INTRODUCTION

Assessment of diastolic function has been accepted as an important routine clinical practice, and Doppler echocardiography remains a main clinical tool.

1) Although clinical guidelines or recommendations are available for standard classification of diastolic dysfunction, the classification of diastolic stages continues to vary between observers, because conflicting findings are common and many patients fall “between” stages.

2) The most frequently observed and important pattern would be the combination of relaxation abnormality and possibly high left ventricular filling pressure (hLVFP), characterized by E/A ratio <1.0 and high E/e'.

3)4) These patients show characteristic Doppler findings and have a prognosis similar to that of the pseudonormal group, but significantly worse compared with that of the impaired relaxation group.

3) The prevalence of patients with both impaired relaxation and hLVFP in different patient populations is low, suggesting the relatively diminished clinical importance of the “new grade.”

5) Further investigations to characterize the clinical features of patients with “new grade” are required for clinical introduction. Specifically, it should be determined whether these patients with both impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP have the same hemodynamic impact.

One practical approach is application of the diastolic stress test to observe hemodynamic changes during exercise, which would be more clinically important and relevant. Low-level supine bicycle exercise combined with simultaneous Doppler echocardiographic measurements are very effective for estimating left ventricular filling pressure (LVFP) and the peak systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) during exercise.

6)7)8) Exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension (EiPH) documented during the diastolic stress test has important prognostic implications for various clinical conditions.

9)10) Thus, we sought to evaluate the clinical usefulness of diastolic stress echocardiography (DSE) during low-level supine exercise in patients with both impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP and to assess clinical variables associated with characteristic hemodynamic changes, including development of hLVP or EiPH in this select group of patients.

RESULTS

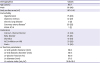

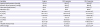

After exclusion of inadequate Doppler tracing from 31 patients, finally a total of 120 patients with clear Doppler tracings at rest and during exercise was analyzed: their mean age was 65±7 years and 58 patients (48%) were men (

Table 1). All patients showed normal LV size and contractility. Most patients complained of minimal or mild dyspnea, and, in one patients, dyspnea was categorized as New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III. Before diastolic stress test, 23 patients underwent pulmonary function test and only 7 patients showed mild obstructive disease and no patient had a history of regular medication for chronic lung disease or abnormal lung infiltration on chest X-ray.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of participants

|

Demographics |

Values |

|

Age (years) |

65±7 |

|

Male |

58 (48) |

|

Body surface area (m2) |

1.67±0.16 |

|

Comorbidity |

|

|

Hypertension |

75 (63) |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

32 (27) |

|

Chronic lung disease |

2 (2) |

|

Coronary artery disease*

|

26 (22) |

|

NYHA FC III |

1 (1) |

|

Medication |

|

|

Calcium channel blocker |

41 (34) |

|

Beta-blocker |

25 (21) |

|

Diuretics |

12 (10) |

|

ACE inhibitor or ARB |

33 (28) |

|

Statin |

31 (26) |

|

LV function parameters |

|

|

LV end systolic diameter (mm) |

29±5 |

|

LV end diastolic diameter (mm) |

48±4 |

|

LV ejection fraction (%) |

63±6 |

|

LA diameter (mm) |

37±5 |

|

LA volume index (mL/m2) |

36.6±10.8 |

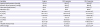

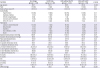

Table 2 shows the hemodynamic data at each stage of the diastolic stress test. At rest, the mean values of E/A, E/e', LA volume index, and TR peak velocity were 0.7±0.1, 12.0±1.4, 36.6±10.8 mL/m

2, and 2.3±0.2 m/s, respectively. According to the recently published guidelines and recommendations for the evaluation of LV diastolic function by echocardiography,

8) only 4 patients (1%) could be classified to have diastolic dysfunction. Fifty patients (42%) were classified to have normal diastolic function and the remaining 66 (55%) remained to be indeterminate. Estimation of LVFP in these patients with indeterminate classification revealed that moderate (n=39, 59.1%) had normal LVFP and the remaining 27 had increased LVFP.

