Abstract

Background

Although clinicians, nurse specialists, pharmacists, and nutritionists expend significant time and resources in optimizing care for patients with diabetes, the effectiveness of integrated diabetes care team approach remains unclear. We assessed the effects of a multidisciplinary team care educational intervention on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels among diabetes patients.

Methods

We conducted a matched case-control study in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes, comparing the propensity scores pertaining to the effectiveness in reducing HbA1c levels between a group receiving an educational intervention and a control group. We included 40 pairs of patients hospitalized between June 2014 and September 2016. HbA1c values measured at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months were compared between the two groups.

Results

The educated group showed an improvement in HbA1c levels compared to the control group at 3 months (6.3 ± 2.3% vs. 9.5 ± 4.0%; P = 0.020) and at 6 months (7.5 ± 1.5% vs. 9.6 ± 3.0%; P = 0.106). There was a significant difference in the change in mean HbA1c from baseline to 3 months between the two groups (−35.7 ± 26.1% vs. −9.1 ± 20.5%; P = 0.013).

The prevalence of diabetes is increasing worldwide. The number of people with diabetes reached 422 million in 2014, and diabetes caused 1.5 million deaths in 2012 [1]. Despite tremendous advances in treatment over the last few decades, reducing mortality and morbidity in diabetic patients through adequate blood glucose control remains challenging.

Diabetes is a chronic disease that requires numerous daily self-care-related decisions and behaviors pertaining to food choices, physical activity, and medication use. Diabetes education improves knowledge and skills related to the control of diabetes, which is essential for people with the disease [2]. Diabetes education has been considered an important facet of the clinical management of individuals with diabetes since the 1930s [3]. The American Diabetes Association recommends assessments of diabetes self-management skills and knowledge, and the provision of diabetes education at the time of diagnosis on an, annual basis, and whenever a complication arises or transition in care occurs [2]. Diabetes education has been reported to improve blood glycemic control and reduce diabetic complications [4567]. In addition, diabetes education reduces the hospitalization and re-admission rate of diabetic patients, thereby reducing the economic burden of treatment [89].

In most diabetes educational interventions, diverse educators, such as clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, exercise therapists, and social workers address diabetic patients individually, according to their own specific areas of expertise. Because the conditions of diabetic patients are so diverse, a uniform educational approach based on a single discipline has limitations. Each educator may emphasize the importance of his or her field without knowing what problems the patient has that are relevant to other fields, and patients could be confused due to a lack of understanding of the multilevel problems that they may encounter. In addition, there are invisible barriers in communication among diabetes educators. Therefore, diabetes education is expected to be more effective when integrated education is provided, rather than an individualistic approach.

In this study, we evaluated the effect of a multidisciplinary diabetes educational intervention, provided by a team of clinicians, nurse specialists, pharmacists, and nutritionists, on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels among diabetes patients.

In this matched case-control study, 141 patients hospitalized with type 2 diabetes were recruited at the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Pusan National University Hospital. The protocols and consen t procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital (approval no. 20140223).

We enrolled 40 patients in the education group who were hospitalized between June 2014 and September 2016, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, aged above 18 years, able to communicate normally, and who agreed to take part in multidisciplinary team care sessions. Patients with cancer or severe illnesses, and those with communication problems, were excluded from the study. The control group consisted of 101 patients who were admitted during the same period and met the same exclusionary criteria as the education group, but did not receive education from the multidisciplinary team. Both education and control groups were admitted for blood glucose control. All of the education group patients had never received a team-based education before agreeing to this study. There was a significant difference in HbA1c level between the education and control groups; therefore, 27 pairs of hospitalized patients were matched using propensity scores. Propensity score matching analysis was performed with support from Department of Biostatistics of Pusan National University Hospital.

The multidisciplinary team consisted of clinicians, nurse specialists, pharmacists, and nutritionists. When a hospitalized patient meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the clinician requested the multidisciplinary team care sessions after obtaining the patient's consent. The multidisciplinary team care sessions were performed once a week, and more than once during the hospital stay. Before the multidisciplinary team care sessions, the clinician, nurse specialist, pharmacist, and nutritionist individually assessed and interviewed the patient. The nurse specialist educated patients on how to properly administer insulin, and patient performance with respect to insulin injections was measured by the Performance Accuracy Questionnaire for Insulin Injection (Supplementary Table 1). The pharmacist educated patients about oral hypoglycemic agents, and medication compliance was measured by the Modified Morisky Scale (Supplementary Table 2). The nutritionist educated patients about the diabetic diet. The nutrition assessment, diagnosis, and intervention were evaluated according to nutritional counseling results (Supplementary Table 3). On the day of the multidisciplinary team care session, all team members convened just before the session to present and discuss the patient's condition. The clinician led the multidisciplinary team care sessions, which were held during the patient's lunch time. After each round of multidisciplinary team care, the team members discussed the patient and wrote a report.

