This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

A prolonged-release formulation of oxycodone/naloxone has been shown to be effective in European populations for the management of chronic moderate to severe pain. However, no clinical data exist for its use in Korean patients. The objective of this study was to assess efficacy and safety of prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone in Korean patients for management of chronic moderate-to-severe pain.

Methods

In this multicenter, single-arm, open-label, phase IV study, Korean adults with moderate-to-severe spinal disorder-related pain that was not satisfactorily controlled with weak opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs received prolonged-release oral oxycodone/naloxone at a starting dose of 10/5 mg/day (maximum 80/40 mg/day) for 8 weeks. Changes in pain intensity and quality of life (QoL) were measured using a numeric rating scale (NRS, 0–10) and the Korean-language EuroQol-five dimensions questionnaire, respectively.

Results

Among 209 patients assessed for efficacy, the mean NRS pain score was reduced by 25.9% between baseline and week 8 of treatment (p < 0.0001). There was also a significant improvement in QoL from baseline to week 8 (p < 0.0001). The incidence of adverse drug reactions was 27.7%, the most common being nausea, constipation, and dizziness; 77.9% of these adverse drug reactions had resolved or were resolving at the end of the study.

Conclusions

Prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone provided significant and clinically relevant reductions in pain intensity and improved QoL in Korean patients with chronic spinal disorders. (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT01811238)

Go to :

Keywords: Spine, Chronic pain, Analgesia, Oxycodone naloxone combination

Chronic pain related to spinal disorders is a common and important clinical issue in many adult populations.

12) A nationally-representative Korean survey conducted in 2007 estimated that over 5.5 million Korean adults had ever experienced back pain (around 15% of those aged 20–89 years); furthermore, an estimated 37% of these individuals suffered from chronic back pain (> 3 months' duration).

3) In a cross-sectional study of patients undergoing computed tomography scans for issues unrelated to spinal disorders, approximately 36% of patients reported back pain lasting for at least 1 month.

4)

Adequate management of chronic pain is important to reduce its impact on many aspects of daily living, including work activity, sleep, mood, and quality of life (QoL).

567) There is evidence showing that individuals who achieve good pain control benefit substantially in terms of improved work activity, functioning, and QoL, and experience less depression and fatigue.

5)

Nonopioid analgesics are usually the first treatment option for mild to moderate chronic non-cancer pain, while opioid analgesics are considered effective for managing severe chronic pain that is difficult to control using nonopioid therapies.

89) Indeed, the use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain, such as back pain, spinal osteoarthritis, and failed back surgery, has increased in recent years.

1011) Recommended pharmacotherapies based on the American College of Physicians/American Pain Society guidelines

12) include acetaminophen, benzodiazepine, tramadol, and opioids for both subacute and chronic back pain.

Opioids are considered effective for management of nociceptive pain and moderately effective for neuropathic pain. However, certain adverse effects, such as constipation, nausea, and vomiting, can limit the use of opioids in clinical practice. Opioid-associated constipation is among the most common and bothersome of these adverse effects, and can reduce QoL for patients.

13) A prolonged-release (PR) formulation combining oxycodone, an opioid analgesic, with naloxone, a peripherally acting opioid antagonist, is associated with a lower incidence of constipation than oxycodone alone.

141516) Naloxone binds to µ opioid receptors in the gut wall with an affinity higher than that of oxycodone, thereby preventing oxycodone from exerting an effect on the gastrointestinal system, and reducing the risk of constipation. Owing to its low oral bioavailability, naloxone has no effect on opioid receptors in the central nervous system and therefore does not affect the analgesic properties of oxycodone.

17)

In Korea, use of opioids has increased markedly because of heightened awareness of the need for adequate pain control on the part of both physicians and patients.

