |

Rubella |

0.359 |

0.301 |

0.418 |

|

76 |

Mumps |

0.202 |

0.157 |

0.253 |

|

77 |

Esophageal cancer |

0.841 |

0.802 |

0.875 |

|

78 |

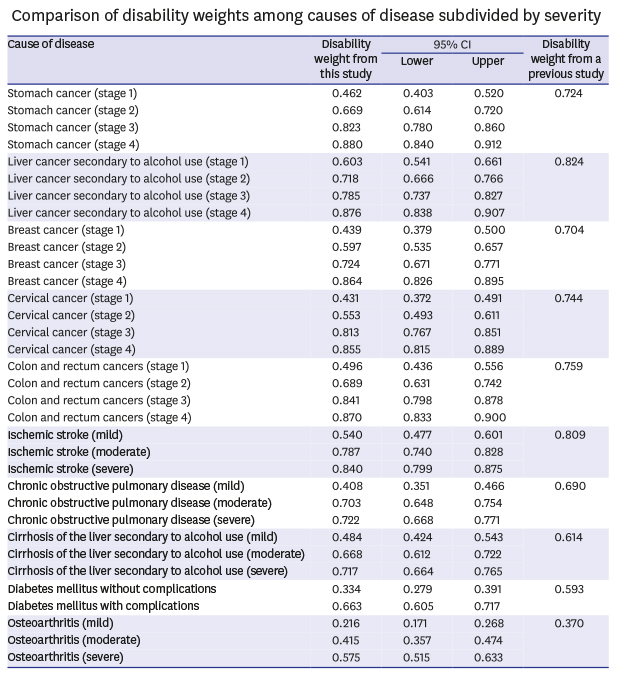

Stomach cancer (stage 1) |

0.462 |

0.403 |

0.520 |

|

79 |

Stomach cancer (stage 2) |

0.669 |

0.614 |

0.720 |

|

80 |

Stomach cancer (stage 3) |

0.823 |

0.780 |

0.860 |

|

81 |

Stomach cancer (stage 4) |

0.880 |

0.840 |

0.912 |

|

82 |

Liver cancer secondary to hepatitis B |

0.796 |

0.749 |

0.837 |

|

83 |

Liver cancer secondary to hepatitis C |

0.802 |

0.755 |

0.842 |

|

84 |

Liver cancer secondary to alcohol use (stage 1) |

0.603 |

0.541 |

0.661 |

|

85 |

Liver cancer secondary to alcohol use (stage 2) |

0.718 |

0.666 |

0.766 |

|

86 |

Liver cancer secondary to alcohol use (stage 3) |

0.785 |

0.737 |

0.827 |

|

87 |

Liver cancer secondary to alcohol use (stage 4) |

0.876 |

0.838 |

0.907 |

|

88 |

Larynx cancer |

0.824 |

0.784 |

0.859 |

|

89 |

Trachea, bronchus and lung cancers (stage 1) |

0.600 |

0.542 |

0.656 |

|

90 |

Trachea, bronchus and lung cancers (stage 2) |

0.738 |

0.686 |

0.785 |

|

91 |

Trachea, bronchus and lung cancers (stage 3) |

0.758 |

0.710 |

0.801 |

|

92 |

Trachea, bronchus and lung cancers (stage 4) |

0.906 |

0.873 |

0.932 |

|

93 |

Breast cancer (stage 1) |

0.439 |

0.379 |

0.500 |

|

94 |

Breast cancer (stage 2) |

0.597 |

0.535 |

0.657 |

|

95 |

Breast cancer (stage 3) |

0.724 |

0.671 |

0.771 |

|

96 |

Breast cancer (stage 4) |

0.864 |

0.826 |

0.895 |

|

97 |

Cervical cancer (stage 1) |

0.431 |

0.372 |

0.491 |

|

98 |

Cervical cancer (stage 2) |

0.553 |

0.493 |

0.611 |

|

99 |

Cervical cancer (stage 3) |

0.813 |

0.767 |

0.851 |

|

100 |

Cervical cancer (stage 4) |

0.855 |

0.815 |

0.889 |

|

101 |

Uterine cancer |

0.711 |

0.661 |

0.757 |

|

102 |

Prostate cancer (stage 1) |

0.458 |

0.399 |

0.518 |

|

103 |

Prostate cancer (stage 2) |

0.613 |

0.552 |

0.672 |

|

104 |

Prostate cancer (stage 3) |

0.742 |

0.692 |

0.787 |

|

105 |

Prostate cancer (stage 4) |

0.838 |

0.795 |

0.874 |

|

106 |

Colon and rectum cancers (stage 1) |

0.496 |

0.436 |

0.556 |

|

107 |

Colon and rectum cancers (stage 2) |

0.689 |

0.631 |

0.742 |

|

108 |

Colon and rectum cancers (stage 3) |

0.841 |

0.798 |

0.878 |

|

109 |

Colon and rectum cancers (stage 4) |

0.870 |

0.833 |

0.900 |

|

110 |

Mouth cancer |

0.870 |

0.828 |

0.905 |

|

111 |

Nasopharynx cancer |

0.766 |

0.716 |

0.811 |

|

112 |

Cancer of other part of pharynx and oropharynx |

0.811 |

0.764 |

0.851 |

|

113 |

Gallbladder and biliary tract cancer |

0.800 |

0.752 |

0.843 |

|

114 |

Pancreatic cancer |

0.879 |

0.843 |

0.909 |

|

115 |

Malignant melanoma of skin |

0.786 |

0.737 |

0.829 |

|

116 |

Non-melanoma skin cancer |

0.649 |

0.593 |

0.702 |

|

117 |

Ovarian cancer |

0.776 |

