INTRODUCTION

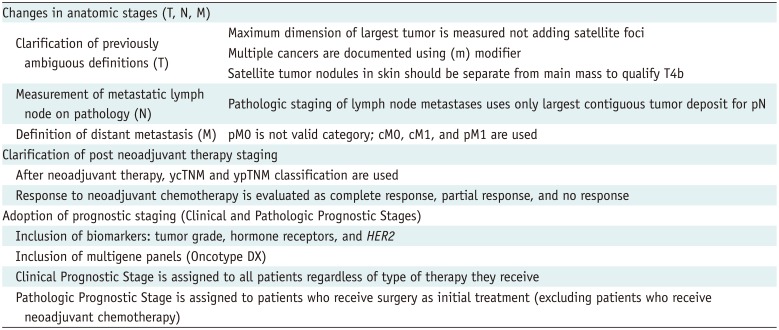

Table 1

Summary of Changes in 8th Edition

Brief Overview of the 7th Edition

Table 2

7th Edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for Breast Cancer

Changes in the Anatomic Stage

Tumor

| Fig. 1Measurement of tumor size.Maximum tumor size measures 4.3 cm on ultrasound image (arrow). It also measures 4.3 cm pathologically. Therefore, both clinical and pathologic T category is T2. T = tumor

|

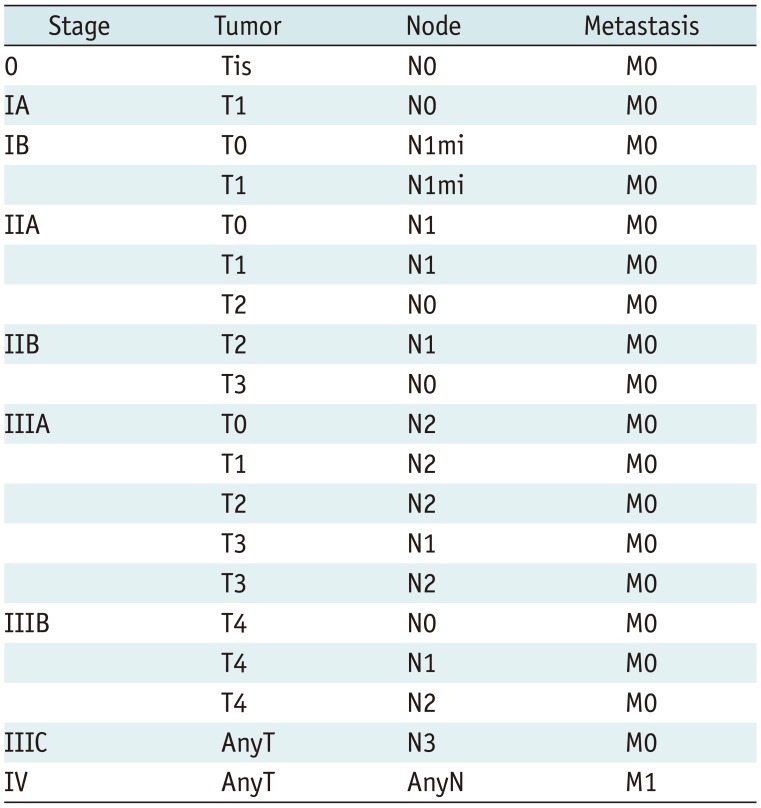

| Fig. 2Determination of T categories.

