Abstract

Background and Purpose

Mechanical thrombectomy with or without intravenous thrombolysis is indicated in the acute treatment of ischemic strokes caused by an emergent large-vessel occlusion (ELVO) within 6 hours from symptom onset. However, a significant proportion of patients are referred to comprehensive stroke centers beyond this therapeutic time window. This study performed a pooled analysis of data from trials in which mechanical thrombectomy was performed beyond 6 hours from symptom onset.

Methods

We searched for randomized controlled trials that compared mechanical thrombectomy with the best medical treatment beyond 6 hours for ischemic strokes due to ELVO and reported on between 1990 and April 2018. The intervention group comprised patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy. Statistical analysis was conducted while pooling data and analyzing fixed- or random-effects models as appropriate.

Results

Four trials involving 518 stroke patients met the eligibility criteria. There were 267 strokes treated with mechanical thrombectomy, with a median time of 10.8 hours between when the patient was last known to be well to randomization. We observed a significant difference between groups concerning the rate of functional independence at 90 days from stroke, with an absolute difference of 27.5% (odds ratio=3.33, 95% CI=1.81–6.12, p<0.001) and good recanalization (odds ratio=13.17, 95% CI=4.17–41.60, p<0.001) favoring the intervention group.

Mechanical thrombectomy with or without intravenous thrombolysis is indicated in the acute treatment of ischemic strokes due to an emergent large-vessel occlusion (ELVO). A recent analysis found functional independence rates after endovascular treatment of 64% and 46% within 3 and 8 hours from symptom onset, respectively.1 That pooled individual analysis showed an improved outcome for times from symptom onset to recanalization of up to 7.3 hours. The main factor that contributed to the positive results of previous trials using mechanical thrombectomy was the selection of patients based on detecting ELVO using emergency CTA. These results have led to endovascular procedures and indirectly the use of radiological examinations increasing over the past 2 years.2

However, a significant proportion of patients are referred to comprehensive stroke centers beyond the 6 hours that is indicated as being the significant therapeutic window in several international guidelines. Some previous studies found that the size of the core infarct and ischemic penumbra are dependent on the collateral flow and the time from symptom onset,3 drawing attention to the neuroimaging criteria in addition to the time. In particular, two recent trials treated stroke patients with mechanical thrombectomy beyond 6 hours based on criteria that included evaluations of the size mismatch between the core infarct and ischemic penumbra.45

