Abstract

Purpose

Materials and Methods

Results

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

References

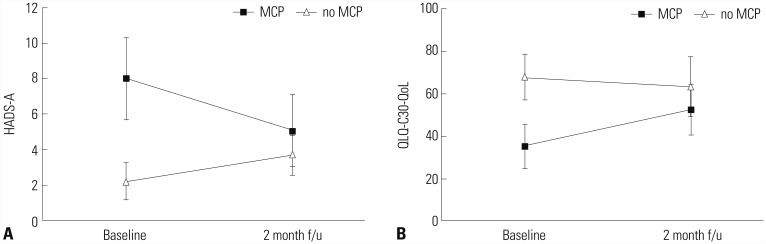

Fig. 1

Comparison of changes from baseline to 2 months after MCP. The MCP and non-MCP groups showed significantly different changes between the initial and final assessments in the scores of (A) HADS-A (p=0.007) and (B) QLQ-C30-QoL (p=0.017). MCP, meaning-centered psychotherapy; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale; QLQ-C30-QoL, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30, global quality of life subscale; f/u, follow-up.

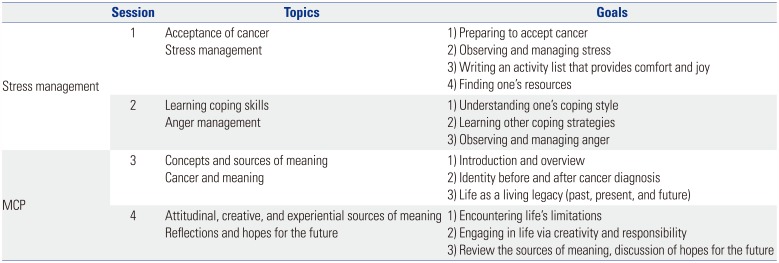

Table 1

Weekly Topics and Goals of MCP

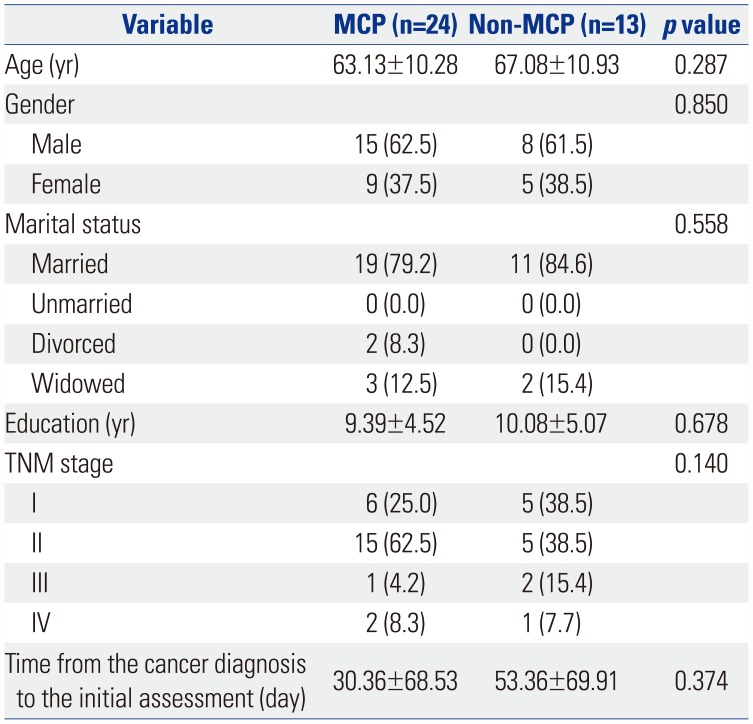

Table 2

Patient Demographic Data

Table 3

Comparison of Baseline Emotional Distress and QoL between MCP and Control Groups

MCP, meaning-centered psychotherapy; DS-DT, National Comprehensive Cancer Network distress thermometer; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale; HADS-D, HADS, Depression subscale; MAC, Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale; HH, helpless-hopeless; FS, fighting spirit; AP, anxious preoccupation; FA, fatality; CA, cognitive avoidance; QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30; PF, physical function; RF, role function; EF, emotional function; CF, cognitive function; SF, social function; QoL, global quality of life; QLQ-PAN26, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire pancreatic cancer-specific module; Pain, pancreatic pain; Bowel, altered bowel habit; Body, body image; Satisfaction, satisfaction with health care; Sexual, sexual functioning; SRRS, Social Readjustment Rating Scale; 6m, within 6 months life change unit; 7–12m, 7–12 months life change unit; Sum, life change unit summation.

