This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Purpose

Chronic testicular pain remains an important challenge for urologists. At present there are many treatment modalities available for chronic orchialgia. Some patients remain in pain despite a conservative treatment. Microsurgical denervation of spermatic cord appears to be successful in relieving pain in patients who fail conservative management. We assessed the long-term efficacy, complications and patient perceptions of microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord in the treatment of chronic orchialgia.

Materials and Methods

A prospective study was conducted from January 2007 to January 2016 which included men with testicular pain of >3 months duration, failure of conservative management, persistent of pain for >3 months after treating the underlying cause. Total 48 patients with 62 testicular units (14 bilateral) showed the response to spermatic cord block and underwent microsurgical denervation of spermatic cord.

Results

Out of 62 testicular units (14 bilateral) which were operated, complete 2 years follow-up data were available for 38 testicular units. Out of these 38 units, 31 units (81.57%) had complete pain relief, 4 units (10.52%) had partial pain, and 3 units (7.89%) were non-responders. Complications were superficial wound infection in 3 units (4.83%), hydrocele in 2 units (3.22%), subcutaneous seroma in 2 units (3.22%), and an incisional hematoma in 1unit (1.61%) out of 62 operated testicular units.

Conclusions

Idiopathic chronic orchialgia remains a difficult condition to manage. If surgery is considered, microsurgical denervation of spermatic cord should be considered as a first surgical approach to get rid of pain and sparing the testicle.

Go to :

Keywords: Chronic pain, Denervation, Pain management, Scrotum, Spermatic cord, Testis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic orchialgia is defined as an intermittent or constant testicular pain, unilateral or bilateral, lasting for over 3 months that interferes significantly with the patient's daily activities [

1]. Chronic orchalgia can be a problem for both patients and urologist. Many of these patients will visit multiple physicians during course of their treatment. Although the severity of pain is mild to moderate, but chronicity of the condition presents a quality of life issue. Managing patient with chronic orchalgia is thus challenging for urologist. Chronic orchialgia or chronic testicular pain is multifactorial. Causative factors for chronic orchialgia may include infection, torsion, tumor, inguinal hernia, hydrocele, spermatocele, varicocele, referral pain, trauma, and previous operations,

e.g., Vasectomy or inguinal hernia repair. Nearly 25% of patients with chronic orchialgia have no obvious cause for the pain and therefore can be called idiopathic chronic orchialgia [

2]. The definite pathophysiology of pain is not clearly understood. A commonly accepted theory is hypersensitivity of the sensory pain fibers in the peripheral neural pathways. Commonly affected nerves are ilioinguinal, genital branch of the genitofemoral and pudendal nerves. Hypersensitivity of pain sensory fibers may occur due to neural plasticity [

234]. Another possible explanation for hypersensitivity in these fibers is Wallerian degeneration in these peripheral nerves [

5]. Study found a high density of nerves with Wallerian degeneration in three primary locations 1) cremasteric muscle fibers, 2) perivasal tissues/vasal sheath, 3) posterior peri-arterial lipomatous tissue. This is termed as ‘trifecta nerve complex’ [

6]. Ablation of this complex is postulated as the possible basis for the success of microsurgical denervation of spermatic cord (MDSC) as a treatment for idiopathic chronic orchalgia. This is a method of targeted denervation.

The goal of MDSC is to 1) alleviate chronic orchialgia, 2) sparing the testicle, 3) preserving both its physiologic and psychological roles [

6].

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective study was conducted in the Department of Urology, Ruby Hall Clinic from January 2007 to January 2016.

1. Ethics statement

Declaration of Helsinki (Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects) were followed during study and all human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality.

2. Inclusion criteria

Patients with testicular pain of more than 3 months duration with failed conservative management.

3. Exclusion criteria

Identification of causative factor for orchalgia e.g., varicocele etc.

A detailed medical history was taken in all patients presenting with chronic orchalgia. The history includes type of pain, duration of pain, previous genital infection, any urinary complains, pain at time of ejaculation, back injury, pain or trauma, psychiatric disorders, analgesic use, and prior surgery in the pelvis, inguinal region, or scrotum, etc. Detail examination was carried out in all patients in a standing and supine position to evaluate abdomen and pelvis, testis, epididymis, vas deferens. Pain was rated on visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 10. A digital rectal exam was carried out to evaluate prostate. Laboratory evaluation includes urinalysis, urine culture, Expressed Prostatic Secretion culture and semen culture. All patients underwent duplex scrotal ultrasonography (USG) and abdominal USG (USG kidney ureter bladder region with post void residual urine) to exclude structural abnormalities. Computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen and/or magnetic resonance imaging of spine were done in men with backache or any neurological findings.