All patient charts were reviewed by the same clinician. HbA1c levels were measured at the time of enrollment, and at 3 and 6 months post-enrollment. HbA1c levels measured at 3 and 6 months included data collected 1 month before and after.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (ver. 9.3.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R software (ver. 3.3.2; R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as median (interquartile range) for skewed variables. Differences between the two groups were analyzed by parametric two-sample t-tests and non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The chi-squared test was applied to analyze categorical variables. The nearest neighbor matching method was used to classify the education group based on the similarity to the control group propensity score. A twotailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

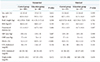

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the patients with type 2 diabetes. Sex, age, body mass index, duration of diabetes, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and lipid profiles did not significantly differ between the education group and the control group. HbA1c levels were higher in the education group than in the control group in an unmatched case-control study. Table 2 shows differences in the status of baseline medication between the two groups. There were no patients treated with oral antidiabetic drugs in the education group, and a basal-bolus insulin regimen was more common in the education group than in the control group.

In the education group, the HbA1c level was significantly reduced, from 10.2 ± 2.0% to 6.3 ± 2.3%, after 3 months of multidisciplinary team-based diabetes education (Fig. 1A). In the control group, the HbA1c level was reduced from 10.0 ± 3.1% to 9.5 ± 4.0% after 3 months. After 3 months, the reduction rate was −35.7 ± 26.1% in the education group and −9.1 ± 20.5% in the control group (Fig. 1B), and there was a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.013; Table 3).

The HbA1c level in the education group after 6 months was 7.5 ± 1.5%, which was slightly higher th an that after 3 months. The HbA1c level after 6 months in the control group was 9.6 ± 3.0%. The HbA1c level of the education group tended to be lower than that of the control group after 6 months, but the difference in HbA1c level between the two groups after 6 months was not significant (P= 0.106).

In this study, patients who received team-based diabetes education had lower HbA1c levels at the 3-month follow-up than the non-educated control group patients. This suggests that a multidisciplinary educational intervention provided by clinicians, nurse specialists, pharmacists, and nutritionists can increase the effectiveness of treatment for diabetic patients.

Previous studies have shown that various forms of diabetes education are associated with lower HbA1c levels in diabetes patients. Steinsbekk et al. [10] reported that group-based diabetic self-management education in adult type 2 diabetes patients reduced the HbA1c level by 0.87% and improved diabetic knowledge and self-management skills. Norris et al. [5] reported that self-management education lowered the HbA1c level by 0.76%. According to a study by Kim et al. [6] done in Korea, the HbA1c level decreased from 7.84% to 6.79% following self-management education. Several previous studies have also reported a reduction in HbA1c of about 1% after diabetes education [11121314]. In this study, 3 months after team-based diabetes education, the HbA1c level decreased from 10.2 ± 2.0% to 6.3 ± 2.3%, a considerable change compared to previous studies. However, this may be due to the effects of increased diabetic medication use.

According to the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), a 1% reduction in the HbA1c level over 10 years reduces the risk of diabetes-related death by 21%, reduces myocardial infarction risk by 14%, and reduces the microvascular complication rate by 36% [15]. Therefore, the decrease in HbA1c level from 10.2 ± 2.0% to 6.3 ± 2.3% after 3 months in this study was very meaningful. However, there was no significant difference in HbA1c between the education group and the control group after 6 months. Norris et al. [5] reported that the initial effects of diabetes education decreased after 6 months. Brown reported that the effects peaked 1 to 6 months after intervention, and decreased to back to the initial level after 6 months [16]. The effects of education decreased with longer follow-up intervals after the intervention in the study by Norris et al. [5]. This trend is common not only among studies of diabetes education, but also in studies of other behavioral interventions for weight loss [171819]. Although diabetes education is effective, the data suggest that the benefit does not persist. For diabetes education to effectively reduce long-term complications, the initial effects of glycemic control must be maintained over the long-term. Therefore, regular and continuous long-term intervention is required.

The limitations of this study were as follows. First, drug treatments were not taken into consideration, although medication changes can affect treatment effectiveness. Second, the patient enrollment rate was low, and follow-up loss was high. Third, we did not investigate changes such as complications other than HbA1c. Fourth, there was no assessment of changes in the method of drug administration, the method of insulin injection, compliance with medication, dietary control, etc. Despite these limitations, this study is meaningful as the first study to paradoxically emphasize the importance of team-based education in the management of type 2 diabetes when considering the clinical situation in Korea where it is not easy for diabetes education to satisfy both patients and medical staff within a limited time.

