Abstract

Methods

In this descriptive cross-sectional study, 200 midwives were selected through convenience sampling method from private and public clinics in Mashhad, North East of Iran. A self-structured questionnaire was used to collect the study data.

Results

The mean age of subjects was 39.58 ± 8.12 years with 13.49 ± 7.59 years of work experience. A number of cultural conditions act as an inhibitory force for the midwives to address sexual issues with menopausal women. Menopausal women visit a doctor at the acute stage when emotional and physical problems make sexual discussion difficult for the midwives (86.5%). Other related causes for not having proper sexual conversation were insufficient knowledge (51.4%), inadequate education provided via public media through health providers (83.5%), midwives or their patient's shame (51.5%), and attempt to get help from traditional healers, friends, relatives and supplicants instead of midwifery staff (78.5%). Also, we found that sexual workshops, communication workshops, and work experiences had a significant influence in changing the views of midwives.

One of the important parts of the holistic care is sexual health care. Sexual health is considered as essential part of holistic care, while sexual problems are not being commonly discussed by the most of the health care providers and their patients.1234 This could be due to several reasons, including personal and demographic characteristics of the health providers such as their age, gender, level of education, work experience, birthplace, and the country they have graduated in, as well as their patients' embarrassment and the level of self-confidence of health care providers.356789

Some health care providers may believe that giving the emergency problems of the patients, sexuality cannot be the first priority, and having a sexual conversation can elevate the patient's anxiety,8 which can be affected by their religious beliefs and negative attitudes toward sexuality.10

Some environmental barriers could be associated with addressing sexuality, including insufficient support of nursing management, having concerns about possible negative reactions of other healthcare providers, lack of a proper role model for having sexual conversation, presence of the patient's spouse (38%) and relatives (65%) and insufficient education in this regard.78

Giving the importance of cultural beliefs in Iran, we believe that cultural issues are important enough to be considered as a separate section. Therefore, this study conducted to identify cultural barriers influencing midwives' point of view in this regard. Understanding such barriers could help to provide valuable information, which is needed for the future programs to promote sexual health care for menopausal women in Iran. The present study aimed to determine the barriers influencing sexual conversation.

It is worthy to note that this is part of a larger study that focused on leading factors to predict midwives' sexual discussion. The initial protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Science, Mashhad, Iran. A total of 200 midwives were selected through convenience sampling method from private and public clinics affiliated to Mashhad University of Medical Science in 2016. Inclusion criteria were willingness to participate in the study and history of at least 2 years of work experiences in clinical settings. The exclusion criteria included not responding to 10% of questions in the questionnaire. All of the subjects signed a consent form. Data were collected on the basis of a self-structured questionnaire developed based on deeply qualitative interview and a wide review of literature.

The content validity of the questionnaire was determined by an expert panel consisting of faculty members in reproductive health and midwifery (n = 8), nursing (n = 2) and psychometry (n = 4) departments at Mashhad and Isfahan Universities of medical sciences. Two types of content validity were measured: content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR). The CVI for all items was 100% and the CVR was satisfactory ranging from 0.71% to 100%.

Descriptive statistics was conducted using SPSS statistical software (version 11.01; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine item-to-item correlation and item-total correlation. The relation between midwives general characteristic and questionnaires items were assessed using analysis of variances (ANOVA) and 2 sample t-test.

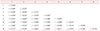

The mean age of subjects was 39.58 ± 8.12 years with 13.49 ± 7.59 years of work experience. In terms of marriage status, 38 (19.0%) were single, 158 (79%) were married and 4 (2%) were widow. The characteristics of studied midwives are shown in Table 1. Table 2 showed item-to-item correlation and item-total correlation.

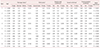

As midwifes become older, their own or their patient's shame could have less influence on the midwives' hesitance to address the respective issues for their patients (P = 0.02; r = −0.164). The number of years of work experience showed a negative correlation with item 5 “To what extent does your own shame or postmenopausal woman's shame make it easy / difficult for you to have sexual conversation”. The findings implied, as midwives become more experienced, their own or their patient's shame could have less influence on the midwives' hesitance to address the respective issues for their patients (r = −0.146; P = 0.04) (Table 3).

