This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

Chronic bronchitis (CB) is an important phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The purpose of this study is to evaluate different pattern of COPD assessment test (CAT) score between CB and non-CB patients.

Methods

Patients were recruited from 45 centers in Korea, as part of the Korean COPD Subgroup Study cohort. CB was defined when sputum continued for at least 3 months.

Results

Total 958 patients with COPD were eligible for analysis. Among enrolled patients, 328 (34.2%) were compatible with CB. The CAT score was significantly higher in patients with CB than non-CB, and each component of CAT score showed a similar result. CB was significantly associated with CAT score when adjusted with age, sex, modified Medical Research Council, and post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second. Each component of CAT score between patients with CB and non-CB showed different pattern according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease grade.

Conclusion

CAT score is significantly higher in patients with CB than non-CB. Each component of CAT score was significantly different between two groups.

Keywords: Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive, Bronchitis, Chronic, Quality of Life

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is irreversible airway disease with recurrent exacerbations and is the cause of significant mortality and morbidity around the globe

1. COPD consists of two different phenotypes including chronic bronchitis (CB) and emphysema. CB has serious clinical outcomes, regarding higher risk of frequent exacerbations

2, higher risk of mortality risk

3, more frequent hospital admission

4, worse quality of life symptom

5, worse mental well-being

5, and accelerated lung function decline

6.

Diagnosis, severity, and treatment of COPD depends on the extent of airflow limitation

1. However, there is no strong correlation between the degree of airflow limitation and health-related quality of life (HRQL)

7. Many disease specific questionnaires have been introduced, including St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). SGRQ is a valid, reliable tool to evaluate HRQL. However, this health status measure are long and less practical for clinical routine use

8. COPD assessment test (CAT) have been developed to avoid these defects. CAT is composed of only eight questions and a key is not needed to calculate a score

9. Moreover, a strong correlation between CAT and SGRQ was shown through two recent large multinational cross sectional studies

1011.

Although it is known that CB is associated with poor qulity of life, data regarding CB and CAT is limited. Moreover, it is whorth analyzing which component of quality of life is affected more in CB patients. Also, little has been known for the pattern of difference in quality of life between CB and non-CB according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) grade. The aim of this study was to evaluate the difference of CAT score and each component of CAT score between CB and non-CB. Additional aim was to discover the tendency of CAT score between two groups could be influenced by GOLD grade.

Materials and Methods

This multicenter, cross-sectional, and retrospective study analyzed data obtained from the Korean COPD Subgroup Study cohort. This cohort was initiated in April 2012 and is currently ongoing. We analyzed 985 patients with COPD who answered whether sputm continued for 3 months. Patients were eligible if they were age ≥40 years and a post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV

1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) of <0.7. All patients were subjected to pulmonary function test. Parameters collected at the time of recruitment included age, sex, smoking history, pulmonary function test results, CAT score, SGRQ score, previous history of exacerbation, frequency of emergency room visits, admission into intensive care unit, presence of endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, duration since COPD diagnosis, duration of COPD treatment, education, area of living, biomass fuel exposure, occupational history, present medication for COPD, comorbidities, previous history of disease, weight, height, 6-minute walking distance, and symptoms (dyspnea, chronic cough, and chronic sputum). CB was defined when sputum continued for at least 3 months. CAT score was measured in stable state, not exacerbated. CAT was measured by the research nurse and result of each component was registered in electronic Case Report Form via web. Each component of CAT score was as follows: CAT 1, cough; CAT 2, phlegm; CAT 3, chest tighitness; CAT 4, breathless; CAT 5, limitation of activity; CAT 6, confidence; CAT 7, sleep; and CAT 8, enegy. Post-bronchodilator values were used, the patients were classified according to GOLD

1 as COPD grade 1 (FEV

1 ≥80% pred), COPD grade 2 (50% pred≤FEV

1≤80% pred), COPD grade 3 (30% pred≤FEV

1≤50% pred), and COPD grade 4 (FEV

1 ≤30% pred). This study was approved by the ethics committees of hospital's individual Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all the study patients.

All data were performed using SPSS statistical package, version 16, for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) or number (%). Categrical values were compared between two groups using chi-square test, and continuous values were compared using t test. Multiple linear regression between the CAT score was performed to correct cofounding factors.