Patients which were diagnosed as chronic orchalgia were initially managed conservatively with simple noninvasive and nontoxic approaches including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics, particularly when there is evidence of infection. In our population, patients with conditions like chronic prostatitis are often managed with inappropriate antibiotic regimens at peripheral health centers. So, they were given antibiotics for 4 weeks. However, evidence for an empiric trial of antibiotics in this scenario is lacking. Patients who did not respond to conservative management and when no reversible cause of the pain was identified, they were labeled as patients with idiopathic chronic orchiagia. In these patients spermatic cord block was performed at the pubic tubercle area with 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine. Out of 87 testicular units of idiopathic chronic orchialgia, 62 testicular units responded to test dose of 0.5% bupivacaine.

MDSC was offered to the patients who had partial pain relief with test dose spermatic cord block. Special consent was taken from all the patients regarding outcome of surgery including failure to alleviate the pain, infection, bleeding, testicular loss, hypogonadism, and infertility. In patients with prior history of vasectomy, the vas was divided again to ensure that any neural fibers within and on the vas are destroyed; vasectomy was not done in young patients (under 40 years) because fertility was a matter. Patients were offered unilateral or bilateral MSDSC, depending on the side of pain, 48 men with 62 testicular units (14 bilateral) with chronic idiopathic orchialgia underwent MDSC. Among 34 unilateral cases, three patients had history of left inguinal varicocelectomy by open surgery and 4 patients had history of hydrocelectomy. Among 14 bilateral testicular orchialgia patients; 4 had history of bilateral open inguinal varicocelectomy and two patients had history of vasectomy. Technique wise there was no difference in unilateral or bilateral MSDCD surgery.

Postoperatively pain relief was assessed after 1 week, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. Patients were categorized as complete responders with postoperative VAS pain score less than 3 or reduction of VAS score by more than 2 points, partial responders (reduction in VAS pain score by at least 1 point) and no responders (no reduction in VAS pain score). Parameters evaluated were mean age of patients, mean duration of pain, number of testicular units affected, preoperative VAS pain score, operative time, postoperative VAS pain score at 1 week, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years, and postoperative complications (

Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1Flow chart showing study protocol.

|

4. Microsurgical denervation of spermatic cord technique

MDSC Surgery was done with operating microscope. Inguinal incision was made on appropriate side, exposing the external inguinal ring. The spermatic cord was elevated and brought to rest on a five eighths–inch Penrose drain. Anterior spermatic cord fascia was opened for 3 to 4 cm to expose the cord contents. The internal spermatic veins are ligated and divided. As many lymphatic's as possible are identified and spared; this is to prevent hydrocele formation. Electro-cautery was used to divide all of the remaining cremasteric musculature and spermatic cord fascia. The vas was stripped of its fascia-covered outer layer to ablate afferent nerve pathways. In those with prior vasectomy, the vas is divided again to ensure that any neural fibers within and on the vas are destroyed. The cord is placed back into its original position and the wound closed in layers. This technique is almost same as described by Levine [

7].

Go to :

