For early scientific studies of mummies, as they were performed in Europe starting in the 17th century,

1 the wrappings of the mummies had to be removed. The examination of their dentition remained limited to a visual inspection through the occasionally opened lips. This consequently led to misjudgments, as in the case of Ramses II. His teeth “

are clean and in an excellent state of preservation: they were only slightly worn”, Smith stated in his description of the mummy unwrapped in 1886.

2 A later radiographic investigation by Harris corrected this statement: “

Ramesses II was in every sense a true dental cripple, suffering from extreme wear of his teeth […],

extreme periodontitis […]

periapical abscess”.

3 The use of radiography for the non-invasive examination of mummies and their dentition then became widely used as a new method of investigation.

45 Nonetheless, Moodie, in the first systematic radiographic analysis of a major collection of mummies,

6 commented that the identification of caries involved “

numerous difficulties, especially the intervention of many different objects producing obscurity of the teeth.”.

7 The issue of superposition in planar X-ray imaging was only solved with the introduction of X-ray computed tomography (CT). This imaging modality, with its multiple post-processing capabilities, is considered somewhat of a gold standard in mummy research,

8 and CT scans do indeed allow a detailed examination of dental pathologies.

9 The possibilities and indications for conventional radiography, however, should not be overlooked.

10 Under field conditions outside of the clinical setting, the chemical processing and development of analog X-ray films are especially difficult. The use of Polaroid film for such purposes remained an experiment.

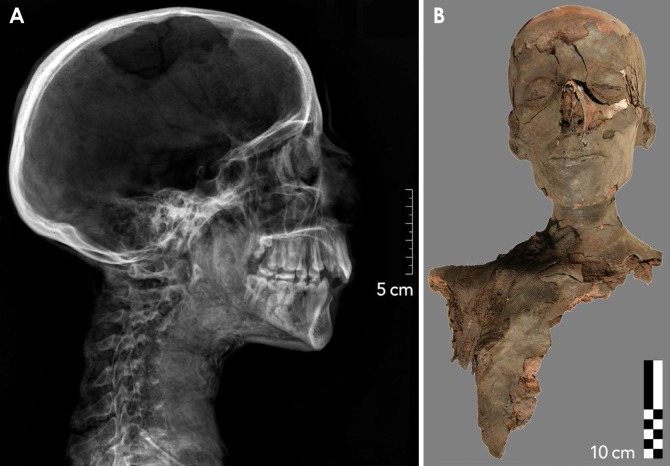

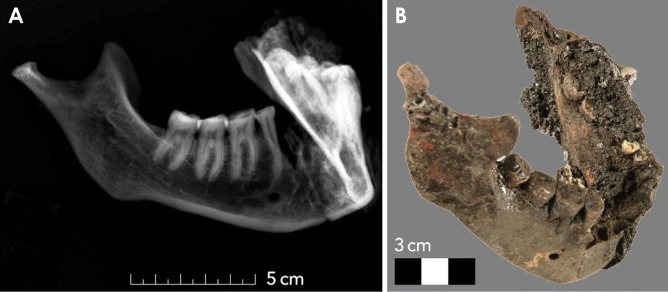

11 In this setting, digital conventional X-ray systems offer significant advantages. However, in any form of conventional radiography, the 3-dimensional structures of the skull base and the dentition are projected onto a 2-dimensional image. The resulting superposition of multiple structures on radiographs is known as anatomical noise.

