INTRODUCTION

Most countries around the world are interested in statistics related to births, but there is less interest in fetal death statistics. Additionally, comparison of fetal death rates is difficult due to differences in collecting systems of fetal death data among countries, and fetal mortality rates are underestimated due to missing fetal death data. However, fetal deaths are an important indicator of maternal, familial, social, and national health care (

1).

According to studies on fetal mortality, which have been ongoing internationally, fetal mortality rates have been reported to have decreased or remained unchanged. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines stillbirth as fetal death ≥ 28 completed weeks of gestational age or ≥ 1,000 g birth weight. The worldwide stillbirth rate has decreased by 14.5% from 22.1 stillbirths per 1,000 births in 1995 to 18.9 stillbirths per 1,000 births in 2009 (

2). The United States reports fetal mortality rates based on fetal deaths at 20 weeks of gestation or more, and fetal mortality rates in the United States have shown minor fluctuations from 2006 to 2013, but have remained almost unchanged (

3). In other studies, the stillbirth rate of high-income countries has remained almost unchanged over the past 20 years (

1).

Regarding stillbirths, there is a study reporting that obstetric conditions and placental abnormalities are the most common causes of stillbirths (

4). In another study, maternal overweight and obesity, advanced maternal age (> 35 years), smoking, abruption of placenta, pre-existing diabetes and hypertension, racial disparities, plurality, and being unmarried were reported as risk factors, and among them, maternal obesity, advanced maternal age, and smoking were reported as factors that, if improved, could prevent stillbirths (

56).

According to the WHO report, the perinatal mortality rate in developing countries is 5 times higher than in developed countries. There are 10 perinatal deaths per 1,000 fetal deaths and live births in developed regions, 50 in developing regions, and over 60 in the least developed countries (

1).

Most of the induced abortions, which account for a large proportion of fetal deaths, are known to occur within 12 weeks of gestation, and some have been reported to occur less than 25 weeks of gestation, but rarely thereafter (

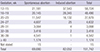

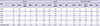

78). When looking at fetal death data in Japan, it was found that there are almost no induced abortions after 24 weeks of gestation (

9) (

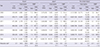

Table 1).

Table 1

Gestational age-specific fetal deaths by type of abortion in Japan, 2009–2014*

|

Gestation, wk |

Spontaneous abortion |

Induced abortion |

Total |

|

12–15 |

21,181 |

37,543 |

58,724 |

|

16–19 |

20,145 |

28,345 |

48,490 |

|

20–23 |

11,547 |

16,132 |

27,679 |

|

24–27 |

4,607 |

25 |

4,632 |

|

28–31 |

3,064 |

4 |

3,068 |

|

32–35 |

3,416 |

2 |

3,418 |

|

36–39 |

4,541 |

1 |

4,542 |

|

≥ 40 |

1,174 |

- |

1,174 |

|

Not stated |

15 |

- |

15 |

|

Total |

69,690 |

82,052 |

151,742 |

The birth rate in Korea has decreased when compared to other countries around the world, with an increasing number of elderly mothers and increased use of artificial insemination. This has resulted in increasing rates of multiple pregnancy and premature births, but the infant mortality rate and the neonatal mortality rate have decreased with the improvement of the level of neonatal medical care (

101112). Additionally, Han et al. (

13) reported that Korean perinatal mortality rate I has been continuously decreasing from 1996 to 2009. However, the fetal mortality rate is likely to increase because of the increase in maternal abdominal obesity, hypertension, and the prevalence of diabetes with increasing maternal age.

Since 2009, Statistics Korea has provided raw data on fetal deaths every year. However, there are few studies on fetal and perinatal mortality in Korea, both of which need to be studied. Consequently, the authors investigated the characteristics of fetal deaths and the changes in fetal deaths in Korea, by year, from 2009 to 2014, explored the effect of induced abortions by dividing the fetal deaths into 2 groups, before and after 24 weeks of gestation, and examined the yearly changes in perinatal mortality rates. These were also compared with the data from Japan and the United States to see the differences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and variables

This study was conducted to investigate fetal deaths and perinatal mortality rates by using the Annual Birth Data, the fetal and infant deaths data of the Complementary Cause of Death Data from Statistics Korea (

1415), the fetal and infant deaths data from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (

916), and the Period Linked Birth-Infant Death Data Files and Fetal Death Data Files from the United States National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) from 2009 to 2014 (

1718).