A. Maximum size of largest tumor is measured (solid line), but size of smaller tumors is not added (dotted line). B. Magnetic resonance maximum intensity projection image demonstrates multiple synchronous tumors in breast. Maximum invasive size of largest tumor is 2.4 cm (arrow), and size of smaller tumors (arrowheads) is not added. Therefore, cT2 (m) is designated for T stage.

|

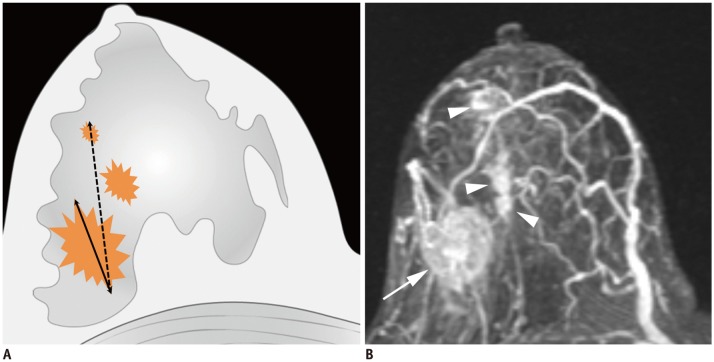

| Fig. 3T4b breast cancer.MRI shows primary breast cancer in left upper breast (arrowheads). Separate skin nodule is identified at left upper outer part, which qualifies as T4b (arrow). MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

|

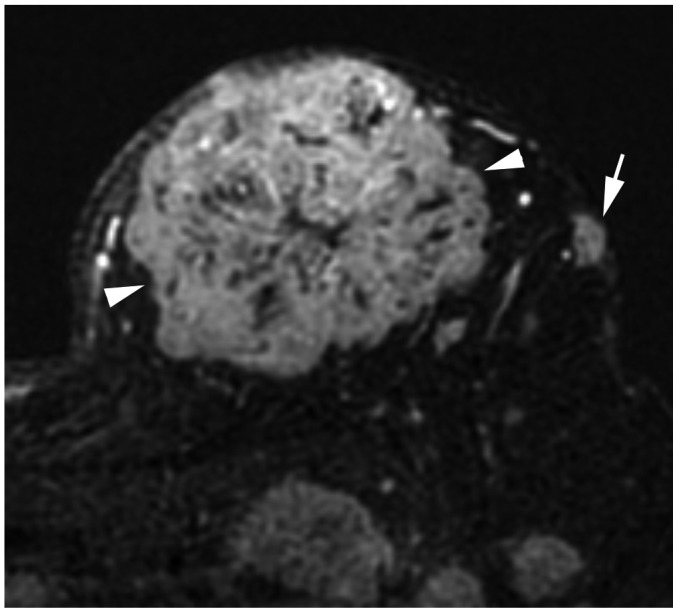

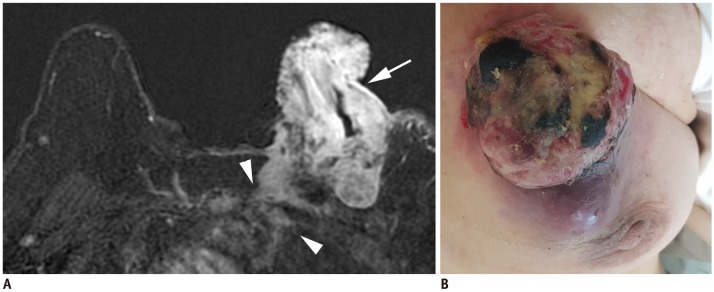

| Fig. 4T4c breast cancer.

A. MRI shows left breast cancer with skin ulceration (arrow) and rib extension (arrowheads). B. Physical examination shows ulceration extending to less than one third of breast, which does not meet definition of IBC. IBC = inflammatory breast cancer

|

| Fig. 5Left IBC (T4d).

