Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to compare cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and digital panoramic radiography (DPR) for the detection of pulp stones.

Materials and Methods

DPR and CBCT images of 202 patients were randomly selected from the database of our department. All teeth were evaluated in sagittal, axial, and coronal sections in CBCT images. The systemic condition of patients, the presence of pulp stones, the location of the tooth, the group of teeth, and the presence and depth of caries and restorations were recorded. The presence of pulp stones in molar teeth was compared between DPR and CBCT images.

Results

Pulp stones were identified in 105 (52.0%) of the 202 subjects and in 434 (7.7%) of the 5,656 teeth examined. The prevalence of pulp stones was similar between the sexes and across various tooth locations and groups of teeth (P>.05). A positive correlation was observed between age and the number of pulp stones (ρ=0.277, P<.01). Pulp stones were found significantly more often in restored or carious teeth (P<.001). CBCT and DPR showed a significant difference in the detection of pulp stones (P<.001), which were seen more often on DPR than on CBCT.

Conclusion

DPR, as a 2D imaging system, has inherent limitations leading to the misinterpretation of pulp stones. Restored and carious teeth should be carefully examined for the presence of pulp stones. CBCT imaging is recommended for a definitive assessment in cases where there is a suspicion of a pulp stone on DPR.

Pulp stones (denticles or nodules) are discrete calcified masses that can be seen in the pulp chamber of any deciduous or permanent tooth.123 They can be found in healthy, diseased, and even unerupted or impacted teeth of all age groups.234 The most commonly affected tooth is the first molar on both jaws, followed by the second molar. The least commonly affected teeth are the incisors and canines.35 The presence of pulp stones does not affect the threshold of electric pulp testing6 and should not be considered as a disorder requiring endodontic treatment.5

The formation of pulp stone is not understood, although some etiological factors have been proposed, such as aging, pulp degeneration, inductive interactions between the epithelium and pulp tissue, genetic predisposition, long-standing irritants (caries, deep fillings, chronic inflammation, and abrasion), orthodontic tooth movement, trauma, periodontal disease, drugs, anemia, arteriosclerosis, acromegaly, and Marfan syndrome. Additionally, a high prevalence of pulp stones has been reported in patients with cardiovascular disease and kidney, gall, and salivary gland stones.4

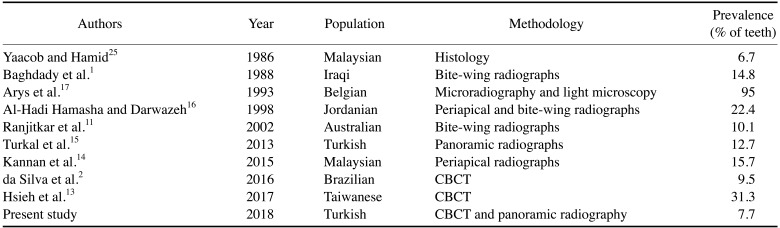

In the literature, panoramic,78 periapical,3910 bite-wing radiographs,3911 and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT)21213 have been used to evaluate the presence of pulp stones. The prevalence of pulp stones varies widely from 8% to 95%, depending on the population, study design, and radiographic method employed.34 Histology-based studies have reported higher prevalence rates than radiographic studies because calcified masses smaller than 200 µm cannot be seen on radiographs.51415 Panoramic radiography has benefits regarding the examination of all teeth at the same time with a single exposure, and it uses minimal ionizing radiation.7 It is an integral part of dental check-ups, and previous studies have revealed that pulp stones can be detected well on panoramic radiography, as well as on bite-wing and periapical radiography.78 However, 2-dimensional (2D) radiographic techniques may tend to underreport such calcifications.2 CBCT is a superior 3-dimensional (3D) imaging modality that is often used in endodontic practice to overcome the limitations of 2D techniques. It helps to manage complex endodontic problems by facilitating the separate examination of all teeth and root canals and the localization of calcified canals.2 The objective of this study was to compare CBCT and digital panoramic radiography (DPR) for the detection of pulp stones and to identify any potential correlation between the presence of pulp stones and factors such as age, sex, the tooth involved, restoration, and caries.

