This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Orthodontic treatment is more complicated when both soft and hard tissues must be considered because an impacted maxillary canine has important effects on function and esthetics. Compared with extraction of impacted maxillary canines, exposure followed by orthodontic traction can improve esthetics and better protect the patient's teeth and alveolar bone. Therefore, in order to achieve desirable tooth movement with minimal unexpected complications, a precise diagnosis is indispensable to establish an effective and efficient force system. In this report, we describe the case of a 31-year-old patient who had a labio-palatal horizontally impacted maxillary left canine with a severe occlusal alveolar bone defect and a missing maxillary left first premolar. Herein, with the aid of three-dimensional imaging, sequential traction was performed with a three-directional force device that finally achieved acceptable occlusion by bringing the horizontally impacted maxillary left canine into alignment. The maxillary left canine had normal gingival contours and was surrounded by a substantial amount of regenerated alveolar bone. The 1-year follow-up stability assessment demonstrated that the esthetic and functional outcomes were successful.

Keywords: Sequential traction, Custom design, Three-directional force, Impaction

INTRODUCTION

The maxillary canines are important for function and esthetics. Except for the third molars, the most frequently impacted teeth are the maxillary permanent canines, with an incidence ranging from 0.8% to 2.8%.

12 Among these canine impactions, 85% are palatal and 15% are buccal.

3 In the present case, the horizontally impacted maxillary canine crown and root were palatal and buccal, respectively, which has been rarely reported. Moreover, only gingival tissue was present without alveolar bone occlusal to the impacted canine, which might be due to the lack of long-term occlusal force stimulation.

In general, there are five options to manage impacted canines: (1) no active treatment, (2) interceptive treatment, (3) surgical exposure and orthodontic alignment, (4) extraction, and (5) surgical repositioning.

4 In this case, extraction was thought to be the simplest treatment. However, extraction of the impacted canine would have worsened the depression of the left angulus oris. The maxillary ipsilateral first premolar was absent. Hence, surgical exposure with orthodontic traction was the only remaining choice. Nevertheless, traction was extremely likely to cause resorption of the adjacent teeth roots and could fail because of its complicated location. Hence, consideration of both the custom design and sequential traction with the help of three-dimensional (3D) treatment planning was critical to determine the most optimal traction path, which is important for effective and efficient traction.

The purpose of this report is to describe the treatment and management of an adult with a horizontally impacted maxillary left canine and an absent maxillary left first premolar using a three-directional force approach. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and the accompanying images.

DIAGNOSIS AND ETIOLOGY

A 31-year-old man visited our hospital with a chief complaint of dental crowding and an inappropriate removable partial denture in his left maxillary edentulous region. His maxillary left canine was impacted and the ipsilateral first premolar had been extracted because of severe dental caries.

The initial extraoral photographs show a slight convex profile with depression of the left angulus oris and a relatively symmetrical face (

Figure 1). The intraoral examination indicated a bilateral Angle Class II molar relationship with an impacted maxillary left canine and an absent maxillary left first premolar. The upper midline was deviated 2 mm to the patient's left and the lower midline was deviated 1 mm to the patient's left. The overjet was 4.4 mm, and the overbite was 1.3 mm. Both the maxillary and mandibular arches showed severe crowding. Crossbite of the maxillary right lateral incisor was observed and the maxillary left second molar demonstrated a scissor bite with the mandibular left second molar (

Figures 1 and

2). The left maxillary edentulous region had been restored with a removable partial denture; inflammation of the mucous membrane was still visible in the edentulous region.

A panoramic radiograph analysis displayed a horizontally impacted left maxillary canine and mesioangular impacted mandibular third molars (

Figure 3). Furthermore, there was no alveolar bone occlusal to the impacted maxillary left canine.

To locate the impacted left maxillary canine precisely, a 3D computed tomography rendering was analyzed, which simplifies observation through visualization of the relationship between the canine and adjacent teeth (

Figure 4). According to the 3D image, the canine's crown was palatally close to the root apex of the left maxillary lateral incisor and the canine's root apex was buccally close to the root apex of the left maxillary second premolar.