Almost half of the midwives (51.4%) believed that menopausal women's insufficient knowledge makes it difficult for them to have sexual conversation with menopausal women. The subjects believed that menopausal women called health care provider only when they reach the acute stages of physical problems such as pelvic organ prolapse, severe vaginal dryness or emotional stresses such as marital infidelity. This barrier makes sexual discussion difficult for 86.5% of midwifes. In their opinion, public media does not provide sufficient education to prepare menopausal women to have conversation with health care providers. This barrier makes sexual discussion difficult for 83.5% of the midwifes (Table 4).

Midwives believed that negative attitudes and stereotypes about sexual issues (e.g., considering sexual relations as an obscenity in old ages, believing in masculine sexuality, poor body image, and some sexual problems caused by aging) prevent the patients to have sexual conversation with them. This barrier makes sexual discussion difficult for 85.5% of midwifes. Almost half of the subjects (51.5%) reported that their own shame or their patient's shame makes it difficult for them to have sexual conversation. Two-thirds of subjects believed that medicalization of sexual problems by patients make sexual conversation difficult for them. Midwives believed that their patients are not willing to address their sexual problems to the midwife because such issues are less important for them. This barrier makes sexual discussion difficult for 81% of midwifes. The subjects believed that postmenopausal women in dealing with sexual problems get help from traditional therapists, friends, relatives and supplicants instead of midwifery staff. This barrier makes sexual discussion difficult for 78.5% of midwifes (Table 4).

The findings also showed that the midwives who attended in workshops on sexual issues were less likely affected by their shame or patients' shame. Midwives worked in private offices were less likely affected by barriers related to items 5, and 6 “To what extent does the medicalization of sexual problems by patients make it easy / difficult for you to have sexual conversation?” (Table 3).

Menopause is one of the normal stages that experience by all women in their life. It can impact on menopausal women's quality of life. Therefore it is important to assess women's problem in this stage.1112 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to assess solely cultural barriers to address the sexual issues among menopausal women in Iran. A number of various cultural conditions inhibited midwives to address sexual issues with menopausal women. We found that sexual workshops, communication workshops and work experiences significantly influence midwives sexual discussion with their patients.

When comparing the studies conducted on all age groups in the other cities of Iran, more number of midwives stated that cultural issues inhibited them from discussing sexual problems with their patients.313 This discrepancy may be explained partially with more sensitive sexual issues in older people and taboo surrounded sexuality issues in older people. Almost half of the subjects in current study mentioned that their own shame or their patient's shame make sexual conversation difficult for them. Many studies have presented embarrassment of patients or health care provider as barriers to address sexuality issues of patients.47141516 Most of the primary care provider (90%) participated in a study of Kushner and Solorio7 in 2007 reported seldom or never feeling of embarrassment. But, they believed that 58% of their female patients are embarrassed when they take a sexual history. In Hordern et al.'s study15 in 2009, the mean score for question “I might become embarrassed” on a 5-point Likert scale was 3.115. In another study general practitioners (GPs) mentioned that the embarrassment of their own (8.3%) or patients (73.1%) can be as a barrier for interaction between doctor and patient.16 Guthrie14 in 1999 in a qualitative study reported that many nurses noted high levels of embarrassment performing intimate, some invasive procedure like giving young guys suppositories. Humphery and Nazareth16 in 2001 in their survey found that only 15% of GPs considered lack of knowledge and awareness of their patients as a barrier for addressing the sexual issues. In the current study, most of the subjects (76%) did not talk about sexual issues with the patients.

Rashidian et al.3 in 2013 found that the physicians graduated from America are more proactive and sensitive to discuss the sexuality with the patients. Also their study showed that Iranian-American Physicians' attitude towards taking a sexual history may be influenced by their place of graduation and place of births, possibly influenced by culture. Our study showed that presumptions or stereotypical views play a role to provide sexual care for menopausal women, which is inconsistent with the reports by Steinke et al.17 and Rashidian et al.3. According to the current study findings, the stereotypical views of midwives like thinking about less importance of sexuality to women prevent them from discussing sexual issues, which is in accordance with the results of Rashidian et al.3.

