Dear Editor:

Morphea is an autoimmune disease characterized by sclerosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Its clinical findings are diverse, ranging from erythematous to hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or plaques1. Due to this variability, morphea may be misdiagnosed especially by non-dermatologists as pigmentary disorders such as vitiligo2. We report a case of a patient with generalized morphea who was delayed from receiving proper treatments due to misdiagnosis as vitiligo at a local oriental clinic.

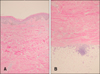

A 29-year-old male presented with multiple hypopigmented and hyperpigmented sclerotic plaques surrounded by violaceous erythematous borders on his whole body (Fig. 1). For 2 years at a local oriental medical clinic, he had been treated with unidentified local injections, named ‘yakchim’ or pharmacupunctures, and phototherapy under the impression of vitiligo, and was referred when his symptoms worsened, seeking further treatments such as epidermal grafts. Skin biopsy revealed thickened and sclerotic collagen bundles in the reticular dermis (Fig. 2), with direct immunofluorescence study showing weak linear positivity of IgM in dermoepidermal junction, suggesting scleroderma. Neither sclerodactyly nor Raynaud phenomenon were observed, leading to the impression of generalized morphea. With methotrexate and steroid pulse therapy, the disease progression has ceased, but due to the late diagnosis, permanent sclerotic changes remained in addition to contracture of his right ankle. Localized scleroderma skin damage index (LoSDI), which evaluates the overall disease severity and sequelae3, was 35. LoSDI includes the sum of four skin damage scores (dermal atrophy, subcutaneous atrophy, pigmentary change, and central thickness) which ranges from 0 to 2163. In a recent large-scale study, the mean LoSDI score in adult morphea was about 17.3, so our patient's score is considerably high although the established cut-off to define ‘severe stage’ is still unavailable.

Due to the diverse cutaneous manifestation of morphea, it may be misdiagnosed, and a study in children found a mean duration of 11.1 months before the correct diagnosis, with various impressions of atopic dermatitis, infection, and vitiligo by general practitioners2. Late diagnosis would lead to delayed treatment and increased risks of complications including dermis and fat atrophy, contracture, and limb length discrepancy1. Likewise, contracture of the right foot and widespread sclerotic cutaneous lesions developed in our patient, posing a therapeutic challenge.

The patient initially visited an oriental medical clinic and had been misdiagnosed and treated for two years. Oriental medicine is widely used in Korea, yet it still remains largely unconfirmed, which may cause various unpredictable adverse events (AEs). In a survey, 12% of the Korean population responded that they had suffered from an AE associated with oriental medicine, with over 50% of the AEs caused either by misdiagnosis or herbal toxicities4. In addition to delayed diagnosis and systemic AEs by herbal medicines, various local AEs such as secondary bacterial or atypical mycobacterial infections, scars, and dystrophic calcinosis cutis by acupuncture have been also reported5. Considering these complications, a thorough review of the patients' past histories of oriental medicine is obligatory.

The patient in the current case would have had less permanent deformities if a correct diagnosis was made earlier. Understanding the variability of the cutaneous manifestations of morphea is essential to prevent irreversible functional and aesthetic complications. The possibility of misdiagnosis and unpredictable AEs is likely to be higher with general practitioners, thus the general population should be informed of the need to be examined by dermatologists, especially when skin lesions are extensive or chronic.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Fett N. Scleroderma: nomenclature, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013; 31:432–437.

2. Weibel L, Laguda B, Atherton D, Harper JI. Misdiagnosis and delay in referral of children with localized scleroderma. Br J Dermatol. 2011; 165:1308–1313.

3. Condie D, Grabell D, Jacobe H. Comparison of outcomes in adults with pediatric-onset morphea and those with adult-onset morphea: a cross-sectional study from the morphea in adults and children cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014; 66:3496–3504.

4. Shin HK, Jeong SJ, Lee MS, Ernst E. Adverse events attributed to traditional Korean medical practices: 1999-2010. Bull World Health Organ. 2013; 91:569–575.

5. Lee SJ, Yeo IK, Park KY, Kim YK. Three cases of adverse effects following the acupuncture in oriental medical clinic. Korean J Dermatol. 2013; 51:189–191.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download