Abstract

Recent studies suggest that the intracoronary administration of bone marrow (BM)-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) may improve left ventricular function in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). However, there is still argumentative for the safety and efficacy of MSCs in the AMI setting. We thus performed a randomized pilot study to investigate the safety and efficacy of MSCs in patients with AMI. Eighty patients with AMI after successful reperfusion therapy were randomly assigned and received an intracoronary administration of autologous BM-derived MSCs into the infarct related artery at 1 month. During follow-up period, 58 patients completed the trial. The primary endpoint was changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) at 6 month. We also evaluated treatment-related adverse events. The absolute improvement in the LVEF by SPECT at 6 month was greater in the BM-derived MSCs group than in the control group (5.9%±8.5% vs 1.6%±7.0%; P=0.037). There was no treatment-related toxicity during intracoronary administration of MSCs. No significant adverse cardiovascular events occurred during follow-up. In conclusion, the intracoronary infusion of human BM-derived MSCs at 1 month is tolerable and safe with modest improvement in LVEF at 6-month follow-up by SPECT.

Remarkable advances of early reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have contributed to a reduction of early mortality as well as complications of post-AMI (1-3). Nevertheless, delayed treatment leads to subsequent loss of cardiomyocyte and heart failure, which is a major cause of long term morbidity and mortality. In this respect, stem cell therapy has emerged as a novel alternative option for repairing the damaged myocardium (4).

The type and time of administration of stem cells are important issues. First, bone marrow (BM)-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are considered to be an attractive candidate because of high replicability, paracrine effect, ability to preserve potency, and no adverse reactions to allogeneic transplants (5, 6). However, the practical use of MSCs is limited because of time-consuming processes, expensive cost, need for strict control of infection and so on. Second, most studies were performed around 1 week after AMI with autologous bone marrow-derived progenitor cells (BMCs) (7-12). Although STAR-Heart study showed beneficial effects of BMCs in patients with chronic heart failure (13), there is little evidence of best time to treat AMI with stem cells (14). Assmus et al. demonstrated that the contamination of isolated BMCs with red blood cells reduced the function of BMCs and the recovery of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (15). However, purified MSCs can be expanded from BM and have no concern about contamination. Therefore, we hypothesized that treatment with purified BM-derived MSCs would be effective in patients with AMI despite of delayed administration. We designed a randomized, multicenter, pilot study to determine whether intracoronary infusion of autologous BM-derived MSCs at 1 month is safe and effective in patients with AMI.

From March 2007 to September 2010, total 80 patients were enrolled from three tertiary hospitals in Korea. Patients were eligible if 1) they were aged 18-70 yr; 2) they had ischemic chest pain for >30 min; 3) they were admitted to hospital <24 hr after the onset of chest pain; 4) electrocardiography (ECG) showed ST segment elevation >1 mm in two consecutive leads in the limb leads or >2 mm in the precordial leads; and 5) they could be enrolled in the study <72 hr after successful revascularization (defined as residual stenosis <30% of the infarct-related artery [IRA]).

We excluded patients with cardiogenic shock, life-threatening arrhythmia, advanced renal or hepatic dysfunction, history of previous coronary artery bypass graft, history of hematologic disease and malignancy, major bleeding requiring blood transfusion, stroke or transient ischemic attack in the previous 6 months, use of corticosteroids or antibiotics during the previous month, major surgical procedure in the previous 3 months, cardiopulmonary resuscitation for >10 min within the previous 2 weeks, positive skin test for penicillin, positive result for viral markers (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], hepatitis B virus [HBV], hepatitis C virus [HCV] and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] test), pregnant woman and possible candidate for pregnancy.

All patients were required to have successful revascularization of an IRA on coronary angiography at the time of randomization. All patients received aspirin (300 mg loading dose, then 100 mg daily) and clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose, then 75 mg daily) with optimal medical therapy according to the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (16-18), including aspirin, clopidogrel, beta blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (or angiotensin-receptor blocker) and statin unless these drugs were contraindicated. The use of aspiration thrombectomy or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was left to the investigator's discretion. If primary PCI was not available, a thrombolytic agent was used to reperfuse the occluded artery. We performed rescue PCI when ST-segment resolution was <50% at follow-up electrocardiography 90 min after thrombolytic therapy. Patients who were successfully reperfused with thrombolytic agents underwent elective PCI. Patients were randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to the MSCs group or control group. Control group received optimal medical therapy alone.

