INTRODUCTION

According to the Korean ‘Multicultural Family Support Act’ 2012, the definitions of multi-cultural family (MCF) are: 1) marriage-based immigrants under the Basic Act on the Treatment of Foreigners, 2) men acquiring Korean nationality after marriage according to the Nationality Act, and 3) all members getting Korean nationality for other reasons. Marriage-based immigrants are persons acquiring naturalization as members of MCF, according to the Basic Act on the Treatment of Foreigners in Korea or the Nationality Act (

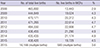

1). Based on these definitions, the number of MCF individuals is the sum of marriage-based immigrants, men getting Korean nationality after marriage, and all members getting Korean nationality for other reasons. The members of MCF family include an MCF member, spouse, and their children (

Table 1).

Table 1

Definition of MCF according to the Korean Multicultural Family Support Act (2012)

|

Term |

Definition |

|

The No. of MCFs |

Marriage based immigrants AND |

|

Men getting Korean nationality after marriage according to the Nationality Act AND |

|

All members getting Korean nationality for other reasons |

|

The No. of people in MCFs |

One's own self of MCF |

|

Spouse AND |

|

Children AND |

|

Other family members |

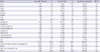

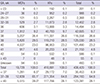

The number of MCFs in Korea has increased rapidly after 2002. The major increase is from marriage-based immigrants, due to the inability of a high number of single male farmers and low-income men in the city in procuring a spouse. The numbers have increased over a period of time: 142,015 in 2007, 221,548 in 2010, 281,295 in 2013, and 294,663 in 2015 (

2). The numbers of all members of MCF have increased from 328,000 in 2007, 564,000 in 2010, 754,000 in 2013, to 889,000 in 2015 (marriage-based immigrants and men acquiring Korean nationality after marriage, 295,000; children under 8 years old, 198,000; other family members including spouse, 396,000). The number is expected to increase further and the total number of MCFs is expected to increase to a million (

23). Hence, a social policy for their management is necessary.

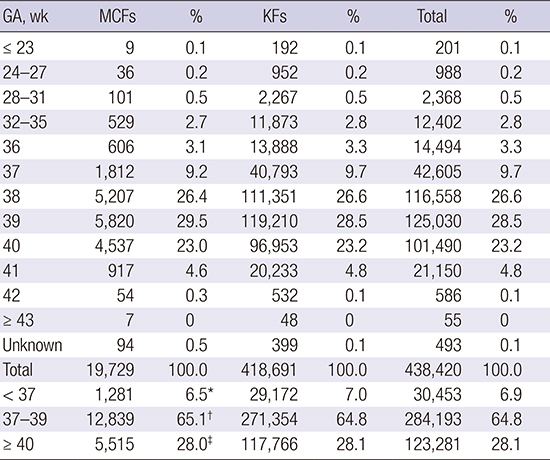

The number of marriages in MCF and the percentage in the total number of marriages in Korea has shown a decline: 36,629 (11.2%) in 2008, 29,224 (8.9%) in 2012, 22,462 (7.4%) in 2015. The number of births in MCF increased from 13,443 in 2008 to 20,312 in 2010, and hit a new high of 22,908 in 2012. However, it declined to 21,174 in 2014 and 19,729 in 2015. MCF births contribute significantly to the total number of births in Korea: 2.9% in 2008, 4.3% in 2010, 4.9% in 2014, 4.5% in 2015. The numbers of MCF births are about 1/20th of the total births in Korea (

4).

It was in 2006 that Korea initiated setting up and implementing MCF support policies. The Multicultural Family Support Act was enacted in 2008 and amended in 2012 (

1). Since marriage-based immigrants (25,623 males and 119,649 females in 2015) and married naturalized person (10,308 males and 82,941 females in 2015) in MCF are mostly females (

2), the socio-economic and medical support system currently in operation, was included under the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family from 2010. The first MCF support policy was rolled out from 2010 to 2012 (

5), and the second MCF supporting policy for 2013 to 2017 (

6) from the ministry of Gender Equality and Family is currently operational.

This study is a statistical analysis of MCF birth factors in 2015. It surveyed MCF births' data from Statistics Korea. Of the total numbers of births in 2015, the number of MCF births was 19,729 (4.5%) and the number of births in Korean families (non-MCFs or KFs) was 418,691 (95.5%) (

7).

