Abstract

Purpose

There is a lack of scholarly reports on pediatric emergency department (PED) exposure to hyperbilirubinemia. We aimed to describe the epidemiology of hyperbilirubinemia in patients presenting to a PED over a three-year period.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study, completed at an urban quaternary academic PED. Patients were included if they presented to the PED from 2010 to 2012, were 0 to 18 years in age, and had an elevated serum bilirubin for age. A chart review was completed to determine the incidence of hyperbilirubinemia, etiology, diagnostic work up and prognosis. The data set was stratified into four age ranges.

Results

We identified 1,534 visits where a patient was found to have hyperbilirubinemia (0.8% of all visits). In 47.7% of patients hyperbilirubinemia was determined to have arisen from an identifiable pathologic etiology (0.38% of all visits). First-time diagnosis of pathologic hyperbilirubinemia occurred in 14% of hyperbilirubinemia visits (0.11% of all visits). There were varying etiologies of hyperbilirubinemia across age groups but a male predominance in all (55.0%). 15 patients went on to have a liver transplant and 20 patients died. First-time pathologic hyperbilirubinemia patients had a mortality rate of 0.95% for their initial hospitalization.

Conclusion

Hyperbilirubinemia was not a common presentation to the PED and a minority of cases were pathologic in etiology. The etiologies of hyperbilirubinemia varied across each of our study age groups. A new discovery of pathologic hyperbilirubinemia and progression to liver transplant or death during the initial presentation was extremely rare.

Pediatric hyperbilirubinemia (HB), an elevation of serum bilirubin above age-adjusted norms, has a myriad of possible etiologies [1]. Some of these etiologies represent significant underlying disease while others represent more benign processes [2]. There is a surprising lack of scholarly reports on pediatric emergency department (PED) exposure to HB and its' varying etiologies.

It is the challenge of the pediatric emergency medicine physician to identify HB and then distinguish pathologic from nonpathologic forms [3]. An aid to assist physicians in this distinction would be an assessment of the current epidemiology and etiologies of HB patients presenting to the PED. There are several studies in the literature related to the specific epidemiology and emergency medical management of neonatal HB [456]. However, the authors are unaware of any publications that assess the epidemiology and etiologies of HB presenting to the PED across all ages and diagnoses.

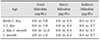

After obtaining approval for the study from the institutional review board, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of all eligible patients that presented to an urban quaternary academic PED. Patients were included in the study if they presented to the PED from 2010 to 2012, were 0 to 18 years in age, and had an elevated serum bilirubin (Table 1). As this study was retrospective, any patients who did not have a serum bilirubin ordered by the provider during their PED stay were naturally excluded.

The researchers used the electronic medical record to identify patients who had an elevated serum bilirubin discovered in the PED setting. We then reviewed the patient's charts for medical history, physical examination, laboratory results, diagnostic imaging reports, surgical consultation notes, histopathology, admission data, discharge diagnoses, patient outcomes, and future clinic notes.

This large data set was compiled to determine epidemiological data and stratified into four age ranges to reflect age related changes in epidemiology (neonates, 0 to 8 weeks; infants, 8 weeks to 1 year; young children, 1 year to 6 years; and older children, 6 to 18 years). The researchers then reviewed the data in an effort to determine the incidence of HB, morbidity and mortality, and, when possible, the etiology. The etiology outcome of the study was defined as a diagnosis that can be found in the International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) that could be reasonably attributed as the cause of the patient's HB.

The algorithm for determining reasonably attributable etiologies for a patient's HB in our cohort is outlined below: The investigators reviewed the aforementioned data set. They then determined if an etiology was reasonably attributable based on the known natural progression of the disease process, the patient's clinical presentation, laboratory results, and diagnostic imaging. If a reviewer came across a HB patient where the etiology was unclear or they had questions about a disease process, then the case was re-reviewed by the study's hepatologist for final assessment. Patients who lacked an identifiable etiology after this review process were identified as such in the results.

All cases of elevated direct HB (greater than 20% of total bilirubin) represent pathological HB, as these cases always represent an underlying significant disease process. Indirect HB cases could be found to be pathological, non-pathological (benign), or of unknown etiology.