The cephalometric analysis exhibits a slight skeletal Class II malocclusion with mild mandibular hypoplasia, slight retroclination of the maxillary incisors, and normal inclination of the mandibular incisors (

Figures 3 and

5,

Table 1).

TREATMENT OBJECTIVES

The treatment objectives for the present patient were as follows: (1) relocate the impacted maxillary left canine and bring it into alignment, (2) relieve the crowding in the maxillary and mandibular arches, (3) correct the maxillary right lateral incisor crossbite, (4) correct the maxillary left second molar and mandibular left second molar scissor bite, (5) achieve bilateral Class I molar and canine relationships, (6) align the midlines, and (7) improve the facial esthetics, especially the depression of the left angulus oris.

TREATMENT ALTERNATIVES

There were four treatment alternatives as follows.

1. Extraction of the maxillary right first premolar, mandibular right first premolar, and mandibular left second premolar while retaining the submerged maxillary left canine. Extraction would be followed by restoration with a porcelain bridge or removable partial denture after completing the orthodontic treatment. There are several potential sequelae of an impacted canine such as internal resorption of the impacted tooth, external resorption of adjacent or impacted teeth, infection and migration of adjacent teeth, cyst formation, and ankylosis.5

2. Extraction of the impacted canine, maxillary right first premolar, mandibular right first premolar, and mandibular left second premolar. However, after the impacted maxillary left canine is extracted, the potential results might include tooth loosening or an increased likelihood of maxillary left lateral incisor extraction due to a lack of support from the alveolar bone. Therefore, restoration with a porcelain bridge or implants would be possible after orthodontic treatment. However, alveolar bone resorption would hinder the subsequent implant restoration.

-

3. Relocation of the impacted canine through extraction followed by autotransplantation. Next, the maxillary right first premolar, mandibular right first premolar, and mandibular left second premolar would be extracted. However, the autotransplantation of teeth might lead to ankylosis, progressive root resorption, and failed development of the surrounding alveolar bone.6

In this patient, the insufficient alveolar bone increased the difficulty of autotransplantation of the horizontally impacted canine. Moreover, autotransplantation would increase the risk of damage to the periodontal ligament and root during removal.

67

-

4. An attempt to perform traction on the impacted maxillary left canine while maintaining the maxillary right first premolar, mandibular right first premolar, and mandibular left second premolar without initial extraction. However, if the impacted canine displays a favorable response to the treatment, extraction of the premolars would be performed.

According to the above analysis, orthodontic relocation of the impacted maxillary left canine was the preferred option.

Treatment plan

The treatment plan consisted of three stages (

Figure 6). First, a custom device was designed for traction of the impacted maxillary left canine. Second, sequential extraction of the maxillary and mandibular premolars was planned (at different times). Third, fine adjustment with a straight archwire technique would be performed to achieve an optimal occlusal relationship.

In the first phase, a custom device with three arms was fabricated to perform traction on the impacted maxillary left canine. These arms were designed to produce forces in the occlusal, distal, and buccal directions (

Figure 7). Moreover, the closed-eruption technique was used to bond a bracket to the impacted maxillary left canine. First, the occlusal arm (Ao) applied an occlusal force (Fo) to cause coronal occlusal movement of the maxillary left canine, moving the crown of the canine away from the root of the maxillary left lateral incisor and intruding the canine's root into the alveolar bone (

Figure 8A). Next, the distal arm (Ad) applied a distal force (Fd) to rotate the impacted maxillary left canine counterclockwise in the horizontal plane and make its crown distal (

Figure 8B). Finally, the buccal arm (Ab) applied a buccal force (Fb) to create counterclockwise rotation in the sagittal plane to upright the impacted maxillary left canine (

Figure 8C).

In the second phase, the mandibular right first premolar and contralateral second premolar were extracted. Then, the maxillary right first premolar would be extracted if the impacted canine responded favorably to treatment. Otherwise, extraction of the impacted maxillary left canine and a corresponding restoration would be considered.

In the third phase, an inverted maxillary canine bracket was bonded to the maxillary left canine, which changed the torque from −7° to +7° to produce extra torque for fine adjustment (

Figure 9).

