This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Kawasaki disease (KD) sometimes presents with only fever and cervical lymphadenopathy before other clinical signs materialize. This lymphadenopathy-first-presenting Kawasaki disease (LKD) may be misdiagnosed as bacterial cervical lymphadenitis (BCL). We investigated characteristic imaging and clinical data for factors differentiating LKD from BCL.

METHODS

We compared imaging, clinical, and laboratory data of patients with KD and BCL. We included patients admitted to a single tertiary center between January 2015 and July 2018.

RESULTS

We evaluated data from 51 patients with LKD, 63 with BCL, and 218 with typical KD. Ultrasound imaging revealed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in both LKD and BCL patients. On the other hand, computed tomography (CT) showed more abscesses in patients with BCL. Patients with LKD were younger and showed higher systemic and hepatobiliary inflammatory markers and pyuria than BCL patients. In multivariable logistic regression, younger age and higher C-reactive protein (CRP) retained independent associations with LKD. A comparison of the echocardiographic findings in LKD and typical KD showed that patients with LKD did not have a higher incidence of coronary artery abnormalities (CAA).

CONCLUSIONS

LKD patients tend to have no abscesses on CT and more elevated systemic hepatobiliary inflammatory markers and pyuria compared to BCL patients. The absence of abscess on CT, younger age, and elevated CRP were the most significant variables differentiating LKD from BCL. There was no difference in CAA between LKD and typical KD.

Keywords: Kawasaki disease, Coronary artery, Computed tomography, Bacterial lymphadenitis

INTRODUCTION

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute vasculitis characterized by high, unremitting fever with five primary symptoms. Coronary artery abnormalities (CAA) occur in about 20% of cases of untreated KD.

1) Of the five diagnostic criteria, cervical lymphadenopathy is the least common.

2) However, KD occasionally presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy before other clinical signs appear.

3)4) It is difficult to distinguish cervical-lymphadenopathy-first-presenting Kawasaki disease (LKD) from bacterial cervical lymphadenitis (BCL), so LKD may be misdiagnosed as BCL. These similarities have led to delays in diagnosis, which are reportedly associated with CAA.

5) As there is no specific test for LKD, its diagnosis is uncertain if either no other clinical symptoms appear or if a CAA is not identified, and it remains difficult to differentiate between LKD and BCL. In previous studies comparing LKD and BCL, LKD patients had multiple enlarged firm nodes, high absolute band counts, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) values.

5) Meanwhile, in studies comparing LKD and KD, some have suggested that LKD is associated with higher incidence of CAA and additional intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG),

3) while other studies have shown no difference in CAA or additional IVIG between the two groups.

5)6)7)8)

The authors previously published a comparison of LKD and KD

7) showing that LKD patients present at an older age and have higher CRP values than those with KD, but also that there is no statistical difference in CAA between the two. The current study aimed to compare the initial imaging, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of LKD and BCL to identify useful factors for early diagnosis of LKD and differential diagnosis from BCL to avoid complications that result from delayed treatment of KD.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed medical records (echocardiography, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) findings, and laboratory findings) of patients admitted to Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital for KD and BCL between January 2015 and July 2018. We included patients admitted with KD and treated with IVIG and aspirin and patients admitted with BCL and treated with antibiotics.

KD is diagnosed when fever lasts for more than five days in the presence of at least four of the following five diagnostic criteria: bilateral nonexudative conjunctival injection; erythema of the oral and pharyngeal mucosa with strawberry tongue and red, cracked lips; edema and erythema of the hands and feet; polymorphous rash (including BCG site erythema); and nonsuppurative cervical lymphadenopathy, usually unilateral, with node size >1.5 cm.

1)

LKD is diagnosed in patients who show only fever and cervical lymphadenopathy before other clinical signs of KD appear.

9)10)11)

BCL is defined as acute cervical lymphadenitis in which antibiotic treatment improves fever symptoms; alternatively, bacterial identification can occur through aspiration or surgical biopsy. We excluded chronic lymphadenitis and cervical lymphadenitis without fever

5) from this study.

We divided all subjects into LKD, KD excluding LKD (typical KD), and BCL and compared LKD with BCL and LKD with typical KD.