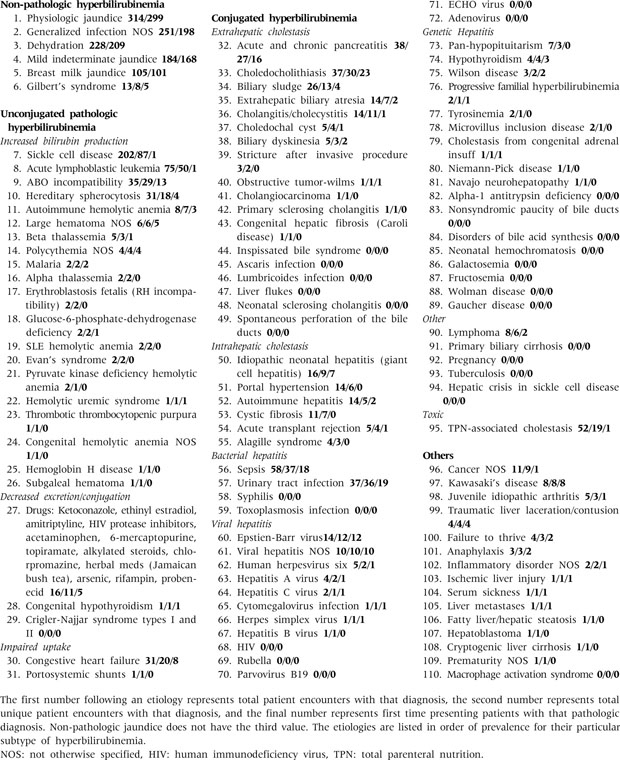

We identified six different etiologies of HB that were non-pathological. There are two types of benign HB associated with breast-feeding in young infants. The first is known as physiologic jaundice, which is early onset, and related to caloric deprivation and/or insufficient feeding of newborns [5]. The second is breast milk jaundice, which has a later onset, and is associated with abnormalities of the maternal milk itself [5]. Physiologic jaundice was determined to be the etiology in infants less than two weeks of age with no other identifiable etiology. Breast milk jaundice was determined to be the etiology in breastfed infants older than two weeks but less than eight weeks of age with no other identifiable etiology. Generalized infection not otherwise specified (NOS) was any child with symptomatology of a simple viral or bacterial process that had no other explanation for HB and did not meet criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis. SIRS and sepsis criteria were based on the American College of Critical Care Medicine definitions [7]. Dehydration was determined to be the etiology of HB when the treating physician documented dehydration and there was no other likely etiology after review of the records. Patients with mild elevations in bilirubin (less than 1 µg/dL above age corrected norms) and no clear cause were categorized as “mild indeterminate HB”. Finally, any patient who was diagnosed with Gilbert's syndrome by a pediatric hepatologist or gastroenterologist was considered benign HB (see discussion section for more information on Gilbert's).

The collected data was coded and logged into spreadsheets. Epidemiological trends of HB and its' various underlying etiologies were extrapolated in the context of the four age ranges (Appendix 1).

We identified 1,534 total visits (1,236 unique patients, 55.0% male) where a patient was found to have HB, which represented 0.8% of total PED patient visits (190,079) over the three years (Table 2). In 47.7% (732) of the patients, HB was determined to have arisen from an identifiable pathologic etiology. The remaining 52.3% of patients either had a non-pathologic etiology or an etiology that could not be determined. A first time diagnosis of pathologic HB (no known history of pathologic HB) occurred in 13.8% (211) of HB patient visits and in 0.1% of all PED patient visits. The aforementioned groups of HB patients, stratified by age, are presented in Fig. 1. The gap between all HB and pathologic HB on the figure is attributable to the six non-pathologic causes of HB we discussed as well as those who did not have an identifiable pathologic etiology which most likely represented underlying Gilbert's mild hemolysis or other benign causes. We identified 75 different etiologies of HB in our cohort out of the 110 possible etiologies we were evaluating for.