Table 2

Hemodynamic variables at each stage of the diastolic stress test

|

Variables |

Supine |

25 W exercise |

50 W exercise |

|

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

137±14 |

156±19*

|

162±22†,§

|

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

82±10 |

90±14*

|

89±16§

|

|

Pulse rate (beat/minute) |

68±11 |

93±12*

|

104±17†,§

|

|

Saturation (%) |

97±1 |

97±2 |

96±2§

|

|

E (cm/s) |

61.2±11.0 |

101±17.4*

|

115.4±21.0†,§

|

|

A (cm/s) |

84.4±12.3 |

106.1±18.8*

|

115.7±24.0†,§

|

|

E/A |

0.73±0.12 |

0.97±0.18*

|

1.03±0.22†,§

|

|

e′ (cm/s) |

5.1±1.0 |

7.5±1.5*

|

8.2±1.9†,§

|

|

a′ (cm/s) |

9.3±1.4 |

12.6±2.5*

|

13.8±2.9†,§

|

|

E/e′ |

12.0±1.39 |

13.61±2.52*

|

14.60±3.40†,§

|

|

TR peak velocity (m/s) |

2.3±0.2 |

2.9±0.3*

|

3.1±0.4†,§

|

|

sPAP (mmHg) |

26.2±4.3 |

44.1±7.8*

|

50.0±10.3†,§

|

Patients with impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP showed various patterns of hemodynamic change during low-level supine bicycle exercise (

Figure 1). During exercise, 34 patients did not develop EiPH or hLVFP (group 1,

Figure 1A), 22 showed hLVFP only (group 2,

Figure 1B), 40 (33%), developed EiPH without hLVFP (group 3,

Figure 1C), and the remaining 25 showed EiPH with hLVFP (group 4,

Figure 1D). After 50 W exercise 14 patients (12%) were reclassified to diastolic dysfunction and 56 (47%) were indeterminate, according to current guideline for diastolic function.

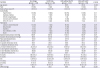

Table 3 shows the baseline clinical and hemodynamic variables according to the 4 patterns of hemodynamic response during the diastolic stress test. Patients with EiPH (groups 3 and 4) were characterized by a higher mean age and higher TR peak velocity/sPAP compared with those of the other groups. The number of significant dyspnea (NYHA II or III) was in higher in patients with hLVFP (groups 2 and 4) compared with patients without hLVFP (groups 1 and 3) (43% vs. 22%, p=0.024).

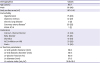

Table 4 summarizes the changes of the hemodynamic variables during supine exercise according to 4 different patterns during diastolic stress test. E/e' did not increase significantly during exercise in patients of groups 1 and 3, whereas gradual increase in E/e' was noticed in patients of groups 2 and 4, which resulted in significant increase of E/e' at 50 W stage compared to resting state. TR peak velocity and sPAP showed gradual increase during exercise irrespective of different patterns of hemodynamic response, and significant increases in TR peak velocity and sPAP at 50 W stage compared to resting state were observed in all groups. There was no significant correlation between changes of E/e' and that of TR peak velocity or sPAP in all patients, which was also observed in individual groups.

| Figure 1

Representative Doppler tracings of patients with impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP who showed (A) no significant change, (B) hLVFP without pulmonary hypertension, (C) pulmonary hypertension without hLVFP and (D) pulmonary hypertension with hLVFP during diastolic stress echocardiography.

hLVFP = high left ventricular filling pressure; TR = tricuspid regurgitation; W = watts.

|

Table 3

Baseline clinical variables according to the patterns of hemodynamic response during the diastolic stress test

|

Variables |

No change (group 1, n=33) |

hLVFP only (group 2, n=22) |

EiPH without hLVFP (group 3, n=40) |

EiPH with hLVFP (group 4, n=25) |

p value |

|

Age (years) |

62±7 |

62±7 |

66±6 |

68±8 |

0.003 |

|

Male |

19 (58) |

9 (41) |

17 (43) |

13 (52) |

0.51 |

|

Body surface area (m2) |

1.67±0.16 |

1.69±0.18 |

1.65±0.16 |

1.66±0.15 |

0.82 |

|

Comorbidity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertension |

16 (48) |

15 (68) |

30 (75) |

14 (56) |

0.13 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

5 (15) |

7 (32) |

12 (30) |

8 (32) |

0.41 |

|

Chronic lung disease |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (3) |

1 (4) |

0.59 |

|

Coronary artery disease |

11 (33) |

4 (18) |

8 (20) |

4 (16) |

0.54 |

|

NYHA FC II or III |

6 (3) |

9 (41) |

10 (25) |

11 (4) |

0.10 |

|

Medication |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calcium channel blocker |