101819) This trend has been studied widely in the context of cancer pain, but few studies have included patients with non-cancer pain. A PR formulation of oxycodone/naloxone was approved in Korea in 2009 for the management of chronic moderate to severe cancer pain and non-cancer pain. Although there are extensive data from clinical trials of oxycodone/naloxone in European populations,

141516) no clinical data exist for its use in Korean patients. The objective of the present study was to assess the efficacy and safety of PR oxycodone/naloxone in Korean patients with chronic moderate to severe pain attributable to a spinal disorder, that was not adequately controlled with weak opioids and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

This study was an 8-week, single-arm, open-label, interventional, phase IV trial conducted in 10 centers in Korea between 26 September, 2012 and 2 August, 2013 (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT01811238). An Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation, and Korean Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before participation.

Korean adults aged ≥ 20 to < 80 years were eligible for inclusion in the study if they had experienced chronic moderate to severe pain (pain score ≥ 4 on a numeric rating scale [NRS] ranging from 0 [no pain] to 10 [very severe pain]) from a spinal disorder for at least 3 months that was not satisfactorily controlled with analgesics (weak opioids or NSAIDs). Patients were either opioid-naïve or had not received strong opioid treatment (including oxycodone/naloxone) within 4 weeks of screening.

Key exclusion criteria were: pain with a nonspinal cause; major surgery within 1 month of screening or planned surgery during the study period; uncontrolled constipation; severe respiratory depression due to hypoxia and/or hypercapnia; moderate to severe hepatic impairment; and clinically significant impairment of cardiovascular, respiratory, or renal function. Patients were also excluded if they were receiving anticancer treatment for nonmalignant or malignant tumours, or any treatment that could affect pain measurements.

Interventions

Patients received oxycodone/naloxone (Targin; Mundipharma Korea Ltd., Seoul, Korea) PR tablets at a starting dose of 5/2.5 mg administered twice daily for 8 weeks. The dose could be uptitrated to 10/5 mg, 20/10 mg, or 40/20 mg twice daily at the discretion of the investigator. The criteria for uptitration were as follows: use of analgesic rescue medication (immediate-release oxycodone hydrochloride 5 mg) on average ≥ 2 times per day (i.e., ≥ 10 mg/day); worsening NRS pain score compared with the previous visit; or any other reason considered appropriate by the investigator.

Analgesics used continuously and at a stable dose prior to the study were permitted as concomitant medications if the investigator deemed that these would not affect the study results. If patients were receiving medications that could induce additional central nervous system depression when taken with oxycodone/naloxone (e.g., opioid antagonists, hypnotics, or central nervous system depressants), they had to be assessed and could be withdrawn from the study at the investigator's discretion. Prescription of laxatives was permitted as required during the study. Strong opioids (e.g., buprenorphine, morphine) and new prescriptions of analgesics (other than the study drugs) were not permitted during the study.

Outcome Measures

Efficacy

The primary outcome was the change in pain intensity as measured on the NRS between baseline and week 8 of treatment. Patients were asked to rate their average pain intensity score over the 24 hours prior to the visit. Investigators provided assessments of overall satisfaction with treatment at baseline and weeks 1, 4, and 8.

Secondary outcomes included the change from baseline in pain intensity score at week 4 of treatment and the change from baseline in QoL, measured using a Korean language version of the EuroQol-five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D)

2021) and the EQ-visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) at week 8 of treatment. The EQ-5D covers the domains of mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, with each item being scored on a 3-point scale from 1 (no problems) to 3 (inability/extreme problems). The EQ-VAS enables patients to rate their overall health status on the day of each visit on a scale from 0 (worst imaginable) to 100 (best imaginable).

Safety

Safety assessments included reports at any time (including during each study visit) of adverse events, serious adverse events, and adverse drug reactions, defined as reactions for which a causal relationship with the study drug could not be ruled out. Clinical laboratory tests were performed at baseline and at week 8. A physical examination including measurement of vital signs was performed at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, and 8.

Statistical Analyses

Efficacy data were analysed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) sets. The ITT set included patients who had received ≥ 1 dose of study drug and had data available for ≥ 1 primary efficacy endpoint. The PP set included patients in the ITT set who had completed the study according to the protocol. Paired t-tests were used to analyse changes in the NRS score from baseline to week 8 (primary outcome) or week 4 (secondary outcome) and differences between baseline and week 8 in the EQ-5D total score.