RESULTS

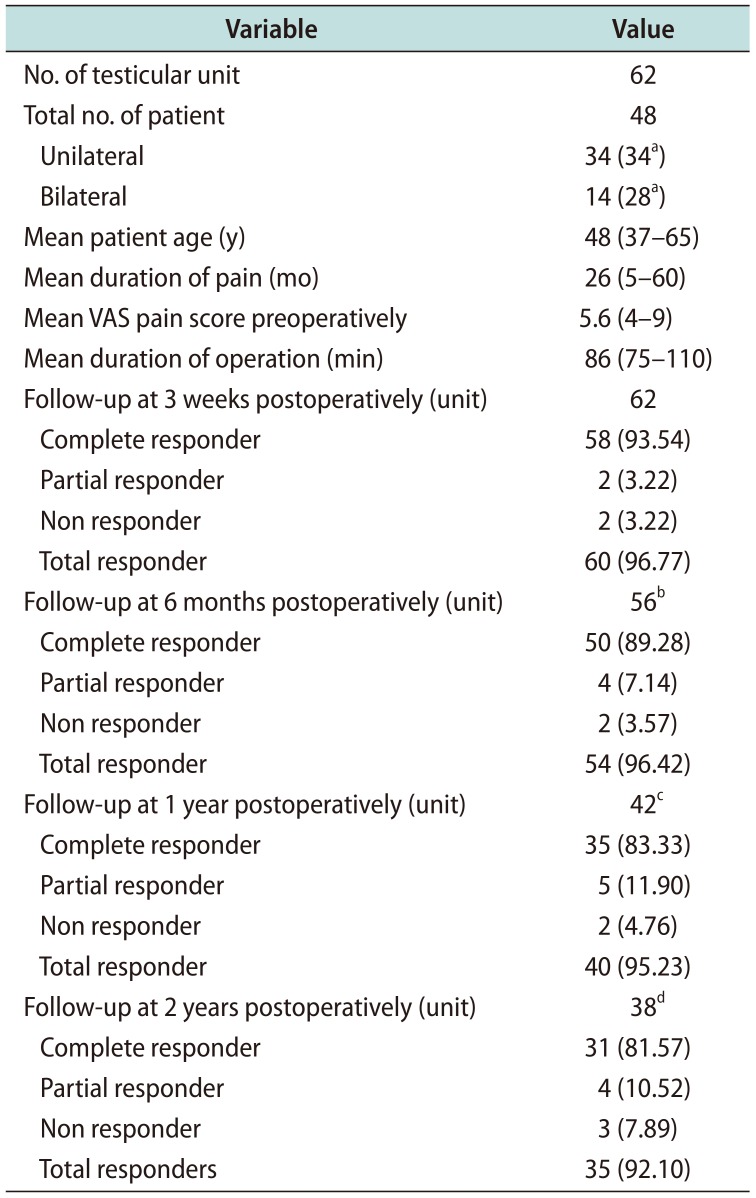

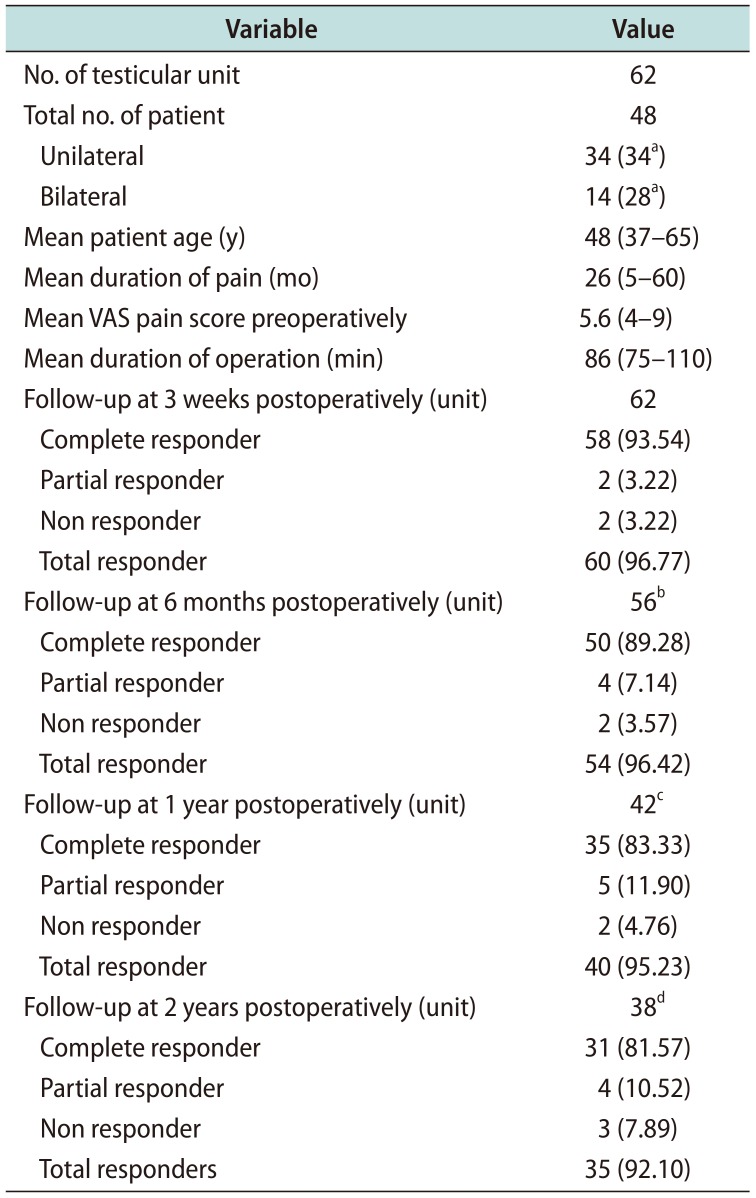

Between January 2007 and January 2016, 48 men with 62 testicular units (14 bilateral) with chronic orchialgia underwent MDSC. Mean patient age was 48 years (range, 37–65 years). The preoperative duration of orchialgia ranged from 5 to 60 months (mean, 26 months). Mean preoperative VAS pain score were 5.6 (range, 4–9); mean operative time 86 minutes (range, 75–110 minutes). At 3 weeks postoperatively, 62 units had come for follow-up out of which complete pain relief was seen in 58 units (93.54%), partial pain relief was seen in 2 units (3.22%), 2 units (3.22%) were non responders. However no one had worsening of pain postoperatively. At 6 months postoperatively, 56 units had come for follow-up and 6 units were lost for follow-up. Out of these 56 units, 50 units (89.28%) had complete pain relief, 4 units (7.14%) had partial pain of lesser severity, and 2 units (3.57%) were non responders. At 1 year postoperatively, 42 units had come for follow-up and additional 14 units were lost for follow-up. Out of these 42 units, 35 units (83.33%) had complete pain relief, 5 units (11.90%) had partial pain relief, and 2 units (4.76%) were non responders. At 2 years postoperatively, 38 units had come for follow-up and additional 4 units were lost for follow-up.

Hence, complete data was available for these 38 testicular units/31 patients only. Out of these 38 units, 31 units (81.57%) had complete pain relief, 4 units (10.52%) had partial pain, and 3 units (7.89%) were non responders (

Table 1).

