Abstract

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is widely used to provide nutritional support for patients with dysphagia and/or disturbed consciousness preventing oral ingestion, and PEG tube placement is a relatively safe and convenient non-surgical procedure performed under local anesthesia. However, the prevention of PEG-insertion-related complications is important. A 64-year-old man with recurrent pneumonia underwent tracheostomy and nasogastric tube placement for nutritional support and opted for PEG tube insertion for long-term nutrition. However, during the insertion procedure, needle puncture had to be attempted twice before successful PEG tube placement was achieved, and a day after the procedure his hemoglobin had fallen and he developed hypotension. Abdominal computed tomography revealed injury to a pancreatic branch of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) associated with bleeding, hemoperitoneum, and pancreatitis. Transarterial embolization was performed using a microcatheter to treat hemorrhage from the injured branch of the SMA, and the acute pancreatitis was treated using antibiotics and supportive care. The patient was discharged after an uneventful recovery. Clinicians should be mindful of possible pancreatic injury and bleeding after PEG tube insertion. Possible complications, such as visceral injuries or bleeding, should be considered in patients requiring multiple puncture attempts during a PEG procedure.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a procedure that is widely performed to provide nutritional support in patients with dysphagia and/or disturbed consciousness. PEG was first introduced in the 1980s by Gauderer et al.,1 and has been used in patients with dysphagia secondary to stroke or brain damage and in patients in whom oral ingestion is not possible owing to facial damage, or rhinopharyngeal or esophageal malignancies.23 PEG tube placement is a relatively safe and convenient non-surgical procedure performed under local anesthesia,4 but it is important that patients be monitored closely to prevent complications resulting from PEG tube insertion-related procedures. We report a rare case of injury to a pancreatic branch of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) associated with bleeding after PEG tube insertion and provide a review of pertinent literature.

A 66-year-old man was diagnosed with herpes encephalopathy in 1994 and reported a history of receiving medication from a Neurology Department. He had also received medication for diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism. In addition, the patient reported a history of recurrent pneumonia and that he had undergone tracheostomy and nasogastric tube placement for nutritional support. At this presentation, he reported dysphagia and frequent episodes of aspiration pneumonia, and opted for PEG tube insertion for long-term nutrition.

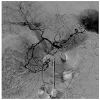

His vital signs were stable upon admission. Initial laboratory data showed: white blood cells 6,830/mm3, hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL, platelets 92,000/mm3, AST 18 U/L, ALT 6 U/L, BUN 15 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.61 mg/dL. The low platelet count appeared to be due to the valproate medication the patient was taking. Prior to the PEG tube insertion procedure, he had remained in a fasting state for >8 hours admission and received prophylactic antibiotics. Needle puncture was attempted twice during the PEG placement procedure, but the remainder of the procedure was completed normally (Fig. 1) without any immediate post-procedural complication. However, a day after the procedure, the patient developed hypotension, tachycardia, and dyspnea and exhibited a slight increase in abdominal circumference. In addition, his hemoglobin had dropped from 12.1 to 9.4 g/dL. Nasogastric tube washings and a rectal examination did not reveal any specific findings. However, abdominal CT showed leakage of contrast medium from a pancreatic branch of the SMA and moderately sized fluid collection of high attenuation in the perihepatic and perisplenic spaces, and in the pelvic cavity, suggesting the presence of hemoperitoneum, and the presence of acute pancreatitis (Fig. 2). Pancreatic enzyme levels were very high, in particular, amylase and lipase levels were 1,516 U/L and >8,000 U/L, respectively. The pancreatitis was presumed to have been caused by injury during PEG tube insertion. Transarterial embolization was performed to treat the hemorrhage from the injured pancreatic branch of the SMA. Angiography had revealed no active bleeding, and thus, the bleeding artery had not been clearly identified. Gelfoam microembolization was performed based on considerations of abdominal CT findings (Fig. 3). After embolization, vital signs stabilized without any further suspicion of bleeding.