This retrospective study was approved by the Necmettin Erbakan University Faculty of Dentistry Research Ethics Committee and complied with the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki (decision No. 2017.11). Subjects were referred to our radiology department if they required CBCT analysis as part of their oral examination, diagnosis, and/or treatment planning.

DPR and CBCT scans of patients at least 18 years of age in whom the roots of all permanent teeth were completed were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) teeth with root resorption, 2) teeth with metal crowns, 3) teeth with previous root canal treatment, and 4) poor-quality DPR or CBCT images. Patients' characteristics (age, sex, and systemic disease) were obtained from their medical records. A total of 5,656 teeth (including all types of teeth, except for third molars) from 202 individuals were analyzed.

In all cases, DPR was performed using a panoramic unit (Morita Veraviewepocs 3D R100-P, J Morita MFG Corp., Kyoto, Japan) at 70 kVp, 10 mA, and 10 s, according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol.

CBCT images were acquired in a sitting position using a Morita 3D Accuitomo 170 device (J Morita MFG Corp., Kyoto, Japan), which was operated at 90 kVp and 5 mA, with a 17.5-s rotation time, a voxel size of 250 µm, and a 100-×100-mm field of view, according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol.

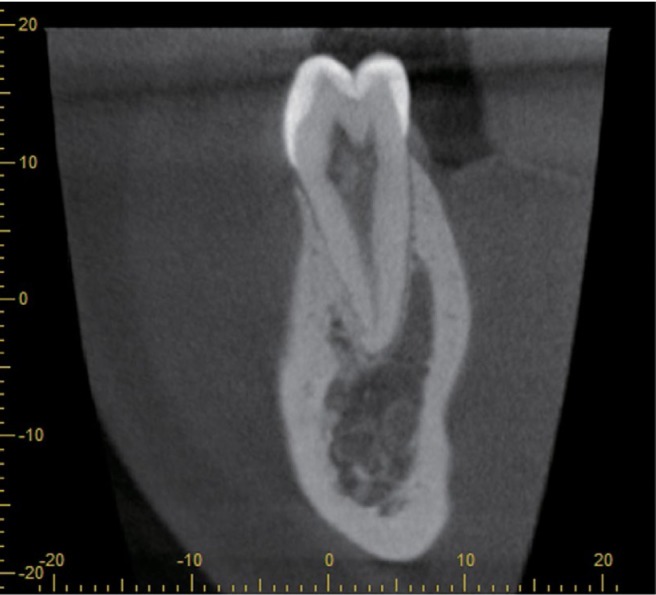

The DPR images were exported as TIFF files and evaluated by a blinded investigator with 6 years of oral and maxillofacial radiology experience in a darkened room. To view the raw data set, a 2.66 GHz Intel Xeon PC with 3.25 GB of RAM and Windows XP™ Professional operating system and a 27″ Dell U2711H™ monitor (U2711HTM; Dell, Round Rock, TX, USA) with a resolution of 2,560×1,600 pixels were used. All CBCT images were evaluated using i-Dixel software (J Morita MFG Corp., Kyoto, Japan) in all 3 planes (sagittal, axial, and coronal) on a flat-screen monitor by the same examiner (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4). For optimal visualization, the contrast and brightness of images were adjusted using the image-processing tool of the software.

Teeth were scored as having a pulp stone when a definite radiopaque mass was observed in the pulp space. The presence of a pulp stone was also analyzed according to the presence of caries and restoration, the location of the tooth, the group of teeth, and the depth of restoration and caries (superficial: up to one-third of the dentin affected, medium: one-third to two-thirds of the dentin affected, deep: two-thirds to all of the dentin affected but without pulp exposure).

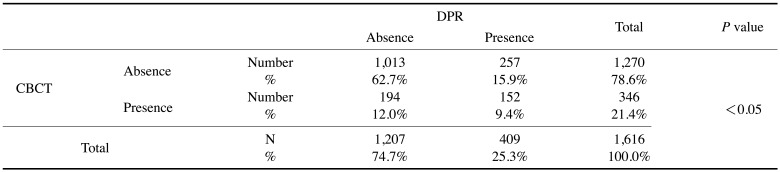

For reasons related to image quality, only the DPR and CBCT images of posterior teeth (1,616 molar teeth) were compared in terms of pulp stone occurrence.