The safety set included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. Changes in clinical laboratory tests and vital signs between baseline and week 8 were analysed using paired t-tests. Changes in clinical laboratory test results and findings on physical examination from baseline to week 8 were summarized by frequency and percentage, and the predose and postdose measurements were compared using McNemar's test. The last observation carried forward method was used for missing data or patients withdrawn during the study.

Sample Size

Based on data from a previous study of patients with low back pain or osteoarthritis pain,

22) the sample size needed to achieve a significance level of 0.05 for the primary end-point was 189 patients. Assuming a 20% dropout rate, the aim was to enroll 237 patients into the study.

Go to :

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

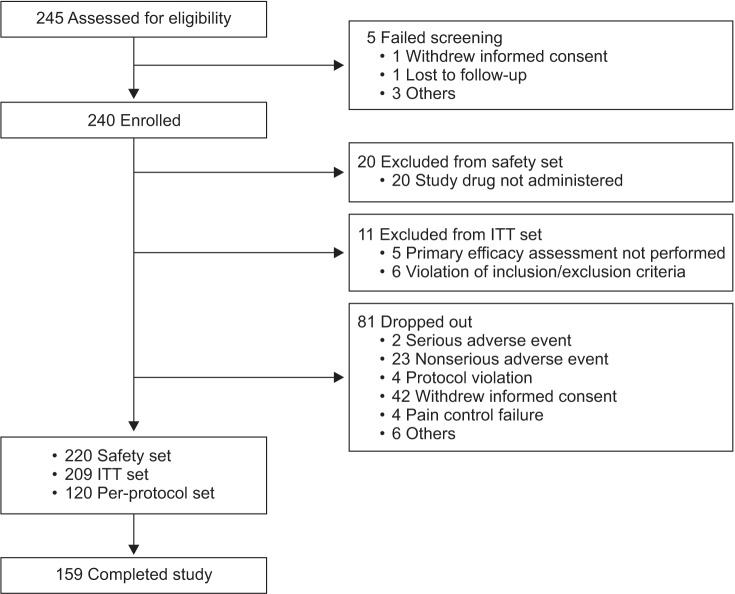

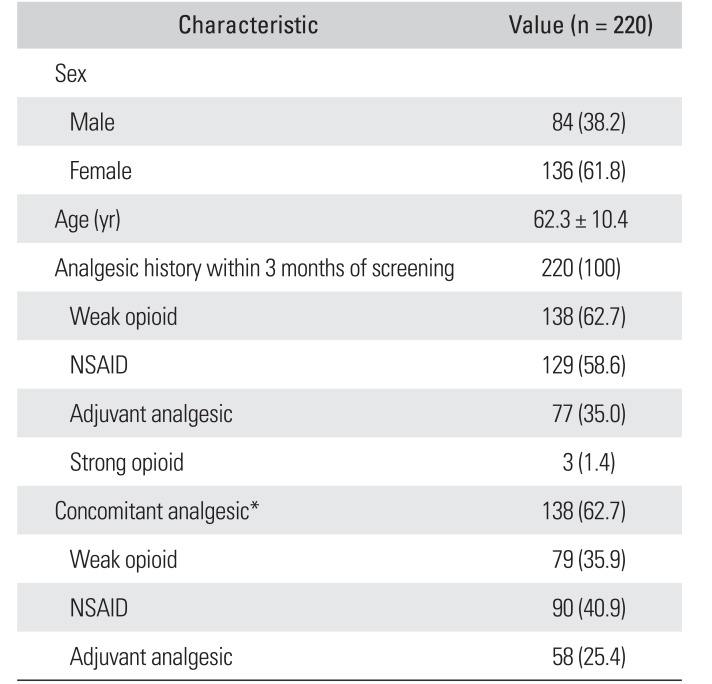

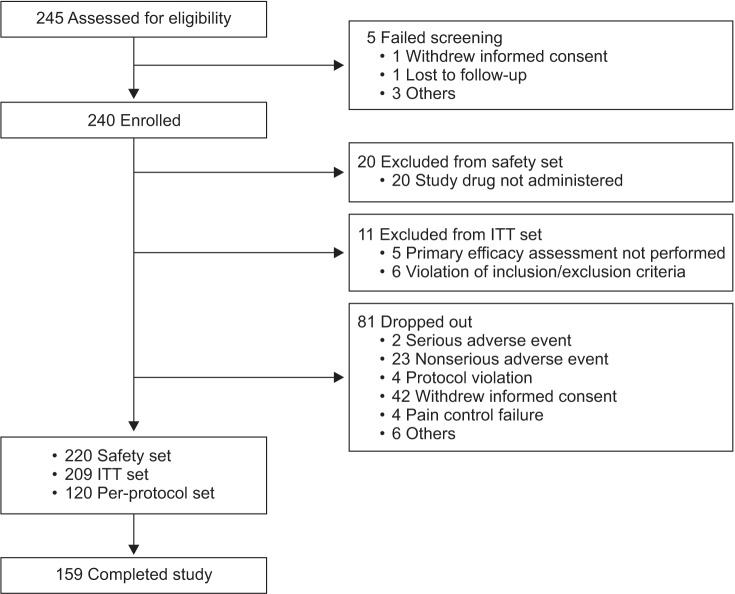

Of the 240 patients enrolled, 220 were included in the safety set and 209 in the ITT set (