For all patients in the study, the 5 most common diagnoses were jaundice (299), dehydration (174), mild indeterminate HB (168), generalized infection NOS (136), and breast milk jaundice (101). The five most common etiologies for any visit with identifiable pathologic HB were sickle cell disease (202), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (72), sepsis (58), total parenteral nutrition associated cholestasis (52), and pancreatitis (38). The five most common etiologies for first time identifiable pathologic HB were choledocholithiasis (23), urinary tract infection (19), sepsis (18), pancreatitis (16), and neonatal blood type incompatibility (12).

In the neonatal age range (0 to 8 weeks), 6.7% of all PED visits were discovered to have HB. This age group was 58% male, represented 31.6% (484) of the total PED HB visits, and 37.2% (460) of unique PED HB visits. In this group, the five most common etiologies of HB for any visit were physiologic jaundice (299), breast milk jaundice (90), generalized infection NOS (42), dehydration (35), and ABO incompatibility (27). In the neonatal group first time pathologic HB was found in 8.7% (42) of HB patients and accounted for 20% of the total first time HB in the cohort. The five most common etiologies for first time identifiable pathologic HB were ABO incompatibility (12), urinary tract infection (9), congestive heart failure (4), sepsis (3), and idiopathic neonatal hepatitis (3). It should also be noted that the important diagnosis of biliary atresia was seen 14 times over the study period in 7 unique patients, and 2 times it was diagnosed for the first time in the PED.

In the infant group (8 weeks to 1 year), 0.3% of all PED visits were discovered to have HB. This age group was 57% male, represented 5.9% (91) of the total PED HB visits, and 5.4% (67) of the unique PED HB visits. In this group, the five most common etiologies of HB for any visit were generalized infection NOS (13), breast milk jaundice (11), mild indeterminate HB (10), dehydration (9), and total parenteral nutrition associated cholestasis (7). In the infant group first time pathologic HB was found in 22.0% (20) of HB patients and accounted for 10% of the total first time HB in the cohort. The five most common etiologies for first time identifiable pathologic HB were idiopathic neonatal hepatitis (4), total parenteral nutrition associated cholestasis (4), sepsis (3), urinary tract infection (3), and sickle cell disease (3).

In the young child group (1 to 6 years), 0.2% of all PED visits were discovered to have HB. This age group was 57% male, represented 11.7% (179) of the total PED HB visits, and 10.6% (131) of the unique PED HB visits. In this group, the five most common etiologies of HB for any visit were generalized infection NOS (33), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (21), sickle cell disease (19), dehydration (17), and mild indeterminate HB (15). In the child group, first time pathologic HB was found in 16.2% (29) of HB patients and accounted for 14% of the total first time HB in the cohort. The five most common etiologies for first time identifiable pathologic HB were Kawasaki's disease (6), viral hepatitis NOS (3), hereditary spherocytosis (2), Epstein Barr Virus (2), and sepsis (2).

In the older child group (6 to 18 years), 1.1% of all PED visits were discovered to have HB. This age group was 53% male, represented 50.8% (780) of the total PED HB visits, and 46.8% (578) of the unique PED HB visits. In this group, the five most common etiologies of HB for any visit were mild indeterminate jaundice (136), dehydration (113), sickle cell disease (64), generalized infection NOS (48), and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (25). In the older child group, first time pathologic HB was found in 15.4% (120) of HB patients and accounted for 57% of the total first time HB in the cohort. The five most common etiologies for first time identifiable pathologic HB were choledocholithiasis (22), acute or chronic pancreatitis (16), sepsis (12), Epstein-Barr virus (10), and viral hepatitis NOS (6).

Fifteen of the patients in our cohort eventually went on to have a liver transplant with inciting etiologies including autoimmune hepatitis (5), extrahepatic biliary atresia (4), viral hepatitis NOS (2), alagille syndrome (1), cystic fibrosis (1), tyrosinemia (1), and progressive familial HB (1). First time pathologic jaundice patients identified in the PED in our cohort eventually required a liver transplant in 4 patients, representing 1.9% of all such patients. First time patients requiring liver transplant were diagnosed with viral hepatitis NOS (2), extrahepatic biliary atresia (1), and progressive familial HB (1).