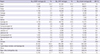

The objective of this study is to determine the number and frequency of MCF births in Korea, and to compare the birth distribution by regional groups. We hypothesized that there is a higher number of adverse outcomes in MCF births compared to KF births. We compared the 2 groups with respect to birth weight (BW), gestational age (GA), birth order, place of delivery, cohabitation period before birth of the first child, and parental education level. Besides, the objective of this study was to provide the statistical data of MCF births in 2015, which will help in planning MCF obstetric and neonatal medical care in Korea for the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We extracted the data of MCF births in 2015 from Statistics Korea, and the number of KF births was considered as total births excluding MCF (

78). Of the total number of births in 2015 (438,420), the number of MCF births was 19,720 (4.5%) and the number of non-MCF (KF) births was 418,691 (95.5%). The research subjects are the people in the MCF births group and the control group includes the people in the KF births group.

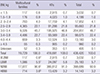

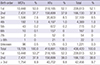

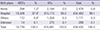

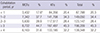

We ascertained the percentage of MCF births per year from 2008 to 2015. The statistical data of birth between 2 groups (MCF vs. KF) were compared with respect to the geography, number of marriages by region, BW (very low BW infant [VLBWI] with BW < 1.5 kg; low BW infant [LBWI] with BW < 2.5 kg; normal BW infant [NBWI] with BW 2.5–3.9 kg; high BW infant [HBWI] with BW ≥ 4.0 kg), GA, birth order, place of delivery, cohabitation period of parents before the first child, and parental education level. We analyzed if the MCF group has higher adverse outcomes compared to the KF group.

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was used to compare the proportions of adverse birth outcomes between MCF and KF. All analyses were performed using STATA software version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), P values of < 0.050 were considered statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

In the early 1990s, international marriages accounted for only 1% of total marriages in the Korean society. Since the mid-1990s, the number of international marriages increased and marriages of MCFs accounted for more than 10% of the total marriages since the mid-2000s. In 2006, ‘the social integration support plan for the female marriage immigrants’ family and people of mixed blood and immigrants was announced. Twenty-one marriage immigrant family support centers (currently multicultural family support centers) were established nationwide. In 2007, the Basic Act on the Treatment of Foreigners in Korea was enacted, and in March 2008, ‘The Multicultural Family Support Act’ was enacted. In November 2008, ‘measures to strengthen customized support for each life cycle of multicultural families’ were announced, and in 2009, the Multicultural Family Policy Committee (Chairperson: Prime Minister) was set up. In 2010, the Prime Minister's Office and related ministries jointly established and announced the 1st Multicultural Family Support Policy Basic Plan (2010–2012) (

5). In February 2012, through the revision of the Multicultural Family Support Act (

1), the Multicultural Family Support Policy Basic Plan has acquired a legal status. The Multicultural Family Support Policy Basic Plan has become a statutory plan that is revised every 5 years, and includes matters relating to basic direction, development policies, and evaluation by sector, system improvement, and financial resources and allocation, etc. The 2nd Multicultural Family Support Policy Basic Plan (2013–2017) was finalized in December 2012 (

6).

There are reports on the health and medical status of pregnant women in MCFs before year 2009. Kim et al. (

9) published a report from the results of a questionnaire-based survey, about the experience and level of support for pregnancy and childbirth of female marriage immigrants, health and public health care status, and policy tasks of MCFs. Only 35.9% of pregnant women received support for pregnancy and childbirth. The need for support among female marriage immigrants, for pregnancy and childbirth related support services, was reported as very necessary by 30.5% of MCF females, generally required by 14.9%, usually required by 12.5%, and scarcely required by 19.6%, indicating that about half of them were in need of support (

10,

11). The report presented that among the challenges for married immigrant women, the first was maternal, and child health, especially delayed first antenatal care. The second challenge was maternal and child nutrition, with a high number of low nutritional status and anemic women, and the third challenge was health care and nurturing of the baby (

12). It was suggested that there is a high need to strengthen maternal immigrant women's support and education, and access to information for maternal, child health, and perinatal care. In 2012, Lee et al. (

13) suggested the need for a special management system for MCFs, for support during perinatal, obstetric, neonatal, pediatric, and adolescent periods, through statistical review and policy framework. The plan to support maternal and child health services for international marriage immigrant women, and the 1st Multicultural Family Support Policy Basic Plan (2010–2012) (

5), and 2nd Multicultural Family Support Policy Basic Plan (2013–2017). Multicultural family support centers were created for improving the health and medical care of pregnant women, women during childbirth, and newborn infants. From our results in 2015, neonatal BW and GA in MCF birth showed no adverse outcomes compared to KF birth, and preterm births were lower in MCF than in KF. In BW and GA of newborn infants, MCF has no adverse birth outcomes compared to KF. Many factors such as uterine malnutrition, socio-economic factors, medical risks before or during gestation, and maternal race/ethnicity may contribute to birth outcomes (

1415). Maternal body weight at the time of becoming pregnant and the early development of the placenta determine the fetal growth (

16). The proportion of premature and low BW babies has been rising in Korea due to advanced maternal age and multiple pregnancy or assisted conception (

17). This situation in Korea may have affected the birth outcomes regardless of the nutritional status of Koreans.