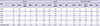

The fetal deaths data of Statistics Korea include fetal deaths, which were registered at a gestational age over 16 weeks, including both induced and spontaneous abortions. The NCHS data in the United States include all gestational ages, but exclude induced abortions. We compared the data of the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare with that of Korea and that of the United States, because induced abortions are excluded in the data of the United States, which is a limiting factor in directly comparing fetal deaths between Korea and the United States. The data from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare include fetal deaths at gestational ages 12 weeks or more, both induced and spontaneous abortions, and distinguish between the 2 types of abortion. In this study, fetal deaths at 20 weeks of gestation or more were selected for the targets in consideration of the United States fetal deaths criteria and perinatal death II (

Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1

Selection of study populations for the study.

*Data from the Statistics Korea ( 1415); †Data from Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare ( 916);

‡Data from the United States National Center for Health Statistics ( 1718).

|

Among the fetal deaths between 2009 and 2014, 23,602 fetal deaths in Korea, 44,513 in Japan, and 144,248 in the United States occurred at gestational ages 20 weeks or more. Gestational age and birth weight of newborns were not limited in each country, and the perinatal mortality rate was investigated using that data. The fetal mortality rate, the fetal mortality rate per gestation, the male and female ratio of fetal deaths, the number of fetal deaths, and the yearly trends of fetal mortality rate were confirmed. Additionally, fetal deaths were divided into the early fetal deaths before 24 weeks of gestation, which are thought to include induced abortions, and the late fetal deaths, after 24 weeks of gestation, which are comprised of mostly spontaneous abortions, and investigated the differences in the yearly fetal mortality rates.

The annual fetal mortality rate was calculated as the number of fetal deaths per 1,000 fetal deaths and live births per year. The fetal mortality rate per gestation was calculated with the number of fetal deaths at a specified gestational age per 1,000 fetal deaths and number of live births at a specified gestational age.

Among fetal deaths, the proportions of plurality, congenital anomalies, and elderly mothers over 35 years of age, among the total mothers of fetal death cases, were examined, and, due to the lack of Japanese data on this, gestation was restricted to fetal deaths at more than 22 weeks. In the United States, the data on congenital anomalies among fetal death cases were partially provided, and the total number of congenital anomalies was not identified.

This study analyzed the age distribution of mothers of fetal death cases, and the yearly trends of maternal age specific fetal mortality rate in Korea. Perinatal mortality rates were compared by country and year. The perinatal mortality rates comprise the perinatal mortality rate I, used by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the perinatal mortality rate II, used by the WHO and the United Nations. The perinatal mortality rate I refers to neonatal deaths within 7 days and fetal deaths at 28 weeks of gestation or more per 1,000 live births plus fetal deaths for their respective time period, and the perinatal mortality rate II refers to neonatal deaths within 7 days and fetal deaths at 22 weeks of gestation or more per 1,000 live births plus fetal deaths for their respective time period. In addition, the perinatal definition I of Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the same as the perinatal mortality rate I mentioned above, but the perinatal definition II of CDC is the most inclusive definition, and includes infant deaths within 28 days and fetal deaths at 20 weeks of gestation or more per 1,000 live births plus fetal deaths for their respective time period. There were 5,690 fetal deaths over 28 weeks of gestation in Korea, 12,202 in Japan, and 70,900 in the United States; there were 15,560 fetal deaths at 22 weeks of gestation or more in Korea, 20,265 in Japan, and 116,789 in the United States. There were 3,183 early neonatal deaths within 7 days of birth in Korea, 4,829 in Japan, and 77,311 in the United States (

Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). Categorical variables were analyzed by the χ2 test. Differences in continuous variables were assessed by Student's t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konyang University Hospital (IRB No. 2017-02-001). Since all of the data we used were public-use data files, informed consents were exempted by the board.