0.727 |

0.821 |

|

118 |

Testicular cancer |

0.692 |

0.637 |

0.744 |

|

119 |

Kidney cancer (stage 1) |

0.570 |

0.509 |

0.627 |

|

120 |

Kidney cancer (stage 2) |

0.731 |

0.678 |

0.778 |

|

121 |

Kidney cancer (stage 3) |

0.809 |

0.762 |

0.849 |

|

122 |

Kidney cancer (stage 4) |

0.902 |

0.870 |

0.927 |

|

123 |

Other urinary organ cancers |

0.711 |

0.656 |

0.761 |

|

124 |

Bladder cancer (stage 1) |

0.500 |

0.441 |

0.558 |

|

125 |

Bladder cancer (stage 2) |

0.623 |

0.567 |

0.676 |

|

126 |

Bladder cancer (stage 3) |

0.769 |

0.720 |

0.812 |

|

127 |

Bladder cancer (stage 4) |

0.869 |

0.830 |

0.901 |

|

128 |

Brain and nervous system cancers |

0.888 |

0.852 |

0.918 |

|

129 |

Thyroid cancer (stage 1) |

0.301 |

0.248 |

0.359 |

|

130 |

Thyroid cancer (stage 2) |

0.484 |

0.425 |

0.543 |

|

131 |

Thyroid cancer (stage 3) |

0.639 |

0.583 |

0.691 |

|

132 |

Thyroid cancer (stage 4) |

0.779 |

0.730 |

0.822 |

|

133 |

Hodgkin's disease |

0.670 |

0.612 |

0.725 |

|

134 |

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

0.689 |

0.636 |

0.737 |

|

135 |

Multiple myeloma |

0.764 |

0.714 |

0.808 |

|

136 |

Leukemia |

0.812 |

0.765 |

0.854 |

|

137 |

Bone and connective tissue cancer |

0.765 |

0.717 |

0.809 |

|

138 |

Benign neoplasm of brain and other parts of central nervous system |

0.505 |

0.442 |

0.567 |

|

139 |

Rheumatic heart disease |

0.600 |

0.542 |

0.657 |

|

140 |

Ischemic heart disease |

0.534 |

0.475 |

0.592 |

|

141 |

Ischemic stroke (mild) |

0.540 |

0.477 |

0.601 |

|

142 |

Ischemic stroke (moderate) |

0.787 |

0.740 |

0.828 |

|

143 |

Ischemic stroke (severe) |

0.840 |

0.799 |

0.875 |

|

144 |

Hemorrhagic and other non-ischemic stroke |

0.785 |

0.738 |

0.825 |

|

145 |

Hypertensive heart disease |

0.502 |

0.444 |

0.560 |

|

146 |

Cardiomyopathy and myocarditis |

0.717 |

0.661 |

0.768 |

|

147 |

Atrial fibrillation and flutter |

0.584 |

0.526 |

0.641 |

|

148 |

Aortic aneurysm |

0.647 |

0.591 |

0.700 |

|

149 |

Peripheral vascular disease |

0.430 |

0.368 |

0.492 |

|

150 |

Endocarditis |

0.646 |

0.589 |

0.700 |

|

151 |

Hermorrhoid |

0.139 |

0.103 |

0.182 |

|

152 |

Varicose veins of lower extremities |

0.173 |

0.132 |

0.219 |

|

153 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (mild) |

0.408 |

0.351 |

0.466 |

|

154 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (moderate) |

0.703 |

0.648 |

0.754 |

|

155 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (severe) |

0.722 |

0.668 |

0.771 |

|

156 |

Pneumoconiosis |

0.669 |

0.614 |

0.721 |

|

157 |

Asthma |

0.396 |

0.337 |

0.458 |

|

158 |

Interstitial lung disease and pulmonary sarcoidosis |

0.678 |

0.623 |

0.729 |

|

159 |

Cirrhosis of the liver secondary to hepatitis B |

0.707 |

0.655 |

0.755 |

|

160 |