Twenty to twenty-five milliliters (mean±SD: 23.1±11.5 mL) of BM aspirates were obtained under local anesthesia from the posterior iliac crest in the MSCs group on 3.8±1.5 days after admission. All manufacturing and product testing procedures for the generation of clinical-grade autologous MSCs were carried out under good manufacturing practice (FCB-Pharmicell Company Limited, Seongnam, Korea). Mononuclear cells were separated from the BM by density gradient centrifugation (HISTOPAQUE-1077; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-low glucose (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin/100 µg/mL and streptomycin (Gibco). They were plated at 2-3×105 cells/cm2 into 75 cm2 flasks. Cultures were maintained at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 5-7 days, non-adherent cells were removed by replacing the medium; adherent cells were cultured for another 2-3 days. When the cultures were near confluence (70%-80%), adherent cells were detached by using trypsin containing ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA; Gibco) and replated at 4-5×103 cells/cm2 in 175 cm2 flasks. Cells were serially subcultured up to passage 4 or passage 5 for infusion (mean±SD: 4.4±0.5 passages).

On the day of administration, MSCs were harvested using trypsin and EDTA, washed twice with PBS and once with saline solution, and resuspended to a final concentration of 1×106 cells/kg. The criteria for the release of MSCs for clinical use included viability >80%, absence of microbial contamination (bacteria, fungus, virus, and mycoplasma) if undertaken 3-4 days before administration, and expression of CD73 and CD105 by >90% of cells and absence of CD14, CD34, and CD45 by <3% of cells as assessed by flow cytometry (data not shown). Also, the in vitro osteogenic and cardiomyogenic differentiation potential of MSCs in passage 0 or 1 was tested before release as a potency test. Alkaline phosphatase staining was used to demonstrate the osteogenic differentiation. Immunostaining with α-sarcomeric actin and troponin T was used to demonstrate the cardiomyogenic differentiation. Qualitative analysis showed well differentiation potential of all MSCs.

Injection of MSCs has been described elsewhere (11). The final preparation of MSCs (7.2±0.90×107 cells) contained into sterilized syringe was gently transferred and mixed to infusion syringe to minimize cell aggregation and then infused into the IRA via the central lumen of an over-the-wire balloon catheter (Maverick®, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). To allow the maximum contact time of MSCs with the microcirculation of the IRA, the balloon was inflated inside the stent at a low pressure to transiently interrupt antegrade blood flow during infusions. The entire cell injection was done during three transient occlusions, each lasting 2 to 3 min. Between occlusions, the coronary artery was reperfused for 3 min. After cell injection, repeated coronary angiography was undertaken to identify antegrade flow and the absence of other possible complications. Measurements of cardiac enzymes and electrocardiography were repeated to assess periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI). The mean duration of cultured MSCs from BM aspiration to intracoronary injection was 25.0±2.4 days.

Study visits were scheduled at 1, 2, and 6 months after hospital admission for the clinical and functional evaluation. Coronary angiography, electrocardiogram-gated single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and echocardiography were done at baseline and 6 months. Twenty-four hour ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitoring was done at baseline, 1 month and 6 months.

The primary endpoint of the study was absolute changes in global LVEF from baseline to 6 months after the MSCs administration measured by SPECT. Secondary endpoints were changes in left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), regional wall motion score index (WMSI) and major adverse cardiac events (MACE). MACE was defined as the composites of any cause of death, myocardial infarction, revascularization of the target vessel, re-hospitalization for heart failure, and life-threatening arrhythmia. MI was defined following the consensus statement of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction for clinical trials on coronary intervention (19). Hence, periprocedural MI was defined as the levels of cardiac biomarkers (troponin or creatine kinase-MB [CK-MB]) >3 times the 99th percentile of upper limit of normal (ULN) in patients with normal baseline levels, and as a subsequent elevation >3 times in CK-MB or troponin in patients with raised baseline levels. Target-vessel revascularization (TVR) included bypass surgery or repeat PCI of the target vessel(s).

