Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the underlying causes and clinical characteristics of patients referred with intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who were referred with IOP elevation from July 2016 to July 2017. Patients with baseline IOP ≥ 22 mmHg and those who were treated and followed up for 6 months were included. The prevalence rates of the underlying diseases that caused IOP elevation were evaluated and the clinical characteristics were compared between patients with primary and secondary glaucoma.

Results

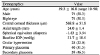

A total of 127 patients were included (mean age, 59.3 ± 16.8 years; baseline IOP, 31.7 ± 10.5 mmHg). Among the study participants, 22.0%, 31.5%, and 46.5% had been diagnosed with ocular hypertension, primary glaucoma, and secondary glaucoma, respectively. Among the causes of IOP elevation, open-angle glaucoma (20.5%) had the highest prevalence rate among those with primary glaucoma and inflammation-related glaucoma (12.6%) was the most prevalent cause among those with secondary glaucoma. In a comparison between patients with primary and secondary glaucoma, the percentage of IOP reduction was not significantly different at 6 months after treatment (52.1% vs. 53.9%, p = 0.603). However, the rate of patients treated with drugs other than IOP lowering agents or who underwent surgery was significantly higher in the secondary glaucoma group compared with the primary glaucoma group (all p < 0.05). At 6-month follow-up, the secondary glaucoma group showed significantly higher improvement rates of visual acuity (p = 0.004), but had a larger proportion of patients with a visual acuity of less than or equal to finger count (p = 0.027).

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Prevalence rate of underlying causes for intraocular pressure elevation. Open-angle glaucoma showed the highest prevalence rate (20.5%) among primary glaucoma and inflammation-related glaucoma (12.6%) among secondary glaucoma. G = glaucoma. |

References

1. Colton T, Ederer F. The distribution of intraocular pressures in the general population. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980; 25:123–129.

2. Leydhecker W, Akiyama K, Neumann HG. Intraocular pressure in normal human eyes. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd Augenarztl Fortbild. 1958; 133:662–670.

3. Sharrawy T, Sherwood M, Hitchings R, Crowston J. Glaucoma. 2nd ed. Vol. 1:Elsevier Ltd.;2015. p. 325–731.

4. Quigley HA, Addicks EM, Green WR, Maumenee AE. Optic nerve damage in human glaucoma. II. The site of injury and susceptibility to damage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981; 99:635–649.

5. Nickells RW, Howell GR, Soto I, John SW. Under pressure: cellular and molecular responses during glaucoma, a common neurodegeneration with axonopathy. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012; 35:153–179.

6. European Glaucoma Society Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma, 4th Edition - Chapter 3: Treatment principles and options Supported by the EGS Foundation: Part 1: Foreword; Introduction; Glossary; Chapter 3 Treatment principles and options. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017; 101:130–195.

7. Shazly TA, Latina MA. Neovascular glaucoma: etiology, diagnosis and prognosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2009; 24:113–121.

8. Siddique SS, Suelves AM, Baheti U, Foster CS. Glaucoma and uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013; 58:1–10.

9. Moon Y, Sung KR, Kim JM, et al. Risk factors associated with glaucomatous progression in pseudoexfoliation patients. J Glaucoma. 2017; 26:1107–1113.

11. Baskaran M, Foo RC, Cheng CY, et al. The prevalence and types of glaucoma in an urban chinese population: The Singapore Chinese Eye Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015; 133:874–880.

12. Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Sun X. Epidemiologic characteristics of 10 years hospitalized patients with glaucoma at shanghai eye and ear, nose, and throat hospital. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e4254.

13. Cho HK, Kee C. Population-based glaucoma prevalence studies in Asians. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014; 59:434–447.

14. Kyari F, Entekume G, Rabiu M, et al. A Population-based survey of the prevalence and types of glaucoma in Nigeria: results from the Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015; 15:176.

15. Foster PJ, Oen FT, Machin D, et al. The prevalence of glaucoma in Chinese residents of Singapore: a cross-sectional population survey of the Tanjong Pagar district. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118:1105–1111.

16. Kim CS, Seong GJ, Lee NH, et al. Prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in central South Korea the Namil study. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:1024–1030.

17. Kim KE, Kim MJ, Park KH, et al. Prevalence, awareness, and risk factors of primary open-angle glaucoma: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2011. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123:532–541.

19. Al-Bahlal A, Khandekar R, Al Rubaie K, et al. Changing epidemiology of neovascular glaucoma from 2002 to 2012 at King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017; 65:969–973.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download