A. MRI shows diffuse skin enhancement (arrowheads) and chest wall extension (arrow). B. Physical examination of left breast shows erythema and peau d'orange (orange peel skin) appearance of skin, which meets definition of IBC.

|

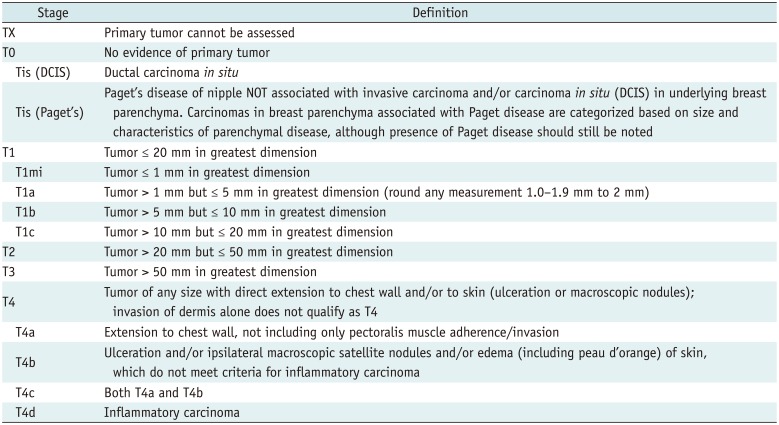

Table 3

Definition of Primary T Categories

Lymph Nodes

| Fig. 6cN3 category.

A, B. cN3a: Ultrasound images from right breast cancer case show enlarged hypoechoic lymph nodes with loss of fatty hilum not only in right axilla (A) level II (arrows), but also on (B) level III (arrow). Note pectoralis minor muscle (arrowheads), which is landmark for grouping axillary lymph nodes. C, D. cN3b: (C) MRI of case of cancer in right breast shows enlarged lymph nodes in right axilla (arrow). (D) Enlarged right internal mammary lymph node is also noted (arrowhead). E, F. cN3c: (E) Ultrasound of left breast cancer case shows enlarged lymph node in left axilla (arrow). (F) Enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node is also noted (arrowhead). AX = axilla

