This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Chemodenervation with botulinum toxin (BTX) has been recommended for focal spasticity. BTX injection should be performed with caution in patients with bleeding disorders and/or receiving anticoagulation therapy. We present a case of BTX injection for post-stroke spasticity in a patient with hemophilia A who could not take oral spasmolytics due to chronic hepatitis C. To minimize the bleeding risk, we replaced factor VIII intravenously in accordance with the World Federation of Hemophilia guidelines for minor surgery. FVIII (3,000 IU) was administered 15 minutes before BTX injection. One day later, 2,000 IU was administered, and 2 days later, another 2,000 IU was administered. We performed the real-time Ultrasound-guided BTX injection three times, then spasticity and upper extremity function improved without adverse events. BTX injection can be considered as a treatment option for spasticity among patients with hemophilia.

Highlights

• Chemodenervation with botulinum toxin is effective for focal post stroke spasticity.

• Ultrasound-guided botulinum toxin injection was done with pre-procedural and post-procedural factor VIII administration in a hemophilia A patient.

• After the botulinum toxin injection, spasticity improved without adverse events.

Keywords: Botulinum Toxins, Spasticity, Stroke, Homophilia A, Ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Spasticity results from damage of upper motor neurons, and can cause pain, joint contracture, and restrictions to activities of daily living. Nonpharmacologic or pharmacologic treatment is available, and chemodenervation with botulinum toxin (BTX) has been recommended for focal spasticity [

1234]. However, BTX injection should be performed with caution in patients with bleeding disorders and/or receiving anticoagulation therapy according to the United States Food and Drug Administration. We report a case of BTX injection for post-stroke spasticity in a patient with hemophilia A who could not take oral spasmolytics due to chronic hepatitis C.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old man diagnosed with left hemiplegia due to intracranial hemorrhage in the right putamen in September 2014 was admitted to our hospital in April 2015. He was born with hemophilia A and had received blood transfusion of clotting factor until he was 10-year-old. Then, factor VIII (FVIII) replacement therapy (2,000 IU every 4 days) was carried out following the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) guidelines. Heterotrophic ossification occurred in right knee, left ankle, and left elbow as a result of repetitive hemarthrosis, and he had a limitation of motion of left elbow extension to 34 degrees. He also had been infected with hepatitis C virus 20 years ago, which might have been caused by transfusion of the infected clotting factor concentrates. Since then, he had been receiving regular medical follow-ups and taking oral hepatotonics.

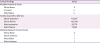

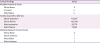

At the time of admission, the left upper limb strength was Medical Research Council scale grade 1–2, and the spasticity was Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) grade 1–2. The detailed clinical findings are presented in

Table 1. His elbow, wrist and finger flexor spasticity induced pain and hindered rehabilitation and activities of daily living, such as bathing or dressing, thus the management of spasticity was necessary.

Table 1

Baseline clinical findings of left upper limb spasticity and muscle strength

|

Clinical findings |

Value |

|

Modified Ashworth Scale |

|

|

Elbow flexor |

2 |

|

Pronator |

1+ |

|

Wrist flexor |

1+ |

|

Tardieu Scale (R1 [°]/R2 [°]) |

|

|

Elbow extension |

77/130*

|

|

Elbow flexion |

105/130 |

|

Wrist extension |

20/70 |

|

Wrist flexion |

75/80 |

|

Medical Research Council Scale |

|

|

Elbow flexor |

2 |

|

Elbow extensor |

1 |

|

Wrist flexor |

1 |

|

Wrist extensor |

1 |

However, the use of oral medication for spasticity was limited as the results of repetitive liver function tests were consistently above the normal ranges (aspartate aminotransferase, up to 80 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, up to 50 IU/L). BTX injection was also limited because of his coagulopathy. Though he wanted BTX injection for left upper limb spasticity, his previous doctors refused to perform BTX injection due to his coagulopathy. Despite fully explained bleeding risk and other possible adverse events of BTX injection, he strongly requested it. Additionally, his spasticity was getting worse hindering rehabilitation and further functional improvement along with left upper extremity pain reaching 8/10 on a numeric rating scale. Thus, we planned to perform BTX injection after obtaining written informed consent.

