INTRODUCTION

Publication delay of scientific papers is a well-known problem. Whereas the actual measurement has hardly been reported in scholarly publications, we could refer to the Björk and Solomon's work (

1) in 2013. From ‘Satoshi Village,’ a famous blog on science general, we could also refer to the exact measurement of publication lag in 3,475 articles published by PLOS (

2), and in 3 million or more PubMed (

http://www.pubmed.gov/; National Library of Medicine. Bethesda, MD, USA) articles (

3). However, these resources do not provide specific insight regarding the situation in Korea.

Publication delay is not only an inconvenience for authors, but also an impediment to the timeliness of science, and also a chore for editors to overcome for journal efficiency. For example, we identified an anthropological paper that was published 40 months after the start of the study (

4) and a molecular biology paper that was published after 4 years and 7 months; adding an additional 3 years to the research (

5). These examples of time lag make us skeptical regarding how much these papers will contribute to the advancement of science. Publication delays are a problem for both authors and editors.

The Korean Association of Medical Journal Editors (KAMJE) journals have been rapidly globalizing in recent years despite their long history. The KoreaMed Synapse is the front-end gateway and reference linking platform established by the KAMJE as a part of the globalization that opens to worldwide readers. An editor of a member journal had published the very first data summary (

6) for its publication lag, as an announcement of a journal reformation through online-first publication. Yet, for other KAMJE journals, a tangible report regarding publication delay never materialized.

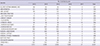

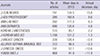

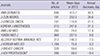

In this study, the authors investigated the timestamps of KAMJE journals over the past four years. By categorizing total publication delay by acceptance lag and lead lag, the authors aimed to give the KAMJE journals insights regarding their efficiency and fuel them to take proper measures to reduce the publication delay.

DISCUSSION

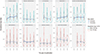

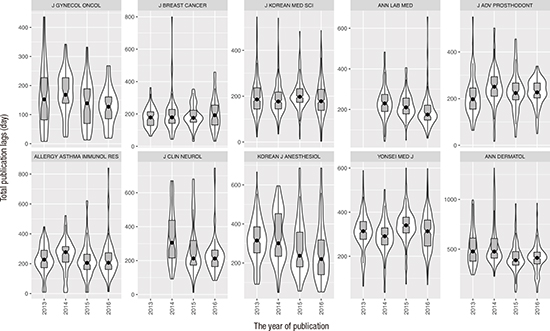

At a glance, the present result showed one detail encouraging to the KAMJE editors. The total publication delay of the KAMJE journals decreased during the period targeted by this experiment. The reduction in the total publication lag was due solely to the shortening of the lead lag. As the acceptance lag, on average, became negligibly shorter recently, we devoted a good deal of space in the present manuscript to proclaim that the failed effort on acceptance lag will come to the KAMJE journals as the next hurdle.

We adopted a seemingly sophisticated method to analyze year trend of the lags. As mixed-effects modeling treated journals as a source of random variation and allowed the inter-journal variability to be strictly normalized, which produced a safe result for expanding discussion over all KAMJE journals (

10). We preferred to view the inter-journal difference as random and avoided disputing why and how much there were differences according to the journal identity. The estimates of slopes (annual changes) for the lags were meant to indicate a population prediction, which truly did not indicate forecasting but a collective output amounted by what policies journals had taken and what circumstances they had coped with.

The lead lag, days between acceptance and publication, showed wide variability both between journals and between the year of publication. Reduction of the total publication lag relied definitely on reduction of the lead lag. A sound speculation exists for the reduction of the lead lag in which the change was technical, including a recent introduction of online-first publication and redesign of a flow of manuscripts in many KAMJE journals. Thus, in order to shorten the lead lag, every journal can take the same above plan irrespective of its identity or discipline, and are urged to reform weak segments in the process. They will get a decent opportunity to reduce lead lag.