All observations and comparisons of the DPR and the CBCT imaging modalities in terms of pulp stone identification were evaluated using the Pearson chi-square test, odds ratios, and the Cohen kappa. To test intra-examiner reproducibility, 25% of the sample was re-examined in the same manner after an interval of 30 days. The relationship between age and the presence of pulp stones was determined by the Spearman correlation test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) with a significance level of 5%.

Of the 202 individuals, 75 (37.1%) were male (mean age, 20.65±5.00 years) and 127 (62.9%) were female (mean age, 21.42±6.15 years). The mean age of the patients in the sample was 21.13±5.75 years (range, 18–53 years).

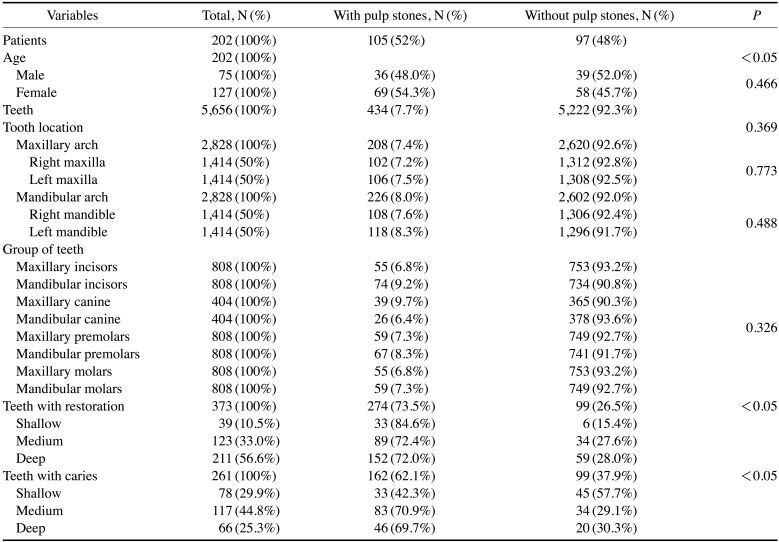

The kappa values were excellent (between 0.90 and 0.97) for all observations. The variables evaluated with regard to the presence or absence of pulp stones are described in Table 1. The prevalence of pulp stones was not significantly different by sex (P>.05). Pulp stones were detected in 105 subjects (52%) and in 434 (7.7%) of the 5,656 teeth examined. The prevalence of pulp stones in the maxillary and mandibular arches was found to be almost equal (P>.05). The occurrence of pulp stones was highest in the maxillary canines (9.7%), followed by the mandibular incisors (9.2%), and mandibular premolars (8.3%) (P>.05). The mandibular canines were the least affected group of teeth (6.4%). Teeth with restorations and caries showed a significantly higher prevalence (73.5% and 62.1%, respectively) of pulp stones than teeth without restorations or caries (P<.05).

Of the 105 patients with pulp stones, 96.2% had no systemic disease, while 3.8% had a systemic (cardiovascular, endocrine, or respiratory) disease. A positive correlation (Spearman correlation test) was observed between age and the number of pulp stones (ρ=0.277, P<.05).