|

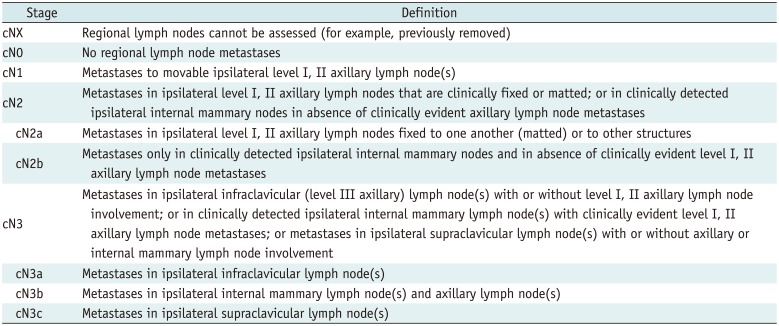

Table 4

Definition of Clinical Regional Lymph N Categories

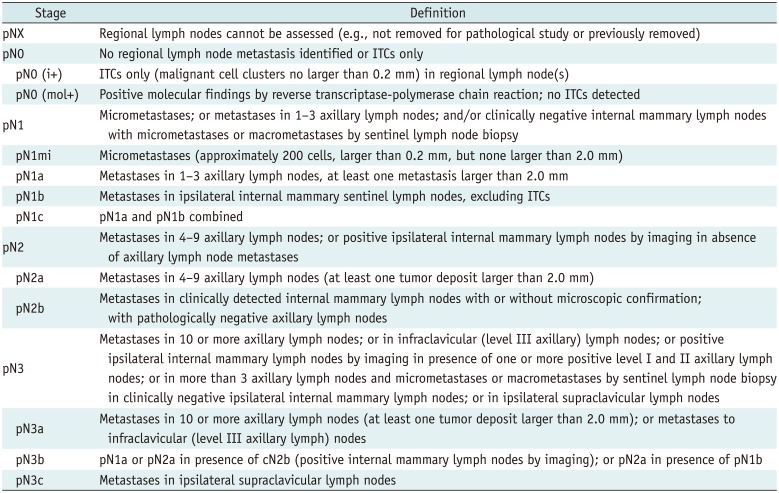

Table 5

Definition of Pathologic Regional Lymph N Categories

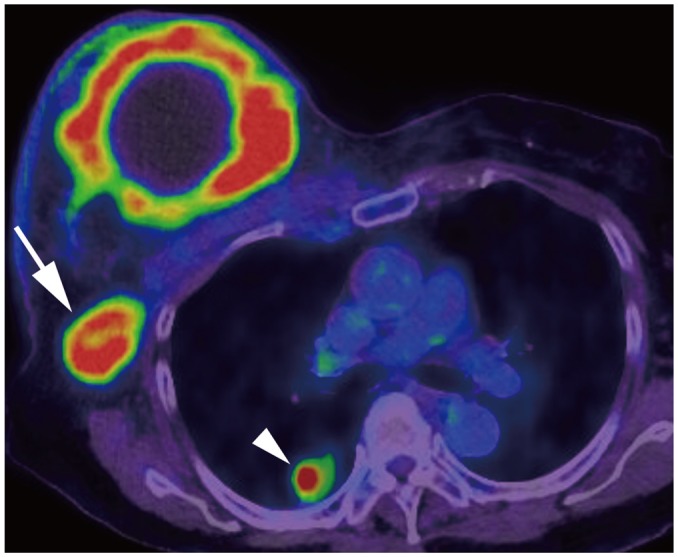

Metastasis

| Fig. 7Right breast cancer with lung metastasis (M1).On positron emission tomography-computed tomography, 10-cm cancerous mass is seen in right breast and multiple FDG uptakes are seen in right axillary lymph nodes (arrow); there are lung nodules with FDG uptake, suggesting lung metastasis (arrowhead). FDG = fludeoxyglucose, M = metastasis

|

Table 6

Definition of Distant M Categories

Post-Neoadjuvant Therapy Staging

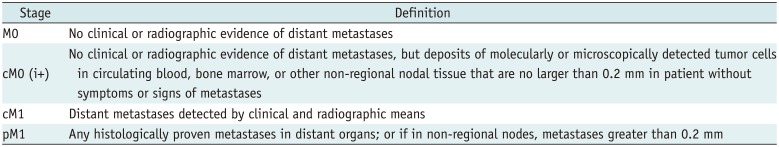

| Fig. 8Size measurement after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

A. Initial MRI shows 4.3-cm irregular breast cancer in left breast (T2) (arrow). B. After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, cancer reduced to multiple small masses (arrowheads); largest one measures 10 mm (arrow). Therefore, post treatment T category is ycT1b (m).

|

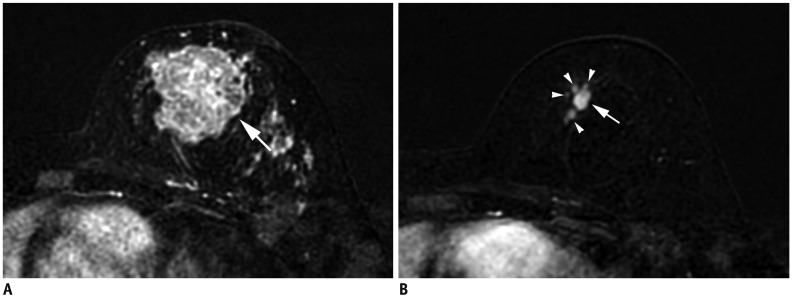

| Fig. 9Patient with cancer in right breast with MRI before (A, B) and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (C, D).

A. Initial MRI shows 2.2-cm right breast cancer (arrow). B. Ipsilateral matted axillary lymph node enlargement is noted (arrows). Initial stage is T2N2aM0. C. After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there is no residual mass. D. Axillary lymph nodes have disappeared, which suggests clinical CR (ycT0N0M0). Histopathologic evaluation shows absence of invasive carcinoma in breast and lymph nodes, indicating pathologic CR (ypT0N0M0). CR = complete response