Results

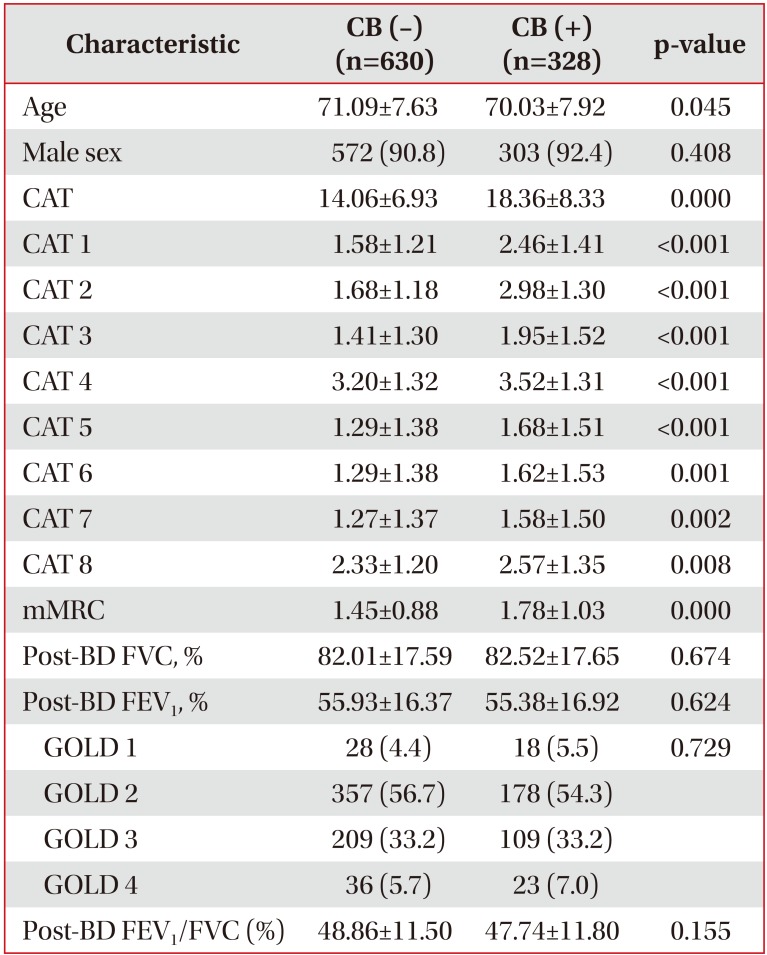

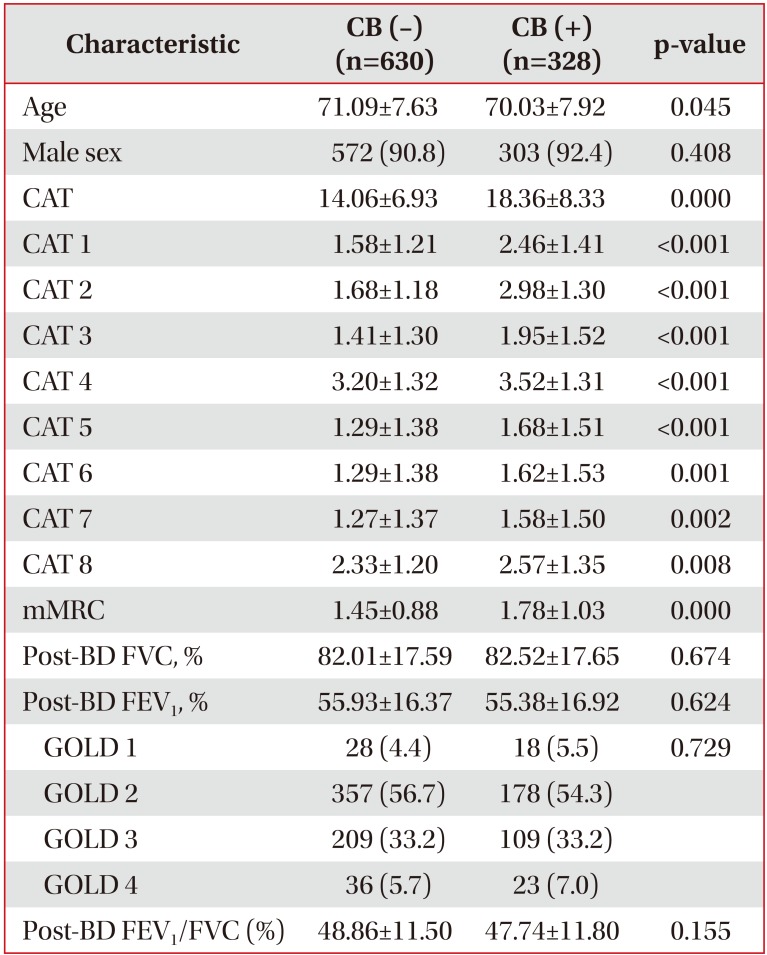

Total 958 patients with COPD were eligible for analysis. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in

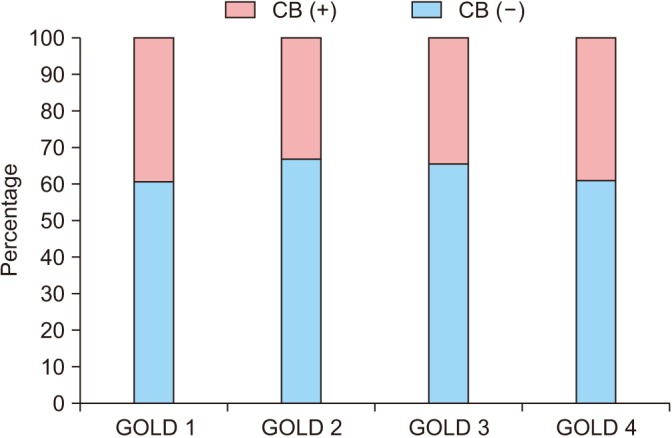

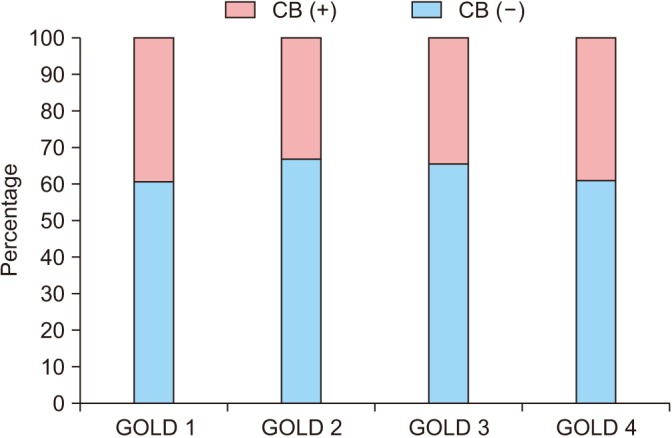

Table 1. Among enrolled patients, 328 (34.2%) were compatible with CB. There was similar distribution of CB according to GOLD grade (

Figure 1). There was significant, however, small difference in age between CB and non-CB groups. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) score was significantly higher in patients with CB than non-CB. There was no stastically significant difference in post-bronchodilator FVC, FEV

