Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to compare the location and the shape of the mandibular lingula in skeletal class I and III patients using panoramic radiography and cone-beam computed tomography.

Materials and Methods

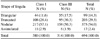

The sample group included 190 skeletal class I patients and 157 class III patients. The location of the lingula in relation to the deepest point of the coronoid notch was classified into 3 types using panoramic radiographs. The shapes of the lingulae were classified into nodular, triangular, truncated, or assimilated types using cone-beam computed tomographic images. The data were analyzed using the chi-square test.

Results

The tips of the lingulae were at the same level as the coronoid notch in 75.3% of skeletal class I patients and above the coronoid notch in 66.6% of class III patients. The positions of the lingulae in relation to the deepest point of the coronoid notch showed statistically significant differences between class I and class III patients. The most common shape was nodular, and the least common was the assimilated shape. Although this trend was not statistically significant, the triangular shape was more frequently observed in class III patients than in class I patients.

Conclusion

The locations and the shapes of the mandibular lingulae were variable. Most of the lingulae were at the same level as the coronoid notch in skeletal class I patients and above the coronoid notch in skeletal class III patients. The nodular and assimilated-shaped lingulae were the most and the least prevalent, respectively.

The lingula of the mandible is a tongue-shaped bony projection on the medial surface of the mandibular ramus that forms the medial boundary of the mandibular foramen.1 The lingula is a reliable anatomic landmark used to determine the position of the mandibular foramen.2 Due to the close proximity of the lingula to the mandibular foramen and neurovascular bundles, it is used as an important anatomical landmark for maxillofacial surgery and for avoiding nerve injury during inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia.34 If oral and maxillofacial surgeons are unable to identify the lingula correctly, intraoperative complications, such as hemorrhage, unfavorable fracture, and nerve injury, may occur.5

The lingula is an important landmark when performing a sagittal split-ramus osteotomy.6 During a sagittal split-ramus osteotomy, the horizontal cut on the medial aspect of the mandible is made just above the lingula.7 The lingula is a projection of bone to which the sphenomandibular ligament attaches, and this structure can provide some protection for the inferior alveolar nerve from needles.8 The sphenomandibular ligament has the potential to impede the diffusion of a local anesthetic solution to the inferior alveolar nerve if the needle contacts the bone at the medial lingula or below the apex of the lingula.9 To avoid this, it is recommended that the needle should make contact with the bone slightly above the lingula.1011 Therefore, accurately estimating the position of the lingula is essential during the administration of local anesthetic because the anesthetic solution is deposited into the lingula region of the mandible.11

The location of the mandibular lingula has been found to be variable.101213 This variation implies a certain risk of injuring the inferior alveolar nerve.1415 The most important clinical landmarks used in inferior alveolar nerve block are the coronoid notch and the pterygomandibular raphe.11 Previous studies reported that most of the lingula was positioned at the same level as the coronoid notch.1012 The height of the injection of the inferior alveolar nerve block is first ascertained by placing the thumb in the coronoid notch and positioning the needle parallel to the occlusal plane.11 Prognathic mandibles generally have a lingula that is positioned higher than the coronoid notch, making it more difficult for the operator to insert the needle at the correct height.16

Structural variations of the lingula followed by inaccurate localization of the mandibular foramen have been implicated as causative factors of unsuccessful inferior alveolar nerve block anaesthesia.17181920 Determining the shape of the lingula is important for surgeons to identify its location more easily during ramus surgery.15 Variations in the shape of the lingula have been reported in previous studies.11521 Tuli et al. examined dry adult mandibles of Indian origin and first described the various morphological shapes of the lingula as triangular, truncated, nodular, and assimilated.1 It is necessary to determine the morphology of the lingula to preserve important structures during surgical procedures involving the mandible near the lingula region.615

It may be beneficial to locate the lingula on panoramic radiographs when performing inferior alveolar nerve block.14,22 The shape of the lingula can be evaluated using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT).2,21 The aim of this study was to determine the location and the shape of the mandibular lingula in skeletal class I and III patients using panoramic radiography and CBCT images.

The protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Dental Hospital. The subjects of this retrospective study were randomly selected from patients who visited Pusan National University Dental Hospital and underwent panoramic radiography and CBCT scans between 2011 and 2016. Patients with pathologic lesions in the posterior mandible and who were missing mandibular molars were excluded from the study. Patients under 18 years of age were excluded due to incomplete development of the mandible. The final sample included data from 190 skeletal class I and 157 class III patients (181 males and 166 females; mean age, 27.0±7.3 years; range, 19–50 years).

All panoramic radiographs were taken using a Proline XC machine (Planmeca Co., Helsinki, Finland). CBCT scans were performed using a PaX-Zenith 3D system (VATECH Co., Hwaseong, Korea) with 5.2–5.7 mA, 106–110 kV, a 24-s exposure time, a voxel size of 0.2–0.4 mm, and a field of view of 16×14 cm or 19×24 cm. The CBCT data were saved in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format, and the images were analyzed using Ez3D Plus Professional CBCT software (VATECK Co., Hwaseong, Korea).

