Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is one of the most common benign tumors of the liver. There is still a lack of evidence on surgical indications for FNH. This study intended to analyze the surgical indications for FNH.

Results

Common reasons leading to surgical resection were diagnostic uncertainty (n=31), and persistent symptoms (n=8). None of our patients had a past history of contraceptive use. Percutaneous biopsy was performed in 14 patients and FNH was diagnosed in nine patients, and hepatic adenoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, plasmacytoma, angiosarcoma, and atypical hepatocellular proliferation in one patient each. Minor hepatectomy (n=37) was performed more frequently than major hepatectomy (n=11). Open hepatectomy (n=29) was performed more frequently than laparoscopic hepatectomy (n=19), but laparoscopic and minimally-invasive surgery was frequently performed during the late phase of the study period. Postoperative surgical complications occurred in two patients (4.1%).

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is one of the most common benign tumors of the liver. Hyperplastic nodules and stellate central scars are characteristic. It is not known to progress to malignancy. It is known to be associated with antihormonal therapy and contraceptive use, but conclusive evidence is still lacking. It may cause epigastric pain and discomfort, but it is often asymptomatic. Thus FNH is often found incidentally on health screening. If symptoms are present, appropriate conservative treatment should be performed. Surgical resection can be considered if symptoms persist or if imaging findings are difficult to distinguish from other diseases requiring surgical treatment. Because there are no reports of FNH transformation to malignancy, it is important to determine the indication for surgical resection.123456

The aim of this study was to analyze the surgical indications and postoperative outcomes of FNH.

The liver resection database of our institution was queried to identify patients who underwent primary surgical treatment for FNH during the 11 years between January 2005 and December 2015.7 The Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center approved this study.

This study was performed as a retrospective observational study. Patients were followed by institutional medical records review and the assistance of the National Health Insurance Service until September 2018. Data were collected on age, gender, contraceptive use, comorbid liver diseases, initial hospital visits, preoperative examination/diagnosis, surgical indications, operative procedures, postoperative outcomes, and pathologic findings.

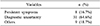

Profiles of the 48 patients are summarized in Table 1. Interestingly, none of our patients had a past history of contraceptive use. The reasons for the first imaging study were regular check-up (n=23), presence of symptoms (n=18), routine cancer surveillance (n=4), and abnormal liver function tests (n=3).

Ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used for diagnosis of liver mass at our institution. In our patients, US, CT, and MRI were performed in 51%, 100%, and 90% of patients, respectively.

Percutaneous biopsy was performed in 14 patients. Of them, nine were diagnosed with FNH, and the other patients were diagnosed with hepatic adenoma (n=1), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (n=1), plasmacytoma (n=1), angiosarcoma (n=1), and atypical hepatocellular proliferation (n=1).

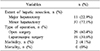

The reasons surgery was performed are summarized in Table 2. Diagnostic uncertainty (n=31) was the most common reason for surgical resection. First, FNH was suspected on imaging studies, but if other diseases requiring surgical treatment could not be excluded, such as hepatic adenoma and HCC, these patients underwent surgical treatment. Second, surgical treatment was performed on patients initially suspected to have diseases other than FNH, such as metastatic liver tumors and paraganglioma. Third, patients who had percutaneous biopsy findings of plasmacytoma, angiosarcoma (Fig. 1), or HCC underwent surgical treatment.

Eight patients underwent surgical treatment due to persistent abdominal pain or discomfort, despite conservative treatment, in whom the tumors were greater than 4 cm.

Continuously-growing tumor on follow-up was one of the common reasons for surgical treatment (n=5, Fig. 2). Three patients requested surgery, rather than prolonged observation. Surgical treatment was preferred in young patients (≤35 years of age) with large-sized masses (≥7 cm in maximal diameter). A young woman planning to become pregnant underwent surgery because of suspicion of hepatic adenoma, as well as FNH, in preoperative imaging studies (Table 2).

Minor hepatectomy (n=37) was performed more frequently than major hepatectomy (n=11). Open hepatectomy (n=29) was performed more frequently than laparoscopic hepatectomy (n=19), but a laparoscopic approach and minimally-invasive surgery were preferred during the late phase of the study period, compared to the early phase.

