Abstract

Background

After calcaneal fracture surgery, a short leg splint and cast are typically applied. However, these restrict joint exercises, which is inconvenient for patients. In addition, there is a risk of complications, such as pressure ulcers or nerve paralysis with a short leg cast. In this study, we evaluated clinical and radiological outcomes of the use of a specially designed calcaneal brace after calcaneal fracture surgery.

Methods

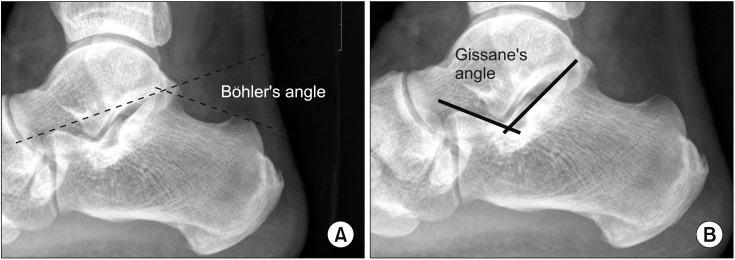

From among patients who underwent open reduction and internal fixation for calcaneal fracture between July 9, 2013 and May 31, 2017, 102 patients who wore a calcaneal fracture brace (group A) and 82 patients who wore a postoperative short leg cast (group B) were randomly chosen for this study. Radiological changes and clinical factors were compared between the two groups. After swelling at the surgical site decreased, a special calcaneal brace was applied to patients in group A. They were allowed to perform early weight bearing and joint motion. Patients in group B were immobilized in a short leg cast and were told to avoid weight bearing for 6 weeks. In each group, the Böhler's angle and Gissane's angle were measured and compared using postoperative and final follow-up radiographs. Pain (measured using a visual analogue scale [VAS]) and ankle joint range of motion (dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, eversion, and inversion) were measured serially until the final follow-up visit.

Results

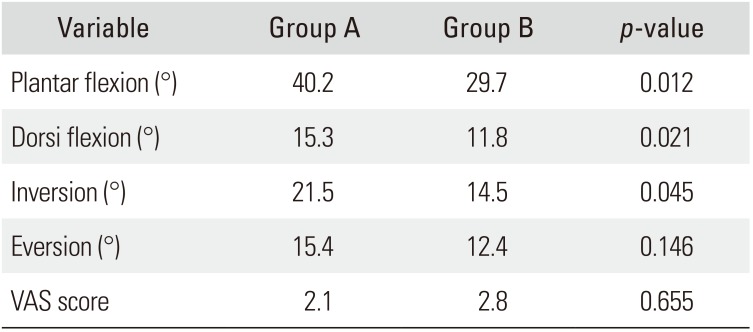

There were no significant differences in the Böhler's angle or Gissane's angle between the two groups as measured postoperatively and at the final follow-up (paired t-test). Differences in the VAS pain score and eversion were also statistically nonsignificant between the two groups. However, group A had a significantly higher range of dorsiflexion (p = 0.021), plantar flexion (p = 0.012), and inversion (p = 0.045) of the ankle than group B (independent t-test).

Conclusions

Application of the calcaneal fracture brace after open reduction and internal fixation of a calcaneal fracture not only maintained the fracture reduction but allowed for greater joint motion than the short leg cast. Thus, the calcaneal fracture brace can be considered an effective postoperative management option that enables early resumption of daily activities and facilitates postoperative joint motion.

Calcaneal fractures are the most common fractures of the tarsal bone. Calcaneal fractures usually occur after an axial load injury such as a high fall or a motor vehicle accident.1) These fractures frequently cause long-term disability and have a severe impact on patients socioeconomically.1) Therefore, various treatment methods have been investigated, developed, and improved by many surgeons. Current treatment options include nonoperative management with or without closed reduction and open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) via various surgical approaches.234567)

After surgery, most patients wear a short leg splint for 2 weeks followed by a short leg non-weight-bearing cast that is worn for 4 weeks. At 6 weeks after surgery, a short leg walking cast is applied and cautious weight bearing is allowed. After 12 weeks, a leather lace-up shoe with a rigid shank can be worn for rehabilitation.8)