On the panoramic radiographs, the location of the lingula was evaluated relative to the plane parallel to the occlusal plane, passing through the deepest point of the coronoid notch. The locations of the tip of the lingula were classified as follows: type I, the tip of the lingula was above the deepest point of the coronoid notch; type II, the tip of the lingula was at the same level as the deepest point of the coronoid notch; and type III, the tip of the lingula was below the deepest point of the coronoid notch (Fig. 1).

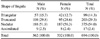

The shapes of the lingulae were classified into 4 types using CBCT images: triangular, truncated, nodular, and assimilated, as previously described by Tuli et al.1 A triangular lingula had a wide base and a narrow rounded or pointed apex, whereas a truncated lingula had a quadrangular top. A nodular lingula was of nodular shape and of variable size, and almost the entire lingula of this type, except for its apex, merged into the ramus. An assimilated lingula was completely incorporated into the ramus (Fig. 2).

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to detect statistically significant differences between the right and the left sides. The chi-square test was used to evaluate differences in the locations and the shapes of the lingulae between class I and class III patients. Whether the shapes of the lingulae were the same bilaterally was also analyzed. P values <.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

There was no statistically significant difference between the right and the left sides, and the results of both sides were averaged. Type II was most frequently observed in skeletal class I patients, and type I was most frequently observed in class III patients. The tip of the lingula was rarely below the coronoid notch. The location of the mandibular lingula in relation to the coronoid notch showed a statistically significant difference between skeletal class I and class III patients (P<.05) (Table 1).

The most common shape was nodular (54.0%) followed by the truncated (29.3%), triangular (14.3%), and assimilated shapes (2.4%). The triangular shape was more frequently observed in class III patients than in class I patients, although there was no statistically significant difference between class I and class III patients (P=.086) (Table 2). The bilateral shape (68.3%) was observed more often than the unilateral shape (31.7%). The bilateral type was more prevalent in class I patients than in class III patients (Table 3).

The tip of the lingula was above the coronoid notch in 62.6% of the triangular-shaped lingulae. The location of the mandibular lingula showed a statistically significant difference according to the shape of the mandibular lingula (P<.05) (Table 4). The location and the shape of the lingula showed no statistically significant difference between the sexes (Tables 5 and 6).

In this study, the location of the mandibular lingula was assessed using panoramic radiographs, and the shapes of the lingulae were investigated using CBCT images. It is important to note that the level at which the lingula is found varies among individuals.23 Panoramic radiographs could provide guidance for locating the position of the lingula and the mandibular foramen.142224 Kim et al.10 reported that the tip of the lingula coincided with the level of the deepest point of the coronoid notch in 82.0% of patients. The results of this study showed that the tip of the lingula was at the same level as the coronoid notch in 75.3% of skeletal class I patients and above the coronoid notch in 66.6% of class III patients. Prognathic mandibles generally had a lingula that was positioned higher than the coronoid notch, which is consistent with a previous study.16

The shape of the lingula has been found to vary across populations.1214152125 The distribution and the frequency of the shapes of the lingulae in this study were different from those reported in previous studies. The triangular shape was the most prevalent in the Indian population.126 The triangular shape15 was the easiest to identify, but it was only found in 14.3% of the patients in this study. The triangular shape was more frequently observed in class III patients than in class I patients, although this trend was not statistically significant. The truncated shape was the most prevalent in the Thai population,1415 and this shape was the second most prevalent in this study. The most common shape in this study was the nodular shape, which was also the most prevalent in the Turkish population.221 The assimilated shape was the least prevalent in this study, as well as in most previous studies.114152126 The identification of a lingula with a nodular or an assimilated pattern during maxillofacial surgery is often challenging, and thus accurate anatomical knowledge is imperative to prevent postoperative complications.1

Lingulae with the same bilateral shape have been most commonly observed in most studies.121415 In this study, bilaterally consistent shapes were observed more often than discordant shapes, and bilateral consistency was more prevalent in class I patients than in class III patients. Several studies have reported that the shape of the lingula showed differences between the sexes.126 Tuli et al.1 found that the truncated type was twice as common in males than in females, and that the nodular type was observed somewhat less than twice as often in females as in males. Sekerci and Sisman21 reported that the nodular and assimilated shapes were the most and the least prevalent types, respectively, and that they found no difference related to sex. In this study, there was no statistically significant difference between the sexes.

A relationship has been found between the shape of the lingula and its location in the ramus of the mandible.27 In general, triangular lingulae were located slightly more posterior than nodular lingulae, and it is important to consider this tendency when performing surgical procedures involving the ramus of the mandible.27 In this study, the triangular shape was located higher than other shapes.

In conclusion, the locations and the shapes of the lingulae in relation to the coronoid notch were variable. Most of the lingulae were at the same level as the coronoid notch in skeletal class I patients and above the coronoid notch in class III patients. The nodular and assimilated shapes of the lingula were the most and the least prevalent, respectively.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The locations of the tips of mandibular lingulae relative to the deepest point of the coronoid notch are classified into 3 types, as shown on panoramic radiography. Black arrow, the tip of the lingula; white arrow, the deepest point of the coronoid notch. A. Type I: the tip of the lingula is above the deepest point of the coronoid notch. B. Type II: the tip of the lingula is at the same level as the deepest point of the coronoid notch. C. Type III: the tip of the lingula is below the deepest point of the coronoid notch.