We analyzed the following data for all patients: imaging findings (ultrasound and CT for cervical lymphadenopathy); clinical data (age, sex, height, weight, unilateral/bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, days of fever before treatment, total duration of fever); and laboratory findings (white blood cell [WBC] count, hemoglobin [Hb], platelet count, neutrophil %, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], CRP, brain natriuretic peptide [BNP], total protein, albumin, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, aspartate transaminase [AST], alanine transaminase [ALT], gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT], and presence of pyuria). We also compared echocardiography and rates of resistance to initial course of IVIG performed during hospitalization of all KD patients.

We reviewed the ultrasound and CT reports of patients with LKD and BCL; a single pediatric radiologist interpreted all images. We classified the location according to whether the cervical lymphadenopathy was unilateral or bilateral and the group of nodes according to whether it had a single dominant mass or multiple enlarged lymph nodes. We also identified abscesses and measured the maximum lymph node diameter.

We analyzed the initial echocardiography for all patients with KD. We used the Dallaire et al.

12) formula to calculate the Z-score of the left main coronary artery (LMCA), left anterior descending artery (LAD), left circumflex artery (LCx), proximal right coronary artery (pRCA), mid right coronary artery (mRCA), and distal right coronary artery (dRCA) using the square root of body surface area. We defined CAA as Z-score ≥ 2.5.

1)

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital approved this study (IRB number: 2018-07-009-001).

We used an independent two-sample t-test to compare continuous variables and a Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables. Using the Spearman rho square, we analyzed univariate correlations between each variable and the diagnostic outcome. We used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate whether the variables of age, Hb, platelet count, neutrophil %, ESR, CRP, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, ALT, GGT, and presence of pyuria could differentiate LKD from BCL. In addition, we used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate whether the variables of age, neutrophil %, ESR, and CRP could differentiate LKD from typical KD. Any p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We performed statistical analysis with SPSS 24.

RESULTS

From January 2015 to July 2018, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital admitted and treated 269 patients with KD. Of these, 51 were diagnosed with LKD; during the same period, 63 patients with BCL were admitted and treated.

LKD vs. BCL

Comparing LKD and BCL on ultrasound, we observed unilateral cervical lymphadenopathy in 11 patients (39%) with LKD and in 20 patients (34%) with BCL. Multiple enlarged lymph nodes were observed in 26 patients (93%) with LKD and in all 58 patients (100%) with BCL. In both groups, multiple enlarged lymph nodes were more common than a single dominant mass, but multiple enlarged lymph nodes were more frequent in BCL than in LKD. We observed abscesses in two patients (7%) with LKD and in 13 patients (22%) with BCL. BCL patients showed abscesses more frequently on ultrasound, but there was no statistical difference between the two groups. Maximum lymph node diameter showed no difference between the two groups.

Of the 51 LKD patients, 27 underwent ultrasonography, one underwent CT, and one underwent both ultrasound and CT. Of the 63 BCL patients, 51 underwent ultrasonography, one underwent CT, and 11 underwent both ultrasound and CT.

Comparing LKD and BCL on CT, we observed unilateral cervical lymphadenopathy in seven patients (58%) with BCL but none (0%) in LKD patients. We observed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in two patients (100%) with LKD and in eight patients (67%) with BCL. An abscess was observed in nine patients (75%) with BCL, but no abscesses were observed (0%) in those with LKD (

Figure 1). There was no difference in maximum lymph node diameter between the two groups (

Table 1).

| Figure 1(A) Neck computed tomography image performed in a patient with lymphadenopathy-first-presenting Kawasaki disease; white arrow indicates multiple enlarged lymph nodes without abscess. (B) Neck computed tomography image performed in a patient with bacterial cervical lymphadenitis; white arrow indicates multiple enlarged lymph nodes with internal low density, suggesting abscess.

|

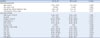

Table 1

Imaging studies of LKD and BCL patients.