SPECT was used for the non-invasive measurement of LVEF. A single dose of technetium-99m (99mTc)-sestamibi (Cardiolite® kit for the preparation of Technetium-99m Sestamibi for Injection; Dupont Merck Pharmaceutical Company, Billerica, MA, USA) was administered intravenously at rest, and data acquisition started 30-60 min later. SPECT data were acquired with a dual-headed gamma camera (Infinia H3000WT; GE Medical System, Tel Aviv, Israel) equipped with a low-energy, high-resolution collimator. Sixty-four images were obtained over a 180° orbit using 90° between the heads. Acquisitions were attenuation-corrected and gated for 16 frames/cardiac cycle. Total acquisition time was ~20 min. Vendor-specific, computer-enhanced edge detection methods were used to assess the LV epicardial and endocardial margins during the entire cardiac cycle. The computer calculated resting global LVEF from the gated SPECT images using an automated algorithm (20). The analysis of SPECT images was performed by blinded independent investigators at each participating center.

Regional and global LV function were measured by two-dimensional echocardiography according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography (21). LVEF was measured from the end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes calculated by the Simpson method from two orthogonal apical views. LV regional wall motion analyses were based on grading the contractility of individual segments. The left ventricle was divided into three levels (basal, mid, apical) and 16 segments. The basal and mid-levels were subdivided into six segments, and the apical level subdivided into four segments. Numerical scoring was adopted on the basis of the contractility of the individual segments. In this scoring system, higher scores indicated more severe abnormality in the motion of the wall: 1) normokinesis, 2) hypokinesis, 3) akinesis, 4) dyskinesis, and 5) aneurysm. The WMSI was derived by dividing the sum of wall motion score by the number of visualized segments; a normal WMSI was 1. Off-line assessment of all echocardiographic images was performed by one blinded independent investigator.

Sample size calculation is based on the result of BOOST trial (7). Study hypothesis is to demonstrate the superiority of MSCs treatment compared with control group. Type I and II error is set to 0.05 and 0.20 (statistical power 80%). The changes of LVEF and standard deviation are 6.7%±6.5% in BMCs group and 0.7%±8.1% in control group. Based on the assumption of 6% differences of LVEF and 1:1 allocation ratio with 27% drop-out rate, total 80 patients (40 patients in each group) are necessary.

Continuous variables are presented as mean±standard deviation. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons of continuous variables at baseline with those at follow-up were done with the paired t-test. Comparison of non-parametric data between groups was undertaken using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and the Mann-Whitney test. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows ver. 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

This study (SEED-MSC) was a randomized, open-label, multicenter phase-II/III clinical trial, which was approved by the Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) and registered with clinicaltrials.gov, number NCT01392105. The institutional review board of each participating center approved the treatment protocol before the initiation of enrollment. All patients provided written informed consent for inclusion in the trial.

Eighty patients were screened and 69 patients (86.3%) were included and randomly assigned to the MSCs group (n=33) or control group (n=36). After enrollment, 11 patients were excluded for the reasons listed in Fig. 1. The main cause of exclusion during follow-up was poor image quality. Two patients were excluded because of long-term medication of prohibited drug (corticosteroid).

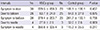

Table 1 illustrated that the two groups of patients were well matched. There were no differences with respect to cardiovascular risk factors and medical treatments. The Killip classification and angiographic characteristics including IRA were also similar between two groups.

Primary PCI was carried out in most cases, except 7 patients treated with thrombolytic agents (Table 2). Rescue PCI was done in 1 out of 7 patients because of reperfusion failure. There were no significant differences in procedural characteristics and time intervals from chest pain onset to treatment (Table 3).

Baseline LVEF was similar between the two groups (49.0%±11.7% in the MSCs group, and 52.3%±9.3% in the control group, P=0.247) (Table 4). The absolute change in global LVEF from baseline to 6 months was significantly improved in the MSCs group than the control group. (5.9%±8.5% vs 1.6%±7.0%, P=0.037) (Fig. 2). Baseline and 6 months LVEDV and LVESV showed no significant differences. The changes of LVEDV and LVESV also did not significantly different at 6-month follow-up in either group. There were no significant differences with regard to WMSI and change in WMSI.