RESULTS

Characteristics of fetal deaths (≥ 20 weeks gestation) in Korea, Japan, and the United States, 2009–2014

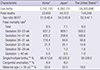

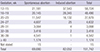

From 2009 to 2014, the total number of births was 2,742,725 infants in Korea, 6,262,731 infants in Japan, and 24,005,896 infants in the United States, and the numbers of fetal deaths at 20 weeks of gestation or more were 23,602 in Korea, 44,513 in Japan, and 144,248 in the United States. The total fetal mortality rate was 8.5 per 1,000 fetal deaths and live births in Korea, 7.1 in Japan, and 6.0 in the United States. The ratio of male to female rates of fetal deaths was 1.07 in Korea, 1.18 in Japan, and 1.12 in the United States, demonstrating that the proportion of males among fetal deaths was highest in Japan.

The gestational age specific fetal mortality rates of the 3 countries were compared. The gestational age specific fetal mortality rate in Korea was the highest, at 937.3 fetuses in the 20–23 weeks gestational age group, and the fetal mortality rate decreased sharply as gestation increased. In Japan, the highest fetal mortality rate was 909.1 in the 20–23 weeks gestational age group and then rapidly decreased. In the United States, exclusive of induced abortion, the fetal mortality rate was as high as 509.2 in the 20–23 weeks gestational age group and then rapidly decreased. Gestational age over 36 weeks in the United States showed a slightly higher fetal mortality rate than in Korea and Japan.

There were similar rates of congenital anomalies in fetal death cases over 22 weeks in Korea and Japan, 8.9% and 8.0%, respectively. Among mothers of fetal death cases over 22 weeks of gestation, the percentage of maternal age of 35 years or older was 23.6% in Korea, 32.2% in Japan, and 18.6% in the United States (

Table 2).

Table 2

Number of live births and demographic characteristics of fetal deaths (≥ 20 weeks) in Korea, Japan, and the United States, 2009–2014

|

Characteristic |

Korea*

|

Japan†

|

The United States‡,§

|

|

Live births |

2,742,725 |

6,262,731 |

24,005,896 |

|

Fetal deaths |

23,602 |

44,513 |

144,248 |

|

Sex ratio (M:F)∥

|

51.6:48.4 |

54.2:45.8 |

52.9:47.1 |

|

Fetal mortality rate¶

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

8.5 |

7.1 |

6.0 |

|

Gestation 20–23 wk |

937.3 |

909.1 |

509.2 |

|

Gestation 24–27 wk |

433.2 |

258.6 |

168.6 |

|

Gestation 28–31 wk |

118.4 |

94.6 |

58.8 |

|

Gestation 32–35 wk |

21.5 |

25.1 |

14.8 |

|

Gestation 36–39 wk |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

|

Gestation ≥ 40 wk |

0.5 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

|

Single/multiple births,** % |

89.4/10.6 |

92.0/8.0 |

92.0/8.0 |

|

Congenital anomalies,** % |

8.9 |

8.0 |

- |

|

Maternal age (≥ 35 yr),** % |

23.6 |

32.2 |

18.6 |

Fetal deaths (≥ 20 weeks gestation) with demographic, medical, and health characteristics in Korea, 2009–2014

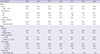

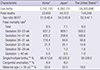

In the period 2009–2014, mean maternal age and rates of mothers of fetal death cases who were aged 35 and over in Korea, increased steadily. In addition, rates for receiving prenatal care increased from 53.9% in 2009 to 75.0% in 2014, and rates for cesarean section increased from 14.8% in 2009 to 21.6% in 2014.

Rates of multiple births showed increasing trends, but premature birth rate and low birth weight rate showed slightly decreasing trends. There were slightly more males than females, but there were no significant differences by year (

Table 3).

Table 3

Demographic characteristics of fetal deaths (≥ 20 weeks) in Korea, 2009–2014

|

Characteristics*

|

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

Total |

|

Mother |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age, yr |

29.3 |

30.2 |

30.7 |

30.9 |

31.2 |

31.4 |

30.5 |

|

Aged ≥ 35 yr |

21.2 |

24.3 |

25.9 |

24.3 |

26.1 |

27.4 |

24.6 |

|

Prenatal care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

53.9 |

60.8 |

65.5 |

66.5 |

72.2 |

75.0 |

64.7 |

|

No |

25.5 |

20.8 |

19.9 |

12.7 |

9.6 |

7.4 |

16.8 |

|

Unknown |

20.6 |

18.4 |

14.6 |

20.8 |

18.2 |

17.6 |

18.5 |

|

Delivery methods |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NSVD |

85.3 |

84.0 |

82.4 |

80.4 |

79.0 |

78.4 |

81.8 |

|

Cesarean section |

14.8 |

16.0 |

17.6 |

19.6 |

21.0 |

21.6 |

18.2 |

|

Fetus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plurality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Single |