TREATMENT PROGRESS

Treatment began using a closed-eruption technique to bond a bracket to the maxillary left canine, in which the depth of impaction, anatomy of the edentulous site, direction of the teeth, and type of orthodontic force were crucial considerations in deciding the exposure method.

89 A custom device with three arms was fabricated to provide traction in different directions (

Figure 7). According to the figure, Ao applies an Fo, which leads to coronal occlusal movement of the maxillary left canine (

Figure 10). Two months later, a Fd applied by Ad was designed to pull the canine's crown distally (

Figure 11). A Fb applied by Ab was designed to pull the impacted canine's crown buccally at 13 months (

Figure 12).

At 10 months, after extraction of the mandibular right first premolar and left second premolar, brackets were placed on all mandibular teeth for primary alignment and leveling (

Figure 13).

At 16 months, a helix was added to correct the scissor bite of the maxillary and mandibular left second molars (

Figure 14). Then, the maxillary left third molar was extracted.

At 22 months, the traction device was removed after the maxillary left canine appeared in the arch. The brackets were bonded to all maxillary teeth after the maxillary right first premolar was extracted (

Figure 15). In addition, an inverted maxillary canine bracket was bonded to the maxillary left canine to achieve extra torque.

Throughout the treatment, alignment and leveling were performed by using 0.014-inches (in) and 0.016-in nickel-titanium archwires sequentially, followed by rectangular nickel-titanium archwires (0.016 × 0.022 in, 0.017 × 0.025 in, and 0.019 × 0.025 in). Finally, 0.019-in × 0.025-in stainless steel archwires were used for fine adjustment.

The patient's treatment was interrupted for about 2 years because of a car accident. At 56 months, all brackets were removed and vacuum-formed retainers were delivered to maintain the tooth positions. After treatment, dental casts, photographs, and cephalometric and panoramic radiographs were collected.

RESULTS

The impacted canine was in the proper position in the maxillary arch with proper support from periodontal tissue, while the normal gingival contours had an adequate width of keratinized attached gingiva (

Figure 16). The facial esthetics were also improved, especially the depression of the left angulus oris was less evident (

Figure 17). The anterior crossbite and posterior scissor bite had been corrected. A bilateral Class I occlusion with improved overjet and overbite was achieved and the midlines matched the facial midline (

Figures 16 and

18). A panoramic radiograph exhibited favorable root alignment; the root of the maxillary left canine was surrounded by substantially regenerated alveolar bone, while the roots of the maxillary right lateral and center incisors had some resorption, which may be due to the extended duration of orthodontic treatment, intrusion and bodily movement of the teeth, and genetic factors (

Figures 19,

20,

21).

1011121314 The maxillary left third molar was extracted for correction of the scissor bite of the maxillary and mandibular left second molar. The patient refused maxillary right third molar and mandibular third molar extractions despite our recommendation. A lateral cephalometric radiograph superimposition indicates the maintained profile (

Figures 22,

23,

24).

The post-treatment cephalometric analysis showed that the Class II skeletal relationship was maintained and the overjet and overbite relationships were improved. After removal of the fixed appliances, vacuum-formed retainers were applied to the maxillary and mandibular teeth to maintain their positions. After 1 year of treatment, the esthetics and dental occlusion of the patient were stable without additional morphological changes to the apical root (

Figure 25).

DISCUSSION

An impacted maxillary canine is a common challenge in orthodontics treatment, as the development of the maxillary canines from formation to final full occlusion is the longest and most flexural.

15 Moreover, the maxillary canine is an excellent abutment for fixed and removable prostheses and is crucial for esthetics. For these reasons, the maxillary canine is also called the “cornerstone of the maxillary arch,” and its removal should be strictly avoided.

Orthodontic treatment for horizontally impacted canines is likely to have a poor prognosis because of the difficulty of orthodontic traction and unexpected effects on periodontal health.

16 It is important to ensure that the patient understands the risks of the recommended treatment, such as a loss of periodontal support, resorption of the apical roots of the canine and adjacent teeth, loss of tooth vitality, ankylosis, and a long treatment duration.

