This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

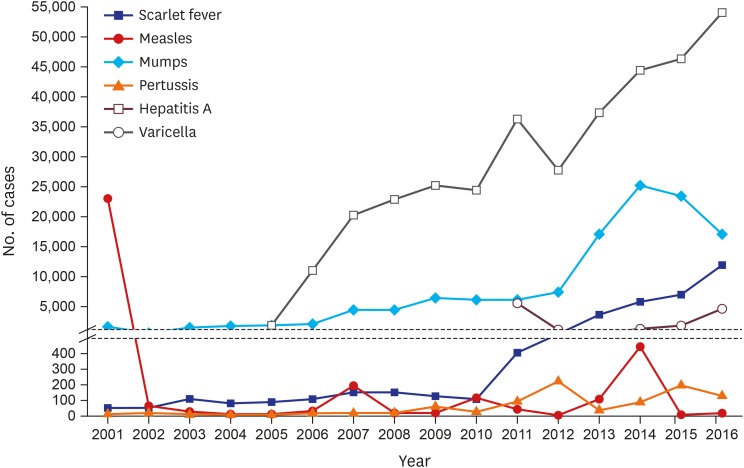

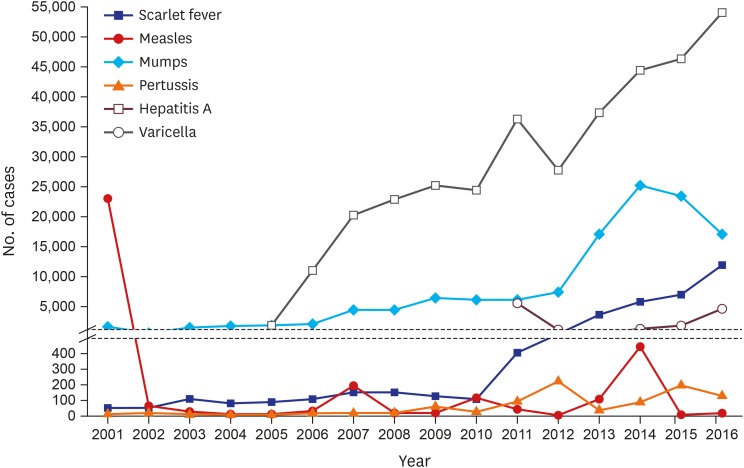

Can you imagine deaths from liver failure after a hepatitis A viral (HAV) infection? Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis long after contracting measles? Infertility or subfertility from mumps? Varicella even after vaccinated for it, increasing zoster in all ages? These ailments are rare but well-known complications of each corresponding infectious disease, but they were hardly observed since the last decade because of the effective disease control with upgraded hygiene, well-programmed vaccination and antibiotics usage. (

Fig. 1)

Unfortunately, these complications may be on the verge of returning. Mumps and varicella vaccines are included among national immunization program (NIP), but 17,057 and 54,060 cases of infections were reported in 2016, respectively.

1 They have been reported increasingly every year from the mid-2000s. Scarlet fever, caused by group A streptococcal infection, had limited cases reported until 2010, but with increasing cases thereafter and 11,911 cases in 2016.

1 HAV infection was not an important pathogen until the 1970s–1980s because almost all persons were infected in early ages with low sequelae by poor hygienic environment. They had immunity to HAV and there was no need for vaccination at those time. However rapid increases of HAV from 1,197 cases in 2012 to 4,679 cases in 2016 were reported with an outbreak with 5,521 cases in 2011.

1 Some of HAV cases were imported from overseas by abroad travelers. What's next? Measles, pertussis, and more? We should not make these infectious diseases as “never-ending stories,” and comprehensive global preparedness for preventing outbreaks is needed urgently.

We already know that vaccine program pursues high rate of vaccination. According to the report from Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) in 2016, vaccination rates between 0 and 3-year-old children for national essential vaccination were over 90%; BCG 97.8%, HepB 97.3%, DTaP 96.2%, IPV 97.6%, MMR 97.8%, Var 97.5%, JE 92.7%.

2 The vaccination rate in NIP was reported in young ages but there is little nation-wide survey data of their appropriateness of immune formation to prevent infection after vaccination. We do not know why mumps and varicella are continuously and increasingly prevalent in spite of high vaccination rates. Is it from a vaccine procedure failure or genetic changes of causative agents? It is impossible to answer this question immediately because there is little basic background data in Korea. We habitually adopt the data of infection status, seroepidemiological data from other advanced countries when an outbreak occurs without our own continuous and routine investment for the basic infection data. If they were utilized without global understanding or analyzed without the comparison with our own data, it would not always help to resolve our need because the situation of each country is different from each other.

We already know changes much in genetic characteristics of many causative pathogens, nutrition, individual and herd immunity, ways of domestic and international transportation, socioeconomical and environmental situation from the past ones. Therefore, it is imperative that a global and comprehensive preparedness mechanism be implemented, not only for the emerging infectious diseases but also re-emerging, “forgotten” ones.

The KCDC is the sole entity responsible for the control of legal reporting of communicable diseases in the country, but it has limited resources and faces an uphill battle in realizing complete preparedness for all infectious diseases. We have already learned a difficult lesson from the dearth of infectious diseases specialists during the influenza epidemic in 2009 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in 2015. It is true that, in response to these crises, the Korean Government has reformed the structure of KCDC and increased its workforce to more effectively control emerging infectious diseases. However, old-fashioned infectious diseases, scarlet fever, mumps, hepatitis A, varicella, and zoster are in resurgence. It is necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of pathogens, hygiene levels, immunity status and changes in each age group, environmental alterations, dietary nutrition, vaccine supply, treatment modalities, international relationship of diseases, so on. In order to make and keep Korea safe from infectious diseases, we must expend every effort to go beyond the current fragmented approaches to institute a more balanced framework predicated on a mutually-reinforcing, cross-sectoral network of stakeholders. This would necessitate, inter alia, strengthening the planning and implementation capacities of Korean Government including KCDC, enhancing the participation of regional government bodies, supporting academic research at universities, infectious disease institutes and related entities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was performed using literature and services at the Seoul National University College of Medicine.

References

1. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infectious Diseases Surveillance Yearbook, 2016 (PHWR Vol 10-GL2017001). Cheongju, Korea: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017.

2. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Childhood Vaccination Coverage among Children Aged 3 Years in Korea, 2016. Cheongju, Korea: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017.