Our study had several strengths. First, a reliable and validated questionnaire based on earlier qualitative study was used. Second, response rate was very higher than previous studies. It may be due to the fact that previous studies distributed questionnaire using e-mail. Last, the study was performed in Mashhad, which is a multicultural city. Then, these findings may be generalized to the entire of Iran country. Also, our study had several limitations that it is worthy to address when interpreting findings. First, this study was performed in Iran that may limit generalizability of the findings to only Iranian population. Second, the percentage of shame for either patients or midwives were not separable on the current questionnaire. Therefore, we think that the question “To what extent does your own shame or postmenopausal woman's shame make it easy / difficult for you to have sexual conversation?” should be separated “to what extent does your own shame make difficult/easy sexual discussion with menopausal women” and “to what extent does menopausal woman's shame makes sexual discussion difficult?” Fourth, the convenience sampling method was used to include participants in study instead of random sample. Last, the sexuality is considered as taboo in Iranian culture, which may affect our data.

Insufficient knowledge of the patients regarding sexuality, patients' refusal to visit a physician until reaching the acute stages, medicalization of sexual problems, presumption of less importance of sexuality for menopausal women, strongly, inhibited midwives to address the sexual issues. The findings of this study can be utilized to provide suitable guidelines with regard to certain sensitivities of the Iranian culture.

Figures and Tables

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (Grant No. 930568).

References

1. Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Segal JL, Silva WA, Goldenhar LM, Karram MM. Practice patterns of physician members of the American Urogynecologic Society regarding female sexual dysfunction: results of a national survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005; 16:460–467.

2. Dyer K, das Nair R. Why don't healthcare professionals talk about sex? A systematic review of recent qualitative studies conducted in the United kingdom. J Sex Med. 2013; 10:2658–2670.

3. Rashidian M, Minichiello V, Knutsen SF, Ghamsary M. Barriers to sexual health care: a survey of Iranian-American physicians in California, USA. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016; 16:263.

4. Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, Selby P. Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. Br J Cancer. 2003; 88:666–671.

5. Salehian R, Naserbakht M, Mazaheri A, Karvandi M. Perceived barriers to addressing sexual issues among cardiovascular patients. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2017; 11:e7223.

6. Ghazanfarpour M, Khadivzadeh T, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Mehdi Hazavehei SM. Obstacles to the discussion of sexual problems in menopausal women: a qualitative study of healthcare providers. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017; 37:660–666.

7. Kushner M, Solorio MR. The STI and HIV testing practices of primary care providers. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007; 99:258–263.

8. Magnan MA, Reynolds K. Barriers to addressing patient sexuality concerns across five areas of specialization. Clin Nurse Spec. 2006; 20:285–292.

9. Ghazanfarpour M, Khadivzadeh T, Roudsari RL. Sexual disharmony in menopausal women and their husband: A qualitative study of reasons, strategies, and ramifications. J Menopausal Med. 2018; 24:41–49.

10. Kottmel A, Ruether-Wolf KV, Bitzer J. Do gynecologists talk about sexual dysfunction with their patients? J Sex Med. 2014; 11:2048–2054.

11. Yoshany N, Morowatisharifabad MA, Mihanpour H, Bahri N, Jadgal KM. The effect of husbands' education regarding menopausal health on marital satisfaction of their wives. J Menopausal Med. 2017; 23:15–24.

12. Heidari M, Ghodusi M, Rafiei H. Sexual self-concept and its relationship to depression, stress and anxiety in postmenopausal women. J Menopausal Med. 2017; 23:42–48.

13. Ozgoli G, Sheikhan Z, Dolatian M, Valaee N. The survey of obstacle and essentiality health providers for sexual health evaluation in women referring to health centers related of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Pejouhandeh. 2014; 19:175–183.

14. Guthrie C. Nurses' perceptions of sexuality relating to patient care. J Clin Nurs. 1999; 8:313–321.

15. Hordern A, Grainger M, Hegarty S, Jefford M, White V, Sutherland G. Discussing sexuality in the clinical setting: The impact of a brief training program for oncology health professionals to enhance communication about sexuality. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2009; 5:270–277.

16. Humphery S, Nazareth I. GPs' views on their management of sexual dysfunction. Fam Pract. 2001; 18:516–518.

17. Steinke EE, Jaarsma T, Barnason SA, Byrne M, Doherty S, Dougherty CM, et al. Sexual counselling for individuals with cardiovascular disease and their partners: a consensus document from the American Heart Association and the ESC Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (CCNAP). Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:3217–3235.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download