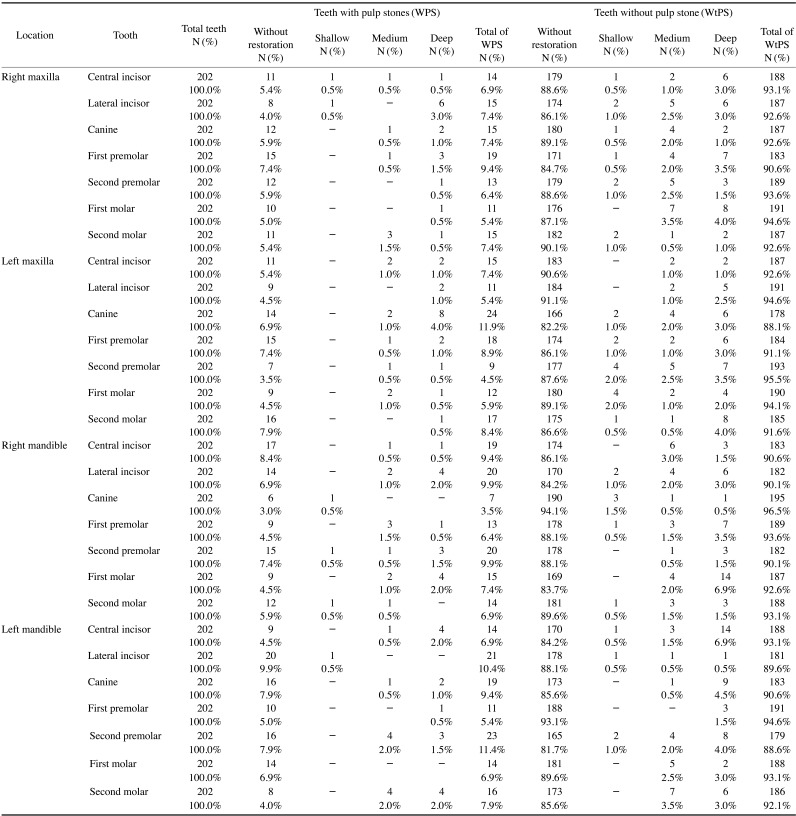

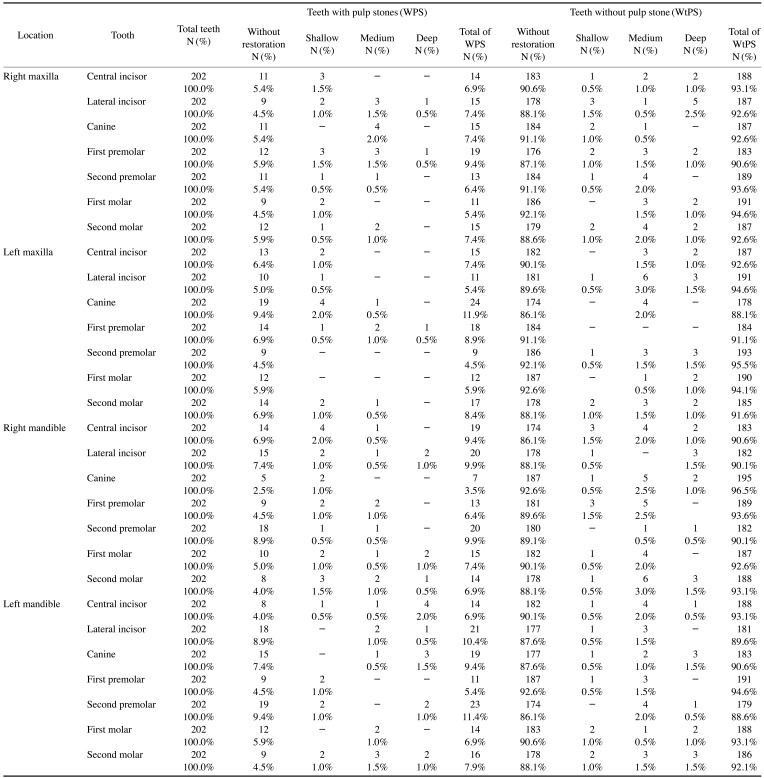

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the distribution of teeth with or without pulp stones according to tooth location, type of tooth, and depth of restoration and caries.

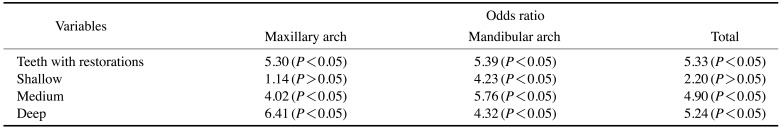

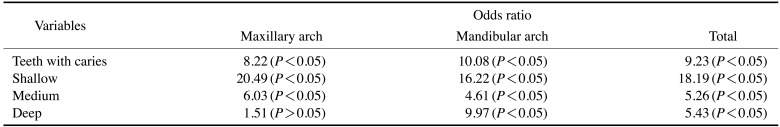

Tables 4 and 5 show the risk of the presence of these calcifications, both in all teeth and stratified between the maxillary and mandibular arches, according to the presence and type of restorations and caries. The presence of restorations and caries was associated with a higher likelihood of pulp stones by 5.33 and 9.23 times in all teeth examined, respectively (P<.05). As the depth of the restoration increased, the likelihood of pulp stone presence increased (Table 4). However, pulp stones were more frequently found in teeth with superficial caries in both the mandibular and maxillary arches (Table 5).