|

Variables |

LKD (n=51) |

BCL (n=63) |

p-value |

|

Ultrasound, n |

28 |

58 |

|

|

Location |

|

|

0.664 |

|

|

Unilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, n (%) |

11 (39) |

20 (34) |

|

|

Bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, n (%) |

17 (61) |

38 (66) |

|

Lymph node |

|

|

0.039 |

|

|

Single dominant mass, n (%) |

2 (7) |

0 (0) |

|

|

Multiple enlarged lymph nodes, n (%) |

26 (93) |

58 (100) |

|

Presence of abscess, n (%) |

2 (7) |

13 (22) |

0.080 |

|

Maximum lymph node diameter, mm |

22.55 ± 5.08 |

23.71 ± 8.10 |

0.421 |

|

Computed tomography, n |

2 |

12 |

|

|

Location |

|

|

0.127 |

|

|

Unilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, n (%) |

0 (0) |

7 (58) |

|

|

Bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, n (%) |

2 (100) |

5 (42) |

|

Lymph node |

|

|

0.334 |

|

|

Single dominant mass, n (%) |

0 (0) |

4 (33) |

|

|

Multiple enlarged lymph nodes, n (%) |

2 (100) |

8 (67) |

|

Presence of abscess, n (%) |

0 (0) |

9 (75) |

0.040 |

|

Maximum lymph node diameter, mm |

20.40 ± 3.68 |

23.09 ± 11.35 |

0.715 |

LKD patients were younger than BCL patients. The number of days of fever before treatment and total fever duration were longer for LKD than BCL (

Table 2).

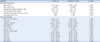

Table 2

Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of LKD and BCL patients.

|

Variables |

LKD (n=51) |

BCL (n=63) |

p-value |

|

Clinical characteristics |

|

|

|

|

Age, months |

47.16 ± 19.54 |

73.1 ± 48.5 |

0.038*

|

|

Sex, male, n (%) |

30 (59) |

34 (54) |

0.603 |

|

Days of fever before treatment, days |

5.94 ± 1.45 |

3.9 ± 3.3 |

< 0.001*

|

|

Total duration of fever, days |

7.65 ± 1.71 |

7.3 ± 4.4 |

0.031*

|

|

Laboratory findings |

|

|

|

|

WBC count, ×103/mm2

|

15.66 ± 5.07 |

14.50 ± 8.82 |

0.384 |

|

Hb, g/dL |

11.31 ± 0.93 |

12.04 ± 1.09 |

< 0.001*

|

|

Platelet, ×103/mm2

|

361.43 ± 107.08 |

312.22 ± 128.81 |

0.031*

|

|

Neutrophil, % |

74.07 ± 13.47 |

61.95 ± 18.83 |

< 0.001*

|

|

ESR, mm/hr |

67.35 ± 20.65 |

49.39 ± 26.35 |

< 0.001*

|

|

Pyuria, n (%) |

14 (27) |

7 (11) |

0.028*

|

|

Bilirubin, total, mg/dL |

0.71 ± 0.97 |

0.41 ± 0.35 |

0.040*

|

|

AST, IU/L |

134.27 ± 304.57 |

37.37 ± 39.12 |

0.028*

|

|

ALT, IU/L |

118.67 ± 234.23 |

24.87 ± 54.84 |

0.007*

|

|

GGT, IU/L |

64.98 ± 99.055 |

20.30 ± 48.34 |

0.004*

|

|

CRP, mg/L |

93.12 ± 43.81 |

58.20 ± 44.86 |

< 0.001*

|

|

BNP, pg/mL |

76.76 ± 129.14 |

26.92 ± 17.21 |

0.231 |

Both LKD and BCL showed leukocytosis, but the neutrophil percentage was higher in LKD than in BCL. ESR, CRP, AST, ALT, and GGT were higher in LKD than in BCL. In LKD, pyuria was more frequent than in BCL. BNP was higher in LKD than in BCL, but the difference was not statistically significant (

Table 2).

In multivariable logistic regression, younger age (odds ratio [OR]: 0.955, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.921–0.991) and higher CRP (OR: 1.027, 95% CI: 1.005–1.049) retained an independent association with LKD compared to BCL.

LKD vs. typical KD

Comparing LKD with typical KD on initial echocardiography, there was no significant difference in Z-score of coronary arteries for LMCA, LAD, LCx, pRCA, mRCA, and dRCA (

Table 3). The incidence of CAA was not statistically different between the two groups (

Figure 2).