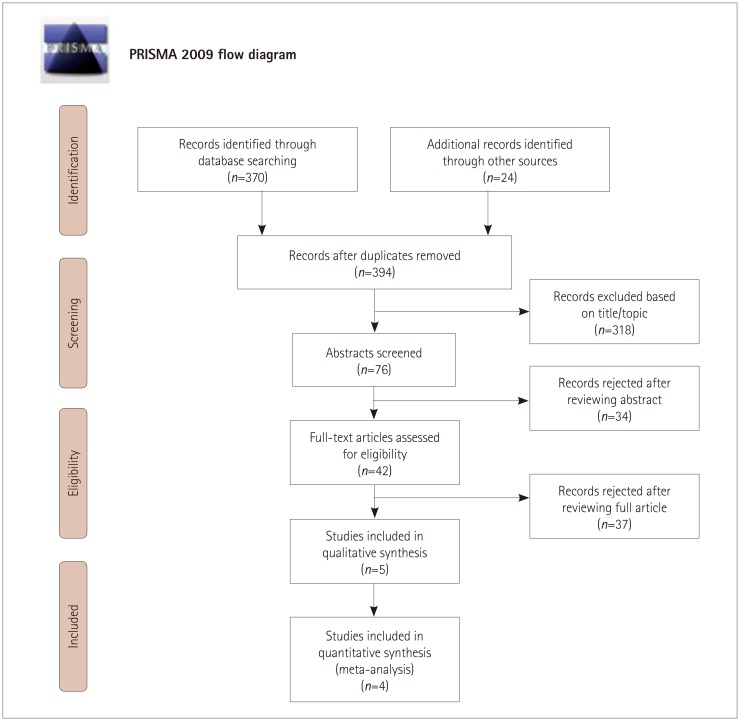

Two reviewers systematically searched PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from January 1990 up to April 1, 2018. We conducted this search and meta-analysis in accordance with the statements of the PRISMA Collaborative Group. Specific terms were used as either MeSH categories or keywords, including “stroke,” “brain ischemia,” “endovascular,” “mechanical thrombectomy,” “stent retriever,” “time to treatment,” and “time to recanalization”. Reference lists and cited articles were also reviewed to increase the identification rate of relevant studies.

We developed predefined criteria before performing the study review. We included in the analysis only randomized controlled trials of clinical and functional outcomes for acute ischemic stroke patients with anterior circulation occlusions and treated with mechanical thrombectomy versus the best medical treatment beyond 6 hours after symptom onset. We limited the studies to the English language and excluded case reports, conference presentations, E-posters, abstracts, and reviews. The intervention group comprised patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy alone or in combination with other medical treatments (e.g., intravenous thrombolysis), while the patients in the control group were only treated pharmacologically (i.e., without endovascular procedures). The minimum core inclusion criteria from neuroimaging were brain CT/MRI and CTA/MRA diagnosing an ischemic stroke with an ELVO of the anterior circulation.

The primary endpoint was functional independence at 90 days from stroke onset, considered as a score on the modified Rankin Scale of less than 3. Secondary endpoints were the rate of good recanalization as assessed by the TICI grade (2b or 3), the mortality rate at 90 days from stroke onset, and the occurrence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) as defined by European-Australasian Cooperative Acute Stroke Study 2.6

Two reviewers independently extracted data concerning the baseline and outcome characteristics of each included study and the trial design. We report where there was a lack of study information concerning an outcome. Different risks of bias were reported using the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention.

We performed a statistical analysis pooling data in the intervention group and the control group. Outcome heterogeneity was evaluated with Cochrane's Q test and I2. An overall p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Meta-analysis for overall outcomes was conducted using fixed-effects models (Mantel-Haenszel method) and random-effects models (DerSimonian and Laird method) to statistically compare studies according to the outcome heterogeneity. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI values were calculated for all outcomes. We report the findings graphically using forest plots for outcome results of single included trials and total treatment effects. We also calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) for the primary endpoint. Data analysis was performed using Review Manager (version 5.3, The Cochrane Collaboration 2012, Copenhagen, Denmark).

In total, 394 potential studies were initially identified, of which only the following 4 trials met the eligibility criteria following reviewer evaluations: ESCAPE, REVASCAT, DEFUSE-3, and DAWN.4578 Only some subgroup analyses were considered for two of the studies,78 and in particular for REVASCAT we were able to extract data on functional independence and death at 90 days from stroke onset.