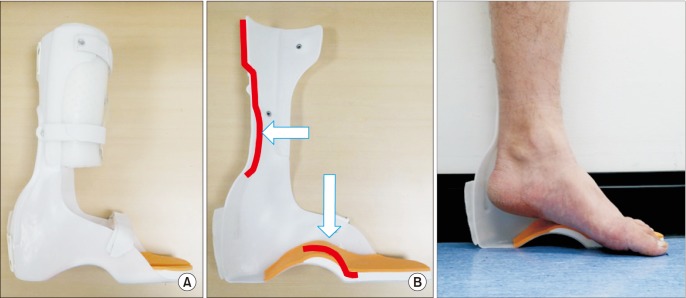

We devised a novel calcaneal brace for patients undergoing ORIF of a calcaneal fracture that reduces the weight on the heel and allows for early weight bearing and increased joint range of motion (ROM). The frame floats approximately 3 cm from the bottom of the calcaneal tuberosity and the angle is fixed at 90°. It is designed to support weight transmitted from the tibia and fibula and is removable from the front pad (Fig. 1). Polypropylene plastic is the main material that holds and supports the calf to the foot. The brace is padded with ethylene vinyl acetate foam sponge from the sole to the shin to provide cushion and with plastic leather in the heel to prevent slipping. It has Velcro straps around the shin and instep to secure the brace to the leg.

In this study, we assessed the radiological and clinical outcomes in patients who wore this brace after calcaneal fracture surgery (Fig. 2). We hypothesized that the calcaneal brace would be helpful for patients who underwent ORIF of a calcaneal fracture.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University Hospital (IRB No. 2017-09-016). All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

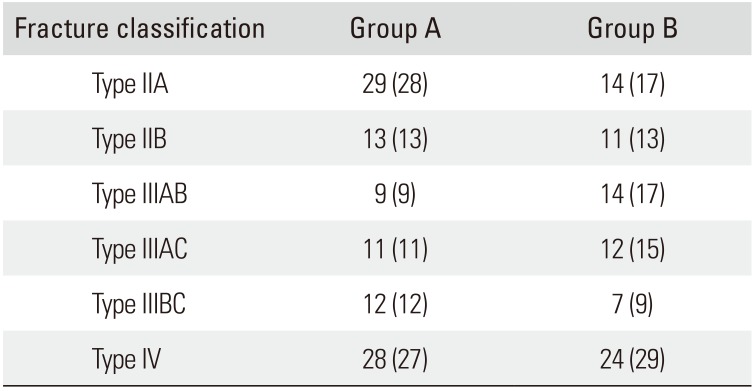

We prospectively recruited 184 consecutive patients with calcaneal fractures that were treated with ORIF from July 2013 to May 2017 at our institute. One hundred two patients (group A) received our specially designed calcaneal brace, which reduces the weight on the heel. There were 68 males and 34 females in group A. Eighty-two patients (group B) received a short leg cast. There were 62 males and 20 females in group B. The average age was 52.4 years (range, 34 to 85 years) in group A and 52.8 years (range, 18 to 88 years) in group B. We sorted calcaneal fractures in each group by Sanders computed tomography classification (Table 1). We excluded patients who had open fractures and subcutaneous infection that precluded use of the calcaneal brace or cast, those who were lost to follow up, and those who could not be rehabilitated because of comorbidities such as brain trauma or spinal trauma. In both groups, the average follow-up period was 14 months (range, 12 to 24 months).

In all patients, surgery was carried out within 2 weeks of injury and after disappearance of swelling. All operations were performed by a single surgeon (CK) using nerve block anesthesia with the patient in lateral recumbency. The incision began approximately 2 cm proximal to the tip of lateral malleolus, just lateral to the Achilles tendon and posterior to the sural nerve and the lateral calcaneal artery, which was extended vertically toward the plantar foot. The horizontal limb was drawn along the junction of the skin of the lateral foot and heel pad. After soft tissue dissection, we confirmed manual reduction using a C-arm intensifier and performed fixation using only Kirschner wires, Steinmann pins and screws.

Postoperatively, the extremity was elevated 10 cm above the level of the heart and observed closely for excessive swelling. A well-padded short leg splint was applied. Between 2 and 3 weeks after surgery, when swelling had subsided sufficiently, group A patients received a specially designed calcaneal brace that allowed for earlier weight bearing and increased joint ROM. Patients in group B received a well-molded short leg cast that was worn until sufficient consolidation was achieved (usually by 6 to 8 weeks), at which point a short leg walking cast was applied and cautious weight bearing was allowed. After 12 weeks, leather lace-up shoes with a rigid shank were worn for rehabilitation.

