DISCUSSION

The staging of lymphoma after diagnosis is crucial for treatment and prognosis. Extra-nodal involvement is classified as grade 4 lymphoma and affects prognosis [

45678]. PET/CT is an imaging method that has high sensitivity and specificity for detecting extra-nodal involvement and for monitoring response to treatment [

91011]. BMB, which has an important role in the staging of lymphoma, is an invasive method based on the examination of a very small area. In NHL, BMI is seen in 18–36% of aggressive lymphomas and 40–90% of indolent lymphomas [

12]. In HL, BMI is detected in 5–14% of cases [

13].

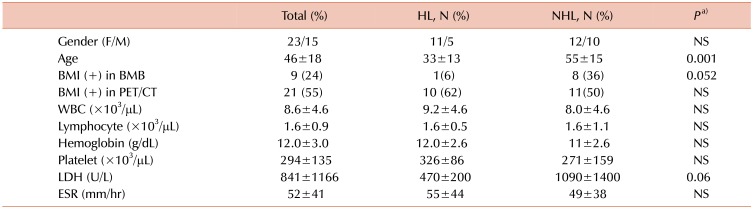

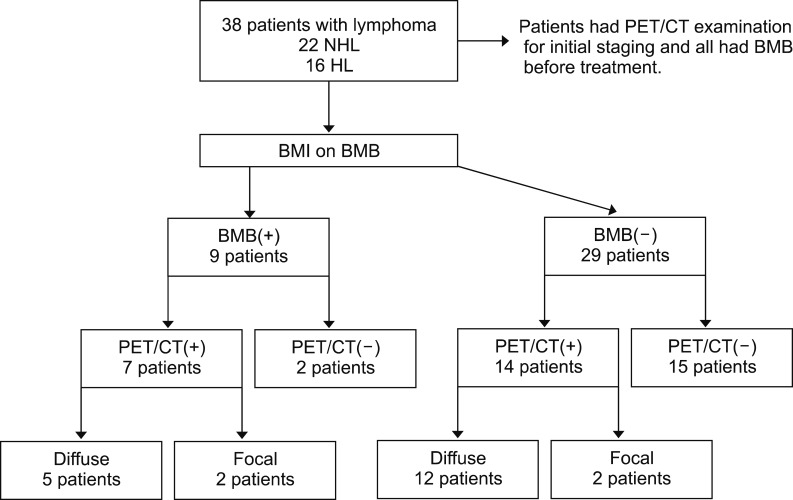

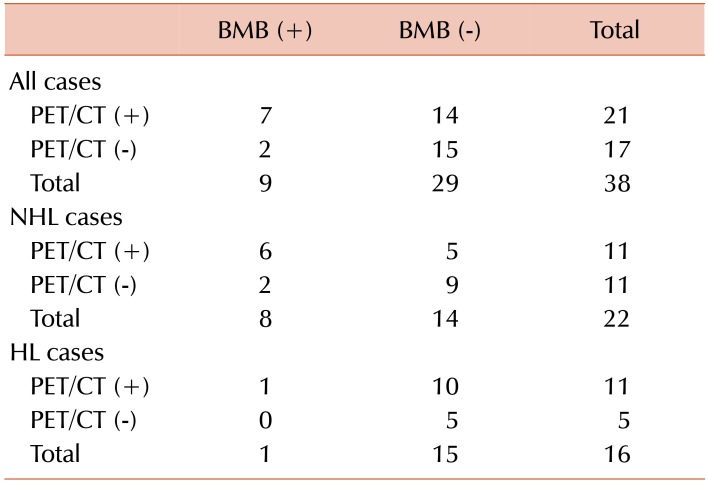

BMI was detected by biopsy in 34% of our cases with NHL and 6% in HL cases. BMI was detected by PET/CT in 50% of patients with NHL and 62% of patients with HL. The rate of BMI detected by PET/CT tended to be higher in cases with HL. As a result, BMI rates tended to be higher in PET/CT than in biopsy. In some cases, mostly patients with HL, PET/CT, the bone marrow revealed false positives. FDG PET/CT can show widespread, increased bone marrow activity in the setting of diffuse BMI or peripheral red blood cell destruction, such as in hypersplenism and hemolytic anemia [