Table 1

Demographic data and results

|

Variable |

Value |

|

No. of testicular unit |

62 |

|

Total no. of patient |

48 |

|

Unilateral |

34 (34a) |

|

Bilateral |

14 (28a) |

|

Mean patient age (y) |

48 (37–65) |

|

Mean duration of pain (mo) |

26 (5–60) |

|

Mean VAS pain score preoperatively |

5.6 (4–9) |

|

Mean duration of operation (min) |

86 (75–110) |

|

Follow-up at 3 weeks postoperatively (unit) |

62 |

|

Complete responder |

58 (93.54) |

|

Partial responder |

2 (3.22) |

|

Non responder |

2 (3.22) |

|

Total responder |

60 (96.77) |

|

Follow-up at 6 months postoperatively (unit) |

56b

|

|

Complete responder |

50 (89.28) |

|

Partial responder |

4 (7.14) |

|

Non responder |

2 (3.57) |

|

Total responder |

54 (96.42) |

|

Follow-up at 1 year postoperatively (unit) |

42c

|

|

Complete responder |

35 (83.33) |

|

Partial responder |

5 (11.90) |

|

Non responder |

2 (4.76) |

|

Total responder |

40 (95.23) |

|

Follow-up at 2 years postoperatively (unit) |

38d

|

|

Complete responder |

31 (81.57) |

|

Partial responder |

4 (10.52) |

|

Non responder |

3 (7.89) |

|

Total responders |

35 (92.10) |

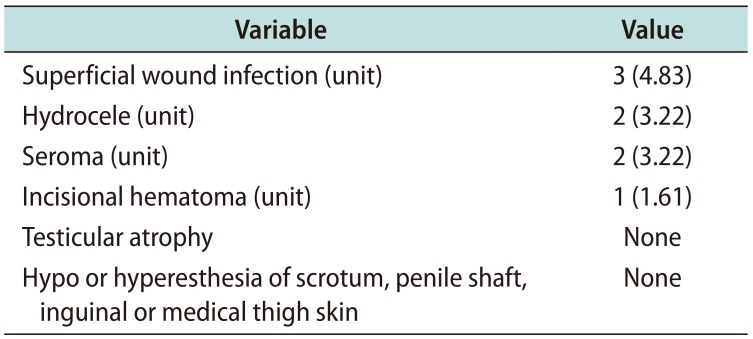

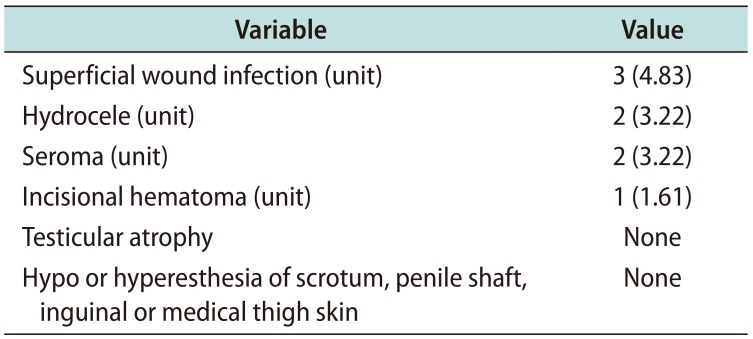

Complications included superficial wound infection in 3 units (4.83%) which responded to oral antibiotics and local wound care, hydrocele in 2 units (3.22%), subcutaneous seroma that drained spontaneously in 2 units (3.22%), and an incisional hematoma in 1 unit (1.61%). There were no complaints of hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia of the scrotum, penile shaft, inguinal or medial thigh skin. No testicular atrophy was noted in any patients (

Table 2).

Table 2

Rate of complications noted in this study

|

Variable |

Value |

|

Superficial wound infection (unit) |

3 (4.83) |

|

Hydrocele (unit) |

2 (3.22) |

|

Seroma (unit) |

2 (3.22) |

|

Incisional hematoma (unit) |

1 (1.61) |

|

Testicular atrophy |

None |

|

Hypo or hyperesthesia of scrotum, penile shaft, inguinal or medical thigh skin |

None |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Chronic pain associated with genitourinary system is difficult to deal with, as the exact etiopathogenesis is lacking. These chronic pain syndromes mainly includes chronic pelvic pain syndrome, painful bladder syndrome, and interstitial cystitis, chronic testicular pain is a subgroup of chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

Idiopathic chronic orchialgia remains a difficult condition to manage since the cause of pain is not known. There is little published literature about the etiology and pathophysiology of idiopathic chronic orchialgia. Hypersensitivity of the pain sensory fibers in the ilioinguinal, genital branch of the genitofemoral, or pudendal nerves is a postulated theory. This hypersensitivity is because of neural plasticity. The ability of our nervous system, both centrally and peripherally, is to adapt when damaged or inflamed by altering gene expression. It can change the structure of the nerve or adapt the chemical and/or receptor profile. This can lead to lower threshold potentials in the neuropathic pathways [

37]. Another reason for hypersensitivity in these fibers is Wallerian degeneration. Wallerian degeneration is the auto destruction of the proximal and distal axon, leading to an environment clear of inhibitory debris, and supportive of axon regrowth and functional recovery. Wallerian degeneration initiates immune response. This inflammatory change leads to neural hypersensitivity [