Cirrhosis of the liver secondary to hepatitis C |

0.706 |

0.653 |

0.754 |

|

161 |

Cirrhosis of the liver secondary to alcohol use (mild) |

0.484 |

0.424 |

0.543 |

|

162 |

Cirrhosis of the liver secondary to alcohol use (moderate) |

0.668 |

0.612 |

0.722 |

|

163 |

Cirrhosis of the liver secondary to alcohol use (severe) |

0.717 |

0.664 |

0.765 |

|

164 |

Peptic ulcer disease |

0.260 |

0.207 |

0.319 |

|

165 |

Gastritis and duodenitis |

0.144 |

0.107 |

0.187 |

|

166 |

Appendicitis |

0.245 |

0.196 |

0.300 |

|

167 |

Paralytic ileus and intestinal obstruction without hernia |

0.388 |

0.332 |

0.446 |

|

168 |

Inguinal or femoral hernia |

0.269 |

0.220 |

0.322 |

|

169 |

Crohn's disease |

0.597 |

0.538 |

0.653 |

|

170 |

Ulcerative colitis |

0.545 |

0.485 |

0.604 |

|

171 |

Vascular disorders of intestine |

0.515 |

0.455 |

0.573 |

|

172 |

Gallbladder and bile duct disease |

0.448 |

0.386 |

0.511 |

|

173 |

Pancreatitis |

0.498 |

0.436 |

0.559 |

|

174 |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

0.163 |

0.123 |

0.209 |

|

175 |

Alzheimer's disease and other dementias |

0.736 |

0.685 |

0.782 |

|

176 |

Parkinson's disease |

0.660 |

0.606 |

0.711 |

|

177 |

Epilepsy |

0.581 |

0.523 |

0.637 |

|

178 |

Multiple sclerosis |

0.693 |

0.640 |

0.742 |

|

179 |

Migraine |

0.190 |

0.148 |

0.237 |

|

180 |

Tension-type headache |

0.163 |

0.121 |

0.212 |

|

181 |

Schizophrenia |

0.666 |

0.612 |

0.717 |

|

182 |

Alcohol use disorders |

0.350 |

0.295 |

0.407 |

|

183 |

Opioid use disorders |

0.457 |

0.398 |

0.517 |

|

184 |

Cocaine use disorders |

0.459 |

0.401 |

0.518 |

|

185 |

Amphetamine use disorders |

0.473 |

0.413 |

0.534 |

|

186 |

Cannabis use disorders |

0.355 |

0.299 |

0.413 |

|

187 |

Major depressive disorder (mild) |

0.279 |

0.229 |

0.333 |

|

188 |

Major depressive disorder (moderate) |

0.528 |

0.469 |

0.586 |

|

189 |

Major depressive disorder (severe) |

0.569 |

0.509 |

0.627 |

|

190 |

Dysthymia |

0.188 |

0.145 |

0.238 |

|

191 |

Bipolar affective disorder |

0.483 |

0.424 |

0.542 |

|

192 |

Panic disorder |

0.391 |

0.335 |

0.448 |

|

193 |

Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

0.321 |

0.266 |

0.378 |

|

194 |

Post-traumatic stress disorder |

0.415 |

0.357 |

0.474 |

|

195 |

Anorexia nervosa |

0.420 |

0.363 |

0.478 |

|

196 |

Bulimia nervosa |

0.392 |

0.334 |

0.451 |

|

197 |

Autism |

0.510 |

0.449 |

0.570 |

|

198 |

Asperger's syndrome |

0.408 |

0.349 |

0.469 |

|

199 |

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

0.249 |

0.200 |

0.302 |

|

200 |

Conduct disorder |

0.275 |

0.224 |

0.331 |

|

201 |

Idiopathic intellectual disability |

0.483 |

0.422 |

0.543 |

|

202 |

Borderline personality disorder |

0.397 |

0.340 |

0.455 |

|

203 |

Diabetes mellitus without complications |

0.334 |

