1. Noar SM, Chabot M, Zimmerman RS. Applying health behavior theory to multiple behavior change: considerations and approaches. Prev Med. 2008; 46(3):275–280.

2. Conner M, Norman P. Predicting health behaviour. 2th ed. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press;2005.

3. Weinstein ND, Rothman AJ, Sutton SR. Stage theories of health behavior: conceptual and methodological issues. Health Psychol. 1998; 17(3):290–299.

4. Cohen JH, Kristal AR, Stanford JL. Fruit and vegetable intakes and prostate cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000; 92(1):61–68.

5. McTiernan A. Behavioral risk factors in breast cancer: can risk be modified? Oncologist. 2003; 8(4):326–334.

6. Rachet B, Siemiatycki J, Abrahamowicz M, Leffondré K. A flexible modeling approach to estimating the component effects of smoking behavior on lung cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004; 57(10):1076–1085.

7. Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Speizer FE. Relation of meat, fat, and fiber intake to the risk of colon cancer in a prospective study among women. N Engl J Med. 1990; 323(24):1664–1672.

8. Rohde K, Boles M, Bushore CJ, Pizacani BA, Maher JE, Peterson E. Smoking-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among Alaska Native people: a population-based study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013; 72(1):72.

9. Strasser AA, Tang KZ, Tuller MD, Cappella JN. PREP advertisement features affect smokers' beliefs regarding potential harm. Tob Control. 2008; 17:Suppl 1. i32–i38.

10. Wilson N, Weerasekera D, Peace J, Edwards R, Thomson G, Devlin M. Misperceptions of “light” cigarettes abound: national survey data. BMC Public Health. 2009; 9(1):126.

11. Xu X, Liu L, Sharma M, Zhao Y. Smoking-related knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, smoking cessation idea and education level among young adult male smokers in Chongqing, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015; 12(2):2135–2149.

12. Yong HH, Borland R, Cummings KM, Hammond D, O'Connor RJ, Hastings G, et al. Impact of the removal of misleading terms on cigarette pack on smokers' beliefs about ‘light/mild’ cigarettes: cross-country comparisons. Addiction. 2011; 106(12):2204–2213.

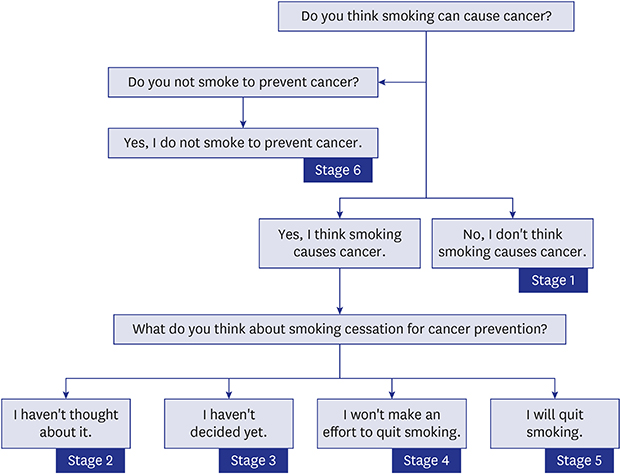

13. Weinstein ND, Sandman PM. The precaution adoption process model and its application. In : DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: strategies for improving public health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass;2002. p. 16–39.

14. Newson RS, Elmadfa I, Biro G, Cheng Y, Prakash V, Rust P, et al. Barriers for progress in salt reduction in the general population. An international study. Appetite. 2013; 71:22–31.

15. Stein K, Zhao L, Crammer C, Gansler T. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of beliefs regarding cancer risks. Cancer. 2007; 110(5):1139–1148.

16. Adlard JW, Hume MJ. Cancer knowledge of the general public in the United Kingdom: survey in a primary care setting and review of the literature. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2003; 15(4):174–180.

17. Brunswick N, Wardle J, Jarvis MJ. Public awareness of warning signs for cancer in Britain. Cancer Causes Control. 2001; 12(1):33–37.

18. Koo JH, Arasaratnam MM, Liu K, Redmond DM, Connor SJ, Sung JJ, et al. Knowledge, perception and practices of colorectal cancer screening in an ethnically diverse population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010; 34(5):604–610.

19. Fernandez R, Rolley JX, Rajaratnam R, Everett B, Davidson PM. Reducing the risk of heart disease among Indian Australians: knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding food practices - a focus group study. Food Nutr Res. 2015; 59:25770.

20. Smith ML, La Place LL, Menn M, Wilson KL. HIV-related knowledge and perceptions by academic major: implications for university interventions. Front Public Health. 2014; 2:18.

21. Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: an AIDS risk reduction model (ARRM). Health Educ Q. 1990; 17(1):53–72.

22. Rodgers AB, Kessler LG, Portnoy B, Potosky AL, Patterson B, Tenney J, et al. “Eat for Health”: a supermarket intervention for nutrition and cancer risk reduction. Am J Public Health. 1994; 84(1):72–76.

23. Bauer HH, Reichardt T, Barnes SJ, Neumann MM. Driving consumer acceptance of mobile marketing: a theoretical framework and empirical study. J Electron Commerce Res. 2005; 6(3):181.

24. Nigg CR, Burbank PM, Padula C, Dufresne R, Rossi JS, Velicer WF, et al. Stages of change across ten health risk behaviors for older adults. Gerontologist. 1999; 39(4):473–482.

25. Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Lewis BP. Modeling condom-use stage of change in low-income, single, urban women. Res Nurs Health. 2002; 25(2):122–134.

26. Heydari G, Yousefifard M, Hosseini M, Ramezankhani A, Masjedi MR. Cigarette smoking, knowledge, attitude and prediction of smoking between male students, teachers and clergymen in Tehran, Iran, 2009. Int J Prev Med. 2013; 4(5):557–564.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download