1. Pauwels RA, Rabe KF. Burden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Lancet. 2004; 364:613–620.

2. Yoo KH, Kim YS, Sheen SS, Park JH, Hwang YI, Kim SH, Yoon HI, Lim SC, Park JY, Park SJ, Seo KH, Kim KU, Oh YM, Lee NY, Kim JS, Oh KW, Kim YT, Park IW, Lee SD, Kim SK, Kim YK, Han SK. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008. Respirology. 2011; 16:659–665.

3. Yoon HK, Park YB, Rhee CK, Lee JH, Oh YM. Committee of the Korean COPD Guideline 2014. Summary of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical practice guideline revised in 2014 by the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2017; 80:230–240.

4. Korea Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. COPD clinical practice guidelines revised in 2018 [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease;2018. cited 2018 Sep 1. Available from:

http://www.lungkorea.org/bbs/?code=guide.

5. Woodruff PG, Barr RG, Bleecker E, Christenson SA, Couper D, Curtis JL, Gouskova NA, Hansel NN, Hoffman EA, Kanner RE, Kleerup E, Lazarus SC, Martinez FJ, Paine R 3rd, Rennard S, Tashkin DP, Han MK. SPIROMICS Research Group. Clinical significance of symptoms in smokers with preserved pulmonary function. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:1811–1821.

6. Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, Katz PP, Sanchez G, Iribarren C, Omachi TA. Influence of anxiety on health outcomes in COPD. Thorax. 2010; 65:229–234.

7. Wagner PD. Possible mechanisms underlying the development of cachexia in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31:492–501.

8. Schunemann HJ, Dorn J, Grant BJ, Winkelstein W Jr, Trevisan M. Pulmonary function is a long-term predictor of mortality in the general population: 29-year follow-up of the Buffalo Health Study. Chest. 2000; 118:656–664.

9. Chung KS, Jung JY, Park MS, Kim YS, Kim SK, Chang J, Song JH. Cut-off value of FEV1/FEV6 as a surrogate for FEV1/FVC for detecting airway obstruction in a Korean population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016; 11:1957–1963.

10. Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, Oga T. Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest. 2002; 121:1434–1440.

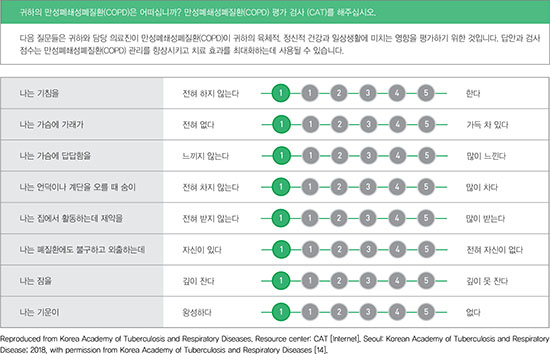

12. Lee S, Lee JS, Song JW, Choi CM, Shim TS, Kim TB, Cho YS, Moon HB, Lee SD, Oh YM. Validation of the Korean version of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test (CAT) and dyspnea-12 questionnaire. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2010; 69:171–176.

13. Lee SD, Huang MS, Kang J, Lin CH, Park MJ, Oh YM, Kwon N, Jones PW, Sajkov D. Investigators of the Predictive Ability of CAT in Acute Exacerbations of COPD (PACE) Study. The COPD assessment test (CAT) assists prediction of COPD exacerbations in high-risk patients. Respir Med. 2014; 108:600–608.

14. Korea Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. Resource center: CAT [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease;2018. cited 2018 Sep 8. Available from:

http://www.lungkorea.org/calculator/?code=cat.

15. Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation: the St. George's respiratory questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992; 145:1321–1327.

16. Burge S, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: definitions and classifications. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003; 41:46s–53s.

17. Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Mullerova H, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Macnee W, Calverley P, Rennard S, Wouters EF, Wedzicha JA. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:1128–1138.

18. Kim MH, Lee K, Kim KU, Park HK, Jeon DS, Kim YS, Lee MK, Park SK. Risk factors associated with frequent hospital readmissions for exacerbation of COPD. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2010; 69:243–249.

19. Joo H, Park J, Lee SD, Oh YM. Comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Koreans: a population-based study. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27:901–906.

20. Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holguin F. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008; 32:962–969.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download