INTRODUCTION

Orofacial dyskinesia is stereotyped movement, consisting of smacking and pursing of the lips, lateral deviation and protrusion of the tongue, and occasionally lateral deviation and protrusion of the jaw. And, it can lead to orofacial pain, speech difficulty, dysphagia, and the inability to wear dentures, causing problems in everyday life. Several biochemical mechanisms have been proposed as causes, and the disease is diversely categorized according to the cause or type of movement [

1].

Drugs with different action mechanisms, including haloperidol, estradiol, clonazepam, and antioxidants, have been used to treat orofacial dyskinesia, and research results have demonstrated that they had some effects [

234]. But, treatment of orofacial dyskinesia is largely with medications that, unfortunately, are not highly successful. Less than 10% of patients experienced sustained benefits from anticholinergic agents and, although neuroleptic medication may have better efficacy, the side effects and the risk of tardive manifestations prevented their general use [

5].

The occurrence of orofacial dyskinesia is accepted as due to the abnormality of various neurotransmitters, and it is known that supersensitivity of the dopamine receptors is a major cause [

6]. We have also reported complete remission in a 27-year-old male patient who had developed oral dyskinesia after a traumatic brain injury following the administration of metoclopramide [

7]. With this theoretical background and experience, we attempted to treat patients with orofacial dyskinesia using metoclopramide.

Below, we report seven cases in which an improvement in the symptoms was observed by using metoclopramide, a dopaminergic receptor blocking agent, in patients who had developed orofacial dyskinesia after suffering brain damage.

DISCUSSION

Oral dyskinesia consists of abnormal, involuntary, uncontrollable movements predominantly affecting the tongue, lips, and jaw. And, they are classified according to the phenomenology of the abnormal movements or causes; bucco-linguo-mandibular dyskinesia, oral dyskinesia, oromandibular dystonia, diurnal bruxism, tics, perioral tremor. They may go unnoticed or cause social embarrassment, oral traumatic injury, speech difficulty, chewing and eating disorders, inability to wear prosthetic devices [

1].

Prior to the seven cases described above, we had already reported the cases of a 51-year-old patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage, and a 36-year-old patient with involuntary diurnal bruxism from a traumatic brain injury, whose symptoms had been successfully managed with the administration of metoclopramide [

8]. We had also reported complete remission in a 27-year-old male patient who had developed oral dyskinesia after a traumatic brain injury following the administration of metoclopramide [

7].

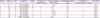

In this case reports, we tried metoclopramide in seven patients who developed oral dyskinesia after stroke. And, we have described demographic characteristics and clinical information of seven case patients in

Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics and clinical information of case series

|

Patient |

Age (yr) |

Sex |

Diagnosis |

MMSE |

Duration of symptom (mon) |

Time to symptom after stroke |

Metoclopramide dose (mg) |

Duration of metoclopramide use (mon) |

Side effect |

|

1 |

84 |

F |

Left hemiplegia |

19 |

1 |

4 mon |

30 |

8 |

None |

|

2 |

64 |

M |

Left hemiplegia |

22 |

2 |

4 yr |

30 |

5 |

None |

|

3 |

84 |

M |

Quadriplegia |

2 |

3 |

2 yr |

30 |

1 |

None |

|

4 |

78 |

F |

Left hemiplegia |

6 |

1 |

1 mon |

30 |

4 |

None |

|

5 |

75 |

F |

Quadriplegia |

1 |

1 |

3 mon |

20 |

1 |

None |

|

6 |

48 |

M |

Quadriplegia |

29 |

1 |

4 mon |

15 |

5 |

None |

|

7 |

88 |

F |

Right hemiplegia |

9 |

3 |

20 yr |

20 |

3 |

None |

The causes of orofacial dyskinesia are currently unclear. However, in order to discuss why we used metoclopramide, we need to see why orofacial dyskinesia has been developed.

Among orofacial dyskinesia, Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is known to be caused by a drug. It is an iatrogenic condition that results from the long-term use of dopaminergic antagonist medication [

9]. The pathophysiology of TD is not understood but striatal dopamine receptor supersensitivity has been the traditional and oversimplistic explanation [

10]. And, the minimum length of antipsychotic drug exposure required to propose a causal relation between the dyskinesia and the offending drug, which is typically at least three months in younger individuals, can be as short as 1 month in elderly people [

1].

Second, edentulous status is thought to be a cause of oral dyskinesia, although the number of studies on this association is surprisingly low. Unlike drug-induced dyskinesia, the movements were always confined to the oral region and never dystonic, and no tongue movements were recorded when the mouth was open. Oral dyskinesia appeared only after a long period of edentulous status, an average of 12 years separating tooth extraction and the onset of oral movements. It is probable that, with time, progressive changes occurred in the mouth. Inadequate dento-oral prostheses may cause disruption of dental proprioception, resulting in dyskinetic searching movements of the oral cavity [

11].