91.9 |

90.7 |

89.9 |

88.6 |

89.2 |

88.6 |

89.9 |

|

Multiple births |

8.1 |

9.4 |

10.1 |

11.4 |

10.8 |

11.4 |

10.1 |

|

Period of gestation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

> 32 wk |

87.0 |

85.1 |

83.1 |

82.5 |

81.7 |

82.1 |

83.8 |

|

Preterm (> 37 wk) |

93.6 |

93.1 |

91.8 |

91.2 |

91.7 |

91.6 |

92.3 |

|

Birth weight |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

> 1,500 g |

82.8 |

83.0 |

80.8 |

80.3 |

79.9 |

81.8 |

81.5 |

|

> 2,500 g |

91.4 |

91.4 |

90.3 |

89.7 |

89.6 |

90.6 |

90.6 |

|

≥ 4,000 g |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

|

Sex of fetus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male-female ratio |

1.01 |

1.02 |

1.07 |

1.03 |

1.00 |

1.06 |

1.03 |

Fetal mortality rates (≥ 20 weeks gestation), by period of gestation: Korea, Japan, and the United States, 2009–2014

By 2009–2014, while the number of births in Korea decreased by 2.1%, the number of fetal deaths showed a sharp reduction rate of 34.5%, and there was a reduction by 11.5% in Japan and 3.2% in the United States.

Korea's fetal mortality rate declined by 32.9% from 11.0 fetal deaths per 1,000 fetal deaths and live births, in 2009, to 7.4 in 2014, the largest decline among the 3 countries. The fetal mortality rate in Japan decreased from 7.3 in 2009 to 6.9 in 2014, a decline of 5.6%, and there was no difference in the fetal mortality rate in the United States, which was 5.9, both in 2009 and in 2014. The fetal mortality rate in 2014 was lowest in the United States (5.9), followed by Japan (6.9), and Korea (7.4), but the difference between countries was smaller than in 2009. The fetal mortality rates were divided into early (before 24 weeks of gestation), and late (at or after 24 weeks of gestation) to investigate the transitional aspects of fetal deaths. The fetal mortality rate in the early period in Korea decreased from 968.9 fetal deaths in 2009 to 910.5 fetal deaths in 2014, a decline of 6.0%, and the fetal mortality rate in the late period decreased by 25.9%, from 4.6 in 2009 to 3.4 in 2014. In Japan, the fetal mortality rate in the early period decreased by 0.5%, from 912.5 in 2009 to 907.9 in 2014, and the fetal mortality rate in the late period decreased by 11.6% from 2.8 in 2009 to 2.5 in 2014. In the United States, the early and late fetal mortality rates increased slightly, but there was no significant difference. In the comparison between countries, both the early and late fetal mortality rates showed the greatest decrease in Korea (

Table 4).

Table 4

Fetal mortality rates (≥ 20 weeks) by period of gestation in Korea, Japan, and the United States, 2009–2014

