1. Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005; 83:661–669.

2. Clarkson JJ, McLoughlin J. Role of fluoride in oral health promotion. Int Dent J. 2000; 50:119–128.

3. Hujoel PP. Endpoints in periodontal trials: the need for an evidence-based research approach. Periodontol 2000. 2004; 36:196–204.

4. Saintrain MV, de Souza EH. Impact of tooth loss on the quality of life. Gerodontology. 2012; 29:e632–6.

5. Yang SE, Park YG, Han K, Kim SY. Association between dental pain and tooth loss with health-related quality of life: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e4707.

6. Joshipura KJ, Willett WC, Douglass CW. The impact of edentulousness on food and nutrient intake. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996; 127:459–467.

7. Naito M, Yuasa H, Nomura Y, Nakayama T, Hamajima N, Hanada N. Oral health status and health-related quality of life: a systematic review. J Oral Sci. 2006; 48:1–7.

8. Barbosa TS, Gavião MB. Oral health-related quality of life in children: part II. Effects of clinical oral health status. A systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008; 6:100–107.

9. Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF. Tooth loss, chewing ability and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2008; 17:227–235.

10. Chambrone LA, Chambrone L. Results of a 20-year oral hygiene and prevention programme on caries and periodontal disease in children attended at a private periodontal practice. Int J Dent Hyg. 2011; 9:155–158.

11. Nuvvula S, Chava VK, Nuvvula S. Primary culprit for tooth loss!! J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2016; 20:222–224.

12. Ribeiro LS, Dos Santos JN, Ramalho LM, Chaves S, Figueiredo AL, Cury PR. Risk indicators for tooth loss in Kiriri Adult Indians: a cross-sectional study. Int Dent J. 2015; 65:316–321.

13. Ogawa H, Yoshihara A, Hirotomi T, Ando Y, Miyazaki H. Risk factors for periodontal disease progression among elderly people. J Clin Periodontol. 2002; 29:592–597.

14. Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2004; 34:9–21.

15. Lee JH, Choi JK, Kim SH, Cho KH, Kim YT, Choi SH, et al. Association between periodontal flap surgery for periodontitis and vasculogenic erectile dysfunction in Koreans. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2017; 47:96–105.

16. Lee JH, Oh JY, Youk TM, Jeong SN, Kim YT, Choi SH. Association between periodontal disease and non-communicable diseases: a 12-year longitudinal health-examinee cohort study in South Korea. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96:e7398.

17. Choi JK, Kim YT, Kweon HI, Park EC, Choi SH, Lee JH. Effect of periodontitis on the development of osteoporosis: results from a nationwide population-based cohort study (2003–2013). BMC Womens Health. 2017; 17:77.

18. Singhrao SK, Harding A, Simmons T, Robinson S, Kesavalu L, Crean S. Oral inflammation, tooth loss, risk factors, and association with progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014; 42:723–737.

19. Lee JH, Kweon HH, Choi JK, Kim YT, Choi SH. Association between periodontal disease and prostate cancer: results of a 12-year Longitudinal Cohort Study in South Korea. J Cancer. 2017; 8:2959–2965.

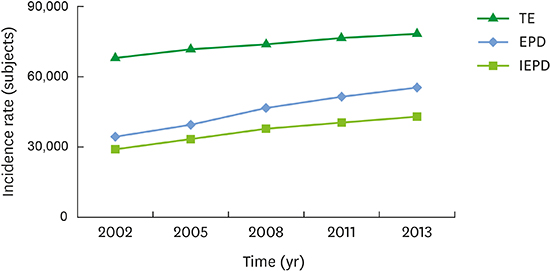

20. Lee JH, Lee JS, Choi JK, Kweon HI, Kim YT, Choi SH. National dental policies and socio-demographic factors affecting changes in the incidence of periodontal treatments in Korean: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study from 2002–2013. BMC Oral Health. 2016; 16:118.

21. Benjamin RM. Oral health: the silent epidemic. Public Health Rep. 2010; 125:158–159.

22. Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999; 4:1–6.

23. Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007; 78:1387–1399.

24. Celeste RK, Nadanovsky P, de Leon AP, Fritzell J. The individual and contextual pathways between oral health and income inequality in Brazilian adolescents and adults. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 69:1468–1475.

25. Lee JH, Lee JS, Park JY, Choi JK, Kim DW, Kim YT, et al. Association of lifestyle-related comorbidities with periodontitis: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94:e1567.

26. Celeste RK. Contextual effect of socioeconomic status influences chronic periodontitis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2007; 7:29–30.

27. Palmier AC, Andrade DA, Campos AC, Abreu MH, Ferreira EF. Socioeconomic indicators and oral health services in an underprivileged area of Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2012; 32:22–29.

28. Park HJ, Lee JH, Park S, Kim TI. Changes in dental care access upon health care benefit expansion to include scaling. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2016; 46:405–414.

29. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health care resources: dentists [Internet]. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development;cited 2017 May 17. Available from:

http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=30177#.

31. Buchwald S, Kocher T, Biffar R, Harb A, Holtfreter B, Meisel P. Tooth loss and periodontitis by socio-economic status and inflammation in a longitudinal population-based study. J Clin Periodontol. 2013; 40:203–211.

32. Kim DW, Park JC, Rim TT, Jung UW, Kim CS, Donos N, et al. Socioeconomic disparities of periodontitis in Koreans based on the KNHANES IV. Oral Dis. 2014; 20:551–559.

33. Borges CM, Campos AC, Vargas AM, Ferreira EF. Adult tooth loss profile in accordance with social capital and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Cien Saude Colet. 2014; 19:1849–1858.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download