Fig. 1). The mean ± standard deviation (SD) patient age in the safety set was 62.3 ± 10.4 years, and 61.8% of the patients were female (

Table 1). The study included patients with persistent or unresolved pain for ≥ 3 months from spinal disorders including (but not limited to) lumbar disc herniation, spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, internal disc disruption, cervical disc herniation, cervical myelopathy, osteoporotic vertebral fracture, persistent postoperative back pain, spinal fracture, degenerative disc disease, spinal deformity, and spinal cord injury. In these patients, the pain caused by the original condition did not resolve and resulted in persistent pain; therefore, they were considered eligible for the study. Eighty-three patients (37.7%) had a history of surgery within 3 years of the start of the study; 53 of these patients (24.1%) had a history of surgery related to a spinal disorder.

| Fig. 1Patient disposition. ITT: intention-to-treat.

|

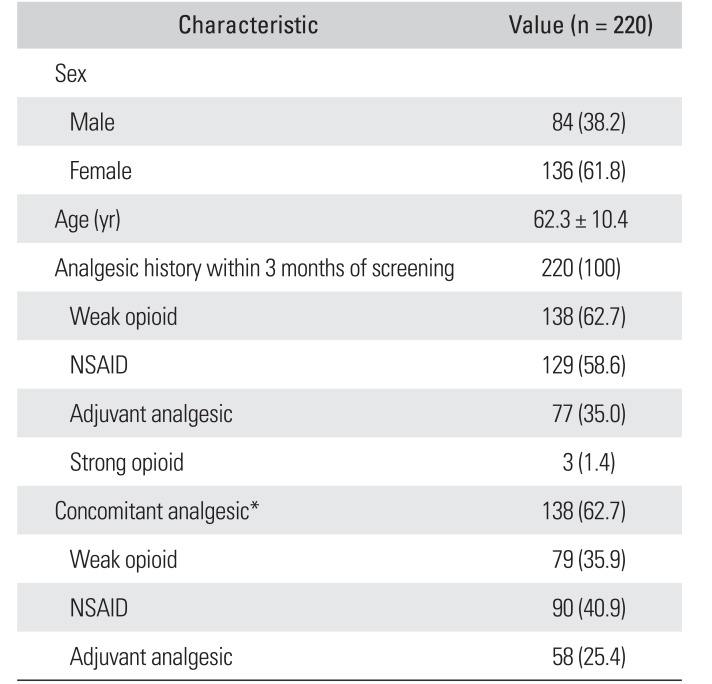

Table 1

Baseline Demographics, Patient Characteristics, and Medication Use (Safety Set)