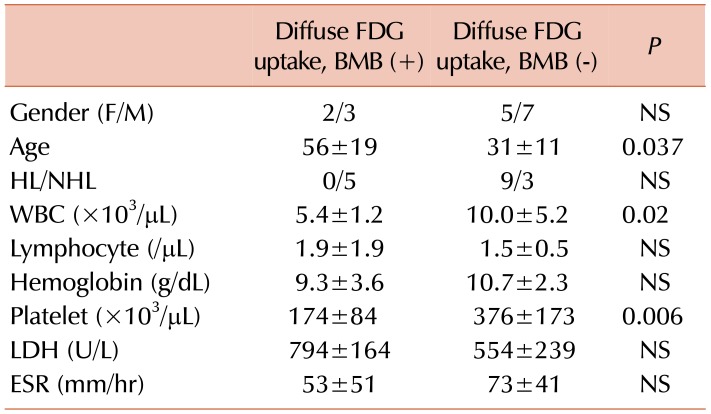

1415]. In our study, lymphoma cases showed diffuse BMI on PET/CT. This involvement may be due to BMI with lymphoma cells as well as anemia. However, cases with diffuse BMI on PET/CT were found to have similar Hb values when divided into groups with and without BMI on biopsy (

Table 5). This finding suggests that biopsy may produce a false negative for various reasons, although BMI was sometimes detected on PET/CT but not on biopsy. We did not find any significant difference in Hb levels between the biopsy-positive and -negative groups without PET/CT results, in our study (

Supplementary Table 2).

Focal BMI was detected on PET/CT in 4 cases, 2 (50%) of which were concordantly positive on biopsy. The rate of focal involvement on biopsy was 50%, which tended to be higher than in patients with diffuse involvement (29%). This finding suggests that diffuse involvement detected in PET/CT is often a false positive in our study patients (

Supplementary Table 4).

The Hb value tended to be lower in cases with DI compared to those with FI on PET/CT, but both were lower than normal range (

Supplementary Table 4). Similarly, low Hb levels were seen in true positive cases with DI compared to the biopsy-negative group (

Table 5). The lower Hb levels in the DI group may be due to increased diffuse bone marrow activity associated with anemia, lymphoma infiltration, or other causes of anemia. It is difficult to comment on patients with FI on PET/CT, because the number of patients was low (N=4), and there is little prior data on this topic in the literature.

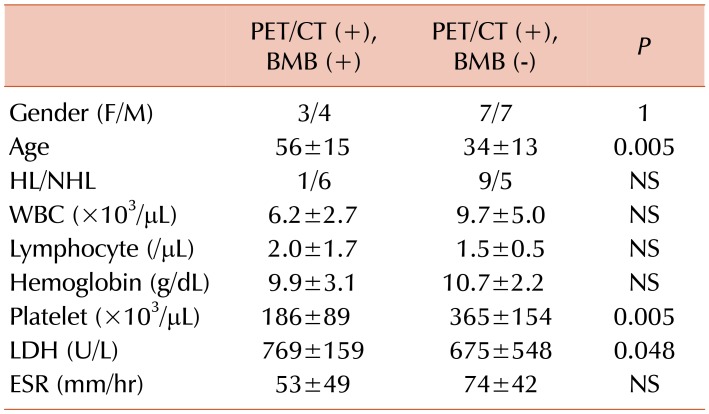

The cases with DI on PET/CT were divided into two groups as biopsy-positive and -negative. Age was significantly higher, and platelet counts were significantly lower in the biopsy-positive group (

Table 5). These findings remained consistent when the cases were divided according to biopsy results without considering PET/CT findings (

Supplementary Table 2). WBC counts were significantly lower in the group with DI and positive biopsy results. On the other hand, 7 (58%) out of 12 cases with DI on PET/CT and negative biopsy results had leukocytosis (

Table 5). Lower WBC count was not thought to be a clinically significant sign of lymphoma infiltration in the biopsy-positive group, as there was a significant difference in WBC counts in the biopsy-positive and -negative groups, but no leukopenia. However, a high WBC count was seen in most patients with DI and negative biopsy results which may be due to bone marrow reactivity. Murata et al. [

16] examined the relationship between hematological parameters and FDG uptake values in the bone marrow on PET/CT in 48 patients with solid tumors. They showed that the FDG uptake in bone marrow correlated with WBC and neutrophil counts but not RBC, lymphocyte, or platelet counts [

16]. However, this study did not examine BMI by biopsy, and it emphasized the short lifetime of neutrophils, suggesting that it may be associated with endogenous hematopoietic factors [

16]. In 24 cases with newly diagnosed HL, El-Galaly et al. [

17] found that patients with DI in bone marrow had higher WBC counts compared to patients with FI. They suggested that DI may be related to reactive bone marrow and not lymphoid infiltration [

17]. Twenty-three untreated lymphoma patients with DI in the bone marrow on PET/CT had lower Hb levels (91%), higher WBC counts (48%), and lower platelet counts (39%), higher platelet counts (22%) than the normal range [

18]. However, this study did not consider biopsy results and did not compare laboratory markers by biopsy results.