In this study, the positive effect on glycemic control seen after the team-based diabetes education intervention was presumably due to appropriate administration methods, and improvements in compliance with medications, dietary habits, and insulin use. Multidisciplinary education delivered by clinicians, nurse specialists, pharmacists, and nutritionists can lead to proper glycemic control and, ultimately, a reduction in diabetes complications and mortality. Continuous follow-up and education on the various factors influencing glycemic control are required for sustained effectiveness. However, it is difficult to provide a team-based diabetes education intervention t o all diabetes patients. In practice, patients often receive medication in small primary clinics as well as in large hospitals, and it is rare to encounter diabetes experts other than doctors at these primary clinics. Previous studies reported variously that only 26.2% and 39.4% of diabetes patients received diabetes education [2021]. The effectiveness of diabetes education has already been shown in multiple studies; thus, it is necessary to find ways to overcome the limitations associated with practical application of diabetes education.

In conclusion, this study showed that team-based diabetes education, involving clinicians, nurse specialists, pharmacists, and nutritionists, improved glycemic control in diabetes patients. Further research is needed to determine whether the long-term effects of team-based diabetes education lead to long-term maintenance of target HbA1c levels and thus reduce the rate of diabetic complications.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Changes in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) from baseline at 3 and 6 months. (B) Time-course of mean HbA1c between education group and control group in patients with type 2 diabetes. Values are presented as mean ± 95% confidence interval. |

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the patients with type 2 diabetes

Values are presented as number (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and frequencies (percentage) for categorical variables.

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by a grant (W.J.K., 2014) from the Korean Diabetes Association. We thank Department of Biostatistics, Clinical Trial Center, Biomedical Research Institute, Pusan National University Hospital.S

References

1. World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. updated 2016. Available from: www.who.int/diabetes/global-report.

2. Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, Duker P, Funnell MM, Hess Fischl A, Maryniuk MD, Siminerio L, Vivian E. Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes: a joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diabetes Care. 2015; 38:1372–1382.

3. Bartlett EE. Historical glimpses of patient education in the United States. Patient Educ Couns. 1986; 8:135–149.

4. Gagliardino JJ, Aschner P, Baik SH, Chan J, Chantelot JM, Ilkova H, Ramachandran A. IDMPS investigators. Patients' education, and its impact on care outcomes, resource consumption and working conditions: data from the International Diabetes Management Practices Study (IDMPS). Diabetes Metab. 2012; 38:128–134.

5. Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002; 25:1159–1171.

6. Kim MY, Suh S, Jin SM, Kim SW, Bae JC, Hur KY, Kim SH, Rha MY, Cho YY, Lee MS, Lee MK, Kim KW, Kim JH. Education as prescription for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: compliance and efficacy in clinical practice. Diabetes Metab J. 2012; 36:452–459.

7. Choi MJ, Yoo SH, Kim KR, Bae YM, Ahn SH, Kim SS, Min SA, Choi JS, Lee SE, Moon YJ, Rhee EJ, Park CY, Lee WY, Oh KW, Park SW, Kim SW. Effect on glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid control according to education types. Diabetes Metab J. 2011; 35:580–586.

8. Healy SJ, Black D, Harris C, Lorenz A, Dungan KM. Inpatient diabetes education is associated with less frequent hospital readmission among patients with poor glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36:2960–2967.

9. Robbins JM, Thatcher GE, Webb DA, Valdmanis VG. Nutritionist visits, diabetes classes, and hospitalization rates and charges: the Urban Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31:655–660.

10. Steinsbekk A, Rygg LØ, Lisulo M, Rise MB, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012; 12:213.

11. Tshiananga JK, Kocher S, Weber C, Erny-Albrecht K, Berndt K, Neeser K. The effect of nurse-led diabetes self-management education on glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2012; 38:108–123.

12. Welch G, Zagarins SE, Feinberg RG, Garb JL. Motivational interviewing delivered by diabetes educators: does it improve blood glucose control among poorly controlled type 2 diabetes patients? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011; 91:54–60.

13. Deakin T, McShane CE, Cade JE, Williams RD. Group based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; (2):CD003417.

14. Gary TL, Genkinger JM, Guallar E, Peyrot M, Brancati FL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioral interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2003; 29:488–501.

15. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, Hadden D, Turner RC, Holman RR. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000; 321:405–412.

16. Brown SA. Meta-analysis of diabetes patient education research: variations in intervention effects across studies. Res Nurs Health. 1992; 15:409–419.

17. Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24:561–587.

18. Wing RR, Goldstein MG, Acton KJ, Birch LL, Jakicic JM, Sallis JF Jr, Smith-West D, Jeffery RW, Surwit RS. Behavioral science research in diabetes: lifestyle changes related to obesity, eating behavior, and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24:117–123.

19. Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In : Bray GA, Bouchard C, James WPT, editors. Handbook of obesity. New York: Marcel Dekker;1998. p. 855–873.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download