10 (30) |

7 (32) |

18 (45) |

9 (36) |

0.29 |

|

Beta-blocker |

5 (15) |

4 (18) |

8 (20) |

8 (32) |

0.44 |

|

Diuretics |

4 (12) |

2 (9) |

6 (15) |

2 (8) |

0.70 |

|

ACE inhibitor or ARB |

10 (30) |

7 (32) |

11 (28) |

5 (20) |

0.74 |

|

Statin |

6 (18) |

5 (23) |

14 (35) |

6 (24) |

0.29 |

|

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

136±11 |

135±15 |

142±13 |

133±17 |

0.07 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

82±8 |

80±10 |

87±10 |

78±8 |

0.003 |

|

Pulse rate (beat/minute) |

70±12 |

68±9 |

67±10 |

66±11 |

0.46 |

|

Saturation (%) |

97±1 |

97±1 |

97±1 |

97±1 |

0.81 |

|

LV systolic dimension (mm) |

29±5 |

28±6 |

29±6 |

29±4 |

0.90 |

|

LV diastolic dimension (mm) |

47±4 |

49±4 |

48±5 |

48±5 |

0.49 |

|

LA volume index (mL/m2) |

33.2±10.4 |

36.3±12.6 |

37.9±10.1 |

39.0±10.1 |

0.17 |

|

LV end-systolic volume (mL) |

34±12 |

33±13 |

35±15 |

34±9 |

0.97 |

|

LV end-diastolic volume (mL) |

88±25 |

89±30 |

91±24 |

95±29 |

0.77 |

|

LV ejection fraction (%) |

61±4 |

63±5 |

63±7 |

64±5 |

0.37 |

|

E (cm/s) |

69.9±15.4 |

72.9±12.6 |

67.5±13.3 |

71.3±13.6 |

0.47 |

|

A (cm/s) |

80.5±11.1 |

87.9±13.5 |

82.8±16.2 |

87.8±15.8 |

0.14 |

|

E/A |

0.87±0.15 |

0.83±0.09 |

0.84±0.19 |

0.84±0.22 |

0.83 |

|

e′ (cm/s) |

5.9±1.0 |

5.9±1.0 |

5.6±1.1 |

5.7±1.0 |

0.58 |

|

a′ (cm/s) |

9.4±1.5 |

9.5±2.3 |

9.1±1.4 |

8.7±1.2 |

0.25 |

|

E/e′ |

11.88±1.51 |

12.42±1.37 |

12.12±1.43 |

12.60±1.32 |

0.19 |

|

sPAP (mmHg) |

25±5 |

25±5 |

29±4 |

28±4 |

<0.001 |

Table 4

Hemodynamic changes during diastolic stress test in each group

|

Groups |

No change (group 1, n=33) |

hLVFP only (group 2, n=22) |

EiPH without hLFP (group 3, n=40) |

EiPH with hLVFP (group 4, n=25) |

p value†

|

|

Supine |

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

136±11 |

135±15 |

143±13 |

133±17 |

0.07 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

82±8 |

80±10 |

87±10 |

78±8 |

0.003 |

|

Pulse rate (beat/minute) |

70±12 |

68±9 |

67±10 |

66±11 |

0.46 |

|

Saturation (%) |

97±1 |

97±1 |

97±1 |

97±1 |

0.81 |

|

E (cm/s) |

69.9±15.4 |

72.9±12.6 |

67.5±13.3 |

71.3±13.6 |

0.47 |

|

A (cm/s) |

80.5±11.1 |

87.9±13.5 |

82.8±16.2 |

87.8±15.8 |

0.14 |

|

E/A |

0.87±0.15 |

0.83±0.09 |

0.84±0.19 |

0.84±0.22 |

0.83 |

|

e′ (cm/s) |

5.9±1.0 |

5.9±1.0 |

5.6±1.1 |

5.7±1.0 |

0.58 |

|

a′ (cm/s) |

9.4±1.5 |

9.5±2.3 |

9.1±1.4 |

8.7±1.2 |

0.25 |

|

E/e′ |

11.88±1.51 |

12.42±1.37 |

12.12±1.43 |

12.60±1.32 |

0.19 |

|

TR peak velocity (m/s) |

2.2±0.3 |

2.2±0.3 |

2.5±0.2 |

2.4±0.2 |

<0.001 |

|

sPAP (mmHg) |

25±5 |

25±5 |

29±4 |

28±4 |

<0.001 |

|

25 W |

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

153±17*

|

156±22*

|

162±17*

|

151±23*

|