Postoperative complications developed in two patients. In one patient a minor bile leak developed, and in the other patient, fluid collected at the cut liver surface. There was no mortality among patients in this study (Table 3).

The median size of the tumor was 3.9 cm (range: 0.7–15). Forty-four patients had a single tumor and four patients had two. Three patients had small masses <1 cm in diameter and underwent surgical treatment due to malignancy risk. Locations of the tumors were the right lobe in 16 patients, left lobe in 26, caudate lobe in four and bilateral in two patients.

Two patients showed concurrent pathology of hepatic adenoma (n=1) and angiosarcoma (n=1), which were the same as the preoperative percutaneous biopsy findings.

FNH of the liver is a benign lesion occurring in 0.6 to 3% of the general population, and probably reflects a local hyperplastic response of hepatocytes to a vascular abnormality. Most lesions are diagnosed incidentally and the natural history of the disease remains largely unknown. Studies have reported that most FNH patients remain stable, or even regress, over a long follow-up period.12345

It is difficult to select the surgical indication for patients with benign disease, such as FNH. FNH itself is a benign disease, thus it does not require surgical resection unless symptoms persist. However, currently available diagnostic modalities do not reliably confirm the diagnosis of FNH, and exclude other diseases requiring surgical treatment.8 Thus, surgery is occasionally considered.

The most common reason leading to surgical treatment in our study was uncertainty of diagnosis through imaging studies. Even when percutaneous biopsy diagnosed FNH, if the imaging study findings were still suspicious of hepatic adenoma, HCC, or other malignant diseases, surgery had to be performed.

In a single-center study with 100 cases of FNH, the indications for liver resection included tumor-associated symptoms with abdominal discomfort (40.7%), balance of risk for malignancy/history of cancer (47.8%/33.3%), tumor enlargement/jaundice of vascular and biliary structures (11.5%), and incidental findings during elective surgery (0.9%). The authors suggested that hepatic resection was a valuable therapeutic option in the treatment of either symptomatic FNH or when malignancy could not be ruled out. If clinically indicated, liver resection for FNH represents a safe approach and may lead to significant improvement in of quality of life, especially in symptomatic patients.9

Continuously-growing tumor was also one of the common reasons leading to surgery, because such a finding can be associated with malignancy. However, a study reported that FNH may grow significantly without causing symptoms and a significant increase in size did not affect clinical management if a confident diagnosis by imaging had been established.10 FNH has been reported to have the potential for spontaneous regression, thus giant FNH can be managed conservatively, rather than by resection.11

The typical imaging findings of FNH include isoattenuation in pre-contrast CT; T1, T2 isointensity with T2 hyperintense central scar on MRI; homogenous arterial enhancement on CT or MRI post-contrast; and delayed enhancement of central scar. Dynamic CT and dual contrast MRI are important tools for diagnosing FNH. However, it is very difficult to diagnose FNH without central stellate scar findings. A Korean study suggested that contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) using Sonazoid for FNH showed typical vascular patterns of central artery vascularity, stellate vascularity, and centrifugal enhancement. Most cases were either hyperenhanced or isoenhanced on serial dynamic- and Kupfferphase imaging. Based on these results, CEUS can provide useful information for noninvasive FNH diagnoses.12 A Japanese study reported points useful in the imaging differentiation of HCC showing hyperintensity on the hepatobiliary phase of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI, from FNH and FNH-like nodules. The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) was lower in hyperintense HCC than in FNH. The enhancement patterns of hyperintense HCC and FNH at dynamic CT were significantly different. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the ADC ratio (p=0.03; odds ratio=0.12) and the enhancement pattern at dynamic CT (p=0.04; odds ratio=16.21) were independent factors for differentiation between hyperintense HCC and FNH. The authors suggested that arterial phase enhancement and washout pattern at dynamic CT, and decreases in the ADC ratio, were important findings for diagnosis of hyperintense HCC differentiated from FNH and FNH-like nodules.13