0.279 |

0.391 |

|

204 |

Diabetes mellitus with complications |

0.663 |

0.605 |

0.717 |

|

205 |

Acute glomerulonephritis |

0.420 |

0.362 |

0.480 |

|

206 |

Chronic kidney disease due to diabetes mellitus |

0.674 |

0.617 |

0.727 |

|

207 |

Chronic kidney disease due to hypertension |

0.594 |

0.534 |

0.652 |

|

208 |

Tubulointerstitial nephritis, pyelonephritis, and urinary tract infections |

0.359 |

0.302 |

0.418 |

|

209 |

Urolithiasis |

0.294 |

0.242 |

0.350 |

|

210 |

Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

0.207 |

0.161 |

0.259 |

|

211 |

Men infertility |

0.332 |

0.279 |

0.389 |

|

212 |

Urinary incontinence |

0.287 |

0.233 |

0.345 |

|

213 |

Uterine fibroids |

0.223 |

0.177 |

0.274 |

|

214 |

Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

0.399 |

0.342 |

0.458 |

|

215 |

Women infertility |

0.362 |

0.306 |

0.421 |

|

216 |

Endometriosis |

0.349 |

0.292 |

0.408 |

|

217 |

Genital prolapse |

0.404 |

0.338 |

0.471 |

|

218 |

Premenstrual syndrome |

0.136 |

0.101 |

0.179 |

|

219 |

Thalassemias |

0.485 |

0.425 |

0.545 |

|

220 |

Sickle cell disorders |

0.552 |

0.494 |

0.609 |

|

221 |

G6PD deficiency |

0.519 |

0.458 |

0.580 |

|

222 |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

0.451 |

0.392 |

0.510 |

|

223 |

Osteoarthritis (mild) |

0.216 |

0.171 |

0.268 |

|

224 |

Osteoarthritis (moderate) |

0.415 |

0.357 |

0.474 |

|

225 |

Osteoarthritis (severe) |

0.575 |

0.515 |

0.633 |

|

226 |

Low back pain (mild) |

0.138 |

0.101 |

0.181 |

|

227 |

Low back pain (moderate) |

0.310 |

0.257 |

0.368 |

|

228 |

Low back pain (severe) |

0.456 |

0.396 |

0.517 |

|

229 |

Neck pain |

0.133 |

0.097 |

0.177 |

|

230 |

Gout |

0.390 |

0.332 |

0.451 |

|

231 |

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

0.594 |

0.533 |

0.651 |

|

232 |

Neural tube defects |

0.782 |

0.734 |

0.825 |

|

233 |

Congenital heart anomalies |

0.679 |

0.622 |

0.731 |

|

234 |

Cleft lip and cleft palate |

0.313 |

0.258 |

0.372 |

|

235 |

Down's syndrome |

0.590 |

0.533 |

0.645 |

|

236 |

Eczema |

0.135 |

0.098 |

0.179 |

|

237 |

Psoriasis |

0.235 |

0.187 |

0.288 |

|

238 |

Cellulitis |

0.273 |

0.222 |

0.329 |

|

239 |

Abscess, impetigo, and other bacterial skin diseases |

0.267 |

0.215 |

0.324 |

|

240 |

Scabies |

0.194 |

0.150 |

0.245 |

|

241 |

Fungal skin diseases |

0.260 |

0.210 |

0.316 |

|

242 |

Viral skin diseases |

0.166 |

0.126 |

0.212 |

|

243 |

Acne vulgaris |

0.049 |

0.029 |

0.078 |

|

244 |

Alopecia areata |

0.154 |

0.114 |

0.200 |

|

245 |

Pruritus |

0.100 |

0.069 |

0.140 |

|

246 |

Urticaria |

0.106 |

0.074 |

0.147 |

|

247 |

Decubitus ulcer |

0.479 |

0.421 |

0.536 |

|

248 |

Glaucoma |

0.449 |

0.388 |

0.510 |

|

249 |

Cataracts |

0.324 |

0.267 |

0.383 |

|

250 |

Macular degeneration |