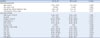

Table 3

Echocardiographic findings of LKD and typical KD patients.

|

|

LKD (n=51) |

Typical KD (n=218) |

p-value |

|

Coronary artery Z-score |

|

|

|

|

LMCA |

0.51 ± 0.86 |

0.6 ± 1.01 |

0.557 |

|

LAD |

1.17 ± 1.50 |

1.33 ± 1.46 |

0.489 |

|

LCx |

0.17 ± 0.91 |

0.31 ± 1.17 |

0.422 |

|

Proximal RCA |

0.09 ± 1.19 |

0.29 ± 1.10 |

0.263 |

|

Mid RCA |

0.03 ± 1.15 |

0.25 ± 1.22 |

0.471 |

|

Distal RCA |

−0.79 ± 1.79 |

−0.81 ± 1.02 |

0.962 |

|

Coronary artery abnormality, n (%) |

7 (14) |

33 (15) |

0.799 |

| Figure 2Echocardiographic images of a left coronary artery in parasternal short axis view. (A) In a patient with lymphadenopathy-first-presenting Kawasaki disease, the left coronary artery shows ectasia. (B) In a patient with typical Kawasaki disease, a marked dilated and tortuous coronary artery was revealed.

|

LKD patients were older than those with typical KD. The number of days of fever before treatment showed no statistical difference between the two groups, but total fever duration was longer for LKD patients. Resistance to initial course of IVIG was more common among LKD patients, but there was no statistical difference between the two groups. There was no significant difference in incomplete KD percentage between the two groups (

Table 4).

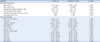

Table 4

Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of LKD and typical KD patients.

|

Variables |

LKD (n=51) |

Typical KD (n=218) |

p-value |

|

Clinical characteristics |

|

|

|

|

Age, months |

47.16 ± 19.54 |

27.78 ± 20.81 |

< 0.001*

|

|

Sex, male, n (%) |

30 (59) |

128 (59) |

0.989 |

|

Days of fever before treatment, days |

5.94 ± 1.45 |

5.61 ± 1.37 |

0.126 |

|

Total duration of fever, days |

7.65 ± 1.71 |

6.86 ± 2.13 |

0.015*

|

|

Resistance to initial IVIG course, n (%) |

13 (26) |

31 (14) |

0.056 |

|

Incomplete KD, n (%) |

4 (8) |

11 (5) |

0.433 |

|

Laboratory findings |

|

|

|

|

WBC count, ×103/mm2

|

15.66 ± 5.07 |

14.76 ± 4.67 |

0.225 |

|

Hb, g/dL |

11.31 ± 0.93 |

11.34 ± 0.92 |

0.846 |

|

Platelet, ×103/mm2

|

361.43 ± 107.08 |

377.01 ± 108.28 |

0.355 |

|

Neutrophil, % |

74.07 ± 13.47 |

64.04 ± 14.42 |

< 0.001*

|

|

ESR, mm/hr |

67.35 ± 20.65 |

54.69 ± 19.75 |

< 0.001*

|

|

Pyuria, n (%) |

14 (27) |

91 (42) |

0.060 |

|

Bilirubin, total, mg/dL |

0.71 ± 0.97 |

0.61 ± 0.63 |

0.392 |

|

AST, IU/L |

134.27 ± 304.57 |

98.54 ± 171.39 |

0.422 |

|

ALT, IU/L |

118.67 ± 234.23 |

101.27 ± 154.52 |

0.615 |

|

GGT, IU/L |

64.98 ± 99.055 |

76.95 ± 96.00 |

0.427 |

|

CRP, mg/L |

93.12 ± 43.81 |

72.28 ± 46.70 |

0.004*

|

|

BNP, pg/mL |

76.76 ± 129.14 |

103.10 ± 166.06 |

0.296 |

Both LKD and typical KD patients showed leukocytosis, but the neutrophil percentage was higher for LKD than BCL. ESR and CRP were higher for LKD than typical KD. There was no difference in pyuria or BNP between the two groups (

Table 4).

In multivariable logistic regression, older age (OR: 1.043, 95% CI: 1.026–1.059) and higher ESR (OR: 1.032, 95% CI: 1.015–1.050) retained an independent association with LKD compared to typical KD.

DISCUSSION

Imaging studies, including ultrasound and CT, are useful tools for distinguishing KD and BCL.

1) Several studies have reported that retropharyngeal edema is common in KD.