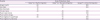

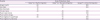

There is no guideline for BTX injection in patients with coagulopathy. To minimize the bleeding risk, we replaced FVIII intravenously in accordance with the WFH guidelines for minor surgery. FVIII (3,000 IU) was administered 15 minutes before BTX injection. One day later, 2,000 IU was administered, and 2 days later, another 2,000 IU was administered. After confirming the exact location of the target muscle and vessels, we performed the real-time US-guided injection (Accuvix XG; Medison, Seoul, Korea). Total 300 IU of Botox

® (Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) was used (

Table 2). US follow-up was conducted right after injection and there was no finding suggesting bleeding (

Fig. 1). Blood laboratory tests including the complete blood cell count were conducted at the next day of the injection and the level of hemoglobin changed from 15.4 g/dL to 15.6 g/dL. The range of motion (ROM) and MAS grades were improved when evaluated at 2 weeks and 1 month post-injection. His affected upper limb pain decreased from 8/10 to 5/10 on a numeric rating scale and dressing improved from maximal assist to moderate assist at 1 month after the injection.

Table 2

Dose of botulinum toxin injection

|

Muscles |

Dose of botulinum toxin |

|

Botox® U in the first injection |

Botox® U in the second injection |

Dysport® U in the third injection |

|

Biceps brachii |

60 |

50 |

200 |

|

Brachialis |

70 |

50 |

200 |

|

Brachioradialis |

30 |

|

|

|

Pronator teres |

40 |

40 |

100 |

|

Flexor carpi ulnaris |

|

40 |

100 |

|

Flexor pollicis longus |

20 |

20 |

50 |

|

Flexor digitorum superficialis |

80 |

70 |

250 |

|

Flexor digitorum profundus |

|

30 |

100 |

Fig. 1

Follow-up sonographic finding right after botulinum toxin injection.

After inpatient treatment for 3 months, he received outpatient follow-up. Repeated BTX injections were performed in September 2015 and January 2016: in the second injection, total 300 IU of Botox

® (Allergan Inc.) and in the third injection, total 1,000 IU of Dysport

® (Ipsen Ltd., Slough, Berkshire, UK) was used (

Table 2). The injection drug was selected based on its availability at the time of each injection. FVIII was supplied, and US-guided injection was performed under the same procedure. Like the first injection, BTX-injection related bleeding was not found with US and laboratory tests. With each injection, the ROM and spasticity improved without adverse events (

Fig. 2). After three times of the BTX injections, his affected upper limb pain decreased from 8/10 to 3/10 on a numeric rating scale and his activities of daily of living improved (dressing: maximal assist to supervision, personal hygiene: moderate assist to supervision) along with spasticity improvement of elbow flexor (MAS: 2 to 1+) and wrist flexor (MAS: 1+ to 1).

Fig. 2

The changes in the Tardieu Scale (R2–R1) after botulinum toxin injection: (A) after the first injection; (B) after the second injection; (C) after the third injection.

BTX, botulinum toxin.

DISCUSSION

We safely performed BTX injection three times for spasticity management after stroke in a patient with hemophilia A by using FVIII supplementation according to the WFH guidelines and a US-guided injection technique. The results demonstrated improvement of spasticity.

Hemophilia is an X-linked congenital bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency of coagulation factor VIII or IX. The characteristic feature of hemophilia is a bleeding tendency, and most bleedings occur internally into joints or muscles [

5]. To our knowledge, there is only one case report about BTX injection in a patient with hemophilia A for post-stroke spasticity, in which hematuria occurred after the BTX injection on upper limb. That case report hypothesized that BTX has negative effects on the coagulation cascade, given the effects of acetylcholine and norepinephrine on thrombin and fibrin [

6].

However, in our case, we minimized the bleeding risk by means of prophylaxis with intravenous injection of FVIII concentrates. FVIII concentrates are the treatment of choice for hemophilia A and act to reduce the bleeding risk. Each unit of FVIII per kilogram of body weight infused intravenously may increase the plasma FVIII level of approximately 2 IU/dL, when measured 15 minutes after the infusion [

5]. Therefore, the required amount of FVIII is calculated as follows:

The suggested plasma factor peak level for minor surgery is 50–80 IU/dL at preoperation and 30–80 IU/dL at postoperation. Moreover, subsequent dose is needed for 1 to 5 days depending on the types of procedure done. According to the above formula, our patient (weight: 72 kg) was infused with 3,000 IU/dL FVIII (72 × 80 × 1/2) 15 minutes before the injection and with 2,000 IU/dL FVIII for two consecutive days after the injection. These supplementations prevented the anticipated bleeding.

US visualizes bones, vessels, nerves, and target muscles, as well as injected fluids in real-time. US guidance aids in avoiding injections into the vascular or nerve structures, and minimizes the spread of toxin outside the target muscle belly [

7]. Therefore, US guidance is recommended for localization in BTX injection for spasticity [

89]. In our case, we minimized the bleeding risk by using US-guided BTX injection technique, as well as by providing FVIII supplementation. For these reasons, there were no adverse bleeding events after BTX injections.

Thus, BTX injection can be considered as a post-stroke spasticity management in patients with hemophilia by using an adequate factor supplementation and an accurate US guidance.