Bone union was obtained around 7 months after surgery on average. Metal removal was carried out around 8 months after surgery on average.

Clinical outcomes were evaluated at a minimum of 1 year after the operation. Radiological data were collected postoperatively and at the final follow-up. Seven outcome measures were used in this study: Böhler's angle, Gissane's angle, ankle dorsiflexion (°), plantar flexion (°), eversion (°), inversion (°), and visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score.

Standing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were taken for radiological evaluation. On a lateral radiograph of the calcaneus, two important angles are used to determine the quality of reduction after fractures: the tuber angle of Böhler and the crucial angle of Gissane. Böhler's angle, usually between 20° and 40°, is composed of a line drawn from the highest point of the anterior process of the calcaneus to the highest point of the posterior facet and a line drawn tangential to the superior edge of the tuberosity (Fig. 2A). A decrease in this angle indicates that the weight-bearing posterior facet of the calcaneus has collapsed, shifting body weight anteriorly.91011) Gissane's angle is measured directly beneath the lateral process of the talus and bears the axial compressive forces applied by the talus during vertical loading, which is the most common mechanism of injury for calcaneal fractures (Fig. 2B). It is formed by two strong cortical struts extending laterally, one along the lateral margin of the posterior facet and the other extending anteriorly to the beak of the calcaneus.11) We used these two angles to evaluate the radiological outcomes in our study.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank sum test was used to assess differences in clinical parameters after surgery compared to those at the final follow-up. For statistical analysis of radiological data, paired t-tests were used to assess the difference in the postoperative and final follow-up results of each group, and repeated measures independent t-tests were performed to assess the difference in results between the groups. IBM SPSS ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analysis. The alpha level was set at 0.05.

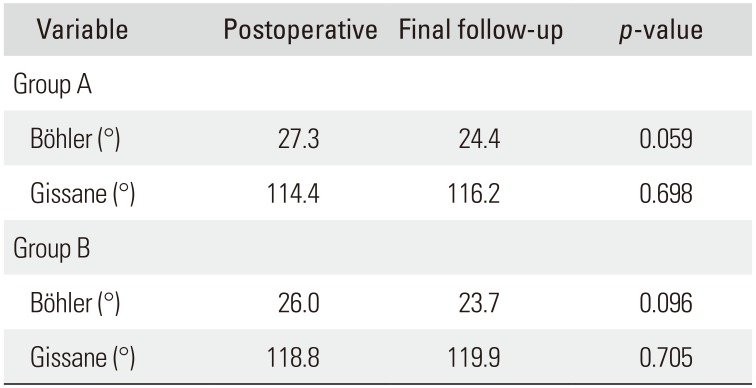

The average postoperative Böhler's and Gissane's angles were 27.3° and 114.4°, respectively, for group A and 26.0° and 118.8°, respectively, for group B. The average final follow-up Böhler's and Gissane's angles were 24.4° and 116.2°, respectively, for group A and 23.7° and 119.9°, respectively, for group B (Table 2). At the final follow-up, the average VAS pain score, ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, eversion, and inversion for group A were 2.1, 15.3°, 40.2°, 15.4°, and 21.5°, respectively; for group B, these measurements were 2.8, 11.8°, 29.7°, 12.4°, and 14.5°, respectively. According to these results, the average postoperative and final follow-up changes in Böhler's and Gissane's angles were not statistically significant (paired t-test). In addition, the average VAS pain score and amount of eversion were not statistically significantly different between groups. However, dorsiflexion (p = 0.021), plantar flexion (p = 0.012), and inversion (p = 0.045) were significantly improved in group A (Table 3). There were no intra- or perioperative complications. No patient sustained neural injury or wound infection.

Calcaneal fractures are challenging to orthopaedic surgeons. Several authors have reported various treatments for calcaneal fractures, and controversy still exists regarding treatment, operative technique, and postoperative management. Treatment options for calcaneal fractures include (1) no reduction with elevation of the foot, a compression dressing, and early ROM training; (2) closed reduction with elevation of the foot, a compression dressing, and early motion; (3) percutaneous reduction techniques such as Essex-Lopresti; (4) ORIF as popularized by Palmer and McReynolds; and (5) primary arthrodesis.111213)

Orthopaedic surgeons generally agree that anatomically reconstructing the calcaneus produces an acceptable functional outcome in most patients with calcaneal fractures. Therefore, we attempted anatomical reduction and fixation of the calcaneus via ORIF and compared the radiological and clinical outcomes of the use of a calcaneal brace with those of a short leg cast.