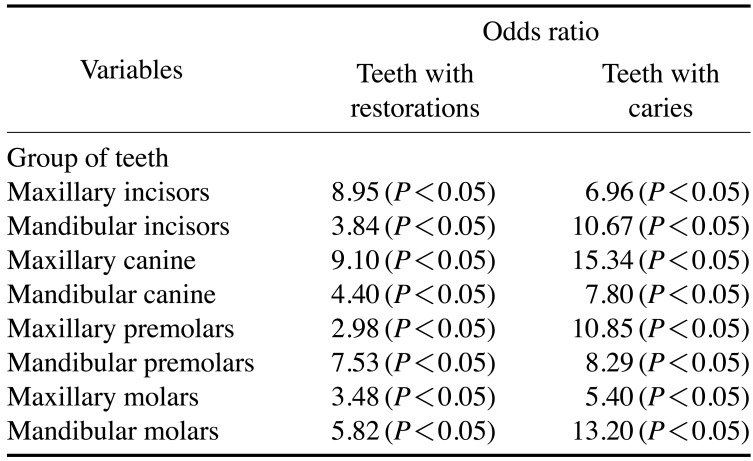

Table 6 presents the likelihood of pulp stone identification in each group of teeth in the presence of restorations and caries. Restored and maxillary canines with caries demonstrated the highest risk of occurrence of pulp stones (OR=9.10; 15.34, respectively, P<.05) compared with other tooth categories.

Overall, 9.4% of the teeth (152 of 1,616) were found to have a pulp stone by both DPR and CBCT, whereas 15.9% of the teeth (252 of 1,616) had a pulp stone that was only detected by DPR. More teeth with pulp stones were found using DPR than using CBCT (P<.05) (Table 7).

This study was performed to compare CBCT and DPR for the detection of pulp stones and to identify any potential correlation between the presence of pulp stones and age, sex, the tooth involved, restoration, and caries. Pulp stones were identified in 7.7% (434 of 5,656) of the teeth examined and 52% (105 of 202) of all individuals evaluated. This is consistent with the findings of Patil et al.,12 who used CBCT and reported a prevalence of 50.93%, and higher than the findings of da Silva et al.,2 who detected pulp stones in 31.9% of patients. Previous studies reported wide variation in the prevalence of pulp stones (from 8% to 95%) depending on the population, study design, and radiographic method employed.34 A comparison of previous studies that were conducted using various methods is presented in Table 8.

Consistent with previous research,21014 the results of this study showed that the prevalence of pulp stones did not have a statistically significant relationship with sex. Other studies contradicting our findings315 stated that more pulp stones were seen in women, which was associated with a higher prevalence of bruxism in women, which can lead to long-term irritation of the teeth.3

The current study revealed a positive correlation between age and the number of pulp stones. Additionally, it was found that the presence of restorations and caries increased the likelihood of pulp stones by 5.33 and 9.23 times in all teeth examined, respectively. Teeth with restorations and caries showed a significantly higher prevalence (73.5% and 62.1%, respectively) of pulp stones than teeth without restorations or caries. Chronic irritations such as restoration and tooth caries, as well as parafunctions, have been suggested to be predisposing factors for pulp stone formation.3 Other studies in the literature31617 have reported that pulp stones were not related to age. However, the duration, intensity, and frequency of those irritations may also be crucial. Therefore, there is a need for longitudinal studies in which radiographic follow-up is performed in patients in order to resolve this issue.3

The results of this study indicated that as the depth of restoration increased, the risk of pulp stone occurrence increased, in accordance with da Silva et al.,2 who used CBCT for pulp stone evaluation in their study. This may be explained through the hypothesis that chronic pulpal irritation leads the pulpodentinal complex to form pulp stones as a defense reaction.2314 Deeper restorations may cause greater irritation closer to the pulp and more vascular wall injuries.2 However, it was found that pulp stones were more likely to be detected in teeth with superficial caries in both the mandibular and maxillary arches. This can be explained in terms of the design of this study. This was a cross-sectional study and we had no information about how long the teeth had been exposed to the caries. This can be considered a limitation of this study. Even if the caries were superficial, the duration of the irritants may have played a crucial role.3 Furthermore, our study sample was relatively limited, and further prospective studies are needed to confirm this result.