Twenty patients with pathologic HB from our cohort have since died, with the most common causes of death being sepsis (10) followed by congestive heart failure (3). See Table 3 for a list of patient deaths. Many of these sepsis deaths occurred in patients with significant underlying pathology for example, 9 of the 20 patients had an underlying oncological condition. Of first time pathologic jaundice patients identified in the PED, there were only 2 deaths during their immediate hospitalization. These deaths were attributed to neonatal herpes simplex virus encephalitis and ischemic liver injury from a prolonged submersion. First time pathologic jaundice patients identified in the PED in our cohort had a mortality rate of 0.95% for their immediate hospitalization.

When stratified by age, a bimodal distribution of frequency of HB was demonstrated (Fig. 1). There was a higher prevalence of HB in children less than 6 months of age (most non pathological) and those greater than 9 years of age (more pathological). There was a male predominance noted across all age groups. Interestingly, most patients were not reported by the caregivers to have jaundice. Most pathologic HB patients were admitted and the majority for more than 3 days. Only a small minority of patients required a surgical intervention with the most common surgical procedure being endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Infants were more likely to have only a bilirubin ordered but it was more likely to be fractionated. Older children tended to not have a fractionated test ordered but typically had many additional labs ordered.

Bilirubin is the product of heme catabolism that occurs as red blood cells, which contain hemoglobin, are cleared from the body. It initially exists in an unconjugated form until processed by the liver where a molecule of glucuronic acid is added making it conjugated bilirubin. Total serum bilirubin (TSB) represents the combination of unconjugated (indirect) and conjugated (direct) bilirubin. Jaundice or icterus, is a yellow-green discoloration of the skin, eyes, mucous membranes, and body fluids that results from excessive serum bilirubin [4]. Jaundice becomes clinically evident in infants when TSB exceeds 5 µg/dL and in older children when TSB exceeds 2 to 3 µg/dL [3].

There are numerous processes that can cause a benign elevation in bilirubin, whereas in pathologic HB, the elevation in bilirubin is a symptom or a byproduct of a more clinically significant underlying condition [2]. The most common causes of pathologic HB include hemolytic processes (indirect HB), extrahepatic obstruction (i.e., biliary atresia, choledochal cyst, choledocholithiasis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis, etc.) or intrahepatic obstruction caused by various genetic, metabolic, infectious, and toxic causes [2]. Conjugated, or direct HB (cholestasis), is defined as a conjugated bilirubin greater than 1 mg/dL or when the conjugated portion of the TSB exceeds 20% [2]. This cholestatic type of HB universally represents an underlying pathologic process and a timely as well as accurate diagnosis of these conditions is required to prevent significant morbidity and mortality [2].

Despite the myriad of different etiologies of HB, it is rarely discovered in the PED. Only 0.8% of patients during our 3-year sample demonstrated this finding. Furthermore, a first time diagnosis of pathologic HB was only found in 0.1% of patient visits in our cohort. We can conclude that diagnosing pathologic HB in the PED setting is quite a rare event. This may be due to the fact that patients are seen at the primary care pediatricians and are referred directly to pediatric gastroenterology/hepatology and not through the PED.

Defining “pathologic” HB proved difficult for our team, as there are so many processes that can contribute [2]. Though it has been described that dehydration and general infectious processes can cause HB, we opted to label these patients without more clear diagnoses as “non-pathologic”, owing to the somewhat subjective and transient nature of their etiologies [3]. We also elected to label patients with mild elevations in bilirubin and no clear cause “mild indeterminate HB” for similar reasons. Surely, if an exhaustive battery of tests had been employed on these patients, more patients would have been labeled more specifically. We assume that a large proportion would likely be diagnosed with the benign Gilbert's syndrome. A relatively common form of benign indirect HB found in older children prevalent in 5% to 10% of the population [8]. This syndrome is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder of bilirubin glucuronidation, characterized by recurrent episodes of benign HB that can be brought on by fasting, illness, and dehydration among others [8]. Our results demonstrate that such exhaustive testing in the PED setting is likely unnecessary and will not lead to improvements in patient's immediate outcomes.