Baseline LVEF was similar in the MSCs group and the control group (48.1%±8.0% and 51.0%±9.2%, respectively, P=0.215). Echocardiographic evaluation revealed a significant increase in LVEF from baseline to 6 months in the MSCs group but not in the control group (1.9%±2.7% and 0.5%±1.8%, P<0.001). Volumetric analyses of LV end-diastole and end-systole at baseline and 6 months and the changes at 6 months showed no significant differences between groups.

We analyzed the subgroup population treated <6 hr from symptom onset to first balloon inflation. Twenty-one patients of the stem cell group and 20 patients of the control group were analyzed. The improvement in LVEF was more significant in the MSCs group than in the control group according to SPECT (8.3%±8.3% and 1.3%±7.5%, P=0.007) and echocardiography (2.0%±2.8% and -0.3%±1.5%, P=0.003).

All procedures related to the BM aspiration and stem cell transplantation were well tolerated. There were no serious inflammatory reactions or bleeding complications at the site of iliac puncture after BM aspiration. Patients had no or mild angina during balloon inflation for infusion of MSCs. There were no serious procedural complications related to intracoronary administration of MSCs, such as ventricular arrhythmias, thrombus formation or dissection. Periprocedural MI was occurred in 2 patients. The peak levels of CK-MB and troponin I were 2.38 ng/mL (reference range <5 ng/mL) and 2.848 ng/mL (reference range <0.078 ng/mL) in one patient and 38.36 ng/mL and 5.304 ng/mL in the other. However, they had no symptoms and spontaneously recovered without additional treatment during 6-month follow-up.

There were no deaths, MI, TVR, stent thrombosis, life-threatening arrhythmia or stroke in both groups during 6-month follow-up. No significant arrhythmic events were recorded on 24 hr ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitoring. Paroxysmal non-sustained atrial fibrillation was found in 2 patients of the MSCs group (1 patient after PCI and 1 patient at 1 month follow-up) and in 1 patient of the control group after PCI.

In our study, the main finding is that the intracoronary administration of autologous purified BM-derived MSCs at 1 month after STEMI is tolerable without serious complications and provides modest improvement in LVEF at 6-month follow-up by SPECT.

The stem cell therapy for AMI increased LVEF by 2.99% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26%-4.72%, P=0.0007) in meta-analysis (4). In chronic ischemic heart failure, STAR-Heart study demonstrated that intracoronary BM cell therapy improved ventricular performance, quality-of-life and even survival (13). Our results met the primary endpoint of ≥4.3% improvement in LVEF compared with the control group. However, it is uncertain whether the relatively small increase in systolic function is meaningful in real-life situations (and not just a statistical difference).

In terms of safety, intracoronary administration of MSCs showed no serious adverse events, although periprocedural MI was developed in 2 patients. It seems to be a safe method to deliver stem cells via intracoronary route, since its introduction by Strauer et al. (22, 23). Moreover, ischemic pre-conditioning induced by transient balloon occlusion seems to be important to recruit MSCs into the infarcted myocardium (24, 25).

Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have shown the pleiotropic effects of MSCs such as antifibrotic, immunomodulatory, antiapototic and proangiogenic features as well as the impact of inflammation/cytokine expression on the different aspects of homing, including chemokine-chemokine receptor interactions, adhesion on endothelial cells, transendothelial migration, and invasion through the extracellular matrix (26). Stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1α is a major chemotactic paracrine factor for homing stem cells. SDF-1α-modified MSCs enhanced the tolerance of engrafted MSCs to hypoxic injury in vitro and improved their viability in a rat model of infarcted hearts, thus helping preserve the contractile function and attenuate LV remodeling (27). Moreover, MSC-conditioned medium directly inhibited the function of cardiac fibroblasts and resulted in a decrease of myocardial fibrosis with the consequent improvement of cardiac function by secreting antifibrotic factors such as adrenomedullin (28).

One of the main concerns is the time limitation for using autologous MSCs in acute setting. It is impossible to use autologous MSCs immediately because it takes time to harvest and culture cells for over 3 weeks. However, the optimal time for stem-cell therapy was not precisely identified. The temporal window of opportunity to maximize efficacy seems to be between the acute inflammatory response and scar formation. Several experimental studies and clinical subgroup analyses provided important clues that stem cell therapy might be effective within the first month after AMI, but not in very acute phase (24 hr after AMI) (29). Further clinical randomized trials need to confirm the optimal time to treatment.

