1. Djulbegovic B, Kumar A. Multiple myeloma: detecting the effects of new treatments. Lancet. 2008; 371:1642–1644. PMID:

18486726.

2. Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016; 91:719–734. PMID:

27291302.

3. Maybury B, Cook G, Pratt G, Yong K, Ramasamy K. Augmenting autologous stem cell transplantation to improve outcomes in myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016; 22:1926–1937. PMID:

27288955.

4. Raza S, Safyan RA, Rosenbaum E, Bowman AS, Lentzsch S. Optimizing current and emerging therapies in multiple myeloma: a guide for the hematologist. Ther Adv Hematol. 2017; 8:55–70. PMID:

28203342.

5. Reece D, Song K, LeBlanc R, et al. Efficacy and safety of busulfan-based conditioning regimens for multiple myeloma. Oncologist. 2013; 18:611–618. PMID:

23628980.

6. Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:1617–1629. PMID:

26596670.

7. Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:895–905. PMID:

25184862.

8. Sengsayadeth S, Malard F, Savani BN, Garderet L, Mohty M. Posttransplant maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma: the changing landscape. Blood Cancer J. 2017; 7:e545. PMID:

28338672.

9. Fritz E, Ludwig H. Interferon-alpha treatment in multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of 30 randomised trials among 3948 patients. Ann Oncol. 2000; 11:1427–1436. PMID:

11142483.

10. Shustik C, Belch A, Robinson S, et al. A randomised comparison of melphalan with prednisone or dexamethasone as induction therapy and dexamethasone or observation as maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma: NCIC CTG MY.7. Br J Haematol. 2007; 136:203–211. PMID:

17233817.

11. Ludwig H, Durie BG, McCarthy P, et al. IMWG consensus on maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012; 119:3003–3015. PMID:

22271445.

12. McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:1770–1781. PMID:

22571201.

13. Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:1782–1791. PMID:

22571202.

14. Moreau P, Facon T, Attal M, et al. Comparison of 200 mg/m(2) melphalan and 8 Gy total body irradiation plus 140 mg/m(2) melphalan as conditioning regimens for peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: final analysis of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome 9502 randomized trial. Blood. 2002; 99:731–735. PMID:

11806971.

15. Lahuerta JJ, Martinez-Lopez J, Grande C, et al. Conditioning regimens in autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a comparative study of efficacy and toxicity from the Spanish Registry for Transplantation in Multiple Myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2000; 109:138–147. PMID:

10848793.

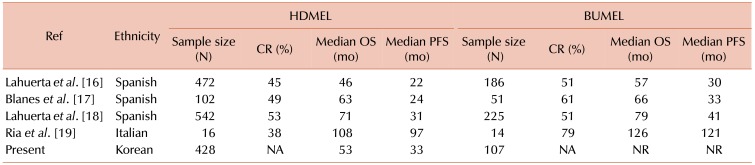

16. Lahuerta JJ, Grande C, Blade J, et al. Myeloablative treatments for multiple myeloma: update of a comparative study of different regimens used in patients from the Spanish registry for transplantation in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002; 43:67–74. PMID:

11908738.

17. Blanes M, Lahuerta JJ, González JD, et al. Intravenous busulfan and melphalan as a conditioning regimen for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a matched comparison to a melphalan-only approach. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013; 19:69–74. PMID:

22897964.

18. Lahuerta JJ, Mateos MV, Martínez-López J, et al. Busulfan 12 mg/kg plus melphalan 140 mg/m2 versus melphalan 200 mg/m2 as conditioning regimens for autologous transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients included in the PETHEMA/GEM2000 study. Haematologica. 2010; 95:1913–1920. PMID:

20663944.

19. Ria R, Falzetti F, Ballanti S, et al. Melphalan versus melphalan plus busulphan in conditioning to autologous stem cell transplantation for low-risk multiple myeloma. Hematol J. 2004; 5:118–122. PMID:

15048061.

20. Kim DS. Introduction: health of the health care system in Korea. Soc Work Public Health. 2010; 25:127–141. PMID:

20391257.

21. Kim SD, Lee JH, Hur EH, et al. Influence of GST gene polymorphisms on the clearance of intravenous busulfan in adult patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011; 17:1222–1230. PMID:

21215809.

22. Chiesa R, Cappelli B, Crocchiolo R, et al. Unpredictability of intravenous busulfan pharmacokinetics in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for advanced beta thalassemia: limited toxicity with a dose-adjustment policy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010; 16:622–628. PMID:

19963071.

23. Hahn T, Zhelnova E, Sucheston L, et al. A deletion polymorphism in glutathione-S-transferase mu (GSTM1) and/or theta (GSTT1) is associated with an increased risk of toxicity after autologous blood and marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010; 16:801–808. PMID:

20074657.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download