|

Year |

Korea*

|

Japan†

|

The United States‡

|

|

Live births |

Fetal deaths |

FMR§

|

Live births |

Fetal deaths |

FMR§

|

Live births |

Fetal deaths |

FMR§

|

|

Total |

Early |

Total |

Early |

Total |

Early |

Total |

Early |

Total |

Early |

Total |

Early |

|

Late |

Late |

Late |

Late |

Late |

Late |

|

2009 |

444,849 |

4,964 |

2,927 |

11.0 |

968.9 |

1,070,035 |

7,843 |

4,829 |

7.3 |

912.5 |

4,137,836 |

24,714 |

8,505 |

5.9 |

502.7 |

|

2,037 |

4.6 |

3,014 |

2.8 |

16,209 |

3.9 |

|

2010 |

470,171 |

4,320 |

2,585 |

9.1 |

947.2 |

1,071,304 |

7,707 |

4,663 |

7.1 |

912.7 |

4,007,105 |

24,071 |

8,389 |

6.0 |

512.5 |

|

1,735 |

3.7 |

3,044 |

2.8 |

15,682 |

3.9 |

|

2011 |

471,265 |

3,778 |

2,171 |

8.0 |

933.4 |

1,050,806 |

7,611 |

4,692 |

7.2 |

906.5 |

3,961,220 |

24,144 |

8,299 |

6.1 |

515.9 |

|

1,607 |

3.4 |

2,919 |

2.8 |

15,845 |

4.0 |

|

2012 |

484,550 |

3,781 |

2,126 |

7.7 |

927.2 |

1,307,231 |

7,281 |

4,503 |

7.0 |

903.9 |

3,960,796 |

23,921 |

8,202 |

6.0 |

510.2 |

|

1,655 |

3.4 |

2,778 |

2.7 |

15,719 |

4.0 |

|

2013 |

436,455 |

3,509 |

1,954 |

8.0 |

919.1 |

1,029,816 |

7,127 |

4,547 |

6.9 |

910.7 |

3,940,764 |

23,487 |

7,961 |

5.9 |

507.6 |

|

1,555 |

3.6 |

2,580 |

2.5 |

15,526 |

3.9 |

|

2014 |

435,435 |

3,250 |

1,770 |

7.4 |

910.5 |

1,003,539 |

6,944 |

4,445 |

6.9 |

907.9 |

3,998,175 |

23,911 |

8,017 |

5.9 |

506.2 |

|

1,480 |

3.4 |

2,499 |

2.5 |

15,894 |

4.0 |

|

Total |

2,742,725 |

23,602 |

13,533 |

8.5 |

937.3 |

6,262,731 |

44,513 |

27,679 |

7.1 |

909.1 |

24,005,896 |

144,248 |

49,373 |

6.0 |

509.2 |

|

10,069 |

3.7 |

16,834 |

2.7 |

94,875 |

4.0 |

|

Reduction rate∥

|

2.1 |

34.5 |

39.5 |

32.9 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

11.5 |

8.0 |

5.6 |

0.5 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

5.7 |

−0.1 |

−0.7 |

|

27.3 |

25.9 |

17.1 |

11.6 |

1.9 |

−1.4 |

Fetal mortality rate, by age of mother in Korea, 2009–2014

The maternal age of fetal death cases in Korea were identified. The proportion of mothers 30–34 years old among the total mothers of fetal death cases was the highest, and the proportion of mothers older than 30 years of age increased from 52.3% in 2009 to 67.7% in 2014. The proportion of mothers younger than 30 years old decreased from 47.3% in 2009 to 29.6% in 2014. The proportion of elderly mothers over 35 years of age among mothers of fetal death cases yearly increased from 21.2% in 2009 to 26.6% in 2014.

The mean fetal mortality rate by maternal age was compared. Fetal mortality rates for the group of 12–19 year olds and the group of 40–55 year olds were higher, with 84.1 and 20.7 fetal deaths, respectively. The fetal mortality rates of most maternal age groups showed a decreasing trend by year. In 2009, the fetal mortality rates of the maternal age groups of 12–19 year olds, and over 40 years of age were 147.2 fetal deaths and 31.6 fetal deaths per 1,000 births and fetal deaths, and decreased to 51.7 and 16.3 respectively in 2014 (

Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2

Trends of fetal mortality rate by maternal age in Korea, 2009–2014*

Fetal mortality rate was higher in the 12–19 years old and the 40–90 years old mother group than in the others, the 25–29 years old mother group showed the lowest rate. The fetal mortality rate of all decreased by year.

*Data from Statistics Korea ( 1415).

|

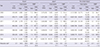

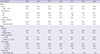

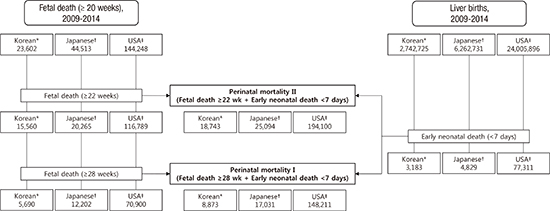

Perinatal mortality rates I and II: Korea, Japan, and the United States, 2009–2014