0.16 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

90±12*

|

89±13*

|

93±12*

|

85±18*

|

0.19 |

|

Pulse rate (beat/minute) |

92±12*

|

92±14*

|

95±12*

|

93±12*

|

0.75 |

|

Saturation (%) |

97±3 |

97±1 |

97±3 |

97±2 |

0.90 |

|

E (cm/s) |

96.6±17.5*

|

110.5±21.1*

|

95.6±15.5*

|

105.2±11.3*

|

0.002 |

|

A (cm/s) |

104.4±16.1*

|

109.0±22.6*

|

105.3±20.5*

|

106.9±16.1*

|

0.83 |

|

E/A |

0.94±0.18*

|

1.03±0.19*

|

0.93±0.17*

|

1.00±0.16*

|

0.07 |

|

e′ (cm/s) |

7.9±1.7*

|

7.4±1.6*

|

7.7±1.3*

|

6.9±1.0*

|

0.06 |

|

a′ (cm/s) |

13.1±2.6*

|

12.2±2.7*

|

12.7±2.3*

|

11.8±2.4*

|

0.20 |

|

E/e′ |

12.36±1.72*

|

15.21±2.42*

|

12.64±2.01 |

15.42±2.53*

|

<0.001 |

|

TR peak velocity (m/s) |

2.6±0.3*

|

2.6±0.3*

|

3.1±0.2*

|

3.0±0.3*

|

<0.001 |

|

sPAP (mmHg) |

38±6*

|

38±5*

|

50±6*

|

48±6*

|

<0.001 |

|

50 W |

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

159±19*,§

|

163±25*

|

168±22*

|

156±24*

|

0.14 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

91±15*

|

87±17*

|

92±14*

|

86±19*

|

0.41 |

|

Pulse rate (beat/minute) |

103±17*,§

|

104±16*,§

|

109±19*,§

|

101±12*,§

|

0.27 |

|

Saturation (%) |

97±2 |

96±2 |

96±2 |

97±2*

|

0.96 |

|

E (cm/s) |

109.8±21.2*,§

|

123.4±22.4*,§

|

108.4±17.7*,§

|

126.9±17.6*,§

|

<0.001 |

|

A (cm/s) |

114.0±18.8*,§

|

119.7±30.4*,§

|

114.4±26.4*,§

|

116.5±20.6*,§

|

0.82 |

|

E/A |

0.97±0.18*

|

1.08±0.25*

|

0.98±0.22*,§

|

1.11±0.22*,§

|

0.031 |

|

e′ (cm/s) |

9.0±1.9*,§

|

7.2±1.5*

|

8.8±1.9*,§

|

7.0±0.9*

|

<0.001 |

|

a′ (cm/s) |

14.6±3.1*,§

|

13.3±2.5*,§

|

14.2±3.2*,§

|

12.8±2.0*

|

0.07 |

|

E/e′ |

12.42±1.87 |

17.36±2.03*,§

|

12.49±1.66 |

18.42±2.90*,§

|

<0.001 |

|

TR peak velocity (m/s) |

2.7±0.3*,§

|

2.8±0.3*,§

|

3.4±0.2*,§

|

3.5±0.2*,§

|

<0.001 |

|

sPAP (mmHg) |

41±6*,§

|

42±6*,§

|

57±6*,§

|

59±7*,§

|

<0.001 |

A total of 65 patients (54%) developed EiPH during the test (groups 3 and 4). Multivariate analysis confirmed that age (odds ratio [OR], 1.066; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00–1.13; p=0.039) and resting sPAP (OR, 1.139; 95% CI, 1.02–1.27; p=0.018) were independent variables associated with EiPH development. During exercise, hLVP developed in 47 patients (groups 2 and 4). Diastolic blood pressure (OR, 0.944; 95% CI, 0.90–0.99; p=0.016) and A velocity at rest (OR, 1.040; 95% CI, 1.00–1.08; p=0.028) were independently associated with development of hLVFP in the multivariate analysis. Age (OR, 1.098; 95% CI, 1.02–1.18; p=0.016) was the only variable associated with development of EiPH and hLVFP (group 4). Lower E/e' (OR, 0.684; 95% CI, 0.50–0.98; p=0.036) and sPAP (OR, 0.881; 95% CI, 0.78–1.00; p=0.041) were associated with no significant hemodynamic changes during the test (group 1).