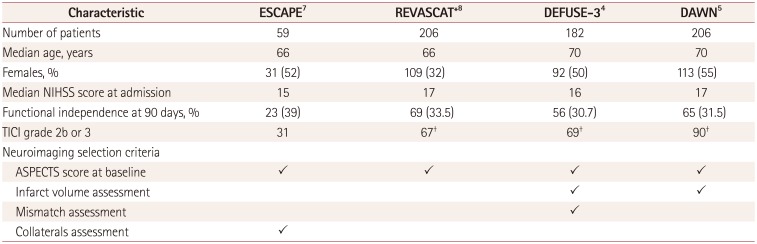

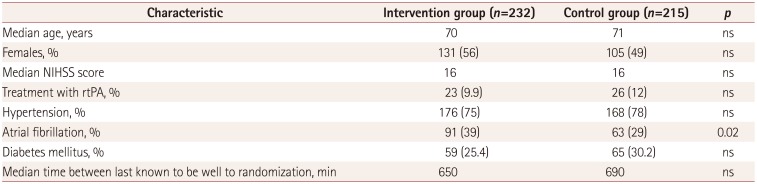

Fig. 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the search procedure. The main trial characteristics are presented in Table 1. The analysis included 518 stroke patients, of which 267 were treated with mechanical thrombectomy (intervention group) and 251 were received medical treatment alone (control group). The median age was 70 years, and 236 patients were female. The clinical severity was moderate at admission (median NIHSS score=16), while hypertension was the main vascular risk factor (n=344, 66.5%). About 9.5% of the patients (n=49) were treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. There were no significant differences between groups concerning demographic and clinical characteristics, with the exception of the rate of atrial fibrillation being higher in the intervention group than in the control group (Table 2).

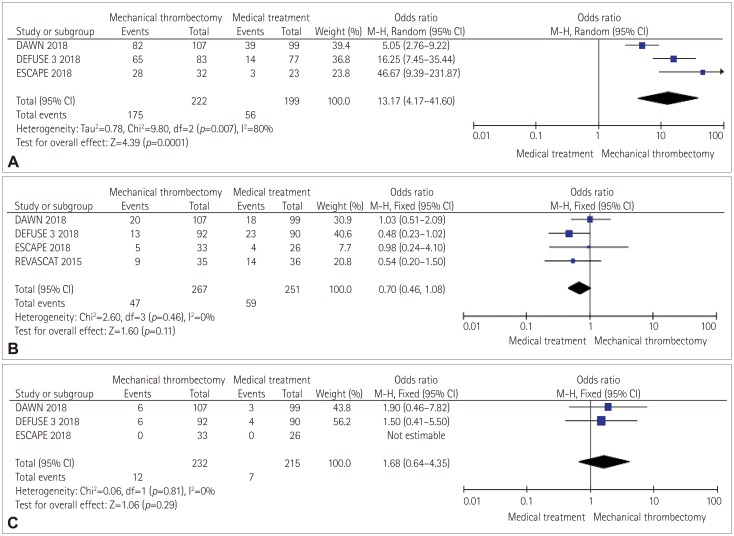

Functional independence was reached at the 90-day follow-up after stroke by 124 patients (46.4%) in the intervention group compared to 18.9% of those in the control group. The pooled analysis revealed a superiority of mechanical thrombectomy over medical treatment alone for the primary endpoint (OR=3.33, 95% CI=1.81–6.12, p<0.001). We found that significant heterogeneity was present (chi square=6.33, I2=53%). Single-trial and overall effects are presented in the forest plot in Fig. 2. NNT was 3.6. Endovascular treatment showed significant superiority in achieving recanalization over medical treatment alone (OR=13.17, 95% CI=4.17–41.60, p<0.0001). However, we also observed greater heterogeneity in the pooled analysis (chi square=9.80, I2=80%). The death rate at 90 days from stroke did not significantly differ between groups, even if we observed a higher rate in the interventional group (OR=0.70, 95% CI=0.46–1.08, p=0.11). Finally, the incidence of symptomatic ICH was higher in the intervention group than in the medical-treatment group (5.1% vs. 3.25%). However, in the pooled analysis we found no statistically significant difference between the groups (OR=1.68, 95% CI=0.64–4.35, p=0.29) and no heterogeneity (chi square=0.06, I2=0%) (Fig. 3).

This updated meta-analysis of randomized trials revealed that the application of mechanical thrombectomy to selected patients with ischemic stroke due to an ELVO significantly increases the rate of functional independence at 90 days after the ischemic event. We calculated an overall NNT of 3.6, which indicates superiority over other treatments and procedures (e.g., intravenous thrombolysis performed within 3 hours from symptom onset produced an NNT of 8).10 In light of these findings, the therapeutic window for endovascular procedures could be extended up to 24 hours. However, our pooled analysis revealed that the main benefits resulted in the last two trials that applied stricter inclusion and exclusion criteria. Indeed, the DAWN and DEFUSE-3 trials required the assessment of two or more advanced neuroimaging findings at admission, as presented in Table 1. In particular, the absolute differences in the rate of functional independence at 90 days were 36% and 28% in the DAWN and DEFUSE-3 trials, respectively. Comparing the different trials included in this meta-analysis reveals that the significant benefit decreased from the DAWN to the REVASCAT trial, with ORs of 6.25 and 1.50, respectively.