Failure in reducing acceptance lag is intriguing to KAMJE editors. That was the one that they most deplored in the results. Editors should pay attention to the fact that acceptance lag and lead lag amounted to total publication lag by the same weight. Average length of the acceptance lag of the KAMJE journals was drifting over the same range with that of the PubMed journals, 100–150 days (

3). It occurs to us that medical journals had already reached a limit of efficiency of traditional peer review, so calling it, “a glass ceiling.” Scheer (

11) raised credible concerns about incompleteness and slowness of the traditional review system, based on an authors' survey framed by the Nature Publishing Group in 2014 (

12).

Forgetting the P value, narrower CI pertaining to the acceptance lag suggests that our estimation on the acceptance lag was much more precise than the lead lag (13.2 vs. 21.2 days). Moreover, narrow variability in acceptance lag between journals (ICC [acceptance] = 0.25) also supports journal identity-dependent factor takes scarcely into account in reducing that lag. The narrow variability in itself strongly indicated an actual difference in peer review system was small between the KAMJE journals, opposed to the previous instance of the lead lag.

Prolongation of peer review is associated with increasing number of papers worldwide and growing number of interdisciplinary research, whose improvement should be shared by authors, reviewers, and editors (

13). We, however, stuck to emphasizing the role of the editors, not only because of its importance but because of our primary focus. If the lead lag depends on a technical aspect of the journal publication, the acceptance lag is subject to the elementary conditions about efficient peer review systems, starting with triaging manuscripts, identifying a good reviewer, educating them, encouraging and rewarding them (

1415), publishing guidelines, improving a review process, and more. An editorial authored by Gasparyan (

16) summarized a good list of a few strategic efforts for editors to promote a big difference in delivering successful editing and publishing.

It was evident that the KAMJE editors have dedicated to reducing the lead lag for boosting journal efficiency and it is likewise clear that now is the time to attempt to reduce the acceptance lag. While the traditional peer review system faces a lot of doubt and challenge, we do not have the single most efficient peer review system possible. The KAMJE journals are administered by pure academic societies of medicine that confers the journals on a unique status, opposed to other medical journals published abroad. Thus, the KAMJE journal editors have to use their initiative to change everything on the journal quickly based on the needs of the journal, regardless of profit-generation. They have spent much time probably on changing page layout, designing the cover, and revamping the flow of the manuscript from authors to XML-depositor, until now. They have to spend much more time to advance the process of peer review.

In a sense, our approach was not fair. The result was concocted from journals of different types of publication; that is, online-first publication, online publication after print, and the recently commencing online-only publication. According to Alves-Silva et al. (

17), publication delay was significantly linked to journal identity, the amount of publications per journal, and inversely the journal impact factor, none of which were included in this research. Another limitation also lurked in the raw dataset. The Crossref metadata had some errors in the timestamp, from whichever they originated. While the only issue we could address was falsely negative calculation of the lag values that was ruled out, other issues still might be hidden in the dataset. We found it hard to design code for locating all types of errors. Furthermore, it was a voluntary option for submitting the publication history to the Crossref; that was the main reason why the final dataset contained just 10 of the 17 journals; that also posed a question about selection bias between journals that provided timestamps or not.

We limited the subject of this research to the so-called ‘journal articles,’ categorized as either original articles or case reports. Types of articles not included in the research might be editorials or reviews or opinions, which, to our knowledge, were not eligible for regular peer review, or at least, published after a dedicated process other than regular review, in some journals. Including them in the analysis would have ruined our purpose and contaminated the results. Actually, we could easily find that some journals omitted the timestamps of those articles.

Moreover, throughout the manuscript, we were saying the timestamps of ‘the KAMJE journals’ instead of saying ‘the KAMJE Scopus journals.’ Developing and debugging the R code, enormous PMIDs obtained from random KoreaMed Synapse articles were attempted and yielded a bad return because those timestamps were often blank in the Crossref pages. Putting a limit to the Scopus journals yielded a good return, finally we had to scrape articles of the KoreaMed Synapse journals indexed in the Scopus. It was inevitable to acquire good timestamps.

We reported a cross-section of the publication delay of the last 4 years by investigating 10 KAMJE journals. The KAMJE journals have reduced the total publication delay entirely by means of reducing the lead lag, not by reducing the acceptance lag. Along with their struggle over the lead lag, editors must encourage further accelerated peer review processes. This finding warrants a consistent follow-up, driven by the editors.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download