Data are presented as a mean±standard deviation.

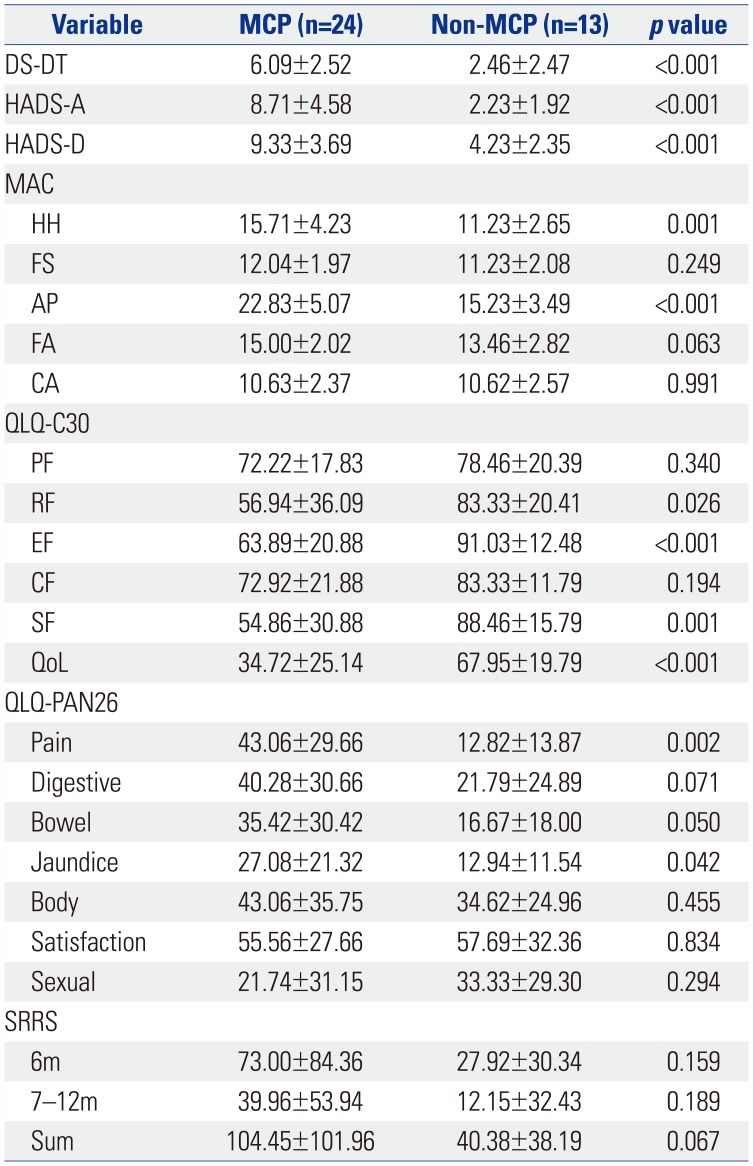

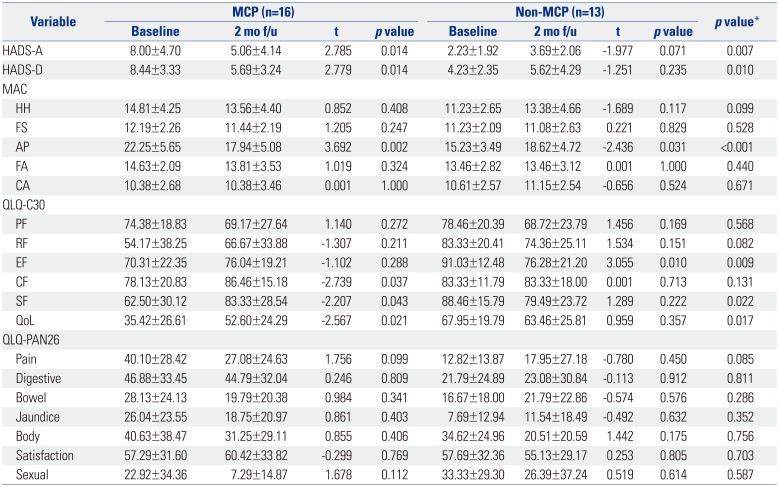

Table 4

Changes in Scores for Psychological Assessment of MCP and Control Groups

MCP, meaning-centered psychotherapy; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale; HADS-D, HADS, Depression subscale; MAC, Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale; HH, helpless-hopeless; FS, fighting spirit; AP, anxious preoccupation; FA, fatality; CA, cognitive avoidance; QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30; PF, physical function; RF, role function; EF, emotional function; CF, cognitive function; SF, social function; QoL, global quality of life; QLQ-PAN26, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire pancreatic cancer-specific module; Pain, pancreatic pain; Bowel, altered bowel habit; Body, body image; Satisfaction, satisfaction with health care; Sexual, sexual functioning.

Data are presented as a mean±standard deviation.

*p value from independent T-test comparing the differences of initial assessment and 2 months later between the MCP and non-MCP group.

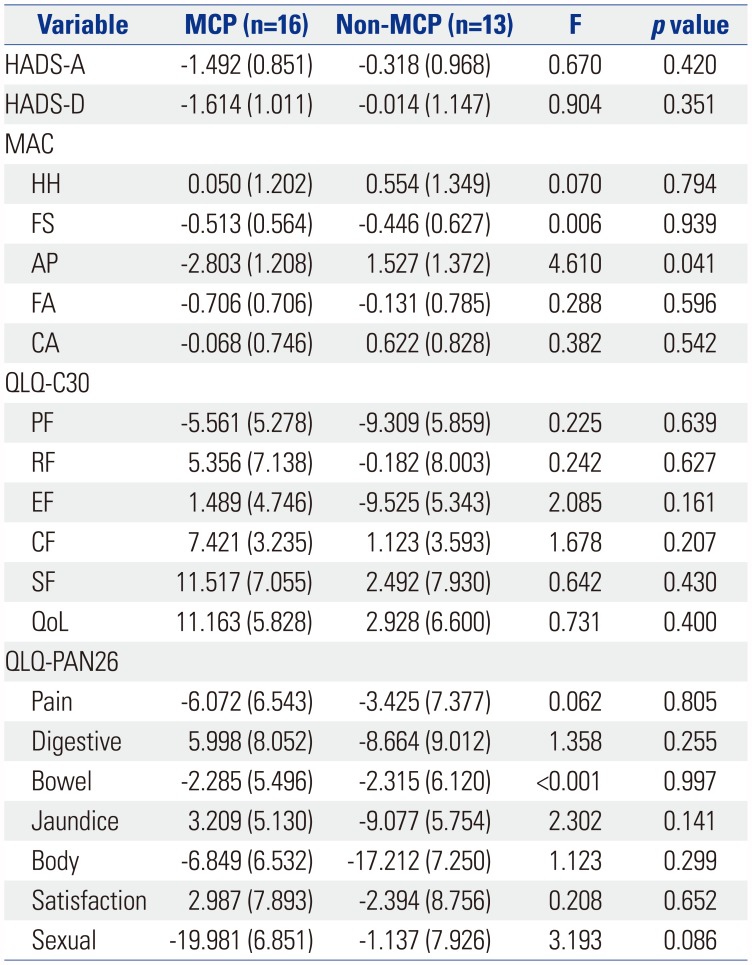

Table 5

Results for Changes in Scores for Psychological Assessment in MCP and Control Groups by ANCOVA

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; MCP, meaning-centered psychotherapy; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale; HADS-D, HADS, Depression subscale; MAC, Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale; HH, helpless-hopeless; FS, fighting spirit; AP, anxious preoccupation; FA, fatality; CA, cognitive avoidance; QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30; PF, physical function; RF, role function; EF, emotional function; CF, cognitive function; SF, social function; QoL, global quality of life; QLQ-PAN26, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire pancreatic cancer-specific module; Pain, pancreatic pain; Bowel, altered bowel habit; Body, body image; Satisfaction, satisfaction with health care; Sexual, sexual functioning.

Data are presented as an estimated marginal mean (standard error of the mean). Score changes with negative values in the HADS-A, HADS-D, MAC-HH, AP, and CA and positive values in the MAC-FS, FA, and QLQ-C30 items represent improvement.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download