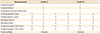

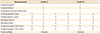

In this patient, the canine was impacted labio-palatally and horizontally and in close proximity to adjacent tooth roots; thus, it was almost impossible to replace the maxillary left canine with the maxillary left second premolar, as the maxillary left first premolar was absent and extraction of the canine might cause undesirable alveolar bone loss. Given this rare and complicated situation, a custom-designed device was fabricated that applied Fo, Fd, and Fb for sequential traction to determine the most optimal traction path for the impacted canine. Moreover, the 3D force system applied by the custom force device changed the axis of the tooth in a stepwise manner and prevented the tooth from moving toward adjacent tooth roots during displacement. These successful results were attributed to the adequate custom design of the 3D force system and proper sequential traction. We used the closed-eruption technique. This technique resulted in the left maxillary canine with a good periodontal attachment level, which was similar to that of the contralateral right maxillary canine (

Table 2).

Orthodontic traction was chosen as the optimal treatment for the patient as opposed to extraction, which greatly increases the risk of periodontal breakdown and infrabony defects. Although infrabony defects after extraction of the impacted canine might be treated through vertical bone augmentation techniques such as distraction osteogenesis, onlay bone grafting, and guided bone regeneration, regaining the alveolar bone height, which is in the range of millimeters, the amount might be undetectable.

17 Through orthodontic traction, the tooth movement induced bone formation from periodontal cells, which was an efficient way to regenerate bone at the defect.

18 In this patient, satisfactory periodontal tissue was achieved and an appropriate alveolar bone height was maintained.

In addition to the difficulties of orthodontic traction, torque correction of impacted canines remain challenging. In this case, we inverted the maxillary canine bracket to produce additional torque when bringing the maxillary left canine into alignment. Although the palatal tissue coverage of the maxillary left canine was sufficient, when viewing the canine buccally, the clinical crown appeared slightly longer because of a lack of buccal bone support.

Overall, a precise diagnosis, appropriate force system with the aid of 3D rendering, and a comprehensive and detailed treatment plan contributed to a satisfactory clinical outcome for this patient.

CONCLUSION

Treatment of a labio-palatal horizontally impacted maxillary canine was a clinical challenge, especially since it was very close to adjacent teeth with insufficient surrounding alveolar bone. In this case, the closed-eruption technique and sequential traction with custom-designed three-directional orthodontic forces were critical to bringing the tooth into occlusion successfully.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Pretreatment extraoral and intraoral photographs. A removable partial denture is in the left maxillary edentulous region.

Figure 2

Pretreatment dental casts.

Figure 3

A pretreatment panoramic radiograph.

Figure 4

A, Pretreatment axial computed tomography images of the impacted left maxillary canine. B and C, Pretreatment three-dimensional reconstructed computed tomography images of the impacted left maxillary canine are shown in yellow.

Figure 5

A pretreatment cephalometric radiograph (A) and cephalometric tracing (B).

Figure 6

The proposed treatment procedure for the impacted maxillary canine in this case.

Ao, Occlusal arm; Fo, occlusal force; Ad, distal arm; Fd, distal force; Ab, buccal arm; Fb, buccal force.

Figure 7

The custom-designed device with three arms (Ao, Ad, and Ab) was implemented on the cast model.

Ao, Occlusal arm; Ad, distal arm; Ab, buccal arm.

Figure 8

Biomechanics of the custom traction device. A, Occlusal direction; B, distal direction; C, buccal direction.

Cres, Center of resistance; Fo, occlusal force; Fd, distal force; Fb, buccal force.

Figure 9

The bracket was inverted and bonded to the maxillary left canine to apply additional torque.

Figure 10

Traction of the maxillary left canine in the occlusal direction. The occlusal arm (Ao) applies an occlusal force (Fo). A, Before activation; B, activation procedure using weingart plier; C, activation by connecting the Ao and the impacted tooth.

Figure 11

Traction of the maxillary canine in the distal direction. The distal arm (Ad) applies a distal force (Fd).

Figure 12

Traction of the maxillary canine in the buccal direction. The buccal arm (Ab) applies a buccal force (Fb).

Figure 13

Intraoral photographs obtained at 10 months. The alignment and leveling on the mandibualr arch have commenced.

Figure 14

A helix was added to correct the scissor bite of the maxillary left second molar and mandibular left second molar.

