1. Arabi YM, Balkhy HH, Hayden FG, Bouchama A, Luke T, Baillie JK, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(6):584–594.

2. Hijawi B, Abdallat M, Sayaydeh A, Alqasrawi S, Haddadin A, Jaarour N, et al. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East Mediterr Health J. 2013; 19 Suppl 1:S12–S18.

4. Kang CK, Song KH, Choe PG, Park WB, Bang JH, Kim ES, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of spreaders of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus during the 2015 outbreak in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(5):744–749.

6. Conzade R, Grant R, Malik MR, Elkholy A, Elhakim M, Samhouri D, et al. Reported direct and indirect contact with dromedary camels among laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV cases. Viruses. 2018; 10(8):E425.

7. Choi WS, Kang CI, Kim Y, Choi JP, Joh JS, Shin HS, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of Middle East respiratory syndrome in the Republic of Korea. Infect Chemother. 2016; 48(2):118–126.

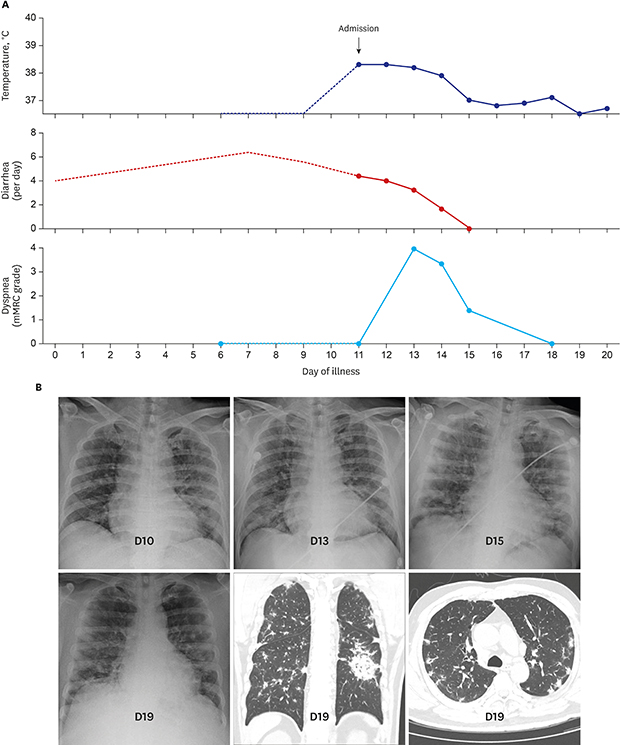

8. Kim ES, Choe PG, Park WB, Oh HS, Kim EJ, Nam EY, et al. Clinical progression and cytokine profiles of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31(11):1717–1725.

9. Chan JF, Chan KH, Choi GK, To KK, Tse H, Cai JP, et al. Differential cell line susceptibility to the emerging novel human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012: implications for disease pathogenesis and clinical manifestation. J Infect Dis. 2013; 207(11):1743–1752.

10. Corman VM, Albarrak AM, Omrani AS, Albarrak MM, Farah ME, Almasri M, et al. Viral shedding and antibody response in 37 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 62(4):477–483.

11. Wu J, Yi L, Zou L, Zhong H, Liang L, Song T, et al. Imported case of MERS-CoV infection identified in China, May 2015: detection and lesson learned. Euro Surveill. 2015; 20(24):21158.

12. Zhou J, Li C, Zhao G, Chu H, Wang D, Yan HH, et al. Human intestinal tract serves as an alternative infection route for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Sci Adv. 2017; 3(11):eaao4966.

13. Kligerman SJ, Franks TJ, Galvin JR. From the radiologic pathology archives: organization and fibrosis as a response to lung injury in diffuse alveolar damage, organizing pneumonia, and acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia. Radiographics. 2013; 33(7):1951–1975.

14. Ajlan AM, Ahyad RA, Jamjoom LG, Alharthy A, Madani TA. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: chest CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014; 203(4):782–787.

15. El Zein S, Khraibani J, Zahreddine N, Mahfouz R, Ghosn N, Kanj SS. Atypical presentation of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in a Lebanese patient returning from Saudi Arabia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2018; 12(9):808–811.

16. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. Updated 2015. Accessed Oct 12, 2018.

http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/178529.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download