Considering the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, we observed that the use of perfusion techniques also at admission produced the best results for functional independence. The result was similar for achieving good recanalization (TICI grade of 2b or 3). While collateral flow is crucial in stroke physiology and the core infarct size is independent of the time to presentation,1112 recanalization remains a key factor for achieving a good functional outcome.13 Very few patients in the present control group were treated with intravenous thrombolysis (12%). This low rate of reperfusion treatment could partly explain the intergroup differences in the rates of good recanalization and functional independence at 90 days from stroke. Recanalization is related to the time from symptom onset. However, the growth rate of the ischemic core has more recently been postulated as the essential time-dependent factor determining a positive or negative evolution of the clinical condition.14 Indeed, a rapid transformation of an ischemic penumbra into the core infarct reduces the benefit of recanalization significantly, even if this is performed rapidly. In contrast, a slow growth rate can produce a good final clinical result even if recanalization occurs later than beyond 6 hours.

In light of these physiological mechanisms, selecting patients based on perfusion techniques by CT or MRI makes it possible to effectively treat strokes with a matched core and penumbra also beyond the therapeutic window of 6 hours in current international guidelines. Moreover, we did not observe significant differences in symptomatic ICH between the groups. These results differ from those of a previous meta-analysis that included only observational studies and compared trials treating patients beyond and within 6 hours from symptom onset.15 In particular, the rates of functional independence at 90 days in the present and previous meta-analyses were 46.4% and 38.4%, respectively (chi square=5.098, 95% CI=1.051–14.968, p=0.02). Moreover, the mortality rate was lower in the present meta-analysis (17.6% vs. 22.8%). The selection criteria of some observational studies did not include clear definitions of perfusion imaging, clinical severity, or core-penumbra mismatch. In the more-recent randomized trials, the application of these criteria resulted in a significant increase in the benefit of mechanical thrombectomy despite a 6-hour time limit.

This meta-analysis was subject to some limitations. First, we observed heterogeneity in the pooled analysis; however, this statistical bias was reduced by applying a random-effects model. Second, the four included trials exhibited differences in imaging modalities and protocols (e.g., the inclusion and exclusion criteria concerning the use of neuroimaging applied at baseline), which could have introduced bias into the pooled analysis. However, we also observed some common criteria, such as in the detection of an ELVO and the assessment of the ASPECTS score at baseline. Third, we were not able to perform an individual data meta-analysis that could have allowed subgroups to be analyzed.

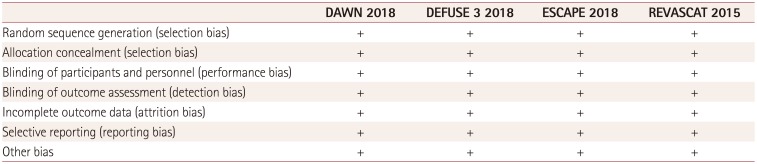

The strengths of the meta-analysis were the clear identification of very low risks of publication bias (Table 3) and only randomized controlled trials being included in the pooled analysis.

Recent studies and meta-analyses have shown a clear benefit of mechanical thrombectomy over intravenous thrombolysis alone on the functional outcome of stroke patients with ELVO within 6 hours from symptom onset.161718 The present meta-analysis suggests that this benefit remains also beyond the 6 hours after stroke onset, without any significant increase in the risk of symptomatic ICH, as long as patients are selected based on perfusion techniques combined with a clinical evaluation. As indicated in international guidelines,19 stroke patients with an ELVO and a limited core infarct may benefit from recanalization with mechanical thrombectomy, even if they present later than 6 hours after symptom onset.