The number of MCF marriages and the percentage of total marriages in Korea have decreased from 36,629 (11.2%) in 2008 to 22,462 (7.4%) in 2015 (

4). Among MCF, marriage between Korean men and international women was the highest at 62.6%, followed by Korean women married to international men (22.9%), and others including the naturalized people (14.6%) in 2015. In 2015, among men with multicultural marriage, 22.7% were in the age group of 45 years and above, 21.8% were in their early thirties and 19.1% were in their late 30s. While the ratio of men over 45 has declined, the ratio of those in their late 20s and early 30s is increasing. Among women who married in a multicultural society, 29.8% were in their late 20s, followed by early 30s (21.2%) and early 20s (18.7%). The percentage of those over 35 years old is declining, and the proportion of those in their late 20s and early 30s shows an increasing trend. In 2015, the average age of first marriage was 35.4 years for men and 27.9 years for women. The average age gap at first marriage between men and women who married in MCFs was 7.5 years. In multicultural marriage, male-seniority couples accounted for 77.5%, female-seniority couples accounted for 16.5%, and matching age couples accounted for 6.0%. The number of multicultural marriages was in the following order: Gyeonggi-do (5,720 cases), Seoul (5,007 cases), and Gyeongnam-do (1,240 cases). Among the male foreign nationals in multicultural marriages, China had the highest nationality (9.7%), followed by the United States (7.3%) and Japan (3.6%), and among women, China also had the highest nationality of 27.9%, followed by Vietnam (23.1%) and the Philippines (4.7%).

The number of multicultural births and the multicultural percentage among total births increased from 13,443 (2.9%) in 2008 to 22,908 (4.7%) in 2012, to 21,290 (4.9%) in 2013, and the total number and percentage decreased to 19,729 (4.5%) in 2015. Among the multicultural births, the first child accounted for 53.0%, followed by 37.7% for the second, and 9.6% for the third or above. In terms of births by multicultural type, Korean father and mother of foreign nationality accounted for 65.2%, followed by others (19.6%), and father with foreign nationality and Korean mother (15.2%). In multicultural births, the proportion of births by mother's age was: 25–29 years, 31.6%; 30–34 years, 30.0%; and 20–24 years, 20.1%. The proportion of persons under 25 years of age showed a steady decline, while the proportion of people in their 30s increased. The average age at birth of the mother in multicultural birth was 29.0 years for the first child, 30.1 years for the second child, and 32.0 years for the third child or above. Multicultural parents had a marriage period of 2.1 years until birth of the first child and 65.5% of the children who had married life less than 2 years until the first birth. The number of multicultural births by region was 5,222 births in Gyeonggi-do, 3,745 births in Seoul, and 1,357 births in Gyeongnam-do. According to births by parents' nationality, China as foreign nationality of the father was 6.7%, followed by the US (4.9%) and Japan (1.9%), and for foreign nationality of the mother, Vietnam was the highest (32.6%), followed by China (23.6%) and the Philippines (8.4%).

The number of children (aged 18 or younger) in MCFs increased from 44,258 persons in 2007 to 207,693 persons in 2014 and decreased to 197,550 persons in 2015 (

2). In 2015, the distribution of children by age group was 116,068 (58.7%) under 6 years of age, 61,625 (31.2%) between 7–12 years, 12,567 (6.4%) between 13–15 years, 7,290 persons (3.7%). Thus, the proportion of children lower than the age for elementary school enrollment is 58.7%, indicating that the average age is low.

The limitation of this study is the rate of disease prevalence and mortality and/or neonatal mortality were not calculated due to incomplete data on diseases and deaths. Comparing the prevalence of disease between MCF and KF and the mortality rate or neonatal mortality rate by diseases could be the objective of further studies in future.

In conclusion, this study compared several birth related factors between MCF and KF in 2015, based on the recent status of MCF marriages and births in Korea. The hypothesis that MCF has higher proportion of adverse neonatal outcomes compared to that of KF was proved untrue. The average BW and GA in MCF and KF groups were similar, while the frequency of preterm birth classified as high risk, was less in MCF despite the low education level of parents and high frequency of out-of-hospital deliveries. This is due to the government support for perinatal medical system through implementation of the basic plan of family support policy, including measures to strengthen customized support for each MCF based on the stage of life cycle. This study provides important basic data on the births in MCF and the situation in neonatal care in 2015. Subsequent studies on the infantile disease and neonatal death among MCF births are necessary.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download