Perinatal mortality rates I and II were lowest in Japan, followed by Korea and the United States. The yearly trends of the perinatal mortality rate I, showed that it was 2.9 in Japan, 3.5 in Korea, and 6.2 in the United States in 2009, and 2.5 in Japan, 3.1 in Korea, and 6.2 in the United States in 2014, showing a decrease of 13.8% in Japan and 9.8% in Korea, but there was little difference in the United States. For perinatal mortality rate II, Korea showed a decreased rate of 29.0% from 8.5 in 2009 to 6.0 in 2014, and Japan decreased by 11.5% from 4.2 in 2009 to 3.7 in 2014, demonstrating that the decreased rate in Korea was greater than that in Japan. In the United States, perinatal mortality rate II did not show a significant change (

Table 5).

Table 5

Perinatal, neonatal, and infant mortality rates in Korea, Japan, and the United States, 2009–2014

|

Year |

Korea*

|

Japan†

|

The United States‡

|

|

PMR I§

|

PMR II∥

|

Early NMR¶

|

NMR**

|

IMR††

|

PMR I§

|

PMR II∥

|

Early NMR¶

|

NMR**

|

IMR††

|

PMR I§

|

PMR II∥

|

Early NMR¶

|

NMR**

|

IMR††

|

|

2009 |

3.5 |

8.5 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

3.2 |

2.9 |

4.2 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

6.2 |

8.1 |

3.3 |

4.1 |

6.3 |

|

2010 |

3.3 |

7.1 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

3.2 |

2.9 |

4.2 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

2.3 |

6.1 |

8.0 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

6.1 |

|

2011 |

3.1 |

6.4 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

4.1 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

2.3 |

6.2 |

8.1 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

|

2012 |

3.1 |

6.3 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

4.0 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

2.2 |

6.2 |

8.1 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

5.9 |

|

2013 |

3.3 |

6.5 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

3.0 |

2.6 |

3.7 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

2.1 |

6.2 |

8.0 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

5.9 |

|

2014 |

3.1 |

6.0 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

3.7 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

2.1 |

6.2 |

8.0 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

5.8 |

|

Total |

3.2 |

6.8 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

4.0 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

2.2 |

6.2 |

8.1 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

|

Reduction rate‡‡

|

9.8 |

29.0 |

8.2 |

1.0 |

5.8 |

13.8 |

11.5 |

13.3 |

19.1 |

13.2 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

2.1 |

4.0 |

7.5 |

DISCUSSION

In Korea, the number of newborns decreased by 2.1% from 444,849 persons in 2009 to 435,435 persons in 2014, but births of premature infants less than 37 weeks increased by 15% from 25,374 persons to 29,086 persons. And we identified that the number of fetal deaths and the fetal mortality rate in Korea decreased more than 30% in the last 6 years. This shows that fetal deaths are not simply reduced in proportion to the decline in fertility rates. Furthermore, the rate of reduction of fetal mortality rate was more than 25%, even at 24 weeks of gestation or more, which is expected to have little effect by induced abortion. Additionally, fetal mortality rate of 16–19 weeks of gestation group has continuously declined since 2009 to 2014, which is not included in the result of this study.

And premature birth rate and low birth weight rate of fetal deaths showed slightly decreasing trends, despite the increase in the proportion of fetal deaths with multiple fetuses due to the increase in older mothers. Rates for cesarean sections also increased and notably, rates for receiving prenatal care increased from 53.9% in 2009 to 75.0% in 2014. According to the previous study, Korean perinatal mortality rate I has been continuously decreasing from 1996 to 2009, which indicates that it is related to the development of obstetric and neonatal medical care (

13).

Significant reductions in fetal mortality rate and perinatal mortality rate I and II from 2009 to 2014 were showed in our study, which also seem to be relevant to the result of further development of perinatal medical care. Such as, high-risk mothers are expected to receive adequate prenatal care and deliver at an appropriate time, which will contribute to reduce the fetal deaths, and secondarily will affect the increase in preterm delivery. According to the data of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, due to adequate prenatal care, the number of mothers who were diagnosed and treated for cervical incompetence and other abnormalities of the cervix increased steadily from 4,320 persons in 2010 to 5,946 persons in 2016 (

19). And the number of maternal deaths decreased from 60 persons in 2009 to 38 persons in 2015 (

14).