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that patients with both impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP showed variable hemodynamic responses during DSE using low-level supine bicycle exercise with Doppler echocardiography. Some patients developed hLVFP during exercise, and others showed EiPH with or without hLVFP. During the test, ≤30% patients showed no significant change in LVFP and sPAP. These results may indicate that patients with both impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP at resting echocardiography cannot be considered a homogeneous group, and DSE may be useful for further characterization of these patients.

Because of the successful clinical introduction of diastology into routine clinical practice, evaluation of diastolic function using Doppler echocardiography has become an essential diagnostic step in evaluating patients with clinical suspicion of heart failure.

13)14) The degree of diastolic dysfunction explains the functional status of heart failure and can provide critical prognostic information for patients with preserved or decreased LV systolic function.

15)16)17) The previous guidelines recommend using 3 major stages or grades of diastolic function, including abnormal relaxation, pseudonormal, and restrictive pattern.

1)18) However, likely because of the complex interactions of multiple inter-related events contributing to diastolic filling, the classification of diastolic stages continues to vary between observers, and many patients fall “between” stages.

2)

Using the recently published recommendations for the evaluation of LV diastolic function,

8) 42% of our subjects were classified to have normal diastolic function, whereas 66 patients (55%) remained to be indeterminate. In patients with normal diastolic function, the prevalence of groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 36.0%, 20.0%, 26.0%, and 18.0%, respectively. In patients with indeterminate diastolic function, the prevalence of groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 21.2%, 16.7%, 37.9%, and 24.2%, respectively. Four patients who were classified to have diastolic dysfunction all showed group 3 pattern (development of EiPH without hLVFP) during DSE. The frequency of different exercise hemodynamic patterns was not different between patients with normal diastolic function and those with indeterminate diastolic function. Thus, our subjects had different Doppler characteristics compared with those with “new diastolic dysfunction” reported by Kuwaki et al.

3) or those with “grade Ia diastolic dysfunction” reported by Pandit et al.

4) Our patients showed variable hemodynamic response during exercise, suggesting that patients with similar Doppler findings of diastolic function at rest do not necessarily have the same hemodynamic consequences. It is worthwhile to note that even the updated guidelines or “new classifications of diastolic stages” cannot prevent considerable proportions of patients from falling “between” stages or being left unclassified, which represents complex nature of diastolic function.

The subjects of our study had different Doppler inclusion criteria compared to the previous study,

3)4) which needs further explanation. The cutoff value of E/e' ≥10 was selected based on clinical data from simultaneous measurement of E/e' and LVFP during exercise.

7) In this validation study that included invasive measurement of LVFP at rest and during exercise, the authors found that post-exercise E/e' (septal) >13 was highly specific for identification of elevated LVFP during exercise and reduced exercise capacity with good correlation between E/e' and LVFP. Normal controls who showed normal LVFP at both rest and exercise showed mean resting E/e' value of 9.8±2.4 and patients who showed high LVFP at rest or with exercise had higher E/e' values at rest.

7) Thus, we used E/e' of ≥10 at rest as one of the selection criteria for indicating possibly high LVFP.