PEG tube insertion is widely used to provide enteral nutrition in patients with dysphagia or in those that have undergone pharyngeal or esophageal surgery and in whom oral ingestion is difficult/impossible.23 PEG can be performed under local anesthesia, and thus, is less invasive and more cost-effective than surgery.45

PEG is performed in patients diagnosed with cerebrovascular disease, dementia, or motor neurological disease, in patients with dysphagia and/or disturbed consciousness secondary to brain damage, and in patients with head and neck or esophageal cancer. It can also be used to provide enteral nutrition to patients with oral ingestion difficulties.67

PEG is usually a safe procedure, but complications occasionally occur, and although wound infection is the most common complication, granuloma formation, tube dislodgement, peritonitis, visceral injuries, intestinal obstruction, aspiration pneumonia, bleeding, fistula formation, buried bumper syndrome, and necrotizing fasciitis have all been reported.89101112 Abdominal visceral or vascular injuries are rare but serious complications, which can be fatal.

Although any abdominal organ could be injured, the colon, small intestine, liver, and spleen are at greatest risk of injury during PEG tube insertion; traumatic intestinal perforation is more common in elderly patients. Symptoms of peritoneal irritation after PEG tube insertion can occur in patients with a suspected intestinal injury,1314 and abdominal CT is warranted in such patients. Treatment of intestinal injuries often requires laparotomy. A case reported at ACG Case Reports Journal described a patient that developed a splenic laceration and a short gastric vessel injury after PEG tube insertion, who recovered uneventfully after emergency splenectomy.15

Intraperitoneal hemorrhage during PEG tube placement is a relatively rare adverse effect that occurs in ~1% of patients.16 Furthermore, bleeding complications after PEG tube placement are relatively rare and have been usually reported as case reports. Table 1 lists details of vascular injuries that may occur during PEG tube insertion.

Amann et al.17 reported an incidence of massive bleeding secondary to arterial rupture of 0.9% (2/232) after PEG tube insertion. Bunai et al.18 described a case of left gastric artery bleeding after a PEG placement procedure unsuccessfully treated by angiographic embolization. Hong et al.19 reported a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the left gastric artery in a patient that developed hypotension and anemia 3 days after PEG tube placement and was treated successfully by embolization. Similarly, Lewis at al.20 reported the case of a 68-year-old woman who developed bleeding after PEG tube insertion and underwent successful embolization. In our patient, we performed embolization to treat bleeding from a pancreatic branch of the SMA, which had been injured during PEG tube insertion. The above-mentioned reports and our experiences demonstrate embolization can serve as a good treatment option for bleeding after PEG tube insertion.

Although rare, massive bleeding after PEG tube insertion is associated with mortality. One case report described an 83-year-old man who reportedly died from intra-abdominal hemorrhage secondary to pancreatic injury after PEG tube insertion. Autopsy findings revealed bleeding from a pancreatic branch of the splenic artery.11 Another case report described a 93-year-old woman who reportedly died from retroperitoneal bleeding after PEG tube insertion. In this case, autopsy findings revealed bleeding from the splenic and superior mesenteric veins. Both of these patients had undergone a cholecystectomy,12 and in both, autopsy findings revealed fibrosis and adhesions between liver and stomach. Because of postoperative changes that occur in intraperitoneal organs, these organs appear to be more vulnerable to hemorrhage resulting from needle puncture attempted twice during PEG tube insertion.

In our case, the 64-year-old man had not undergone any abdominal surgery, but the two puncture attempts performed during PEG are shared with the previous two case reports. In our patient, bleeding from the injured pancreatic branch of the SMA was treated by transarterial embolization and the acute pancreatitis by using antibiotics and supportive care, and the patient made a successful and uneventful recovery.

However, our case report differs from those previously reported as our patient showed bleeding from an injured pancreatic branch of the SMA, whereas previous reports describe patients that developed bleeding from an injured left gastric artery and splenic vein. In our case, the patient appeared to have been punctured from the front to the back of the stomach, resulting in damage to the pancreas situated posterior to the stomach.