In addition, national medical support programs for high-risk mothers and newborn babies may have played a partial role in reducing fetal deaths. Since 2008, Korea has implemented maternity and childcare subsidies to all pregnant women to receive prenatal care more regularly than before, so that mothers and fetuses can be maintained in good health, and early detection of disease can help guide appropriate treatment. Recent reports have shown that this has helped pregnant women receive adequate antenatal care (

20).

Additionally, it has been reported that since 2011, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea has continued to establish obstetrics clinics in vulnerable areas, improving pregnant women's access to medical facilities, resulting in fewer major complications for pregnant women living in vulnerable areas, and increasing healthy pregnancies and safe childbirth (

21).

Third, since 2008, with ongoing support for the installation and operation of the Regional Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), which extends NICU facilities, equipment, and medical personnel by 2015, 46 NICU and 380 NICU beds have increased, and the accompanying newborn mortality rate and infant mortality rate is expected to decrease, which will result in a qualitative improvement in prematurity survival rate (

22).

Lastly, since 2014, the project has been expected to contribute to improving the level of perinatal care through implementing a high-risk integrated maternal and neonatal care center support project, and the Korean Neonatal Network is supposed to improve the quality of very low birth weight infants care, and to play a major role in reducing the variation in the level of high risk infants care between regions (

2324).

The fetal mortality rate was significantly different according to the maternal age; the fetal mortality rate by the maternal age was the highest in the 12–19 year olds group, followed by those over 40 years old. However, when the fetal mortality rate by the maternal age was compared by year, it decreased in all age groups. The proportion of elderly mothers increased in all 3 countries, but the fetal mortality rate showed a tendency to decrease.

The fetal mortality rates at 20–23 weeks of gestation were significantly higher in Korea and Japan, with 937 fetal deaths and 909 fetal deaths, respectively, per 1,000 births and fetal deaths, than the 509 fetal deaths in the United States. The lowest fetal mortality rate in the United States at 20–23 weeks of gestation was partially due to the exclusion of induced abortions in the fetal deaths data, racial disparities and the high level of perinatal care. And the birth rate of 20–23 weeks of gestation among all births was 0.2% in the United States, 0.03% in Korea, and 0.04% in Japan, respectively, demonstrating that it is likely that a much higher birth rate at 20–23 weeks of gestation in the United States than other countries may have affected the fetal mortality rate at this period. Even if the survival probability is very low in the United States, it is estimated that more cases are classified as live births, rather than as fetal deaths, if they live immediately after birth.

The fetal mortality rate in the early fetal deaths before 24 weeks of gestation, which are thought to include induced abortions, decreased from 968.9 fetal deaths in 2009 to 910.5 fetal deaths in 2014, a decline of 6.0% in Korea. And, from the results of the survey on induced abortions in 2010, the rates of induced abortions in 2005, 2008, 2009, and 2010 were 29.8, 21.9, 17.2, and 15.8, respectively, indicating a steady decline in Korea (

8).

This study has the following limitations. First, as Korean data do not distinguish between spontaneous abortion and induced abortion, it was difficult to investigate the exact induced abortion rate. Second, the United States data did not include induced abortion, making it difficult to compare the 3 countries directly. Third, the difference in fetal mortality rates among countries may be due to differences in prenatal care rates or differences in the data collection system on fetal deaths, which was difficult to adjust in this study. Fourth, although the above-mentioned development of medical level and various national medical support projects have been examined as possible causes of the decrease of fetal deaths, it is unknown how much of a contribution this actually is. Despite these limitations, this study was conducted to investigate the trends of the characteristics of fetal deaths over 20 weeks of gestation, fetal mortality rate, and perinatal mortality rate in Korea, and is meaningful in that it can assess the present state of Korean fetal deaths by comparing with the fetal deaths in United States and Japan.

In conclusion, by 2009–2014, the number of fetal deaths and the fetal mortality rate in Korea showed the greatest rate of decline, compared to Japan and the United States, and also showed the greatest rate of decline when divided into cases before and after 24 weeks of gestation. Both perinatal mortality rates I and II tended to decrease, and perinatal mortality rate II decreased the most. In this study, we identified that the indices of fetal deaths in Korea are improving rapidly. In order to maintain this trends, improvement of perinatal care level and stronger national medical support policies should be maintained continuously.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download