Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated the effects of lid wiper epitheliopathy on the clinical manifestations of dry eye in patients refractory to conventional medical treatment.

Methods

Forty-six patients (46 eyes) completed the subjective Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), and we obtained objective measures including the tear break-up time (TBUT), the National Eye Institute (NEI) corneal staining score, tear osmolarity, and lid wiper epitheliopathy as revealed on photographs taken using a yellow filter after fluorescein instillation. The images were graded using the Korb B protocol.

Results

The mean OSDI score was 48.06 ± 21.19; 34 patients (73.9%) were had scores ≥33. Lid wiper epitheliopathy was evident in 41 (89.1%), and the epitheliopathy grade and OSDI score were correlated (r = 0.56, p < 0.01). The NEI score was also positively correlated with the OSDI score (r = 0.54, p < 0.01), but the mean value was low (1.59 ± 2.13). The OSDI score did not correlate significantly with either the TBUT or tear osmolarity (r = −0.16, p = 0.279; r = 0.16, p = 0.298, respectively).

Figures and Tables

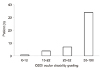

| Figure 1Age distribution. Age of 20-29 (n = 20) (43.5%), age of 30-39 (n = 14) (30.4%), age of 40-49 (n = 5) (10.9%), and age of ≥50 (n = 7) (15.2%). |

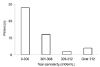

| Figure 2Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) ocular disability grading distribution. Normal (0-12) (n = 1) (2.2%), Mild (13-22) (n = 4) (8.7%), Moderate (23-32) (n = 7) (15.2%), and Severe (≥33) (n = 34) (73.9%). |

| Figure 3Tear osmolarity distribution. Under 300 (n = 28) (60.9%), 301-308 (n = 12) (26.1%), 309-312 (n = 2) (4.3%), and Over 312 (n = 4) (8.7%). |

| Figure 4Lid wiper epitheliopathy grading distribution. 0 (n = 5) (10.9%), 1.0 (n = 1) (2.2%), 1.5 (n = 4) (8.7%), 2.0 (n = 11) (24.0%), 2.5 (n = 5) (10.9%), and 3.0 (n = 20) (43.5%). *By Korb protocol B, 2010. |

| Figure 5Correlation of Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score with other variables. (A) National Eye Institute (NEI) fluorescein staining scale, (B) lid wiper epitheliopathy grading, (C) tear osmolarity, and (D) tear break-up time (TBUT). *Simple linear regression test. |

| Figure 6One representative case with lid wiper epitheliopathy. A patient complained of sustained dry eye symptoms, whose Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score was 56.2. There was no corneal staining under slit lamp examination (A). However, prominent lid wiper epitheliopathy was noted on the upper eyelid (B). |

Notes

This study was supported in part by Alumni of Department of Ophthalmology, Korea University College of Medicine.

References

1. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007; 5:75–92.

2. Ahn JM, Lee SH, Rim TH, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with dry eye: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010-2011. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 158:1205–1214.e7.

3. Barabino S, Labetoulle M, Rolando M, Messmer EM. Understanding symptoms and quality of life in patients with dry eye syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2016; 14:365–376.

4. Baudouin C, Aragona P, Van Setten G, et al. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014; 98:1168–1176.

5. Bartlett JD, Keith MS, Sudharshan L, Snedecor SJ. Associations between signs and symptoms of dry eye disease: a systematic review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015; 9:1719–1730.

6. Nichols KK, Nichols JJ, Mitchell GL. The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea. 2004; 23:762–770.

7. Schulze MM, Srinivasan S, Hickson-Curran SB, et al. Lid wiper epitheliopathy in soft contact lens wearers. Optom Vis Sci. 2016; 93:943–954.

8. Korb DR, Herman JP, Greiner JV, et al. Lid wiper epitheliopathy and dry eye symptoms. Eye Contact Lens. 2005; 31:2–8.

9. Efron N, Brennan NA, Morgan PB, Wilson T. Lid wiper epitheliopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016; 53:140–174.

10. Hyon JY, Kim HM, Lee D, et al. Korean guidelines for the diagnosis and management of dry eye: development and validation of clinical efficacy. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2014; 28:197–206.

11. Ng ALK, Choy BNK, Chan TCY, et al. Comparison of tear osmolarity in rheumatoid arthritis patients with and without secondary Sjogren syndrome. Cornea. 2017; 36:805–809.

12. Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DR, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010; 128:94–101.

13. Yoon KC, Im SK, Kim HG, You IC. Usefulness of double vital staining with 1% fluorescein and 1% lissamine green in patients with dry eye syndrome. Cornea. 2011; 30:972–976.

14. Chun YS, Park IK. Reliability of 4 clinical grading systems for corneal staining. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 157:1097–1102.

15. Korb DR, Herman JP, Blackie CA, et al. Prevalence of lid wiper epitheliopathy in subjects with dry eye signs and symptoms. Cornea. 2010; 29:377–383.

16. Peck T, Olsakovsky L, Aggarwal S. Dry eye syndrome in menopause and perimenopausal age group. J Midlife Health. 2017; 8:51–54.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download