|

Adoption of the Prognostic Stage

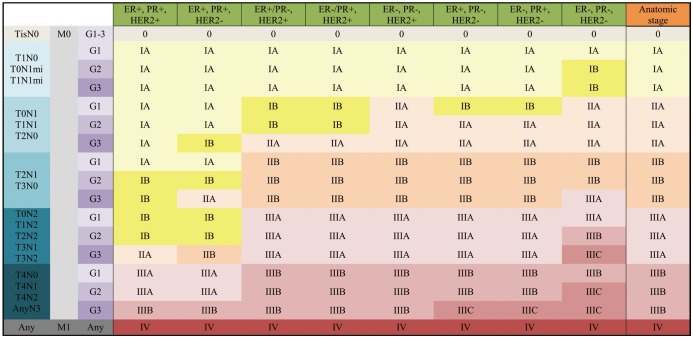

| Fig. 10Clinical Prognostic Stage is assigned to all patients regardless of type of therapy given.ER− = estrogen receptor-negative, ER+ = ER-positive, G = grade, HER2− = HER2 negative, HER2+ = HER2-positive, mi = micrometastasis, PR− = progesterone receptor-negative, PR+ = PR-positive, Tis = in situ

|

Tumor Grade

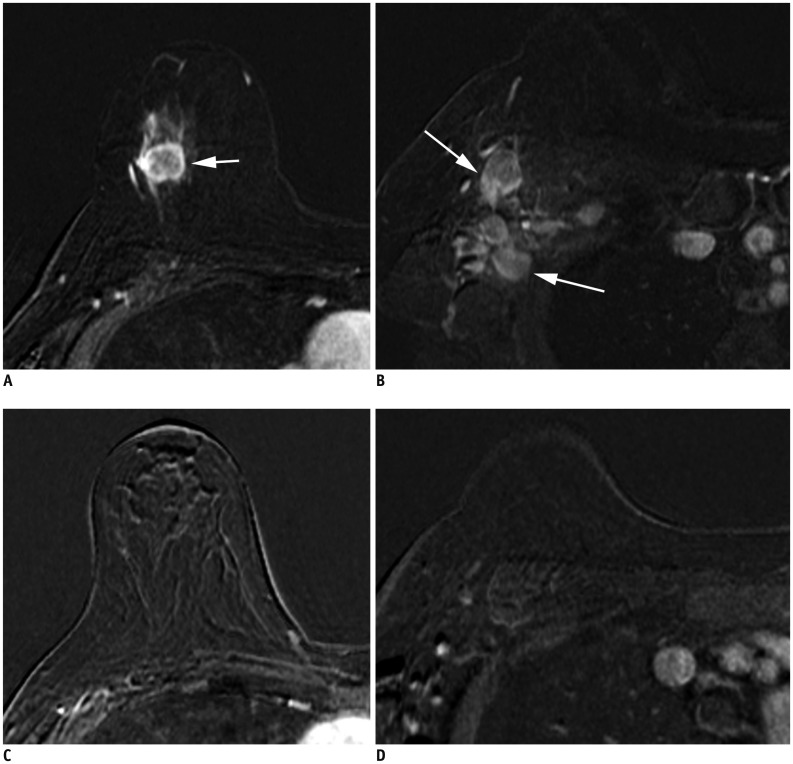

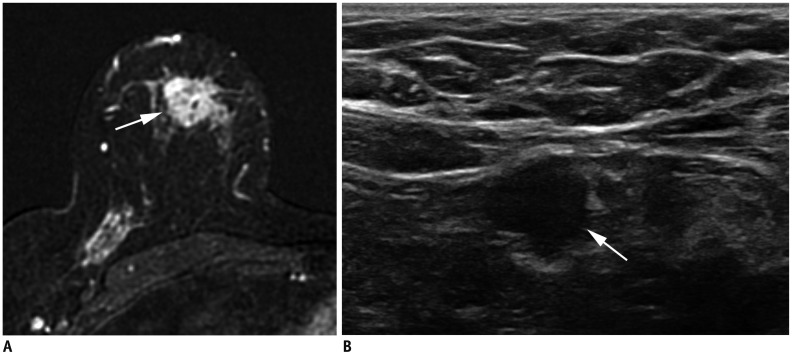

| Fig. 12Right breast cancer with low histologic grade.

