INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is a representative cause of food borne infection. Therefore, HAV infection is closely associated with sanitary conditions. In South Korea, stark economic development of the mid-1970s contributed to the reduction of incidences of acute HAV infection. However, an increasing number of adults without immunity for HAV led to the outbreak of acute HAV infection in 2009. Although raised arousal for HAV decreased the incidence of HAV infection, there is a trend for the recent rebound since 2013.

1 HAV infection is usually a self-limited disease. Autoimmune manifestations are rarely reported among patients with acute HAV infection. Ertem et al.

2 described two patients who developed immune thrombocytopenia and hepatic venous thrombosis during the course of acute HAV infection.

Graves' disease is the most common cause of thyrotoxicosis, and can be defined as a syndrome that is comprised of hyperthyroidism, goiter, orbitopathy, and dermopathy. In brief, the pathogenesis of this disease is the activation of the thyrotropin receptor by autoantibodies, thereby stimulating the thyroid hormone synthesis, leading to the growth of diffuse goiter. Given that this disease is mediated by autoantibodies, this disease is classified as an autoimmune disease.

34

As the precipitating cause of Graves' disease, several triggering factors have been addressed from the strongest genetic susceptibility to environmental factors, including smoking, pregnancy, infection, drug, and so on.

45678 In connection with viral hepatitis, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and even recently hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection have been reported as inducing factors of Graves' disease.

910111213 This study, to the best of our knowledge, introduces for the first time a case of acute HAV infection that might have triggered Graves' disease.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 27-year-old female presented fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea on February, 2017. These symptoms had manifested 4 days prior to visiting our hospital. The medical history and family history were unremarkable. There was no change of weight, and she was not on any medication.

Her initial vital signs were as follow: Blood pressure 120/90 mmHg, heart rate 122/min, respiratory rate 24/min, and body temperature 38.7℃. The cervical mass was moderately palpated without tenderness on the midline of neck. The abdomen was soft and flat, while bowel sound was hyperactive and tenderness was identified at the epigastrium.

The initial laboratory test results were: Hemoglobin 14.7 g/dL, white blood cell count 2,000/mm

3, platelet count 186,300/mm

3, CRP 19.9 mg/dL, AST 3,603 U/L, ALT 2,082 U/L, ALP 247 U/L, GGT 151 U/L, total bilirubin 2.30 mg/dL, total protein 6.8 g/dL, albumin 3.7 g/dL, PT INR 1.35, BUN 10.7 mg/dL, creatinine 0.4 mg/dL (

Table 1). Moreover, her thyroid function test performed just one year ago was normal, but this time, hyperthyroidism was identified, with a total T3 509 ng/dL (ref. 80–200 ng/dL), free T4 >7.77 ng/dL (ref. 0.93–1.7 ng/dL), and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.005 µIU/mL (ref. 0.27–5.0 µIU/mL).

Further tests had shown positive IgM anti-HAV and autoantibodies for TSH receptor 10.9 IU/L (ref. <1.75 IU/L), thyroid peroxidase 381.5 IU/mL (ref. <34.0 IU/mL), and thyroglobulin 300.8 IU/mL (ref. <115.0 IU/mL). In other hepatic viral markers, HBsAg, anti-HCV, and IgM anti-HEV were all negative; anti-HBs was positive. Autoimmune markers, such as fluorescent antinuclear antibody test, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, and anti-liver/ kidney microsomal antibody were all negative; Immunoglobulin G level slightly exceeded the normal upper limit (

Table 2). Laboratory tests confirmed the presence of severe acute HAV infection accompanied with Graves' disease.

Liver sonography showed normal echogenecity of the liver without focal lesion or ascites. However, diffuse gallbladder wall thickening without gallbladder distention or bile duct dilatation, and several enlarged lymph nodes in hepatic hilum were identified, this in turn suggested secondary findings of acute hepatitis. The most prominent lymph node is indicated by asterisk mark on figure (

Fig. 1). Thyroid sonography demonstrated a moderate enlargement of both lobes of the thyroid gland with heterogeneous parenchymal echogenicity, but there was no abnormal focal lesion.

The patient underwent conservative management, including being given intravenous amino-acid, dextrose fluids, and symptom control. During the follow-up period, high fever had subsided on the third day, and not only the gastroenterological symptoms but also liver function tests showed gradual improvement.

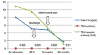

However, thyroid dysfunction was maintained even on the day prior to discharge. Concerning about being in danger of liver failure, taking anti-thyroid drug was planned to defer until improvement of liver function by endocrinology consultation. She was discharged from the hospital at the tenth day along with hepatotonics. After 2 weeks at the second outpatient follow- up, the severity of cholestatic jaundice and high bilirubin levels resolved markedly, total bilirubin from 12.57 mg/dL to 2.42 mg/dL, direct bilirubin from 7.57 mg/dL to 1.12 mg/dL (

Fig. 2). Thyroid function was also partially improved, free T4 from >7.77 ng/dL to 4.80 ng/dL, while TSH level was still maintained at <0.005 µIU/mL. Therefore, she was started on methimazole with a dose of 15 mg twice a day. She had not suffered any serious side effects, and thyrotoxic symptoms had gotten better gradually (

Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, only a few cases of Graves' disease that was triggered by viral hepatitis have been reported in the literature worldwide. However, the number of cases is small and unusual. Even if several cases of HBV, HCV, and recently HEV were demonstrated,

1011121314 we were unable to find any case of HAV in the literature.

