Dear Editor:

Cutaneous aspergillosis is an opportunistic fungal infection caused by Aspergillus species, which is usually caused by its direct inoculation at a site of skin injury, such as that induced by surgery, burn, or trauma1. Laser tattoo treatment using Q-switched lasers is the gold standard for tattoo removal2. Although tattooing has various complications, including infection, allergic reaction, and localized skin diseases, no infectious complications of laser tattoo removal have been reported. We present a rare complication of laser tattoo removal, primary cutaneous aspergillosis.

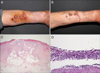

A 77-year-old previously healthy Korean man presented with multiple ulcers on both forearms (Fig. 1A). He had tattoos on his both arms for 50 years. One month previously, he had the tattoos removed by three sessions at 6-week interval of Q-switched 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser treatment at local dermatologic clinic. On the treated sites, he was recommended to apply mupirocin ointment. After the third session, multiple ulcers with purulent discharge developed at the laser-treated sites. The lesions were painful and itchy. An excisional biopsy of the largest ulcer was performed. Considering an infectious condition, cefadroxil (500 mg twice daily) was prescribed for 2 weeks. However, the lesions had not improved markedly at the follow-up visit. No organisms grew in bacterial, acid-fast bacillus (AFB) and fungal cultures of the tissue. A cutaneous biopsy showed ulceration and partial necrosis of dermal collagen accompanied by diffuse lymphohistiocytic infiltration (Fig. 1C). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining showed many septate fungal hyphae with dichotomous branching, which is compatible with cutaneous aspergillosis (Fig. 1D). After 4 weeks of itraconazole (100 mg twice daily), and the lesions improved dramatically (Fig. 1B). To determine the causative organism, histological samples were investigated using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). DNA was extracted from the samples using a DNA prep kit (BIOFACT, Daejeon, Korea). Oligonucleotide primers used to detect all fungi generically and Aspergillus specifically were designed from known sequences3. PCR was performed to identify fungal Aspergillus-specific and A. fumigatus-specific DNA (Fig. 2).

Laser tattoo removal using Q-switched lasers is generally considered safe. In one of the largest studies of laser tattoo removal, Bencini et al.4. reported that 93.8% (330/352) of the patients underwent the procedure without adverse effects. To our knowledge, no infectious complication associated with laser tattoo removal has been reported. An accurate diagnosis is important when aspergillosis is suspected. Diagnostic methods include microscopic examination, culture, and PCR5. The microscopic examination or the fungal culture has low sensitivity and cannot be performed using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. PCR assays have the highest sensitivity and specificity, and the rapidity and accuracy of PCR enable earlier diagnosis and identification of the fungus at the species level. The advantage of PCR assays is that either FFPE tissue or fresh specimens can be used.

In conclusion, our case shows that primary cutaneous aspergillosis can occur in an immunocompetent patient after tattoo removal using a Q-switched laser. Physicians should be aware of this unexpected complication. Careful post-laser wound care must be performed after laser tattoo removal. A PCR assay could be helpful for early diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Multiple ulcerations of the forearm at initial presentation. Yellow color is due to application of povidone iodine solution. (B) Two weeks after treatment with oral itraconazole. (C) Perivascular and diffuse inflammatory cell infiltration with epidermal ulceration and dermal collagen necrosis (H&E, ×40). (D) Fungal hyphae are septate and branch dichotomously at acute angles, which is typical of Aspergillus species (Periodic acid-Schiff [PAS], ×200). |

References

1. Bernardeschi C, Foulet F, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Ortonne N, Sitbon K, Quereux G, et al. Cutaneous invasive aspergillosis: retrospective multicenter dtudy of the french invasive-aspergillosis registry and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94:e1018.

2. Luebberding S, Alexiades-Armenakas M. New tattoo approaches in dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2014; 32:91–96.

3. Luo G, Mitchell TG. Rapid identification of pathogenic fungi directly from cultures by using multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:2860–2865.

4. Bencini PL, Cazzaniga S, Tourlaki A, Galimberti MG, Naldi L. Removal of tattoos by q-switched laser: variables influencing outcome and sequelae in a large cohort of treated patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012; 148:1364–1369.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download