Dear Editor,

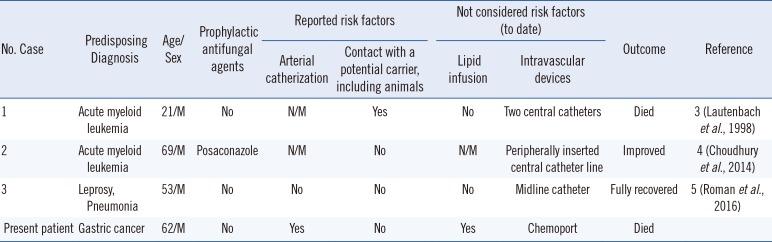

Malassezia yeast species are normal microbiota in the skin of humans and various animals and are mainly lipophilic. Unlike other Malassezia species, M. pachydermatis is non-lipid-dependent; it is a zoonophilic yeast that has been associated with otitis externa and seborrheic dermatitis in dogs [1]. Reported Malassezia species infections have mainly involved M. furfur, and most were localized skin infections [12]. Systemic infection by M. pachydermatis in adults is extremely rare, with only three cases being reported so far (Table 1) [345]. We report a case of M. pachydermatis fungemia in an adult. The Institutional Review Board of Chonbuk National University Hospital exempted this study (IRB No. CUH 2014-08-002).

A 62-year-old male presented to the emergency room of Chonbuk National University Hospital in May 2014 with abdominal pain. He had undergone radical total gastrectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy for poorly differentiated (stage IIIa, T2bN2M0) tubular adenocarcinoma a month previously. On arrival, he was diagnosed as having ileus and an intraabdominal abscess. On hospital day 32, his white blood cell count and C-reactive protein level increased to 1.6×109/L and 1,122.1 nmol/L, respectively, and his body temperature was 37℃. Two sets of venous blood cultures (FA Plus, FN Plus, BacT/Alert 3D system, bioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA) were conducted. Following three days of incubation, very tiny, dry-looking, creamy colonies that broke easily were observed on 5% sheep blood agar and Sabouraud dextrose agar. These colonies were identified as M. pachydermatis using Vitek 2 (bioMérieux, Hazelwood, MO, USA) and VITEK MS (bioMérieux, Marcy L'Etoile, France). Internal transcribed spacer ribosomal RNA sequencing demonstrated 100% identity with GenBank entry NR 126114. A total of four sets (FA Plus, FN Plus) of blood culture—two sets of venous blood culture and two sets of blood culture—were conducted, and all sets gave positive results. The differential time to positivity (DTP) for the chemoport and peripheral venous blood was six hours and five hours, respectively. The patient was treated with a lipid infusion one day after admission, and colony growth was enhanced with olive oil. Antifungal susceptibility results using ETEST (bioMérieux, Marcy L'Etoile, France) demonstrated that the minimal inhibitory concentrations of fluconazole, 5-flucytosine, and voriconazole were 32 µg/mL, >32 µg/mL, and 0.25 µg/mL, respectively [6].

The source of M. pachydermatis infection in this case is unclear, as the patient, his family, and the medical team confirmed that the patient had no contact with dogs. As most M. pachydermatis systemic infections are reported in neonates, risk factors have been determined for only pediatric patients [78]. There is no clear consensus concerning risk factors in adults because of the low incidence in adults (only three cases to date; Table 1) [345]. A recent study suggested that a DTP over two hrs in catheter-related candidemia, except for Candida glabrata, is an optimal cut-off [9]. Although the DTP cut-off has not been determined for Malassezia species, in this case, the DTP was over five hours. We therefore hypothesize that this is a case of catheter-related fungemia, as our patient had a chemoport. Although Chang et al. [2] identified various risk factors for Malassezia infections, they did not consider the influence of intravascular devices because their study was conducted in a neonatal intensive care unit. Lipid infusion could also be a risk factor.

Standardized assays to determine the in vitro antifungal susceptibilities of Malassezia species are unavailable; therefore, we carried out antifungal susceptibility tests based on the CLSI method [6]; to date, most of the results have been reported for animal isolates. The three previously reported fungemia cases in adults were treated with amphotericin B; however, no susceptibility test results are available [345]. Although our patient was treated with amphotericin B for two days, he died of multiple organ failure. As there is no study on the DTP cut-off in Malassezia infections, and there is limited information regarding treatment, clinicians should consider an approach similar to the one outlined for C. glabrata in the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases [10].

In conclusion, although information regarding human infections is limited, lipid infusion and intravascular catheters should be considered as risk factors for M. pachydermatis infection in adults. Further studies on the risk factors and antifungal susceptibility tests are needed.

Acknowledgment

This paper was supported by the Fund of Biomedical Research Institute, Chonbuk National University Hospital.

References

1. Prohic A, Jovovic Sadikovic T, Krupalija-Fazlic M, Kuskunovic-Vlahovljak S. Malassezia species in healthy skin and in dermatological conditions. Int J Dermatol. 2016; 55:494–504. PMID: 26710919.

2. Chang HJ, Miller HL, Watkins N, Arduino MJ, Ashford DA, Midgley G, et al. An epidemic of Malassezia pachydermatis in an intensive care nursery associated with colonization of health care workers' pet dogs. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338:706–711. PMID: 9494146.

3. Groshek PM. Malassezia pachydermatis infections. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:270–271.

4. Choudhury S. Malassezia pachydermatis fungaemia in an adult on posaconazole prophylaxis for acute myeloid leukaemia. Pathology. 2014; 46:466–467. PMID: 24977737.

5. Roman J, Bagla P, Ren P, Blanton LS, Berman MA. Malassezia pachydermatis fungemia in an adult with multibacillary leprosy. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2016; 12:1–3. PMID: 27354932.

6. Cafarchia C, Figueredo LA, Iatta R, Colao V, Montagna MT, Otranto D. In vitro evaluation of Malassezia pachydermatis susceptibility to azole compounds using E-test and CLSI microdilution methods. Med Mycol. 2012; 50:795–801. PMID: 22471886.

7. Mickelsen PA, Viano-Paulson MC, Stevens DA, Diaz PS. Clinical and microbiological features of infection with Malassezia pachydermatis in high-risk infants. J Infect Dis. 1988; 157:1163–1168. PMID: 3373021.

8. Gaitanis G, Magiatis P, Hantschke M, Bassukas ID, Velegraki A. The Malassezia genus in skin and systemic diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012; 25:106–141. PMID: 22232373.

9. Park KH, Lee MS, Lee SO, Choi SH, Sung H, Kim MN, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of differential time to positivity for catheter-related candidemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2014; 52:2566–2572. PMID: 24829236.

10. Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, Garbino J, Kullberg BJ, Lortholary O, et al. ESCMID* guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012; 18(Suppl 7):19–37. PMID: 23137135.

Table 1

Cases of Malassezia pachydermatis systemic infection reported in adults to date

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download