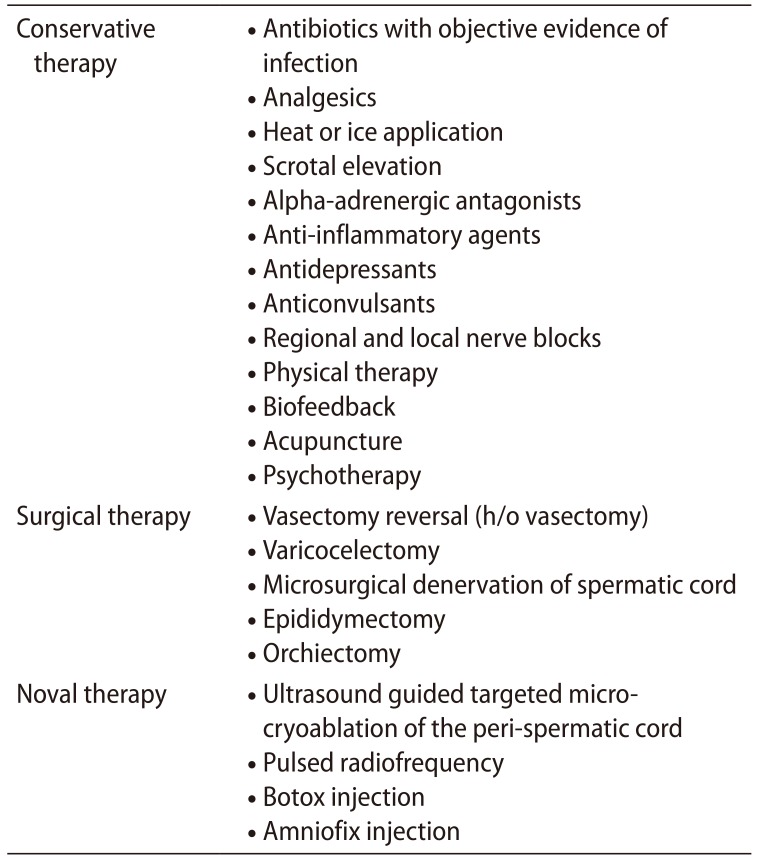

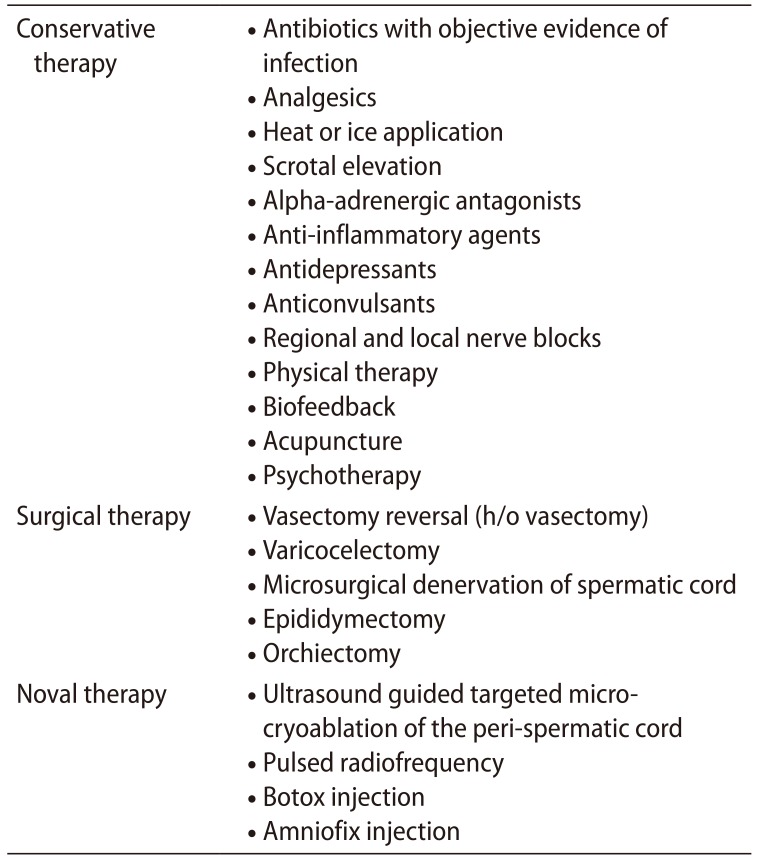

58]. Various modalities which are available for the management of chronic orchalgia are listed in

Table 3 [

910].

Table 3

Various treatment modalities available for management of chronic orchialgia [9102021]