The present study found that the prevalence of pulp stones in the maxillary and mandibular arches was almost equal. This finding is consistent with some studies,21214 but not with others.111618 The distribution of pulp stones according to the group of teeth did not show any statistically significant trends. The prevalence of pulp stones was highest in the maxillary canines (9.7%), followed by the mandibular incisors (9.2%) and mandibular premolars (8.3%), and lowest in the maxillary incisors and maxillary molars (6.8%). This may be attributed to the relatively limited sample size, and further investigations are required. Contrary to our findings, previous studies111121316 reported that pulp stones were mostly observed in molar teeth. Most studies were conducted with only posterior teeth, which could lead to an overestimation of the actual prevalence.3 Furthermore, the radiological method is an important consideration. Both anterior and posterior teeth should be examined to determine the prevalence of pulp stones. CBCT is a relatively new imaging method in endodontic practice that allows all teeth to be examined separately in different views, which is useful for localizing calcified canals.19 This method overcomes the superimposition of structures and has been found to be the best technique for the examination of pulp stones.2 Although histological analysis provides reliable results, it is only useful as an ex vivo method.20 Since pulp stones may obscure or change the root canal anatomy and lead to a poorer outcome of root canal treatment, using CBCT to determine whether pulp stones are present has been argued to be justified.2

The present study indicated that the number of teeth with pulp stones was higher on DPR than on CBCT, as 9.4% of teeth with pulp stones (152 of 1,616) were detected on both DPR and CBCT, whereas 15.9% (252 of 1,616) were detected only on DPR. DPR, as a projectional form of radiography, may overestimate or underestimate the prevalence of pulp stones8 due to image distortion and superimposition. The spatial resolution of an imaging method is defined as its capability to resolve fine details.21 Because of its low spatial resolution and 2D nature,22 DPR might not able to define pulp stones as well as CBCT. CBCT overcomes the superimposition of structures and has been found to be the best technique for the examination of pulp stones.2

As DPR is an integral part of dental check-ups, and previous studies have revealed that pulp stones can be detected well on panoramic radiography, as well as on bite-wing and periapical radiography, and in light of the fact that the patient radiation dose is lower for DPR, this study compared DPR and CBCT for pulp stone detection. Patients were not subjected to any additional radiation exposure as part of this study, since data were collected from patients who had both DPR and CBCT records. In a recent study,23 it was reported that DPR showed minimal to no distortion. However, the highest distortion was found in the anterior region. Therefore, in this study, DPR and CBCT images of only the posterior teeth (1,616 molar teeth) were compared in terms of pulp stone detection.

Most previous studies have used conventional radiography or histological examinations to diagnose pulp stones. The prevalence of pulp stones has been found to be higher in histological studies than in conventional radiography studies24 because calcified masses smaller than 200 µm cannot be seen on radiographs.51415 This is probably due to the inherent shortcomings of 2D imaging systems. It is difficult to distinguish such small calcifications from the results of overlapping with other tissues. CBCT is a superior method for detecting pulp stones compared to conventional radiography, as it has greater specificity and accuracy and overcomes the overlapping limitation.13

In conclusion, within the limitations of this study, the presence of pulp stones was not found to be related with sex, the location of the tooth, or the group of teeth, but pulp stones were found more often in teeth with restorations and caries. It can be concluded that chronic pulp irritation might lead to pulp stone formation. This was a cross-sectional study, and there is a need for longitudinal studies with larger samples including radiographic follow-up examinations in order to more precisely characterize the effect of the depth of caries and restorations on pulp stones. DPR, as a 2D imaging system, has inherent limitations that lead to the misinterpretation of pulp stones. CBCT imaging is advised for the examination of pulp stones once there is a suspicion of a pulp stone on DPR.

References

1. Baghdady VS, Ghose LJ, Nahoom HY. Prevalence of pulp stones in a teenage Iraqi group. J Endod. 1988; 14:309–311. PMID: 3251989.