Gait analysis after calcaneal fracture surgery has demonstrated a functional decline in the toe-off phase due to reduced plantar flexion when transitioning from the stance phase to the swing phase.14) Therefore, one of the primary goals of rehabilitation is to facilitate early postoperative ambulation.

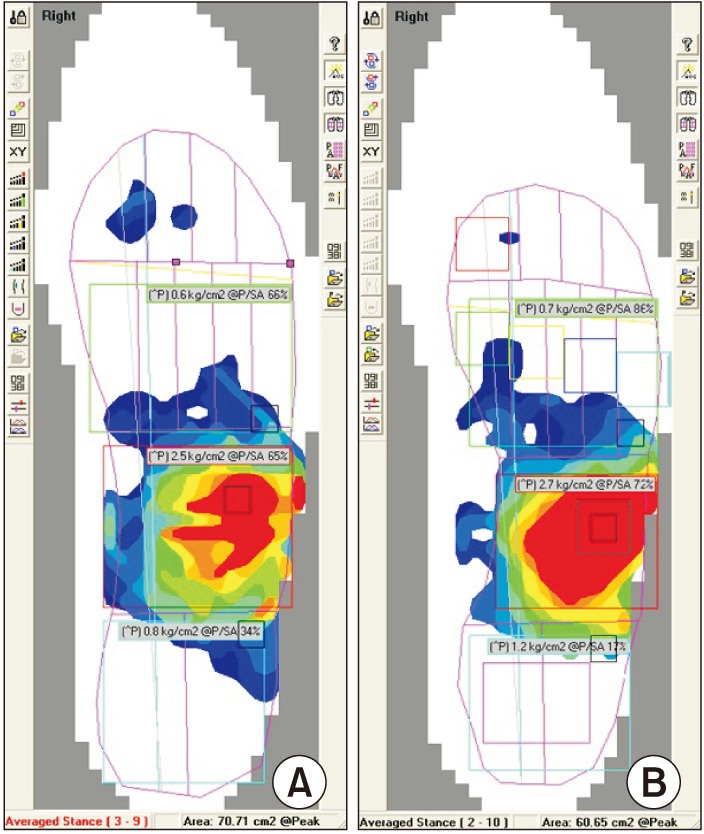

The traditional short leg cast has a long fixation period that can lead to thrombosis, muscle weakness, disuse osteoporosis, pressure ulcers, and nerve palsy.1516) Kienast et al.17) reported that early weight bearing prevents osteoporosis and yields higher American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society scores. Hyer et al.18) reported that early weight bearing in the 4th and 5th weeks after surgery did not shorten the calcaneus, decrease joint reduction, or sacrifice metal fixation. Therefore, our study focused on postoperative therapy, and we designed an innovative calcaneal brace that has a thick pad on the midfoot sole that reduces weight bearing on the heel during standing and walking. The brace allowed for early weight bearing and joint ROM exercise after surgery. Gait analysis using the F-Scan System (ver. 6.34; Tekscan, Boston, MA, USA) showed that the regions of the foot that bore weight were the same for the brace and the short leg cast (Fig. 3).

In our study, ORIF patients who wore our novel calcaneal brace had significantly improved ankle joint angles (except for the eversion) without loss of reduction. These patients were able to bear weight earlier because the heel did not touch the floor directly, which helped to stretch the Achilles tendon during walking and strengthen the joint.

Our study has some limitations. First, among many measurement parameters used to evaluate the outcome of calcaneal fracture repair, we used certain clinical and radiological ones. Second, the sample size was relatively small although inclusion of more cases would probably not have changed the results. Third, more detailed comparison of joint movement recovery is needed. Subtalar joint motion was > 50% of the uninjured foot at the final followup. Nevertheless, our study also has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, although many studies have examined operative techniques and compared operative and nonoperative treatments, few studies have evaluated postoperative care in patients with calcaneal fractures. Our postoperative calcaneal brace appears to have many advantages over traditional methods.

In conclusion, our calcaneal brace reduced pressure on the heel following calcaneal fracture repair, which allowed patients to return to ordinary daily activities earlier and resulted in satisfying outcomes, including improvement in ankle joint ROM. Therefore, our calcaneal brace could be a useful postoperative tool for patients undergoing ORIF of calcaneal fractures.

