INTRODUCTION

The relative survival rate of cancer has reached approximately 70% in Korea with advances in diagnosis and improved treatment technologies.

1 However, the number of patients with cancer exceeds 1.6 million, and about 57% of those are between 15 and 64 years of age.

1 This population of survivors is in their working prime, but the effects of cancer treatment on employment have not been sufficiently investigated. The majority of cancer survivors have a higher rate of absence from work than the general population (e.g., 81 days for gastric cancer patients vs. 1.8 days for the general population);

2 overall, work loss owing to cancer constitutes 53%.

3 Moreover, 47% of cancer survivors lose their jobs after treatment. The work-return rate by cancer survivors is 30.5% in Korea,

4 half that of the global average of 63.5% (range, 24%–94%).

5

The implication of cancer survivors returning to jobs is vital in terms of reintegration. Many employees affected by cancer feel a profound sense of boredom and isolation during their period of sick leave, and several acknowledged that they had been diagnosed with depression.

6 Conversely, returning to work can improve the quality of life of many cancer patients. Physicians as well as occupational health service providers may contribute to a successful return to work, and can thus enhance the quality of life of cancer patients.

7

The assessment of fitness for work entails evaluating workers' abilities and health risks in relation to the working environment.

8 In other words, the goal is to ensure that workers are fit to effectively perform tasks without further risk to their health. Cancer survivors can continue to show side effects such as fatigue, lymphedema, and pain after acute treatment. Those who return to the community can adapt to their workplaces; cooperating with the ongoing communication between medical staff and workplaces to ensure that their symptoms are not aggravated. Accordingly, the assessment of fitness for work can be employed as a tool to determine efficient decision-making of cancer survivors, medical staff, and workplace managers.

8

However, many cancer survivors receive little advice from their treating physicians about return-to-work issues, and they experience a lack of guidance from their general practitioners and occupational health physicians (OHPs).

910 In fact, a large number of cancer survivors in Korea do not receive a medical evaluation before returning to work, and few studies have addressed the status of assessing fitness for work.

Therefore, in this study, we assessed cancer survivors' ability to return to work, the role of clinical care, and the current status of effective return-to-work.

DISCUSSION

The societal reintegration of cancer survivors has been increasing. A large proportion of younger and middle-aged survivors constitute a part of the workforce at the time of treatment. Thus, returning to work is an important element of social reintegration and a sign of a return to normalcy.

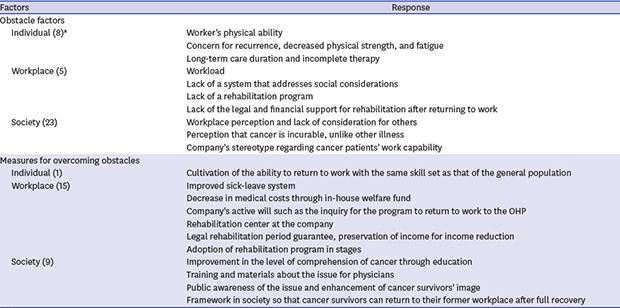

14 In this study, we identified the current status of clinical care, the relationship between cancer survivors and the workplace, obstacles from the viewpoint of OHPs, and measures for survivors' return to work.

The findings were as follows: First, only 25% of the respondents had experience caring for cancer survivors. Moreover, the assessments of fitness for work were lower for cancer (16 times) than for disorders of the musculoskeletal system (54 times). Currently, the procedures in place to help cancer survivors return to work are insufficient in Korea. Such inadequate medical practice can lead to a void in the continuity of care for cancer survivors. The Institute of Medicine had suggested that employers, legal advocates, healthcare providers, sponsors of support services, and government agencies should help eliminate discrimination and minimize the adverse effects of cancer on employment, while also supporting cancer survivors over both the short and long term.

15 Currently, cancer is considered a chronic illness in the EU and the US, and an attempt has been made to ensure cancer survivors’ return to work.

1617 For example, in a study conducted by Clark and Landis,

18 the OHP team was involved in the outpatient clinic when cancer patient care was being administered, providing a comprehensive work-reentry plan and counseling as a work-directed intervention. In work-rehabilitation research conducted by Verbeek et al.,

19 sick leave was shortened and patient satisfaction improved as a result of the OHPs' assessment of return-to-work for workers who needed vocational rehabilitation. However, in Korea, cancer practitioners decide the date for terminating the treatment of cancer survivors and only provide treatment for the recurrence of cancer or chronic disease care through a follow-up examination; they do not handle return-to-work issues. However, our results indicate that physicians should pay attention to and get involved in cancer patients' return-to-work issues to prevent a void in the continuity of care.

A total of 81.5% of the OHPs in our survey indicated duties related to being involved in cancer survivors' return-to-work in the future. The role of responsible physicians in cancer survivors' return-to-work is to influence their decision making with regard to the procedure and method of returning to their workplace and to shorten sick leave.

920 This has the potential to positively impact the relationship between the patient and the employer, while supporting the patient's safe adaptation to the work environment.

21 Physicians in charge of assessing fitness for work will need to consider specific diseases and assess their progression. From the perspective of occupational health, one may be suitable for work even if she/he has a certain disease. On the other hand, a disease that may not prevent a patient from working per se but which may indirectly affect the abilities or health of a coworker would make that patient unfit for work in that particular capacity.