|

Characteristic |

Value (n = 220) |

|

Sex |

|

|

Male |

84 (38.2) |

|

Female |

136 (61.8) |

|

Age (yr) |

62.3 ± 10.4 |

|

Analgesic history within 3 months of screening |

220 (100) |

|

Weak opioid |

138 (62.7) |

|

NSAID |

129 (58.6) |

|

Adjuvant analgesic |

77 (35.0) |

|

Strong opioid |

3 (1.4) |

|

Concomitant analgesic*

|

138 (62.7) |

|

Weak opioid |

79 (35.9) |

|

NSAID |

90 (40.9) |

|

Adjuvant analgesic |

58 (25.4) |

All patients in the safety set had a history of receiving analgesic medication within 3 months of the screening visit (

Table 1). The majority of patients (n = 141, 64.1%) had previously used opioids. Most patients (n = 138, 62.7%) continued to take concomitant permitted analgesics (

Table 1).

Oxycodone/Naloxone Dose and Use of Analgesic Rescue Medication

Among the 220 patients in the safety set, the daily dose of PR oxycodone/naloxone at week 8 was (mean ± SD, 18.2 ± 10.2 mg). For the 159 patients who completed the study, the dose of PR oxycodone/naloxone at the final visit was 10/5 mg twice daily for 68 patients (42.8%), 5/2.5 mg twice daily for 67 patients (42.1%), 20/10 mg twice daily for 23 patients (14.5%), and 40/20 mg twice daily for one patient (0.6%). During the study, 124 patients (56.4%) in the safety set required at least one dose of analgesic rescue medication.

Efficacy

Pain

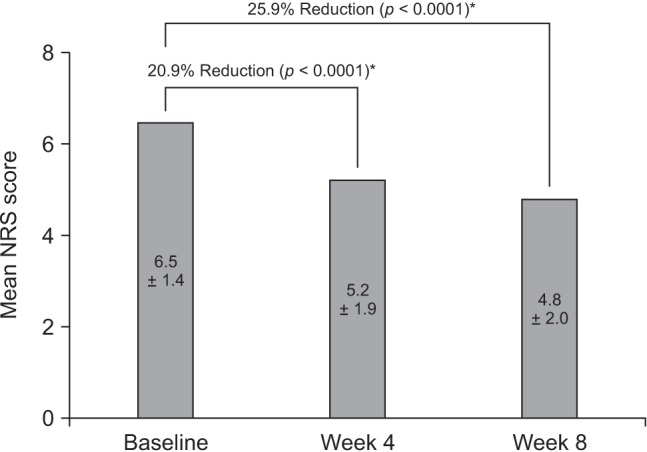

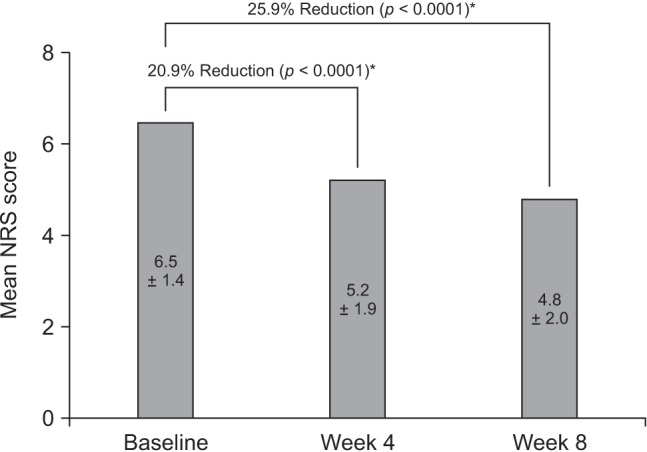

In the ITT set, the overall mean NRS pain score decreased significantly from 6.5 ± 1.4 at baseline to 4.8 ± 2.0 at week 8 (mean ± SD difference, −1.7 ± 2.2; −25.9%;

p < 0.0001) (

Fig. 2). The reduction in NRS pain score from baseline to week 4 was also statistically significant (mean ± SD change, −1.3 ± 2.0; −20.9%;

p < 0.0001) (

Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2The plot shows mean pain intensity score (numeric rating scale [NRS]) at baseline and at weeks 4 and 8. The values shown in each bar represent the mean ± standard deviation score. *Statistically significant changes in pain intensity scores were observed after treatment with the study drug.