BMB is not a perfect gold standard and can result in false negatives because of the presence of patchy infiltration in bone marrow and removal of biopsy material from a non-involved site, or because of inadequate amount of biopsy tissue taken. However, in clinical use, BMB is routinely performed and accepted as a gold standard, as there have been no better alternatives. Pakos et al. [

19] investigated the role of PET/CT in assessing BMI in lymphoma in a meta-analysis. In this study, a total of 587 patients in 13 studies were examined, and detection of BMI on PET/CT showed a sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 95%, respectively [

1920]. We detected higher sensitivity and PPV but lower specificity and NPV compared to this previous work [

19]. However, the interpretation of our results may be influenced by the limitation that our study had a low number of patients and a mixed patient population (NHL and HL). In addition, the biopsy used as the gold standard was performed unilaterally and could have produced false negative results.

In our study, the concordance rate was higher than the discordance rate between PET/CT and BMB. In 50 HL and NHL cases, Carr et al. [

21] found a concordance rate of 78%. In our study, the rate of PET/CT (+) and biopsy (−) cases was high. This group of patients mostly had a diffuse uptake pattern on PET/CT and HL. In 24 cases with newly diagnosed HL, El-Galaly et al. [

17] found that none of them had BMI in biopsy. Myeloid hyperplasia in bone marrow causes DI on PET/CT, especially in HL cases, which may have caused the high number of these patients in our study [

17181921]. Among the PET/CT (+) patients, the true positive group was significantly older in age, and had lower platelet count and higher LDH levels, than the false positive group (

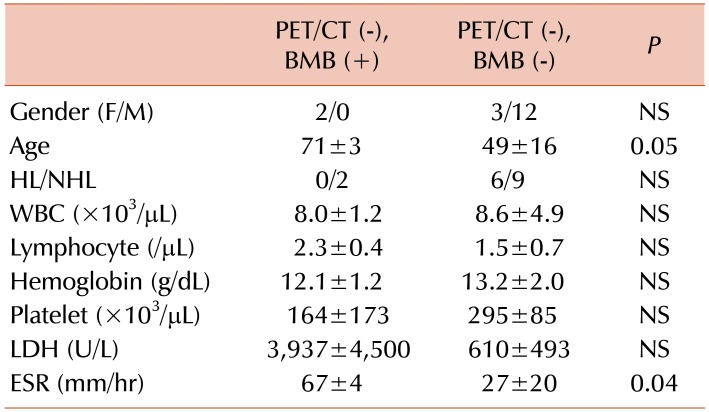

Table 4). These results suggest that hematologic markers could be used to risk-stratify patients with positive PET/CT for true BMI. Among PET/CT (−) patients, the false negative group had a higher ESR than the true negative group (

Table 5). These results suggest that patients with negative biopsy and PET/CT results are at very low risk for BMI.

Our findings suggest that patients with diffuse FDG uptake on PET/CT, advanced age and low platelet and WBC counts are likely to have BMI and could potentially forego BMB. Similarly, our findings also suggest that patients with negative PET/CT and no significant laboratory abnormalities, are very unlikely to have BMI.

Recent publications have shown that a PET/magnetic resonance imaging method is more successful in demonstrating diffuse BMI. This method is not widely available for current clinical use. At present, PET/magnetic resonance imaging has been mainly used in cases where PET/CT has failed [

2223]. Imaging techniques using advanced technology may progressively reduce the need of BMB for staging lymphoma.

This single-center retrospective cohort study describes the test characteristics of PET/CT for the appropriate identification of BMI in lymphoma patients. We also report several factors that could be used to help risk-stratify patients for true positive and true negative PET/CT results. Our findings should ideally be validated prospectively in a larger cohort. However, in conjunction with prior literature, it seems that PET/CT is a useful adjunct to BMB, in the diagnosis of BMI in lymphoma. PET/CT can also potentially be used to investigate BMI in patients who do not want to have BMB or who have conditions, such as obesity or severe osteoporosis, that make it technically difficult for performing BMB. Interpretation of BMB or FDG PET/CT alone may be insufficient to accurately diagnose BMI. Diagnostic strategies should incorporate both modalities, as well as clinical and laboratory findings.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download