Abstract

Purpose

Methods

Results

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Chemoprophylaxis and pneumococcal vaccination status by year at diagnosis. As there have been no cases of invasive bacterial infection since 2008, asplenic children were divided into two groups by diagnosed year, respectively: ones who were diagnosed with asplenia between 1997 and 2007 and the others who were diagnosed with asplenia between 2008 and 2016. The rate of chemoprophylaxis was 10.2% (13/127) among children who were diagnosed with asplenia between 1997 and 2007, but 30.2% (26/86) were received chemoprophylaxis among those who were diagnosed between 2008 and 2016. Similarly, in pneumococcal vaccination, 22.6% (19/84) were vaccinated completely among children who were diagnosed with asplenia between 1997 and 2007, but 58.3% (49/84) were vaccinated completely among those who were diagnosed between 2008 and 2016.

Table 1

Characteristics of Children with Acquired, Congenital, or Functional Asplenia

Values are presented as number (%) or median (range).

*The most common cause of splenectomy was hereditary spherocytosis (n=16, 39.0%) followed by idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (n=11, 26.8%), splenic disease (n=6, 14.6%), trauma (n=5, 12.2%), and others (n=2, 4.9%). Three out of six patients with splenic disease had a splenic cyst, two had splenic infarction and one had splenic torsion. One out of others was pancreatitis and the other was secondary splenomegaly by portal vein thrombosis.

†Being received prophylactic antibiotics at least 12 months among patients who observed for 12 months or longer.

Abbreviations: CCHD, complex congenital heart disease; NA, not applicable.

Table 2

Characteristics of Episodes of Invasive Bacterial Infection in Patients with Asplenia

*Immunization status at infection.

Abbreviations: Pnc, pneumococcal conjugate or polysccharide vaccine; Hib, Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine; Mnc, meningococcal vaccine; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; BA, biliary atresia; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; IAA, interruption of aortic arch; TGA, transposition of great arteries; PA, pulmonary atresia; DORV, double outlet of right ventricle; TAPVR, total anomalous of pulmonary venous return.

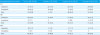

Table 3

Vaccination Status of Asplenic Children against Encapsulated Bacteria

Values are presented as number (%).

*Pnc: 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine or protein-conjugate vaccine against Streptococcus pneumoniae.

†Hib: Protein-conjugate vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae type B.

‡Mnc: Protein-conjugate vaccine against Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A, C, W-135, and Y.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download