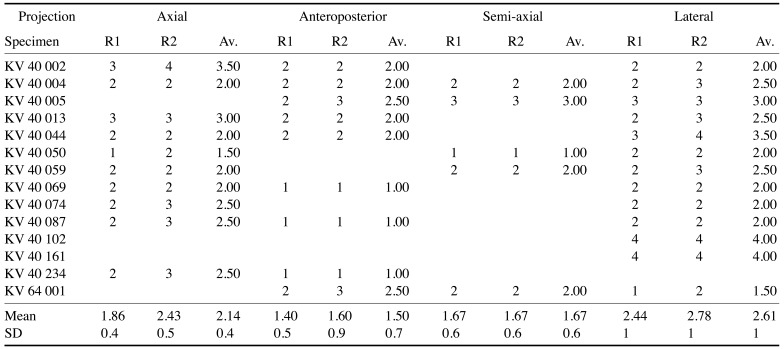

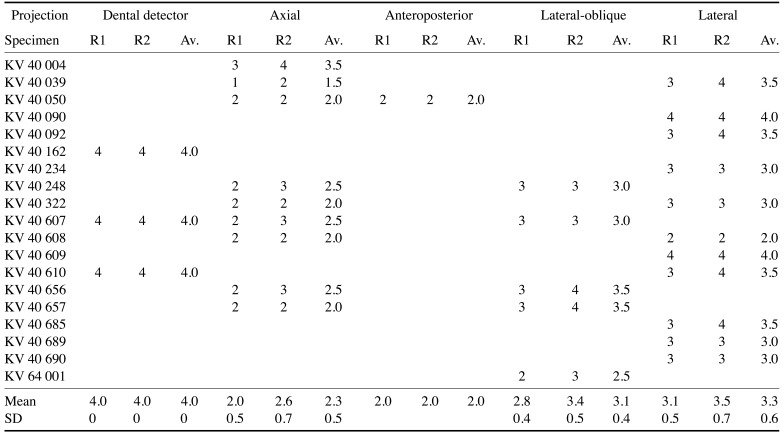

12 Different types of projections can be used to avoid or at least to minimize such superposition artifacts, but they require proper positioning of the head.

13 When wrapped mummies are examined, especially within their coffins, the orientation of the head may be inconvenient, and compensatory adjustment of the incident angle of the X-ray beam is often limited by the thickness of the coffin walls and the position of the mummy. Furthermore, positioning of the detector plate and the X-ray source can become challenging when space in storage depots is limited. In many cases, superposition of anatomical structures therefore cannot be completely avoided and even the tube-shift technique remains of limited use.

13 As a consequence, the interpretation of pathological changes of the dentition or the skeletal system in conventional radiographs of wrapped mummies remains challenging, and even the determination of laterality–that is, distinguishing between the left and right side of the dentition–is not always straightforward. CT scans allowing for later 2-dimensional multiplanar and curved multiplanar reformatting, as well as 3-dimensional volume rendering, can remedy such difficulties.

14 However, for this purpose the specimens need to be transported to a facility where a CT scanner is located, at the risk of damaging fragile specimens and generating substantial costs.

15 Portable digital X-ray equipment, in contrast, can be used on site and has proven its robustness under harsh conditions–heat, cold, dust, etc.–where the chemical processing of conventional X-ray film would be difficult and time-consuming.

16 Furthermore, digital X-ray detector plates provide an excellent spatial resolution perfectly suited for the examination of oral and maxillofacial structures.

17 Another advantage of digital X-ray systems is the almost immediate availability of images. This is especially useful under the above-discussed conditions, where it is often necessary to repeat a shot. An unknown position of the head within a coffin, amulets and jewelry obscuring an area of interest, superposition of anatomical structures, and the unknown densities of coffin walls, cartonnages, and their painted surfaces sometimes require repeated adjustments of imaging parameters (voltage and tube current). This can only be accomplished with a system that performs with minimal time consumption and cost.

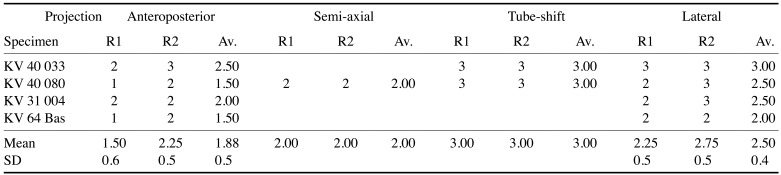

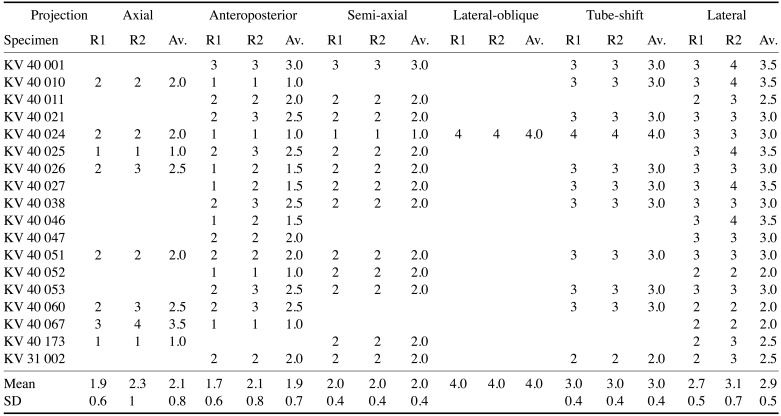

In this article, the advantages and limitations of different approaches and projections are discussed for planar oral and maxillofacial radiography using portable digital X-ray equipment during archaeological excavations. Furthermore, based on our own experiences supporting anthropological investigations in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, recommendations are provided regarding projections and sample positioning for examining the dentition of dry skulls and mummies.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download