Fig. 2

The shapes of the lingulae are classified into 4 types on CBCT images: triangular, truncated, nodular, and assimilated. A. The triangular lingula has a wide base and a narrow rounded or pointed apex. B. The truncated lingula has a quadrangular top. C. The nodular lingula is of nodular shape and of variable size, and almost the entire lingula of this type, except for its apex, merges into the ramus. D. The assimilated lingula is completely incorporated into the ramus.

References

1. Tuli A, Choudhry R, Choudhry S, Raheja S, Agarwal S. Variation in shape of the lingula in the adult human mandible. J Anat. 2000; 197:313–317.

2. Senel B, Ozkan A, Altug HA. Morphological evaluation of the mandibular lingula using cone-beam computed tomography. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2015; 74:497–502.

3. Monnazzi MS, Passeri LA, Gabrielli MF, Bolini PD, de Carvalho WR, da Costa Machado H. Anatomic study of the mandibular foramen, lingula and antilingula in dry mandibles, and its statistical relationship between the true lingula and the antilingula. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 41:74–78.

4. Fernandes AC, Cardoso PM, Fernandes IS, de Moraes M. Anatomic study for the horizontal cut of the sagittal split ramus osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 71:1239–1244.

5. Acebal-Bianco F, Vuylsteke PL, Mommaerts MY, De Clercq CA. Perioperative complications in corrective facial orthopedic surgery: a 5-year retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000; 58:754–760.

6. Tom WK, Martone CH, Mintz SM. A study of mandibular ramus anatomy and its significance to sagittal split osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997; 26:176–178.

7. Cillo JE, Stella JP. Selection of sagittal split ramus osteotomy technique based on skeletal anatomy and planned distal segment movement: current therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005; 63:109–114.

9. Barker BC, Davies PL. The applied anatomy of the pterygomandibular space. Br J Oral Surg. 1972; 10:43–55.

10. Kim MK, Paik KS, Lee SP. A clinical and anatomical study on the mandible for inferior alveolar nerve conductive anesthesia in Korean. Korean J Phys Anthropol. 1995; 8:157–173.

11. Khoury JN, Mihailidis S, Ghabriel M, Townsend G. Applied anatomy of the pterygomandibular space: improving the success of inferior alveolar nerve blocks. Aust Dent J. 2011; 56:112–121.

12. Lee SW, Jeong H, Seo YK, Jeon SK, Kim SY, Jang M, et al. A morphometric study on the mandibular foramen and the lingula in Korean. Korean J Phys Anthropol. 2012; 25:153–166.

13. Fujimura K, Segami N, Kobayashi S. Anatomical study of the complications of intraoral vertico-sagittal ramus osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:384–389.

14. Kositbowornchai S, Siritapetawee M, Damrongrungruang T, Khongkankong W, Chatrchaiwiwatana S, Khamanarong K, et al. Shape of the lingula and its localization by panoramic radiograph versus dry mandibular measurement. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007; 29:689–694.

15. Jansisyanont P, Apinhasmit W, Chompoopong S. Shape, height, and location of the lingula for sagittal ramus osteotomy in Thais. Clin Anat. 2009; 22:787–793.

16. Tengku Shaeran TA, Shaari R, Abdul Rahman S, Alam MK, Muhamad Husin A. Morphometric analysis of prognathic and non-prognathic mandibles in relation to BSSO sites using CBCT. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2017; 7:7–12.

17. Keros J, Kobler P, Baucić I, Cabov T. Foramen mandibulae as an indicator of successful conduction anesthesia. Coll Antropol. 2001; 25:327–331.

18. Nicholson ML. A study of the position of the mandibular foramen in the adult human mandible. Anat Rec. 1985; 212:110–112.

19. Kanno CM, de Oliveira JA, Cannon M, Carvalho AA. The mandibular lingula's position in children as a reference to inferior alveolar nerve block. J Dent Child (Chic). 2005; 72:56–60.

20. Ennes JP, Medeiros RM. Localization of mandibular foramen and clinical implications. Int J Morphol. 2009; 27:1305–1311.

21. Sekerci AE, Sisman Y. Cone-beam computed tomography analysis of the shape, height, and location of the mandibular lingula. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014; 36:155–162.

22. Afsar A, Haas DA, Rossouw PE, Wood RE. Radiographic localization of mandibular anesthesia landmarks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998; 86:234–241.

23. Fernandes AC, Loureiro RP, Oliveira L, de Moraes M. Mandibular foramen location and lingula height in dentate dry mandibles, and its relationship with cephalic index. Int J Morphol. 2015; 33:1038–1044.

24. Kaffe I, Ardekian L, Gelerenter I, Taicher S. Location of the mandibular foramen in panoramic radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994; 78:662–669.

25. Lopes PT, Pereira GA, Santos AM. Morphological analysis of the lingula in dry mandibles of individuals in Southern Brazil. J Morphol Sci. 2010; 27:136–138.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download