DSE performed in patients with both impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP in our present study showed interesting results characterized by markedly variable hemodynamic responses. Some patients developed hLVFP during exercise and others showed EiPH with and without hLVFP. In contrast, ≥30% showed no significant change in LV filling pressure and sPAP during exercise. The incidence of EiPH reported before was 34% (171/498),

10) which was lower compared with that reported here (54% [65/120]). Moreover, the relative incidence of patients with EiPH with hLVFP was significantly lower in our study (71% [122/171] vs. 38% [25/65]), suggesting that EiPH caused by a primary or isolated increase of pulmonary vascular resistance is more common in patients with impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP. The significant difference in the incidence of EiPH with hLVFP can be explained by different baseline characteristics of the subjects of the 2 studies, with a significantly higher mean age in our study (57±11 vs. 65±7 years). Age-related primary changes in the pulmonary vascular resistance associated with vascular remodeling likely explain the higher incidence of EiPH without hLVFP in these patients. In patients who developed EiPH, long-term outcomes are different between patients with and without hLVFP with worse prognosis in those with EiPH with hLVFP.

10) According to our current data acquired using the diastolic stress test, 21% (25/120) of patients with impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP were proven to show EiPH with hLVFP, and such patients are expected to have the most grave prognosis.

Development of hLVFP without EiPH in group 2 patients needs careful interpretation. During exercise, we observed that maximal velocity of TR jet gradually increases during exercise in all patients regardless of the hemodynamic patterns (

Table 4). However, E/e' did not increase during exercise in patients with groups 1 and 3. One interesting point is that, in patients with group 2, the peak velocity of TR and sPAP increases during exercise with progressive increase of E/e' but failed to failed to fulfill the criteria of EiPH.

10) This phenomenon has already been suggested in patients with left-sided valvular heart diseases by several investigators, who encouraged exercise test in various clinical conditions.

19)20)21) Although sPAP usually rises with exercise, total pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary arteriolar resistance change little or decrease.

22) A partial explanation of increase in sPAP includes the increase in stroke volume with increasing stress levels and an increase in LVFP with exercise.

23) The relative contribution of increased flow and increased LVFP or LA pressure to the increased sPAP remains unclear.

23)24) The discrepancy between E/e' and sPAP increase during exercise may reflect different changes in pulmonary vascular resistance determining stroke volume.

This study has several limitations. First, we exclusively used the septal e' velocity to assess LVFP, excluding entirely the lateral e' velocity. It is generally recommended to use the average of septal and lateral e' velocities to estimate LVFP, because the difference between the 2 cannot be easily ignored.

25) Current guidelines maintain that an average E/e' ratio (septal and lateral) >14 identifies those with hLVFP.

8) However, measurement of both velocities during the exercise stress test would not be feasible in many cases, and thus measurement of the septal e' velocity has been a practical approach during DES.

8)9)10)11) Second, absence of long-term outcome data supporting this cutoff value is an inherent limitation of this study and thus the clinical usefulness of baseline variables including age to predict EiPH is not certain. Although it was not employed during the DES in this study, the potential advantage of contrast to enhance Doppler signals for a more accurate estimation of sPAP and LVFP warrants further testing. Third, we arbitrarily used 50 W of supine exercise as the target of DSE, as Doppler recordings at 50 W were used for definition of EiPH or high LVFP during exercise in previous studies.

9)10) Symptom-limited exercise is usually recommended for patients with unexplained dyspnea to evaluate possible mechanisms. During maximal symptom-limited exercise, fusion of both early and late diastolic mitral inflow and annular velocities frequently develops, which makes it impossible to evaluate hemodynamic response of diastolic indices with exercise. For this specific purpose, the ideal target or index representing adequate “diastolic stress” is not established. Moreover, it is unknown whether a different work loading not equal to 50 W during supine exercise would provide better hemodynamic data to assess diastolic dysfunction. In addition, we used arbitrary selection criteria of patients with impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP using E/A ratio and E/e'. Further study would be necessary using different criteria.

In conclusion, this study reveals that patients with impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP defined as E/A ratio <1.0 and 10≤ E/e' <15, which will be classified to have ‘indeterminate diastolic function group’ according to new guideline, showed markedly variable hemodynamic responses during low-level supine bicycle exercise. Development of EiPH with hLVFP, a presumably ominous prognostic sign, occurred in less than <25% of patients who cannot be classified with impaired relaxation or pseudonromal pattern, and age was strongly associated with this hemodynamic change. Patients with both impaired relaxation and possibly hLVFP subjected to resting echocardiography cannot be considered a homogeneous group, and DSE may be useful for further characterization and risk stratification of these patients. Further investigations are necessary to evaluate the clinical impact of this test in selected patients with specific symptoms of heart failure.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download