2. da Silva EJNL, Prado MC, Queiroz PM, Nejaim Y, Brasil DM, Groppo FC, et al. Assessing pulp stones by cone-beam computed tomography. Clin Oral Investig. 2017; 21:2327–2333.

3. Sener S, Cobankara FK, Akgünlü F. Calcifications of the pulp chamber: prevalence and implicated factors. Clin Oral Investig. 2009; 13:209–215.

4. Nayak M, Kumar J, Prasad LK. A radiographic correlation between systemic disorders and pulp stones. Indian J Dent Res. 2010; 21:369–373. PMID: 20930347.

5. Goga R, Chandler NP, Oginni AO. Pulp stones: a review. Int Endod J. 2008; 41:457–468. PMID: 18422587.

6. Moody AB, Browne RM, Robinson PP. A comparison of monopolar and bipolar electrical stimuli and thermal stimuli in determining the vitality of human teeth. Arch Oral Biol. 1989; 34:701–705. PMID: 2624561.

7. Horsley SH, Beckstrom B, Clark SJ, Scheetz JP, Khan Z, Farman AG. Prevalence of carotid and pulp calcifications: a correlation using digital panoramic radiographs. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2009; 4:169–173. PMID: 20033616.

8. Movahhedian N, Haghnegahdar A, Owji F. How the prevalence of pulp stone in a population predicts the tisk for kidney stone. Iran Endod J. 2018; 13:246–250. PMID: 29707023.

9. Ravanshad S, Khayat S, Freidonpour N. The prevalence of pulp stones in adult patients of Shiraz Dental School, a radiographic assessment. J Dent (Shiraz). 2015; 16:356–361. PMID: 26636125.

10. Gulsahi A, Cebeci AI, Ozden S. A radiographic assessment of the prevalence of pulp stones in a group of Turkish dental patients. Int Endod J. 2009; 42:735–739. PMID: 19549152.

11. Ranjitkar S, Taylor JA, Townsend GC. A radiographic assessment of the prevalence of pulp stones in Australians. Aust Dent J. 2002; 47:36–40. PMID: 12035956.

12. Patil SR, Ghani HA, Almuhaiza M, Al-Zoubi IA, Anil KN, Misra N, et al. Prevalence of pulp stones in a Saudi Arabian subpopulation: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Saudi Endod J. 2018; 8:93–98.

13. Hsieh CY, Wu YC, Su CC, Chung MP, Huang RY, Ting PY, et al. The prevalence and distribution of radiopaque, calcified pulp stones: a cone-beam computed tomography study in a northern Taiwanese population. J Dent Sci. 2018; 13:138–144.

14. Kannan S, Kannepady SK, Muthu K, Jeevan MB, Thapasum A. Radiographic assessment of the prevalence of pulp stones in Malaysians. J Endod. 2015; 41:333–337. PMID: 25476972.

15. Turkal M, Tan E, Uzgur R, Hamidi MM, Colak H, Uzgur Z. Incidence and distribution of pulp stones found in radiographic dental examination of adult Turkish dental patients. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013; 3:572–576. PMID: 24380011.

16. al-Hadi Hamasha A, Darwazeh A. Prevalence of pulp stones in Jordanian adults. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998; 86:730–732. PMID: 9868733.

17. Arys A, Philippart C, Dourov N. Microradiography and light microscopy of mineralization in the pulp of undemineralized human primary molars. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993; 22:49–53. PMID: 8445542.

18. Tamse A, Kaffe I, Littner MM, Shani R. Statistical evaluation of radiologic survey of pulp stones. J Endod. 1982; 8:455–458. PMID: 6958783.

19. Patel S, Durack C, Abella F, Shemesh H, Roig M, Lemberg K. Cone beam computed tomography in Endodontics - a review. Int Endod J. 2015; 48:3–15. PMID: 24697513.

20. Moss-Salentijn L, Hendricks-Klyvert M. Calcified structures in human dental pulps. J Endod. 1988; 14:184–189. PMID: 3077408.

21. Brullmann D, Schulze RK. Spatial resolution in CBCT machines for dental/maxillofacial applications - what do we know today? Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015; 44:20140204. PMID: 25168812.