The use of statin may ameliorate the microenvironment of injured myocardium and protect implanted MSCs. Animals treated with atorvastatin showed the improvement of myocardial perfusion and contractility compared with untreated animals by Yang et al. (30). The combined treatment of atorvastatin with MSCs reduced myocardial apoptosis, oxidative stress and expression of the inflammatory cytokines (30). Nearly 90% of our patients were prescribed statin at discharge. This synergic effect of statin might contribute to the functional recovery of damaged myocardium in our study.

The total ischemic time from symptom to treatment is the most important factor related to adverse outcomes. Mortality reduction was greatest in the first 2-3 hr after the onset of AMI, as a consequence of myocardial salvage (31). However, there was no mortality benefit by opening the occluded artery after 6 hr (31). Our subgroup analysis supports that BM-derived MSCs may help damaged myocardium to recover, if treated within 6 hr after AMI.

Our study has several limitations. First, our study enrolled relatively small number of patients. This limitation may attenuate the efficacy of intracoronary purified MSCs. Further large-scale randomized trials are needed. Second, there may be a technical problem for the assessment of LVEF. Although CMR was considered to be the "gold standard" for evaluation of LV function, it was impossible to use CMR at all institutions for the first time. We therefore measured LVEF with SPECT because we concluded that software-based automated analysis using SPECT could minimize inter-observer variability. Hovland et al. provided good evidence that SPECT showed the improvement of inter-observer agreement compared with echocardiography despite the possibility of an overestimation (32). Third, many patients were excluded from this study. Total patients of exclusion were 22/80 (27.5%). Ten of 40 (25%) in treatment group and 12/40 (30%) in control group were excluded. It was larger than we had anticipated. After randomization, 11 of 69 (15.9%) patients were excluded and the main cause was poor image quality. More patients in control group (5/36, 13.9%) were excluded than those in treatment group (1/33, 3.0%). However, there may be little possibility for selection bias, because radiologists were blinded to treatment information. The selection of inappropriate images was left at the discretion of radiologists. The final decision was confirmed by the agreement of investigators in each participating center. Fourth, we did not use diverse assessment tools such as the 6-min walking distance, exercise tolerance, pulmonary function test and quality of life. Finally, we did not evaluate the inter- and intra-observer variability in radiographic measurements. Sixth, there was no death in either group. Our study group showed a relatively preserved LV systolic function and low risk profiles. Long-term follow-up is needed to define the safety and beneficial effect of MSCs.

In conclusion, this pilot study was designed to identify the safety and practical efficacy of intracoronary purified autologous BM-derived MSCs in patients with STEMI. Intracoronary administration of autologous BM-derived MSCs at 1 month is tolerable and safe with modest improvement in LVEF at 6-month follow-up.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Impact of MSCs treatment on LVEF by SPECT. MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography. |

References

1. Gibson CM, Pride YB, Frederick PD, Pollack CV Jr, Canto JG, Tiefenbrunn AJ, Weaver WD, Lambrew CT, French WJ, Peterson ED, et al. Trends in reperfusion strategies, door-to-needle and door-to-balloon times, and in-hospital mortality among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction enrolled in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008; 156:1035–1044.

2. McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med. 2011; 124:40–47.

3. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, de Simone G, Ford ES, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011; 123:e18–e209.

4. Martin-Rendon E, Brunskill SJ, Hyde CJ, Stanworth SJ, Mathur A, Watt SM. Autologous bone marrow stem cells to treat acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2008; 29:1807–1818.

5. Parekkadan B, Milwid JM. Mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutics. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2010; 12:87–117.

6. Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, Dib N, Strumpf RK, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, DeMaria AN, Denktas AE, Gammon RS, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:2277–2286.

7. Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, Ringes-Lichtenberg S, Lippolt P, Breidenbach C, Fichtner S, Korte T, Hornig B, Messinger D, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2004; 364:141–148.

8. Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, Arnesen H, Abdelnoor M, Egeland T, Endresen K, Ilebekk A, Mangschau A, Fjeld JG, et al. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:1199–1209.

9. Schächinger V, Erbs S, Elsässer A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Hölschermann H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:1210–1221.