Finally, it is not known exactly which brain lesion causes oral dyskinesia, but several lesions are known to be associated with oral dyskinesia. Motor control is a complex process that is governed by sophisticated motor circuits involving both pyramidal (cortical) and extrapyramidal (basal ganglionic and cerebellar) circuits. Motor commands are generated in the motor cortex, but BG and cerebellum closely refine these signals by acting as feedback loops to allow for smooth, accurate, coordinated movements [

12]. Neuroleptic drugs chronically block dopamine receptors in the BG. The result would be a chemically-induced denervation supersensitivity of the dopamine receptors which leads to excessive movement [

6]. And, deep brain stimulation in thalamus, thalamotomy and pallidotomy are performed for the treatment of orofacial movements disorders [

13]. Previous studies revealed that dopamine is the major neurotransmitter involved in balance of the motor output of the prefrontal cortex by maintaining an inhibitory tone, so, the hypoperfusion of the frontal lobe is closely related to orofacial dyskinesia [

14].

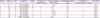

We have summarized the potential causes of orofacial dyskinesia in

Table 2 according the following categories: brain lesions, medication, and denture durations. First, when reviewing these cases, patients 2, 3, and 7 used risperidone, orofacial dyskinesia may have been caused by drugs when considering the duration of use. And, patients 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 used dentures, but considering that it takes about 12 years for orofacial dyskinesia to occur after edentulous status, the likelihood is not high. Among the brain structures, BG is known to be highly related to orofacial dyskinesia, and lesions in BG have been found in most of our patients. From these findings, we believe BG lesions are likely to be associated with orofacial dyskinesia. Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility of other potential causes as other brain regions are closely linked by numerous circuits [

12].

Table 2

Several factors related to the development of orofacial dyskinesia

|

Patient |

Brain lesions |

Orofacial dyskinesia related medication uses |

Denture duration (yr) |

|

1 |

Right parietal lobe, bilateral BG, left cerebellum |

Ropinirole 2 g and amantadine 200mg for a week before taking metoclopramide (taking metoclopramide and then stopping ropinirole and amantadine) |

5 |

|

2 |

Right MCA territory, bilateral BG and cerebellums, left pons |

Risperidone 0.5 mg for 3 years before taking metoclopramide (taking metoclopramide and then stopping risperidone) |

6 |

|

3 |

Bilateral PCA territories and cerebellums and frontal lobes, left BG, right midbrain |

Risperidone 1 mg 3 months before orofacial dyskinesia began and taking it continuously |

5 |

|

4 |

Right PICA territory and periventricular white matter, and cerebellum |

None |

5 |

|

5 |

Left MCA territory, bilateral cerebellums |

None |

Not used |

|

6 |

Both pontine |

None |

Not used |

|

7 |

Left frontal lobe, bilateral BG |

Risperidone 0.5 mg, escitalopram 10 mg for 4 years before taking metoclopramide (risperidone stopped 3 months before taking metoclopramide) |

10 |

Our patients responded well to metoclopramide, selective dopamine 2 receptor (D

2R) antagonist. Metoclopramide readily crosses the blood-brain barrier and is equal in potency to chlorpromazine in dopamine receptor blocking affinity. In mesocortical neurons, a preferential binding to presynaptic D

2R rather than postsynaptic D

2R by D

2R antagonists is noted [

15]. Metoclopramide binds to D

2R in a biphasic manner; to presynaptic D

2R at low doses and to postsynaptic D

2R with increasing doses [

16]. A selective blockade of the hypersensitive presynaptic D

2R by low dose metoclopramide recovers the dopaminergic flow and attenuates bruxism or oral dyskinesia. The absence of extrapyramidal side effects during metoclopramide therapy may be due to a higher sensitivity of mesocortical D

2R to low dose metoclopramide than that of mesolimbic or nigrostriatal neurons [

17].

Metoclopramide may also exert its effect through other mechanisms. The prefrontal cortex and ventral tegmental area have abundant noradrenergic connections. Destruction of noradrenergic fibers innervating the ventral tegmental area would result in a decrease in dopamine utilization in the prefrontal cortex, probably due to an impairment of the stimulatory a1-aderenoceptor effects on postsynaptic dopaminergic neurons. Metoclopramide may thus act through an increase in noradrenaline [

14].

In previous reports, the effect of metoclopramide appeared 3–4 hours after dosing, and in these case patients, the effect appeared 1 to 2 hours after taking pills. The degree of improvement in dyskinesia is subjective, so the difference in the time may be probably due to measurement error of time. Therefore, it will be necessary to quantitatively divide the degree of improvement and objectively suggest the time to act.

We used metoclopramide in dosages of 15–30 mg/day in seven patients who had developed orofacial dyskinesia following a brain injury and observed an improvement in the symptoms within a short time frame. This supports the hypothesis that dopamine receptors play an important role in orofacial dyskinesia, and calls for more research into unraveling the exact mechanisms. The use of metoclopramide for the treatment of orofacial dyskinesia patients is relatively safer than the administration of haloperidol. However, as metoclopramide can cause extrapyramidal symptoms, close monitoring is required.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download