1, and FEV

1/FVC between two groups.

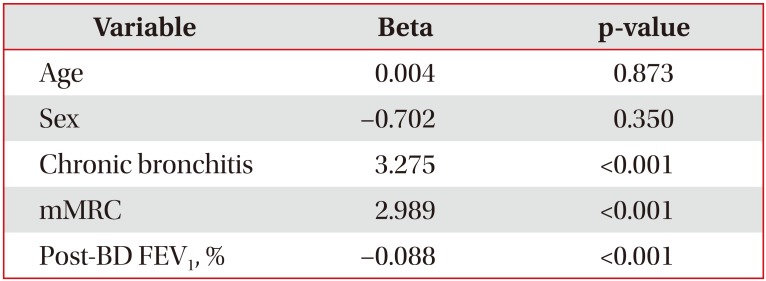

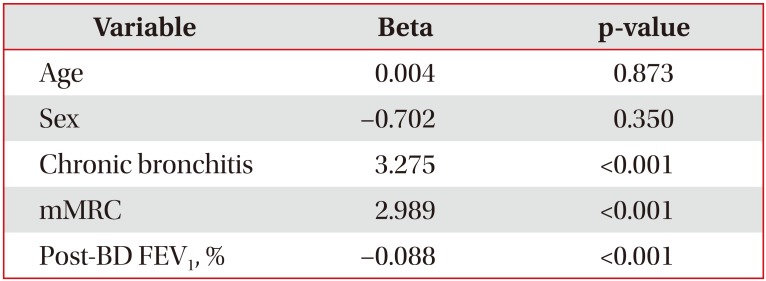

The CAT score was significantly higher in patients with CB than non-CB. Each component of CAT score was significantly different between two groups. Question 2 showed highest gap (differences 1.32), while question 8 showed lowest gap (differences 0.24). CB was significantly associated with CAT score when adjusted with age, sex, mMRC, and post-bronchodilator FEV

1 (%) in multiple linear regression analysis (

Table 2).