|

In an analysis of NRS scores in the PP set, the mean score was 6.6 ± 1.4 at baseline and 4.4 ± 2.0 at week 8, representing a change of −2.2 ± 1.9 (33.7%, p < 0.0001); the reduction was statistically significant and greater than that in the ITT set.

Quality of life

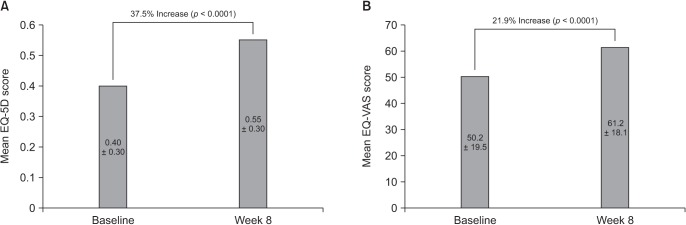

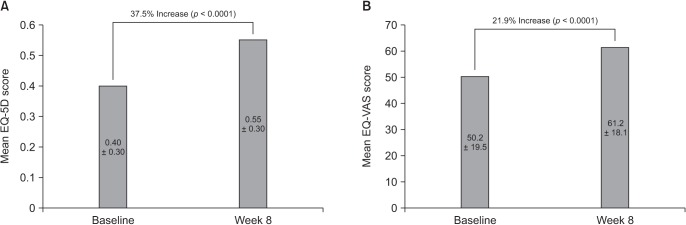

In the ITT set, there was a 37.5% improvement in the mean EQ-5D score (an increase of 0.2 ± 0.4) from baseline to week 8, which was highly significant (

p < 0.0001) (

Fig. 3A). Assessment of health status on the day of each visit, measured using the EQ-VAS, also demonstrated a significant improvement from baseline to week 8 (

p < 0.0001) (

Fig. 3B).

| Fig. 3The plot shows mean scores at baseline and at week 8 for EuroQol-five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D, A) and EQ-visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS, B). The values shown in each bar represent the mean ± standard deviation score.

|

Analysis of EQ-5D scores in the PP set demonstrated a mean change from baseline to week 8 of 0.2 ± 0.4, representing an increase of 52.5% (p < 0.0001). In the PP set, the mean change in EQ-VAS score from baseline to week 8 was 13.9 ± 23.0 (27.2%, p < 0.0001).

Safety

In the safety set, a total of 120 adverse events were reported in 77 patients (35.0%); 95 of these events, reported in 61 patients (27.7%), were deemed to be adverse drug reactions, the most common of which were nausea (9.1%), dizziness (5.5%), and constipation (5.5%) (

Table 2). The majority of adverse events occurred within 1 week of treatment with the study drug. Forty-four adverse events were reported in 30 patients (13.6%) and 38 adverse drug reactions were reported in 26 patients (11.8%).