A. MRI demonstrates breast cancer measuring 2.3 cm in upper breast (arrow). B. Ultrasound shows enlarged, right axillary lymph node with eccentric cortical thickening (arrow). After partial mastectomy, cancer measures 2.5 cm with two level-I lymph node metastases. Cancer is ER+/PR+ and HER2−. Histologic grade is 1, and anatomic stage is IIB (T2N1M0). However, due to low histologic grade and biomarker status, Clinical Prognostic Stage is IIA and Pathologic Prognostic Stage is IA.

|

Hormone Receptor and HER2 Expression

| Fig. 13cT1N0M0 cancer.MRI shows that cancer measures 1.3 cm (arrow). There is no suspicious lymph node enlargement. Pathology shows 0.9-cm grade-2 carcinoma, but no hormone receptor or HER2 overexpression is noted. Therefore, anatomic stage is IA (T1N0M0), but it is triple negative cancer; thus, Clinical and Pathologic Prognostic Stages are higher, IB.

|

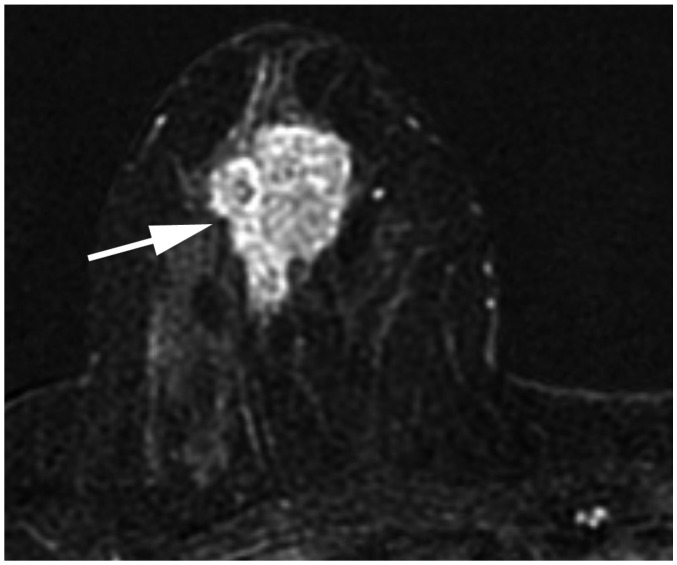

Multigene Panel Status

Prognostic Stage Groups

| Fig. 14cT2N0M0 cancer.MRI shows 3.7-cm enhancing cancer (arrow). No axillary metastasis is found. Anatomic stage is IIA. Tumor grade is 3, and hormone receptor and HER2 expressions are negative. This tumor has high histologic grade and is triple-negative; therefore, Clinical Prognostic Stage is higher, IIB.