The patterns of liver tumor development can be very complex, thus, FNH can occur concurrently with other disease entities. In this study, two patients had concurrent pathologies of hepatic adenoma and angiosarcoma in preoperative percutaneous biopsy findings, which were confirmed by post-resection pathology. In fact, pre- and malignant lesions became the primary reasons for surgical treatment. The possibility of other concurrent lesions could not be excluded, especially in patients with multiple lesions.14

There were limitations in this study. First, this was a retrospective study. Patients diagnosed with FNH after surgery were selected. Therefore, patients without suspected FNH before surgery, but diagnosed with other diseases after surgery, were not included. Second, it was a small-volume single-center study. Therefore, it was difficult to draw reliable conclusions. Third, administration of oral contraceptives is not common in Korean society, so its association with development of FNH could not be assessed.

In conclusion, FNH can be diagnosed by imaging studies, but surgical treatment can be considered in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or persistent symptoms.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Preoperative imaging and operative findings of a 58 year-old male patient showing focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) with an angiosarcoma component. Computed tomography (A: arterial phase and B: portal phase) and magnetic resonance imaging (C) suggested FNH or adenoma. Percutaneous biopsy suggested angiosarcoma. The pathological examination of the resected specimen (D) revealed a final diagnosis of FNH, with multifocal well-differentiated adenosarcoma.

Fig. 2

Preoperative imaging and operative findings of a 31 yearold male patient showing large focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). Computed tomography (A: arterial phase and B: portal phase) and magnetic resonance imaging (C) suggested FNH. The pathological examination of the resected specimen (D) revealed a final diagnosis of FNH.

References

1. Stocker JT, Ishak KG. Focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: a study of 21 pediatric cases. Cancer. 1981; 48:336–345.

2. Di Stasi M, Caturelli E, De Sio I, Salmi A, Buscarini E, Buscarini L. Natural history of focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: an ultrasound study. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996; 24:345–350.

3. Mathieu D, Kobeiter H, Maison P, Rahmouni A, Cherqui D, Zafrani ES, et al. Oral contraceptive use and focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Gastroenterology. 2000; 118:560–564.

4. Leconte I, Van Beers BE, Lacrosse M, Sempoux C, Jamart J, Materne R, et al. Focal nodular hyperplasia: natural course observed with CT and MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000; 24:61–66.

5. Kuo YH, Wang JH, Lu SN, Hung CH, Wei YC, Hu TH, et al. Natural course of hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia: a long-term follow-up study with sonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009; 37:132–137.

6. Song KH, Lee KU, Kim JH, Shin WY, Lee HW, Yi NJ, et al. Clinical analysis of focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver in 11 patients. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007; 11:41–46.

7. Cho HD, Hwang S, Lee YJ, Park KM, Kim KH, Kim JC, et al. Changes in the types of liver diseases requiring hepatic resection: a single-institution experience of 9016 cases over a 10-year period. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2016; 20:49–52.

8. Jung DH, Hwang S, Hong SM, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, et al. Clinico-pathological correlation of hepatic angiomyolipoma: a series of 23 resection cases. ANZ J Surg. 2018; 88:E60–E65.

9. Hau HM, Atanasov G, Tautenhahn HM, Ascherl R, Wiltberger G, Schoenberg MB, et al. The value of liver resection for focal nodular hyperplasia: resection yes or no? Eur J Med Res. 2015; 20:86.

10. Bröker MEE, Klompenhouwer AJ, Gaspersz MP, Alleleyn AME, Dwarkasing RS, Pieters IC, et al. Growth of focal nodular hyperplasia is not a reason for surgical intervention, but patients should be referred to a tertiary referral centre. World J Surg. 2018; 42:1506–1513.

11. Mamone G, Caruso S, Cortis K, Miraglia R. Complete spontaneous regression of giant focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: magnetic resonance imaging evaluation with hepatobiliary contrast media. World J Gastroenterol. 2016; 22:10461–10464.

12. Lee J, Jeong WK, Lim HK, Kim AY. Focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: contrast-enhanced ultrasonographic features with sonazoid. J Ultrasound Med. 2018; 37:1473–1480.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download