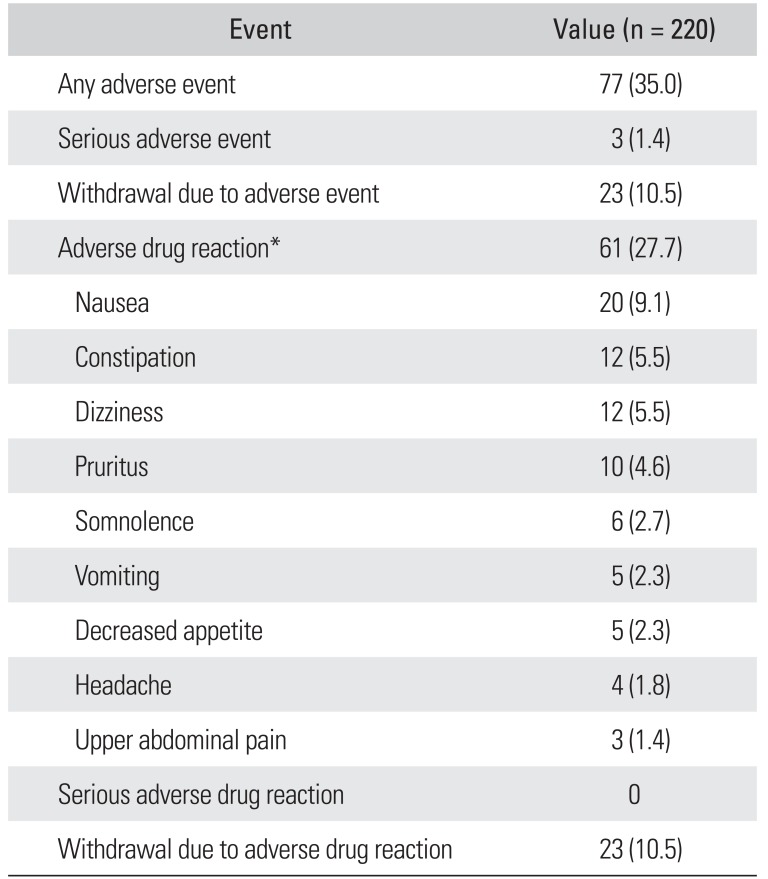

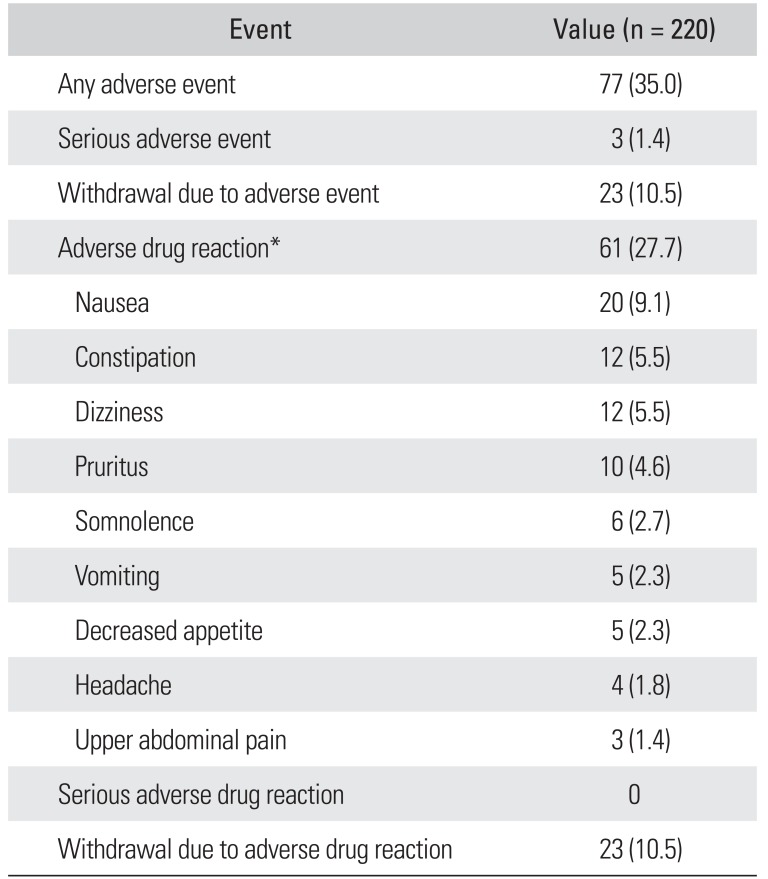

Table 2

Adverse Events and Adverse Drug Reactions Reported During the Study (Safety Set)