|

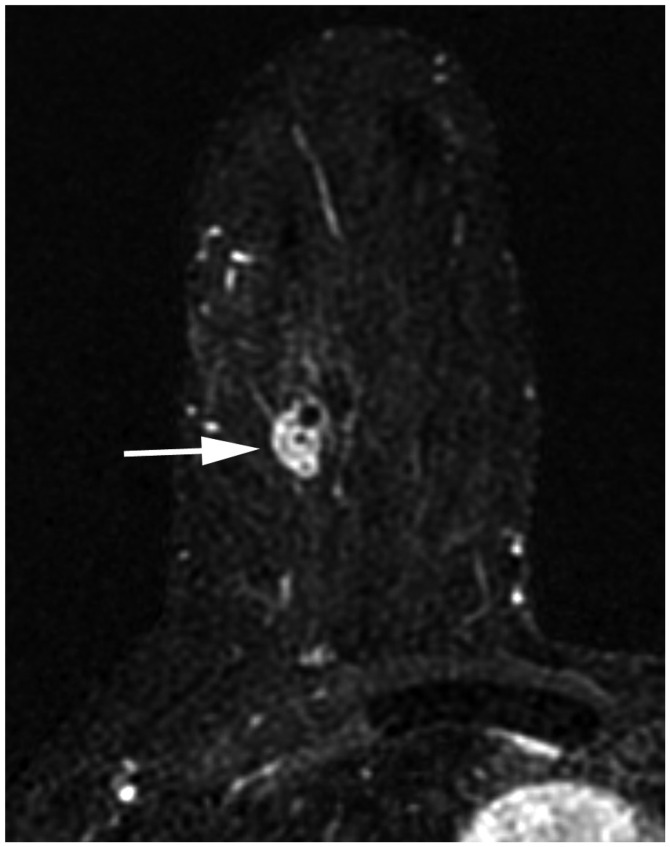

| Fig. 15cT3N1M0 cancer downgraded by prognostic stage.

A. Ultrasound image indicates complex cystic and solid mass in left lower outer breast (arrows). B. Left axillary ultrasound image shows cortically thickened lymph node (arrow). Anatomic stage is IIIA. Tumor grade is 1, ER and PR expression are found, and HER2 shows no overexpression; therefore, Clinical Prognostic Stage is IIA, and Pathologic Prognostic Stage is IB.

|

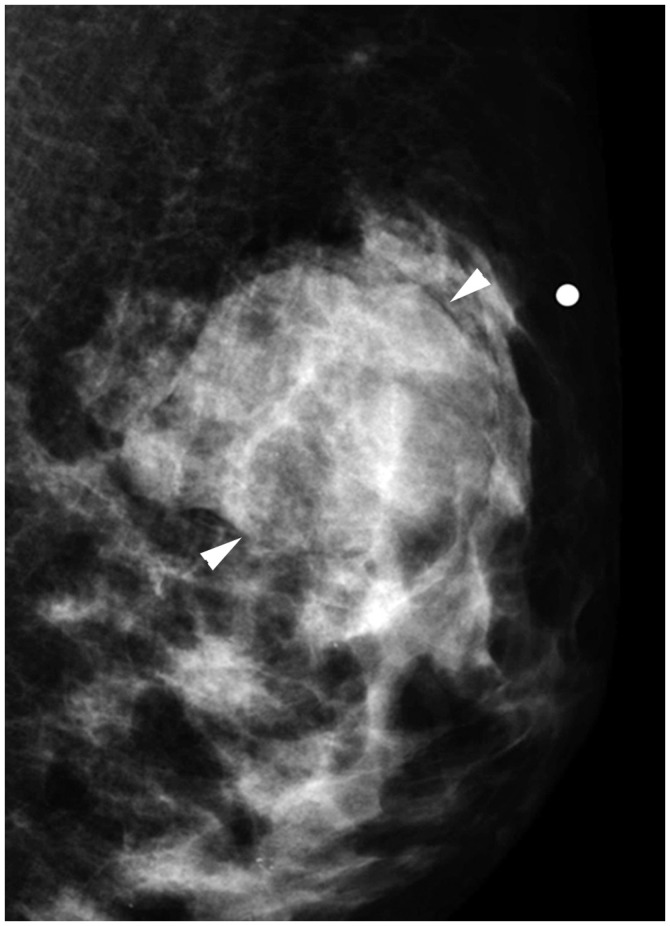

| Fig. 16cT2N0M0 cancer.Mediolateral oblique mammographic view demonstrates mass in left upper outer breast (arrowheads). Lymph nodes are not enlarged. Anatomic stage is IIA. Tumor is ER expression positive, HER2 shows no overexpression, and Oncotype Dx recurrence score is 5; therefore, Pathologic Prognostic Stage is IA.

|

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download