10. Meluzín J, Mayer J, Groch L, Janousek S, Hornácek I, Hlinomaz O, Kala P, Panovský R, Prásek J, Kamínek M, et al. Autologous transplantation of mononuclear bone marrow cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the effect of the dose of transplanted cells on myocardial function. Am Heart J. 2006; 152:975.e9–975.e15.

11. Janssens S, Dubois C, Bogaert J, Theunissen K, Deroose C, Desmet W, Kalantzi M, Herbots L, Sinnaeve P, Dens J, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006; 367:113–121.

12. Ge J, Li Y, Qian J, Shi J, Wang Q, Niu Y, Fan B, Liu X, Zhang S, Sun A, et al. Efficacy of emergent transcatheter transplantation of stem cells for treatment of acute myocardial infarction (TCT-STAMI). Heart. 2006; 92:1764–1767.

13. Strauer BE, Yousef M, Schannwell CM. The acute and long-term effects of intracoronary Stem cell Transplantation in 191 patients with chronic heARt failure: the STAR-heart study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010; 12:721–729.

14. Pereira MJ, Carvalho IF, Karp JM, Ferreira LS. Sensing the cardiac environment: exploiting cues for regeneration. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011; 4:616–630.

15. Assmus B, Tonn T, Seeger FH, Yoon CH, Leistner D, Klotsche J, Schächinger V, Seifried E, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Red blood cell contamination of the final cell product impairs the efficacy of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:1385–1394.

16. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1999 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44:671–719.

17. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Halasyamani LK, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, et al. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51:210–247.

18. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC Jr, King SB 3rd, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE Jr, et al. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:2205–2241.

19. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD. Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:2173–2195.

20. Germano G, Kiat H, Kavanagh PB, Moriel M, Mazzanti M, Su HT, Van Train KF, Berman DS. Automatic quantification of ejection fraction from gated myocardial perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Med. 1995; 36:2138–2147.

21. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005; 18:1440–1463.

22. Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, Köstering M, Hernandez A, Sorg RV, Kögler G, Wernet P. Repair of infarcted myocardium by autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation in humans. Circulation. 2002; 106:1913–1918.

23. Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, Gattermann N, Hernandez A, Sorg RV, Kögler G, Wernet P. Intracoronary, human autologous stem cell transplantation for myocardial regeneration following myocardial infarction. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2001; 126:932–938.

24. Lu G, Haider HK, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Sca-1+ stem cell survival and engraftment in the infarcted heart: dual role for preconditioning-induced connexin-43. Circulation. 2009; 119:2587–2596.

25. Kamota T, Li TS, Morikage N, Murakami M, Ohshima M, Kubo M, Kobayashi T, Mikamo A, Ikeda Y, Matsuzaki M, et al. Ischemic pre-conditioning enhances the mobilization and recruitment of bone marrow stem cells to protect against ischemia/reperfusion injury in the late phase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53:1814–1822.

26. Van Linthout S, Stamm Ch, Schultheiss HP, Tschöpe C. Mesenchymal stem cells and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: cardiac homing and beyond. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011; 2011:757154.

27. Tang J, Wang J, Guo L, Kong X, Yang J, Zheng F, Zhang L, Huang Y. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha improve cardiac remodeling via paracrine activation of hepatocyte growth factor in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Mol Cells. 2010; 29:9–19.

28. Li L, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Yu B, Xu Y, Guan Z. Paracrine action mediate the antifibrotic effect of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of global heart failure. Mol Biol Rep. 2009; 36:725–731.

29. Ter Horst KW. Stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction: are we missing time? Cardiology. 2010; 117:1–10.

30. Yang YJ, Qian HY, Huang J, Geng YJ, Gao RL, Dou KF, Yang GS, Li JJ, Shen R, He ZX, et al. Atorvastatin treatment improves survival and effects of implanted mesenchymal stem cells in post-infarct swine hearts. Eur Heart J. 2008; 29:1578–1590.

31. Gersh BJ, Stone GW, White HD, Holmes DR Jr. Pharmacological facilitation of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: is the slope of the curve the shape of the future? JAMA. 2005; 293:979–986.

32. Hovland A, Staub UH, Bjørnstad H, Prytz J, Sexton J, Støylen A, Vik-Mo H. Gated SPECT offers improved interobserver agreement compared with echocardiography. Clin Nucl Med. 2010; 35:927–930.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download