Dear Editor:

Syphilis is the Great Masquerader and a syphilitic gumma is now extremely rare type of tertiary syphilis, which is easy to be misdiagnosed and requires high suspicion index.

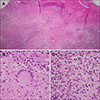

A 48-year-old woman presented with a painless ulcerated plaque on her face for 2 months. At another hospital, she had been treated with antibiotic and antiviral therapies with repetitive dressings, which was not successful. She was previously healthy and denied trauma and skin cancer history. Physical examination showed a 4×4 cm crater-shaped plaque with crusts and oozing (Fig. 1A). We received the patient's consent form about publishing all photographic materials. Provisional diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum and squamous cell carcinoma. Skin biopsy demonstrated extensive necrosis and large areas of granulomatous inflammation within the dermis (Fig. 2A), including numerous multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 2B) and marked lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (Fig. 2C). A rapid plasma regain test was reactive (1:16), and fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) tests for immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G were both positive. A human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative. Only then did the patient mention that she was inadequately treated for syphilis 20 years ago. Taken together, she was finally diagnosed with a syphilitic gumma. Further work up including cerebrospinal fluid analysis did not reveal any evidence of internal organ involvement. The lesion was significantly improved after three intramuscular injections of 2.4 million units of penicillin G (Fig. 1B). Since then she has become lost to follow-up.

Almost one-third of patients with primary or secondary syphilis who were untreated can develop the late manifestations such as cutaneous syphilis, neurosyphilis, or cardiovascular syphilis1. Cutaneous tertiary syphilis accounts for about 16% of them1. The time to progress to tertiary syphilis varies from several months to 35 years after infection23. When dealing with patients associated with HIV, it should be kept in mind that HIV may modify the natural course and therapeutic response of syphilis, making the patients vulnerable to an accelerated progression2. Cutaneous tertiary syphilis can be divided into two forms. A noduloulcerative type, the more common variant, occurs as superficial, flat nodules or plaques which progressively grow to build a serpiginous configuration resembling granuloma annulare. The second, a gumma is appears as a non-tender nodular lesion with central punched-out necrosis, exhibiting the deeper and more destructive features1. Histologically, both contain granulomas with large aggregates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells. However, caseation necrosis is rarely observed in noduloulcerative lesions but extensively found in gummas3. Silver stains or immunohistochemical stains for Treponema pallidum are not sensitive due to the scarcity of the organism3.

As cutaneous tertiary syphilis clinically simulates many other skin diseases, its diagnosis should depend on a comprehensive interpretation of the patient's medical history, pathologic findings, and serology results. An excellent response to intramuscular benzathine penicillin G (3 weekly) can give an additional guarantee of the diagnosis4. When it manifests as an oral lesion, it is sometimes difficult to determine the stages. Especially, the primary oral syphilis required differential diagnosis. However, it usually occurs as a solitary chancre involving the lips and tongue which develops within 1 to 3 weeks after direct contact with a syphilitic patient5. Because FTA-ABS IgM can be positive regardless of the stages, FTA-ABS test is not useful in distinguishing the stages. In the present case, the history of having syphilis 20 years ago and having no recent suspicious contact helped us diagnose the patient as cutaneous tertiary syphilis.

Although the prevalence of syphilis has continued to decline, the late manifestation from patients who had syphilis in the past can constantly emerge. Thus, awareness of this unusual clinical presentation is necessary to appropriately diagnose and treat patients with cutaneous tertiary syphilis.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Benzaquen M, Horreau C, Koeppel MC, Berbis P. A pseudotumoral facial mass revealing tertiary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017; 42:714–716.

2. Rocha N, Horta M, Sanches M, Lima O, Massa A. Syphilitic gumma--cutaneous tertiary syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004; 18:517–518.

3. Boyd AS. Syphilitic gumma arising in association with foreign material. J Cutan Pathol. 2016; 43:1028–1030.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download