22. Shahbazian M, Vandewoude C, Wyatt J, Jacobs R. Comparative assessment of panoramic radiography and CBCT imaging for radiodiagnostics in the posterior maxilla. Clin Oral Investig. 2014; 18:293–300.

23. Kayal RA. Distortion of digital panoramic radiographs used for implant site assessment. J Orthod Sci. 2016; 5:117–120. PMID: 27843885.

24. Bevelander G, Johnson PL. Histogenesis and histochemistry of pulpal calcification. J Dent Res. 1956; 35:714–722. PMID: 13367289.

25. Yaacob HB, Hamid JA. Pulpal calcifications in primary teeth: a light microscope study. J Pedod. 1986; 10:254–264. PMID: 3459852.

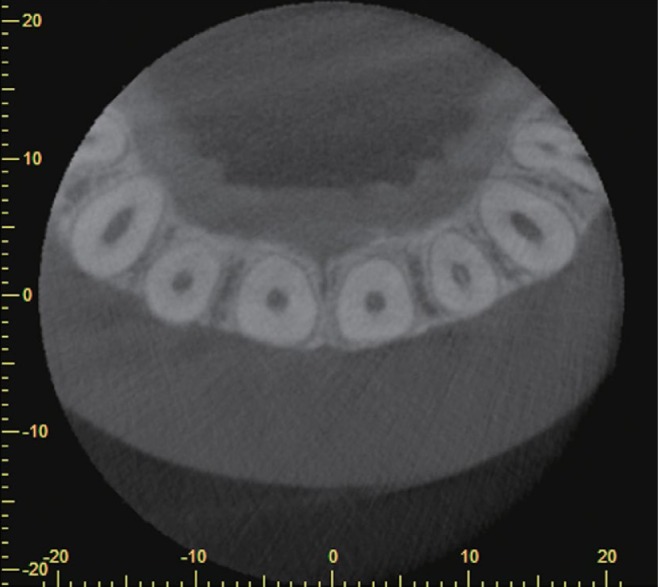

Fig. 2

A pulp stone is found in a left lateral incisor on an axial cone-beam computed tomographic slice.

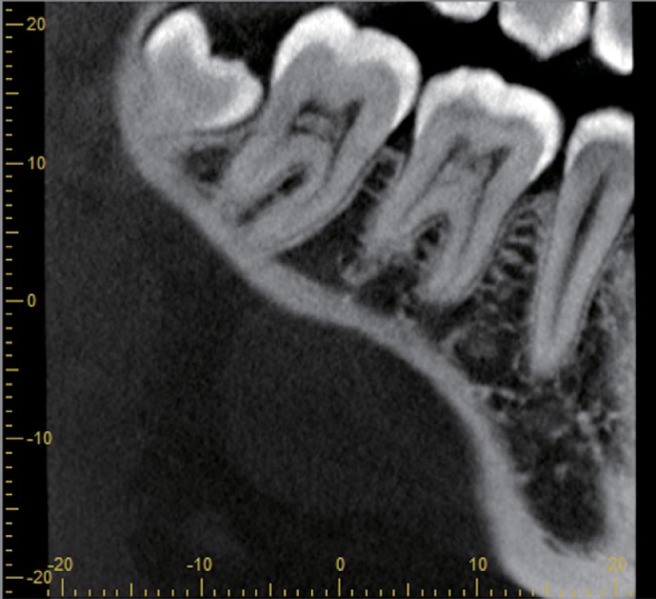

Fig. 4

Pulpal calcifications are found in the lower molars on a coronal cone-beam computed tomographic slice.

Table 1

Number (N) and prevalence (%) of pulp stones according to demographic data and tooth-related variables

Table 2

Associations between the presence or absence of pulp stones and the type of tooth and restoration

Table 3

Associations between the presence or absence of pulp stones and the type of tooth and caries

Table 4

Odds ratios for the presence of pulp stones based on the presence and depth of restorations according to tooth location (maxillary or mandibular arch)

Table 5

Odds ratios for the presence of pulp stones based on the presence and depth of caries according to tooth location (maxillary or mandibular arch)

Table 6

Odds ratios for the presence of pulp stones according to the presence of restorations, caries, and group of teeth

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download