13)14)15) Comparing LKD and BCL, Kanegaye et al.

5) reported that multiple enlarged lymph nodes are common in KD. In contrast, phlegmon and abscesses are more common in BCL, and retropharyngeal edema is common in both LKD and BCL. Nozaki et al.

16) reported that LKD showed multiple enlarged lymph nodes more frequently and poorly circumscribed margins and non-visualization of the hilum less frequently than BCL on ultrasound. In addition, LKD showed more frequent retropharyngeal edema than BCL on CT. Our study showed that abscesses are more common in BCL than in LKD on CT. However, our study also showed that multiple enlarged lymph nodes are common in both LKD and BCL on ultrasound, which suggests that multiple enlarged lymph nodes may not differentiate between LKD and BCL. Previous studies and this study suggest that imaging is not an absolute factor to distinguish BCL from LKD. The lack of testing in all patients is a limitation of this study, and studies involving more imaging tests are needed.

LKD is often difficult to differentiate from BCL when other KD symptoms appear late, and it is important to make an early diagnosis because it can be associated with CAA.

3) Kanegaye et al.

5) reported that LKD patients presented with older age, lower WBC and platelet counts, and higher absolute band count, ESR, CRP, ALT, and GGT than BCL patients. Among these variables, smaller lymph nodes, lower WBC, high absolute band count, and higher CRP are strongly associated with LKD. Similarly, our study showed higher ESR, CRP, ALT, and GGT in LKD than in BCL. Meanwhile, there was no difference in WBC count, and LKD showed younger age and lower platelet counts.

LKD patients showed older age, higher neutrophil percentage, and higher CRP than typical KD patients. Yanagi et al.

4) reported that LKD patients showed older age and higher WBC count, neutrophil counts, AST, and CRP than typical KD patients. Kubota et al.

6) reported that LKD patients showed older age and higher CRP than typical KD patients, but there was no difference in WBC count. Nomura et al.

3) reported that LKD patients showed older age and higher WBC count, neutrophil percentage, and CRP. Our previous study

7) also reported that LKD patients showed older age and higher neutrophil count and CRP, but there was no difference in WBC count. Jun et al.

8) reported that LKD patients showed older age, and higher neutrophil count and CRP but no difference in WBC count. In the present study, age, neutrophil percentage or count, and CRP showed similar results to those described above. However, WBC count was lower in LKD than in typical KD; none of the previous studies showed such a result. There are many reasons for the varying results among studies; they may be due to local and environmental diversity of the patients recruited by the research centers. Therefore, we expect to obtain more accurate results by conducting large-scale studies on more patients in the future. It is possible that neutrophil percentage or count is more important than WBC count in distinguishing LKD from BCL.

Nomura et al.

3) reported that LKD is associated with increased risk of CAA and additional IVIG. However, there was no difference in CAA or IVIG resistance between LKD and typical KD in the present study; these results suggest that clinical interest in LKD has increased, leading to more actively diagnosis and treatment. There also was no statistically significant difference in the number of days of fever before treatment between LKD and typical KD in this study. This may be due to clinicians’ increased interest in LKD in recent years, with more accurate diagnoses and timely treatment leading to reduced incidence of CAA and additional IVIG.

Our study has several limitations. In the study, all KD patients were hospitalized and treated. However, since we confined BCL to only hospitalized patients, there may have been a selection bias. Since bacteria were culture-proven in only 8% of the cases defined as BCL, some of them may not have been true bacterial lymphadenitis, which may have affected the imaging results. In addition, not all patients underwent an imaging study, and there was no indication whether to perform ultrasound or CT. In this study, the clinician decided whether to perform the imaging study and whether to perform ultrasound or CT based on personal experience. A future prospective study with ultrasound and CT will be able to strengthen the statistical basis.

In conclusion, LKD patients typically have no evidence of abscess on CT and more elevated systemic and hepatobiliary inflammatory markers and pyuria than BCL patients. In our study, 51 (19%) of the 269 KD patients were LKD. To provide accurate diagnosis and timely treatment, clinicians should consider LKD when patients with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy are young and have elevated CRP with no evidence of abscess on CT. In addition, clinicians should educate caregivers about the clinical features of KD and instruct patients to revisit the clinic to reevaluate KD.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download