References

1. Saver JL, Goyal M, van der Lugt A, Menon BK, Majoie CB, Dippel DW, et al. Time to treatment with endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes from ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016; 316:1279–1288. PMID: 27673305.

2. Smith EE, Saver JL, Cox M, Liang L, Matsouaka R, Xian Y, et al. Increase in endovascular therapy in Get With The Guidelines-Stroke after the publication of the pivotal trials. Circulation. 2017; 136:2303–2310. PMID: 28982689.

3. Bang OY, Goyal M, Liebeskind DS. Collateral circulation in ischemic stroke: assessment tools and therapeutic strategies. Stroke. 2015; 46:3302–3309. PMID: 26451027.

4. Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, Christensen S, Tsai JP, Ortega-Gutierrez S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:708–718. PMID: 29364767.

5. Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, Bonafe A, Budzik RF, Bhuva P, et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:11–21. PMID: 29129157.

6. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998; 352:1245–1251. PMID: 9788453.

7. Evans JW, Graham BR, Pordeli P, Al-Ajlan FS, Willinsky R, Montanera WJ, et al. Time for a time window extension: insights from late presenters in the ESCAPE trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018; 39:102–106. PMID: 29191873.

8. Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, de Miquel MA, Molina CA, Rovira A, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2296–2306. PMID: 25882510.

9. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6:e1000097. PMID: 19621072.

10. Kamal N, Majmundar N, Damadora N, El-Ghanem M, Nuoman R, Keller IA, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy-is time still brain? The DAWN of a new era. Br J Neurosurg. 2018; 2. 08. DOI: 10.1080/02688697.2018.1426726. [Epub].

11. Sheth SA, Sanossian N, Hao Q, Starkman S, Ali LK, Kim D, et al. Collateral flow as causative of good outcomes in endovascular stroke therapy. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016; 8:2–7. PMID: 25378639.

12. Liebeskind DS, Tomsick TA, Foster LD, Yeatts SD, Carrozzella J, Demchuk AM, et al. Collaterals at angiography and outcomes in the Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) III trial. Stroke. 2014; 45:759–764. PMID: 24473178.

13. Telischak NA, Wintermark M. Imaging predictors of procedural and clinical outcome in endovascular acute stroke therapy. Neurovasc Imaging. 2015; 1:4.

15. Wareham J, Phan K, Renowden S, Mortimer AM. A meta-analysis of observational evidence for the use of endovascular thrombectomy in proximal occlusive stroke beyond 6 hours in patients with limited core infarct. Neurointervention. 2017; 12:59–68. PMID: 28955507.

16. Badhiwala JH, Nassiri F, Alhazzani W, Selim MH, Farrokhyar F, Spears J, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015; 314:1832–1843. PMID: 26529161.

17. Vidale S, Agostoni E. Endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke: an updated meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2017; 51:215–219. PMID: 28424039.

18. Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DW, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016; 387:1723–1731. PMID: 26898852.

19. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018; 49:e46–e110. PMID: 29367334.

Fig. 3

Forest plots of the secondary endpoints: (A) good recanalization, (B) death at 90 days after stroke, and (C) symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

Table 1

Characteristics of the included trials

| Characteristic | ESCAPE7 | REVASCAT*8 | DEFUSE-34 | DAWN5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 59 | 206 | 182 | 206 |

| Median age, years | 66 | 66 | 70 | 70 |

| Females, % | 31 (52) | 109 (32) | 92 (50) | 113 (55) |

| Median NIHSS score at admission | 15 | 17 | 16 | 17 |

| Functional independence at 90 days, % | 23 (39) | 69 (33.5) | 56 (30.7) | 65 (31.5) |

| TICI grade 2b or 3 | 31 | 67† | 69† | 90† |

| Neuroimaging selection criteria | ||||

| ASPECTS score at baseline | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Infarct volume assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mismatch assessment | ✓ | |||

| Collaterals assessment | ✓ |

Table 2

Main demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 3

Judgements of the review authors about the risks of different bias types for each included study

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download