22 Whether conducted by specialists in occupational medicine or other physicians, a proper examination requires a clear understanding of how to serve and protect the interests of the employee, employer, and physician.

8 Accordingly, OHPs should be prioritized as the personnel in charge of cancer survivors' healthy return to work. They should be able to play the additional role of a mediator between the physician and the employer. In the future, a domain should be established to take charge of the clinical environment based on extensive experience and discussion.

With regard to opinions on workplace managers, the lack of consideration during the rehabilitation period and when adjusting the duties of cancer patients when they return to work was pointed out. Korea still lacks a clear system for cancer survivors' return-to-work. The right to resume a job depends on the perception, knowledge, and attitude of the employees returning to work after cancer treatment.

23 Employers require training, support, and resources to help them facilitate employment and job retention among such employees.

23 With the inclusion of cancer in the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 2005

24 and the Equality Act (2010),

25 employers in the UK now have a legal responsibility to provide appropriate advice to not only employees with cancer but also those caring for a cancer patient. “The Working with Cancer Survey” reported that more than 1 in 5 employers (22%) is unaware that the DDA includes cancer as a disability and nearly three-quarters (73%) do not have a formal policy in place for managing employees affected by cancer.

26 In the future, Korea needs to clarify employers' responsibilities and roles regarding cancer survivors' return-to-work and provide training to increase knowledge and awareness regarding this matter.

OHPs in our study faced further difficulty in counseling employees who used to be cancer patients than employees with other illnesses, and the majority of OHPs were not adequately trained to communicate with cancer patients. This questions the extent to which current specialist training and continuing professional development for established OHPs can meet this important training need. The current training curriculum for occupational medicine in the UK identifies disability, rehabilitation, and chronic disease care as core competencies. Our results suggest potential areas for improvement in the knowledge base and training of OHPs in relation to these competencies and in advising cancer survivors.

13Accredited training in the Netherlands began in 2011; it consists of a 5-day theoretical module and a practical internship in an oncological center. OHP tasks can be described in terms of support and counseling on the following sub-tasks: continuing work during cancer treatment, general return-to-work, legislation on sickness and disability, intervention referral, and deliberation with the OHP and the clinical care team.

27 It is necessary to introduce the curriculum to OHPs to allow counseling for cancer patients' return to work after completing cancer treatment in Korea. Moreover, more than half of the OHPs indicated that their role was not understood by physicians from other departments, a finding that corresponded to that by Zaman

et al.27 However, Tamminga et al.

16 found that communication improved between oncologists and OHPs during support interventions and increased interdisciplinary collaboration. Hence, efforts should be made to improve multidisciplinary interventions in the clinical environment.

The obstacles in the way of cancer survivors' return-to-work include culturing their capability to return to work at the same level as that of the general public and overcoming the deficiency in the physical abilities of workers.

2829 Cancer survivors experience long-term effects of curative therapy, such as fatigue, depression, pain, and functional limitations, which can affect their confidence and self-esteem when resuming paid employment.

26 Accordingly, they will inevitably experience a decrease in work capacity after treatment. Therefore, an attempt must be made in clinical practice to counterbalance this impact through some type of intervention. Berglund et al.

30 introduced a rehabilitation program called “Starting Again,” which included training and information on coping skills delivered by oncology nurses in a 2 hours session. Purcell et al.

31 created an educational program conducted by a multidisciplinary team that uses a handbook, goal-setting sheet, and progress diary to decrease patient fatigue. The program includes follow-up telephone calls after 2 and 4 weeks to monitor and enhance the effects of training. Similar programs need to be established in Korea.

Many cancer survivors have successfully returned to work with the support of their companies. For example, Grunfeld et al.

32 surveyed 252 companies and identified ways companies help cancer survivors to return to work. These included phased returns, changes in work duties (e.g., less physical, client-facing), changes to the physical environment, and counseling and therapeutic services. Various in-company support programs are also needed to ensure that cancer survivors can return to work in a stable manner and maintain their jobs.

Improving the level of understanding of cancer through education is important to change the perception that it is an incurable disease, unlike other common illnesses. It has also been suggested that OHPs nationally promote assessments of work fitness for cancer survivors. In the last decade, increasing emphasis has been placed on including people with disabilities (including cancer) in society and the labor market. This has been encouraged by a Europe-wide movement, away from passive measures to more active ones, and has been achieved by implementing legislation including obligatory employment quota schemes, anti-discrimination laws, job-protection rights, and targeted labor-market policies.

33 Because cancer survivors are also members of society, they need to be provided with social support and alternatives for reintegration, and there is a need to create an environment for them to work along with the general public.

This study had some limitations. First, it has a selection bias because of the low response rate, thereby making it difficult to generalize the results. It is necessary to determine how to increase the response rate by conducting a mail questionnaire survey 2 or more times to determine the views of non-responders. Second, it is difficult to prove the validity of the results because no validated questionnaire has been developed for OHPs in Korea. Therefore, this method should be adopted only in preliminary research.

Despite these limitations, this study identified the current status of clinical care, from the OHPs' perspective, for cancer survivors' return to work, the current status of the association between cancer survivors and workplace, and the obstacles they face. Thus, this study is considered meaningful as a basic preliminary study to assess the fitness of cancer survivors returning to work and to outline the role of OHPs in the future.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download