There was a significant frequency of the diagnosis in the neonatal period, owing to physiologic jaundice and the diagnosis of genetic conditions. Less expected, was a second increase in HB frequency seen in adolescence. This increase was represented in all categories, including total cases, pathologic cases, and first time pathologic cases. Some of this rise can be attributed to pancreas and biliary pathology that was not seen in the younger populations.

When comparing the “neonatal” to the “infant” group we noticed that the “neonatal” group had far more cases of HB (484 vs. 91) but a much lower rate of first time pathologic HB (9% vs. 22%) than the “infant” group. We assume that the “neonatal” pathologic cases were washed out by benign physiologic and breast milk HB. The overall cohort had a first time pathologic HB rate of 14%. We conclude that the index of suspicion for a pathologic process should be higher when HB is discovered in the “infant” age range.

There was a male predominance across all age ranges for patients discovered to have HB in the PED. However, this predominance became less significant in the adolescent population of our cohort.

Finally, first time diagnosis of pathologic HB rarely went on to liver transplant (1.9%) or death (0.9%). Though there were other serious interventions, such as cholecystectomy and liver biopsy, it was rare to proceed to more significant morbidity and mortality.

The retrospective design of this study is limited in that patients lost to follow up could not be contacted or followed. Given the epidemiological goals of the study these patients cannot be excluded from analysis, or else the result would be an under-reporting of HB rates in the PED. It is likely that the patients lost to follow up will represent different demographics and socioeconomic features than those who have the means to attend regular gastroenterology appointments. Furthermore, one can reasonably assume, that the patients with more benign forms of HB will be less likely to be hospitalized and less likely to follow up in clinic. These patients will therefore be less likely to have an “eventual diagnosis” which could lead to an under-reporting of the more benign forms of HB. A further potential limitation, in the setting of this retrospective analysis, is that the TSB levels that were obtained may not have been fractionated into direct and indirect portions thereby limiting interpretation of the results. Finally, our patient population is 60% Latino which may limit the generalizability of this data to institutions with different demographics. These limitations, while significant, are excusable for the purposes of this study, which will serve as pilot data for a future prospective analysis.

Though a seemingly common laboratory finding with a myriad of possible etiologies, HB was encountered rarely in our PED. The etiologies of HB and the incidence of pathologic HB vary by age. Incidence of all HB and first time diagnosis of pathologic HB presenting to the PED exhibits a bimodal age distribution, with increases in patients less than 6 months and greater than 9 years of age. There is a male predominance in HB cases presenting to the PED throughout all age ranges but it becomes less pronounced in adolescence. A new discovery of pathologic HB and progression to liver transplant or death during the initial presentation was extremely rare.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Characteristics of Hyperbilirubinemia Patients Presenting to the Pediatric Emergency Department

Values are presented as percent.

Neonatal: 0–8 weeks, infant: 8 weeks–1 year, young child: 1–6 years, older child: 6–18 years.

HB: hyperbilirubinemia, ED: emergency department, ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, PT: prothrombin time, PTT: partial thromboplastin time, HIDA: hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid, MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The investigators would like to thank Phoenix Children's Hospital, and specifically the staff of the emergency, gastroenterology, and information and technology departments for their cooperation with this study.

References

1. Colletti JE, Kothari S, Jackson DM, Kilgore KP, Barringer K. An emergency medicine approach to neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007; 25:1117–1135. vii

2. Harb R, Thomas DW. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia: screening and treatment in older infants and children. Pediatr Rev. 2007; 28:83–91.

3. Miloh T, Breglio KJ, Chu J. Treatment of pediatric patients with jaundice in the ED. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2010; 7.

4. Moyer V, Freese DK, Whitington PF, Olson AD, Brewer F, Colletti RB, et al. Guideline for the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice in infants: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004; 39:115–128.

6. Shapiro SM. Bilirubin toxicity in the developing nervous system. Pediatr Neurol. 2003; 29:410–421.

7. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41:580–637.

8. Fretzayas A, Moustaki M, Liapi O, Karpathios T. Gilbert syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2012; 171:11–15.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download