Figure 15

Intraoral photographs obtained at 22 months. The alignment and leveling on the maxillary arch have commenced.

Figure 16

Post-treatment extraoral and intraoral photographs.

Figure 17

Pretreatment and post-treatment smile photographs.

Figure 18

Post-treatment dental casts.

Figure 19

A post-treatment panoramic radiograph.

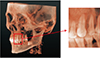

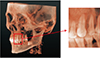

Figure 20

Three-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography images.

Figure 21

Pretreatment (white) and post-treatment (red) superimposed three-dimensional images of the dentition. The impacted left maxillary canine is shown in yellow.

Figure 22

A post-treatment cephalometric radiograph.

Figure 23

A post-treatment cephalometric tracing.

Figure 24

A superimposition of pretreatment (black lines) and post-treatment (red lines) cephalometric tracings.

Figure 25

One-year retention is shown in extraoral and intraoral photographs.

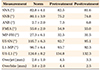

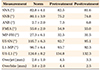

Table 1

Cephalometric analyses before and after treatment

Table 2

The periodontal measurements of the maxillary right and left canines

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC [81371121 and 81570950]), Shanghai Summit & Plateau Disciplines, the “Chen Xing” project from Shanghai Jiaotong University.

We thank Xiaoyi Lou for modifications and Jie Zhang for making the figures.

References

1. Grover PS, Lorton L. The incidence of unerupted permanent teeth and related clinical cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985; 59:420–425.

2. Aydin U, Yilmaz HH, Yildirim D. Incidence of canine impaction and transmigration in a patient population. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004; 33:164–169.

3. Hitchin AD. The impacted maxillary canine. Br Dent J. 1956; 100:1–14.

4. Counihan K, Al-Awadhi EA, Butler J. Guidelines for the assessment of the impacted maxillary canine. Dent Update. 2013; 40:770–772. 775–777.

5. Bishara SE. Impacted maxillary canines: a review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992; 101:159–171.

6. Gonnissen H, Politis C, Schepers S, Lambrichts I, Vrielinck L, Sun Y, et al. Long-term success and survival rates of autogenously transplanted canines. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010; 110:570–578.

7. Kim E, Jung JY, Cha IH, Kum KY, Lee SJ. Evaluation of the prognosis and causes of failure in 182 cases of autogenous tooth transplantation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005; 100:112–119.

8. Kokich VG. Surgical and orthodontic management of impacted maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004; 126:278–283.

9. Kaczor-Urbanowicz K, Zadurska M, Czochrowska E. Impacted teeth: an interdisciplinary perspective. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2016; 25:575–585.

11. Mirabella AD, Artun J. Risk factors for apical root resorption of maxillary anterior teeth in adult orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995; 108:48–55.

12. Krishnan V. Root resorption with orthodontic mechanics: pertinent areas revisited. Aust Dent J. 2017; 62:Suppl 1. 71–77.

13. Nieto-Nieto N, Solano JE, Yañez-Vico R. External apical root resorption concurrent with orthodontic forces: the genetic influence. Acta Odontol Scand. 2017; 75:280–287.

14. Al-Qawasmi RA, Hartsfield JK Jr, Everett ET, Flury L, Liu L, Foroud TM, et al. Genetic predisposition to external apical root resorption in orthodontic patients: linkage of chromosome-18 marker. J Dent Res. 2003; 82:356–360.

15. Dewel BF. The upper cuspid: its development and impaction. Angle Orthod. 1949; 19:79–90.

16. Botticelli S, Verna C, Cattaneo PM, Heidmann J, Melsen B. Two-versus three-dimensional imaging in subjects with unerupted maxillary canines. Eur J Orthod. 2011; 33:344–349.

17. Khojasteh A, Morad G, Behnia H. Clinical importance of recipient site characteristics for vertical ridge augmentation: a systematic review of literature and proposal of a classification. J Oral Implantol. 2013; 39:386–398.

18. Lindskog-Stokland B, Wennström JL, Nyman S, Thilander B. Orthodontic tooth movement into edentulous areas with reduced bone height. An experimental study in the dog. Eur J Orthod. 1993; 15:89–96.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download