0.457 |

0.396 |

0.518 |

|

251 |

Refraction and accommodation disorders |

0.206 |

0.162 |

0.257 |

|

252 |

Dental caries |

0.065 |

0.042 |

0.097 |

|

253 |

Periodontal disease |

0.206 |

0.161 |

0.257 |

|

254 |

Edentulism |

0.471 |

0.410 |

0.531 |

|

255 |

Pedestrian injury by road vehicle |

0.470 |

0.410 |

0.530 |

|

256 |

Road injury (pedal cycle vehicle) |

0.315 |

0.262 |

0.371 |

|

257 |

Road injury (motorized vehicle with two wheels) |

0.495 |

0.435 |

0.555 |

|

258 |

Road injury (motorized vehicle with three or more wheels) |

0.597 |

0.538 |

0.653 |

|

259 |

Falls |

0.165 |

0.126 |

0.212 |

|

260 |

Drowning |

0.514 |

0.454 |

0.573 |

|

261 |

Fire, heat and hot substances |

0.362 |

0.304 |

0.423 |

|

262 |

Poisonings |

0.475 |

0.415 |

0.536 |

|

263 |

Mechanical forces (firearm) |

0.547 |

0.485 |

0.608 |

|

264 |

Adverse effects of medical treatment |

0.362 |

0.306 |

0.420 |

|

265 |

Animal contact (venomous) |

0.363 |

0.304 |

0.424 |

|

266 |

Animal contact (non-venomous) |

0.132 |

0.095 |

0.176 |

|

267 |

Self-harm |

0.516 |

0.455 |

0.577 |

|

268 |

Assault by firearm |

0.488 |

0.429 |

0.548 |

|

269 |

Assault by sharp object |

0.260 |

0.212 |

0.312 |

|

270 |

Exposure to forces of nature |

0.235 |

0.188 |

0.287 |

|

271 |

Collective violence and legal intervention |

0.432 |

0.373 |

0.492 |

|

272 |

Allergic rhinitis |

0.087 |

0.059 |

0.123 |

|

273 |

Atopic dermatitis |

0.231 |

0.182 |

0.285 |

|

274 |

Metabolic syndrome |

0.304 |

0.250 |

0.361 |

|

275 |

Allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis |

0.166 |

0.124 |

0.215 |

|

276 |

Diabetes mellitus and osteoarthritis |

0.495 |

0.436 |

0.553 |

|

277 |

Allergic rhinitis and asthma |

0.187 |

0.145 |

0.236 |

|

278 |

Allergic rhinitis and osteoarthritis |

0.192 |

0.147 |

0.244 |

|

279 |

Allergic rhinitis and major depressive disorder |

0.394 |

0.336 |

0.453 |

|

280 |

Major depressive disorder and osteoarthritis |

0.478 |

0.418 |

0.539 |

|

281 |

Diabetes mellitus and ischemic stroke |

0.629 |

0.570 |

0.685 |

|

282 |

Diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis |

0.478 |

0.418 |

0.539 |

|

283 |

Diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, and major depressive disorder |

0.543 |

0.484 |

0.601 |

|

284 |

Diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, and ischemic stroke |

0.667 |

0.611 |

0.719 |

|

285 |

Allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis |

0.172 |

0.131 |

0.219 |

|

286 |

Diabetes, osteoarthritis, and tuberculosis |

0.574 |

0.514 |

0.632 |

|

287 |

Diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis |

0.494 |

0.431 |

0.556 |

|

288 |

Full heath |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

289 |

Being dead |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download