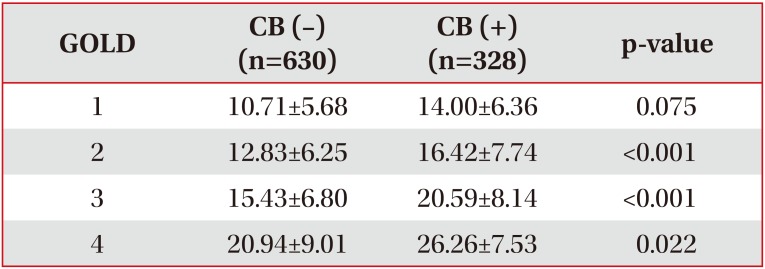

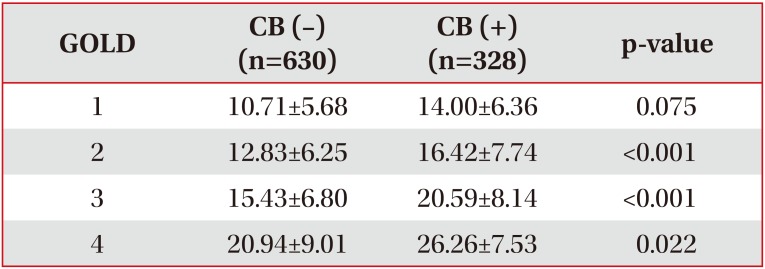

The CAT score classified according to GOLD grade showed a similar trend between two groups. CAT score differed significantly in GOLD grade 2, grade 3, and grade 4 (

Table 3). However, interestingly, each component of CAT score between patients with CB and non-CB showed different pattern according to GOLD grade (

Figure 2).

Discussion

The pathogenesis of CB is excessive mucus in airway, leading to airway limitation. Hypersecretion of mucus provoke airway obstruction

12, changes surface tension of airway

13, aggravating airway collapse. Several studies showed CB is related with poor clinical consequences, including HRQL

7. We used CAT score to evaluate HRQL because CAT score is simple and has outstanding measurement property

91011. In present study, patients with CB had higher value of CAT score and each component than non-CB, suggesting patients with CB had worse quality of life.

It is interesting that not only score for questions 1 and 2 (which is question for cough and phlegm) but also other score was also significantly higher in CB group. CB was defined by phlegm in this study. Thus, it is understandable that score 1 and 2 are higher in CB patients. However, not only cough and phlegm but also other components of quality of life differed significantly. This difference was even significant after adjustment of age, sex, mMRC, and post-bronchodilator FEV1 (%). This result suggests that simply cough and sputum are not the whole drivers to decrease quality of life in CB patietns.

This tendency was statistically significant even if patients were classified to GOLD grade. However, patten of CAT between CB abd non-CB groups was influenced by GOLD grade. This pattern was less prominent in GOLD 1 and most prominent in GOLD 3.

Previous studies focused on the relationship between CAT score and other factors. Pothirat et al.

14 showed change in CAT score was valid to detect acute exacerbation. Yoshimoto et al.

15 suggested CAT score was related with airflow limitation. Sarioglu et al.

16 demonstrated CAT score was associated with systemic inflammatory marker. In this study, we analyzed the relationship between CAT score and presence of CB. Our finding that patients with CB had worse quality of life symptom than non-CB was consistent with former study, although measurement was different between two studies (CAT vs. SGRQ)

5.

Our study is valuve in that we showed CB can be an independent factor associated with poor quality of life. Previous studies simply showed that CAT is higher in CB patients. However, in this study, we performed multiple linear regression and CB was significantly associated with CAT score even adjusted with other confounding factors. Moreover, to our best knowledge, this is the first report that showed differnet patterns of CAT between CB/non-CB according to GOLD grage. Interestingly, it seemed that CB was more profoundly affect quality of life in GOLD 3 patients than GOLD 1.