References

1. Brauer CA, Manns BJ, Ko M, Donaldson C, Buckley R. An economic evaluation of operative compared with nonoperative management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005; 87(12):2741–2749. PMID: 16322625.

2. Buckley R, Tough S, McCormack R, et al. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002; 84(10):1733–1744. PMID: 12377902.

3. Agren PH, Wretenberg P, Sayed-Noor AS. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013; 95(15):1351–1357. PMID: 23925738.

4. Griffin D, Parsons N, Shaw E, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for closed, displaced, intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2014; 349:g4483. PMID: 25059747.

5. Stulik J, Stehlik J, Rysavy M, Wozniak A. Minimally-invasive treatment of intra-articular fractures of the calcaneum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006; 88(12):1634–1641. PMID: 17159178.

6. Bruce J, Sutherland A. Surgical versus conservative interventions for displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; (1):CD008628. PMID: 23440830.

8. Ishikawa SN. Fractures and dislocations of the foot. In : Azar FM, Canale ST, Beaty JH, editors. Campbell's operative orthopaedics. 13ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier;2017. p. 4276–4350.

9. Agren PH, Mukka S, Tullberg T, Wretenberg P, Sayed-Noor AS. Factors affecting long-term treatment results of displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures: a post hoc analysis of a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2014; 28(10):564–568. PMID: 24824095.

10. Paul M, Peter R, Hoffmeyer P. Fractures of the calcaneum: a review of 70 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004; 86(8):1142–1145. PMID: 15568527.

11. Sanders R. Displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000; 82(2):225–250. PMID: 10682732.

12. Paley D, Hall H. Intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: a critical analysis of results and prognostic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993; 75(3):342–354. PMID: 8444912.

13. Raymakers JT, Dekkers GH, Brink PR. Results after operative treatment of intra-articular calcaneal fractures with a minimum follow-up of 2 years. Injury. 1998; 29(8):593–599. PMID: 10209590.

14. Follak N, Merk H. The benefit of gait analysis in functional diagnostics in the rehabilitation of patients after operative treatment of calcaneal fractures. Foot and Ankle Surg. 2003; 9(4):209–214.

15. Halanski M, Noonan KJ. Cast and splint immobilization: complications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008; 16(1):30–40. PMID: 18180390.

16. Micheli LJ. Thromboembolic complications of cast immobilization for injuries of the lower extremities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975; (108):191–195. PMID: 237645.

17. Kienast B, Gille J, Queitsch C, et al. Early weight bearing of calcaneal fractures treated by intraoperative 3D-fluoroscopy and locked-screw plate fixation. Open Orthop J. 2009; 3:69–74. PMID: 19750017.

18. Hyer CF, Atway S, Berlet GC, Lee TH. Early weight bearing of calcaneal fractures fixated with locked plates: a radiographic review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2010; 3(6):320–323. PMID: 20538916.

Fig. 1

A specially designed brace to be worn postoperatively by patients with calcaneal fractures. The brace prevents weight bearing on the fracture site because the heel does not touch the ground. (A) The brace. (B) Wight-bearing areas (arrows). (C) The brace in use.

Fig. 3

Gait analysis using the F-Scan System (ver. 6.34; Tekscan, Boston, MA, USA). The area and region of the foot are the same in (A) and (B). (A) With the specially designed brace. (B) With the short leg cast.

Table 1

Comparison of Calcaneal Fracture Classification with Sanders Computed Tomography Classification in Each Group

| Fracture classification | Group A | Group B |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIA | 29 (28) | 14 (17) |

| Type IIB | 13 (13) | 11 (13) |

| Type IIIAB | 9 (9) | 14 (17) |

| Type IIIAC | 11 (11) | 12 (15) |

| Type IIIBC | 12 (12) | 7 (9) |

| Type IV | 28 (27) | 24 (29) |

Table 2

Comparison of the Böhler's and Gissane's Angles in Each Group

| Variable | Postoperative | Final follow-up | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | |||

| Böhler (°) | 27.3 | 24.4 | 0.059 |

| Gissane (°) | 114.4 | 116.2 | 0.698 |

| Group B | |||

| Böhler (°) | 26.0 | 23.7 | 0.096 |

| Gissane (°) | 118.8 | 119.9 | 0.705 |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download