There are case reports of patients developing Graves's disease concurrent with HBV and HCV infections, respectively.

1014 Two patients showed marked improvement after conservative treatment, including anti-viral agent or anti-thyroid drug. Antigen mimicry, epitope modification, T-cell activation, or direct invasion of hepatitis virus were suggested as mechanisms inducing Graves' disease.

1114 Actually, Yoffe et al. identified extrahepatic distribution of HBV nucleic acid, i.e. lymph nodes, spleen, kidneys, and thyroid tissue by Southern blot hybridization analysis.

9 This finding can explain the improvement of thyroid function test correlated with clearance of HBV DNA.

In the case of HCV infection, it may not only destroy thyroid tissue directly, but lead to aberrant expression of human leukocyte antigen class II on thyroid cell. Consequentially, it result in activation of autoreactive T cells, then trigger autoimmune thyroiditis.

11

Recently, a few cases of acute HEV triggering the hyperthyroidism have been addressed. There was only one case of autoimmune thyroiditis associated with acute HEV infection in a middle aged healthy woman.

12 Another case report showed that in patients already diagnosed with hyperthyroidism, acute HEV infection provoked thyrotoxicosis.

13 Although it was difficult to elucidate causal relationship between the two diseases, it was surely obvious acute HEV infection might not only trigger new autoimmune thyroid disease, but also provoke flare up in patient with preexisting hyperthyroidism.

To our knowledge, there is one case report of Graves' disease concurrent with acute HAV infection.

15 In that case, the patient already had uncontrolled Graves' disease, after acute HAV infection he showed a fulminant course of viral hepatitis. It was postulated that the high levels of thyroid hormones resulted in increased metabolic stress of hepatocytes, potentiating the hepatotoxic effect of HAV infection. While, our patient is the first case report, in which acute HAV infection is suggested as a possible triggering factor for Graves' disease.

Extrahepatic manifestations of HAV are very rare and are usually immunologically mediated. These include evanescent skin rash, transient arthralgia, arthritis, cryoglobulinemia and cutaneous vasculitis.

16 The mechanism inducing extrahepatic manifestation is almost non-existent until now. Deposition of IgM and complement in extrahepatic tissue was observed in certain case, and this was considered as possible mechanism.

Considering that HAV and HEV are food borne infections, the pathogenesis suggested to explain the extrahepatic manifestations of HEV infection may be possible in HAV infection. The pathogenic mechanisms include direct cytopathic tissue damage by extrahepatic replication or immunological processes induced by a cross-reactive host immune response to hepatitis virus.

17 The autoimmune thyroiditis is rare extrahepatic disease in the context of not only HAV but also HEV infection. The previous observation of acute HAV infection associated with autoimmune hepatitis suggests the possibility that this virus might be a trigger for autoimmune thyroiditis.

18 Hence, we can hypothesize that robust immune reactions during phase of acute HAV infection lead to onset of Graves' disease in susceptible patients who have high titers of thyroid autoantibodies.

Although pre-existing thyroid autoantibodies cannot be completely excluded in our case, we can strongly affirm that HAV infection brings about Graves' disease. The patient never had symptoms suggestive of hyperthyroidism. Besides, thyroid function tests performed previously were normal. Except HAV infection, there was no trigger factor of Graves' disease, such as alleged medication or infectious disease such as Hantaan virus and Epstein-Barr virus.

78

The liver is a major organ responsible for metabolizing the thyroid hormones, as well as for producing thyroid binding proteins, such as thyroid binding globulin, transthyretin, and albumin.

19 Conversely, thyroid hormones play a significant role in the activity of glucoronyltransferase involved in bilirubin metabolism.

20 Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the thyroid function in patients with liver disease and inversely liver function in patients with thyroid disease.

This is the first case report showing the association between Graves' disease and acute HAV infection. Based on evidences like the above, we might be able to infer that acute HAV infection may contribute to the development of Graves' disease. Therefore, in encountering a patient with acute HAV infection, routine thyroid function test should be considered to evaluate concomitant autoimmune thyroid disease.

In this report, we describe the first case of acute HAV infection concurrent with Graves' disease without preexisting thyroid disease. Although several cases of Graves' disease triggered by HBV, HCV, and recently HEV infection have been previously reported, this is indeed a first case linked to HAV infection. An accurate etiology has not been established yet, and is still being studied. However, this case suggests that HAV infection might trigger an autoimmune thyroid disease in susceptible individuals. Therefore, attentive confirmation and monitoring of thyroid function in patients with other viral hepatitis as well as HAV must be required to avoid omission of changeable thyroid autoimmunity. We might be able to give an early diagnosis and initiate proper therapy immediately.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download