PEG is usually safer than surgery in terms of hospital stays and costs, and thus, this endoscopic procedure is widely used by hospitals. We make the following suggestions to reduce vascular injury. First, the tip of the needle should be checked by endoscopy during the puncturing procedure. Second, the stomach must be properly inflated with air during tube insertion. Third, if possible, needle puncture should be achieved on first attempt. When two or more puncture attempts are required during the procedure, patients concerned should be closely monitored for hemorrhagic complications, and intra-abdominal hemorrhage should be suspected in those demonstrating hypotension and anemia without melena and/or gastrointestinal hemorrhage through the gastric tube after PEG tube insertion. Transarterial embolization may provide a good treatment option to manage post-procedural bleeding. We report a patient with a hemorrhagic injury to a pancreatic branch of the SMA and pancreatitis after PEG tube insertion and provide a review of the relevant literature.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2(A) Abdominal CT showed contrast media leakage from a pancreatic branch of the SMA suggestive of bleeding, and (B) moderate amounts of fluid collection with high attenuation in perihepatic and perisplenic spaces and pelvic cavity suggesting hemoperitoneum. CT, computed tomography; SMA, superior mesenteric artery. |

| Fig. 4Abdominal CT obtained one week after embolization showed no further bleeding but demonstrated the presence of acute pancreatitis and peripancreatic fluid collection. CT, computed tomography. |

References

1. Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg. 1980; 15:872–875.

2. Löser C, Müller MJ. Ethical guidelines for performing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG catheter). Z Gastroenterol. 1998; 36:475–478.

3. Rabeneck L, McCullough LB, Wray NP. Ethically justified, clinically comprehensive guidelines for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Lancet. 1997; 349:496–498.

4. Löser C, Wolters S, Fölsch UR. Enteral long-term nutrition via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in 210 patients: a four-year prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 1998; 43:2549–2557.

5. Grant JP. Comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with Stamm gastrostomy. Ann Surg. 1988; 207:598–603.

6. ASPEN Board of Directors and the Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002; 26:1 Suppl. 1SA–138SA.

7. Löser C, Aschl G, Hébuterne X, et al. ESPEN guidelines on artificial enteral nutrition--percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Clin Nutr. 2005; 24:848–861.

8. Lee HJ, Choung RS, Park MS, et al. Two cases of uncommon complication during percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube replacement and treatment. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2014; 63:120–124.

9. Schrag SP, Sharma R, Jaik NP, et al. Complications related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. A comprehensive clinical review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007; 16:407–418.

10. Naik RP, Joshipura VP, Patel NR, Haribhakti SP. Complications of PEG--prevention and management. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009; 30:186–194.

11. Smale E, Davison AM, Smith M, Pritchard C. Fatal intra-abdominal haemorrhage following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. BMJ Case Rep. 2009; 2009:bcr06.2009.2044.

12. Lau G, Lai SH. Fatal retroperitoneal haemorrhage: an unusual complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Forensic Sci Int. 2001; 116:69–75.

13. Lim YJ, Yang CH. Technique, management and complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 39:119–124.

14. Fang JC. Minimizing endoscopic complications in enteral access. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007; 17:179–196. ix

15. Patel BB, Andrade C, Doraiswamy V, Amodeo D. Splenic avulsion following PEG tube placement: a rare but serious complication. ACG Case Rep J. 2014; 2:21–23.

16. Rabeneck L, Wray NP, Petersen NJ. Long-term outcomes of patients receiving percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes. J Gen Intern Med. 1996; 11:287–293.

17. Amann W, Mischinger HJ, Berger A, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). 8 years of clinical experience in 232 patients. Surg Endosc. 1997; 11:741–744.

18. Bunai Y, Akaza K, Nagai A, Tsujinaka M, Jiang WX. Iatrogenic rupture of the left gastric artery during percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009; 11:Suppl 1. S538–S540.

19. Hong SH, Cha JM, Lee JI, et al. A case of ruptured left gastric artery pseudoaneurysm complicating Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG). Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 39:34–37.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download