In daily clinical practice, CB is very common and can be easily identified by simple questionnaire. However, many physicians often overlooked the importance of CB in practice. The result of our study can be very good evidence that CB patients are suffered by poor quality of life. Thus, physicians should try to find CB phenotype more actively and check each component of quality of life. Aggressive intervention to improve each component of CAT score is mandatory.

Our study has some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional, not a longitudinal follow-up study. Second, the definition of CB is not a classic one

17. We defined CB as patients with sputum more than 3 months

18. The reason why we utilized this definition is question for CB is not familiar with Koreans. The question, especially, “two consecutive years” can not be adquetly translated into Koreans. Because of the language problem, the answer rate for “two consecutive years” qucestions was very low in our database. It was also evident in a study of Choi et al.

17. Unlike previous Western report where prevalence of CB is around 30%, only 11.5% of Korean COPD patients were classified as CB by classic definition. Thus, we modified CB questions in simple way that old Koreans can easily understand the meaning of question.

We identified patients with CB had worse quality of life than non-CB by using CAT score. Quality of life in patients was confluence by GOLD grade. Each component of CAT score was significantly different between two groups. This difference was most prominent in GOLD 3 patients and least in GOLD 1.

Figure 1

Percentage of chronic bronchitis (CB) according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) grade.

Figure 2

Different patterns of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test (CAT) score between chronic bronchitis (CB) and non-CB patients according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) grade (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

Table 1

Baseline characteristics

|

Characteristic |

CB (–) (n=630) |

CB (+) (n=328) |

p-value |

|

Age |

71.09±7.63 |

70.03±7.92 |

0.045 |

|

Male sex |

572 (90.8) |

303 (92.4) |

0.408 |

|

CAT |

14.06±6.93 |

18.36±8.33 |

0.000 |

|

CAT 1 |

1.58±1.21 |

2.46±1.41 |

<0.001 |

|

CAT 2 |

1.68±1.18 |

2.98±1.30 |

<0.001 |

|

CAT 3 |

1.41±1.30 |

1.95±1.52 |

<0.001 |

|

CAT 4 |

3.20±1.32 |

3.52±1.31 |

<0.001 |

|

CAT 5 |

1.29±1.38 |

1.68±1.51 |

<0.001 |

|

CAT 6 |

1.29±1.38 |

1.62±1.53 |

0.001 |

|

CAT 7 |

1.27±1.37 |

1.58±1.50 |

0.002 |

|

CAT 8 |

2.33±1.20 |

2.57±1.35 |

0.008 |

|

mMRC |

1.45±0.88 |

1.78±1.03 |

0.000 |

|

Post-BD FVC, % |

82.01±17.59 |

82.52±17.65 |

0.674 |

|

Post-BD FEV1, % |

55.93±16.37 |

55.38±16.92 |

0.624 |

|

GOLD 1 |

28 (4.4) |

18 (5.5) |

0.729 |

|

GOLD 2 |

357 (56.7) |

178 (54.3) |

|

|

GOLD 3 |

209 (33.2) |

109 (33.2) |

|

|

GOLD 4 |

36 (5.7) |

23 (7.0) |

|

|

Post-BD FEV1/FVC (%) |

48.86±11.50 |

47.74±11.80 |

0.155 |

Table 2

Multiple linear regression analysis for factors affecting CAT score

|

Variable |

Beta |

p-value |

|

Age |

0.004 |

0.873 |

|

Sex |

−0.702 |

0.350 |

|

Chronic bronchitis |

3.275 |

<0.001 |

|

mMRC |

2.989 |

<0.001 |

|

Post-BD FEV1, % |

−0.088 |

<0.001 |

Table 3

CAT score according to GOLD grade

|

GOLD |

CB (–) (n=630) |

CB (+) (n=328) |

p-value |

|

1 |

10.71±5.68 |

14.00±6.36 |

0.075 |

|

2 |

12.83±6.25 |

16.42±7.74 |

<0.001 |

|

3 |

15.43±6.80 |

20.59±8.14 |

<0.001 |

|

4 |

20.94±9.01 |

26.26±7.53 |

0.022 |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download