|

Conservative therapy |

· Antibiotics with objective evidence of infection |

|

· Analgesics |

|

· Heat or ice application |

|

· Scrotal elevation |

|

· Alpha-adrenergic antagonists |

|

· Anti-inflammatory agents |

|

· Antidepressants |

|

· Anticonvulsants |

|

· Regional and local nerve blocks |

|

· Physical therapy |

|

· Biofeedback |

|

· Acupuncture |

|

· Psychotherapy |

|

Surgical therapy |

· Vasectomy reversal (h/o vasectomy) |

|

· Varicocelectomy |

|

· Microsurgical denervation of spermatic cord |

|

· Epididymectomy |

|

· Orchiectomy |

|

Noval therapy |

· Ultrasound guided targeted microcryoablation of the peri-spermatic cord |

|

· Pulsed radiofrequency |

|

· Botox injection |

|

· Amniofix injection |

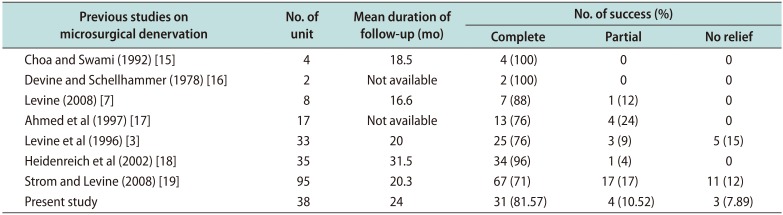

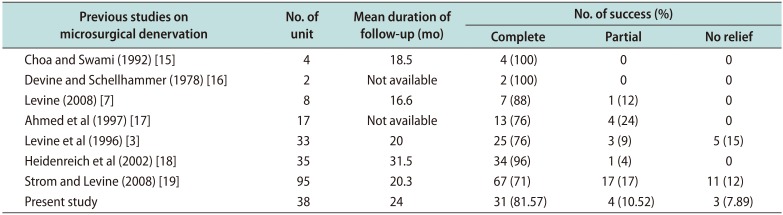

In our study from 2007 to 2016, 48 men with 62 testicular units (14 bilateral) with chronic orchialgia underwent MDSC. In this series, medical therapy had failed in our patients including trials of antibiotics, NSAIDs and/or narcotic analgesics. Some patient had sought relief with alternative medical therapy including regional nerve blocks, physical therapy, psychotherapy or acupuncture. In this study, mean preoperative VAS pain score was 5.6 and mean duration of pain was 26 months. As discussed in results, we had 96.74% responders at 3 weeks postoperatively. Complete data was available for 38 testicular units/31 patients only. Out of these 38 units, 31 units (81.57%) had complete pain relief, 4 units (10.52%) had partial pain, and 3 units (7.89%) were non responders. A comparison between previous and our study is given in (

Table 4) [

371112,

131415]. However, no formal comparison was done with other surgical methods for treating idiopathic chronic orchialgia.

Table 4

Comparison of our study with other studies

|

Previous studies on microsurgical denervation |

No. of unit |

Mean duration of follow-up (mo) |

No. of success (%) |

|

|

|

Complete |

Partial |

No relief |

|

Choa and Swami (1992) [15] |

4 |

18.5 |

4 (100) |

0 |

0 |

|

Devine and Schellhammer (1978) [16] |

2 |

Not available |

2 (100) |

0 |

0 |

|

Levine (2008) [7] |

8 |

16.6 |

7 (88) |

1 (12) |

0 |

|

Ahmed et al (1997) [17] |

17 |

Not available |

13 (76) |

4 (24) |

0 |

|

Levine et al (1996) [3] |

33 |

20 |

25 (76) |

3 (9) |

5 (15) |

|

Heidenreich et al (2002) [18] |

35 |

31.5 |

34 (96) |

1 (4) |

0 |

|

Strom and Levine (2008) [19] |

95 |

20.3 |

67 (71) |

17 (17) |

11 (12) |

|

Present study |

38 |

24 |

31 (81.57) |

4 (10.52) |

3 (7.89) |

Other surgical treatments such as epididymectomy should only be performed when chronic pain localizes only to the epididymis [

116]. Post vasectomy pain syndrome which mimics chronic orchalgia is relieved by vasovasostomy in 69 to 100% cases. But vasovasovasostomy defeats the original intention for doing vasectomy and therefore it is not advisable [

171819]. Orchiectomy is a drastic measure as a treatment for chronic orchalgia. By ablating the testicle, gonadal endocrine function is diminished, and castration may cause psychological consequences. In addition, complete resolution of pain is not guaranteed [

120]. Published series on novel therapy such as USG guided micro cryoablation, Botox injection and amnioflex injection shows variable success rates from 9% to 14% [

21]. Clearly there is not a defined surgical algorithm for treating orchialgia.

According to our experience, MDSC appears to work well. However, there is no control group for comparison in this study. Chronic pain remains a dilemma and as further research provides insight into the mechanisms, new treatments will presumably emerge. In the meantime, MDSC appears to be a reasonable approach to get rid of the pain and spare the testicle. Other benefits of MDSC include stopping chronic drug use, resumption of daily living activities and improving quality of life [

2]

Go to :

CONCLUSIONS

Idiopathic chronic orchialgia remains a difficult condition to manage since the cause of pain is not known. It is vital to realize that the goal of treatment should be complete elimination of pain for better quality of life. Adequate relief of pain should allow patient to return to an active life with a better mechanism to cope with residual pain. A multi-disciplinary approach including pain clinic services and psychologists may be beneficial before considering surgery. If surgery is considered, MDSC should be considered first surgical approach to get rid of pain and spare the testicle.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download