|

Event |

Value (n = 220) |

|

Any adverse event |

77 (35.0) |

|

Serious adverse event |

3 (1.4) |

|

Withdrawal due to adverse event |

23 (10.5) |

|

Adverse drug reaction*

|

61 (27.7) |

|

Nausea |

20 (9.1) |

|

Constipation |

12 (5.5) |

|

Dizziness |

12 (5.5) |

|

Pruritus |

10 (4.6) |

|

Somnolence |

6 (2.7) |

|

Vomiting |

5 (2.3) |

|

Decreased appetite |

5 (2.3) |

|

Headache |

4 (1.8) |

|

Upper abdominal pain |

3 (1.4) |

|

Serious adverse drug reaction |

0 |

|

Withdrawal due to adverse drug reaction |

23 (10.5) |

One unexpected adverse drug reaction (mild pollakiuria) was reported; this did not warrant a change in the dose of the study drug and resolved after 1 month. Most of the adverse drug reactions were mild (72 events, 75.8%) and had resolved (54.7%) or were resolving (23.2%) at the end of the study period.

Three serious adverse events (fracture of the femur, osteoarthritis, and renal cancer) occurred in three patients (1.4%), but no causal relationship with the study drug was found. Twenty-three patients (10.5%) withdrew from the study because of adverse drug events; 36 events occurred in these patients. No clinically significant changes in clinical laboratory and blood chemistry tests or vital signs were observed.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first in a Korean population to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of PR oxycodone/naloxone in the treatment of chronic moderate to severe pain associated with a spinal disorder and unsatisfactorily controlled by weak opioids and NSAIDs. Over 8 weeks of treatment, PR oxycodone/naloxone effectively reduced pain intensity, improved QoL, and was well tolerated in these patients.

Our study found a statistically significant reduction in mean pain intensity score of 1.7 points, representing a decrease of almost 26% after 8 weeks of treatment with PR oxycodone/naloxone (ITT set). This reduction of 1.7 points on the NRS for pain intensity corresponds to “much improved” or “very much improved” pain, and reductions in pain intensity of 10%–20% are considered to reflect minimally important changes.

2324) The reduction in pain intensity score was greater in patients in the PP set (2.2 points, representing a 34% decrease). Analysis of the clinical importance of changes in pain intensity in a group of patients with chronic non-cancer pain (mean baseline NRS score 5.9) treated for 12 weeks with duloxetine indicated that a reduction of 34% in pain intensity score was clinically important.

25) However, the magnitude of clinically important change in pain intensity may differ between the individual patient level and the group level, and should be considered alongside the other benefits of treatment, such as tolerability.

23)

Of note in our study was the effective pain control achieved using relatively low doses of oxycodone/naloxone; the majority of patients received the lowest dosage of 10/5 mg/day or the second lowest dosage of 20/10 mg/day. In this regard, the present formulation of oxycodone/naloxone offers a new low-dose option for Korean patients and may be particularly useful when starting therapy.

Quality of life, measured using the EQ-5D, improved by almost 38% over the 8 weeks of treatment with oxycodone/naloxone, while patients' health status on the day of each study visit, measured using the EQ-VAS, improved significantly by almost 22% over the same period. Although the prespecified analysis in our study only included overall QoL assessment, it would also be clinically meaningful to explore which dimensions of QoL were most improved. Our findings are consistent with those of a previous study in which patients treated with oxycodone alone were switched to oxycodone/naloxone because of symptoms of opioid-induced constipation. After 12 weeks of treatment, patients experienced a significant improvement in QoL.

26)

Of the 220 patients in our study who received at least one dose of oxycodone/naloxone, almost 28% reported adverse drug reactions, the most common of which were nausea, dizziness, constipation, and pruritus. There was one unexpected adverse drug reaction, i.e., pollakiuria. Constipation is the most common opioid-induced adverse event reported in patients receiving chronic opioid treatment and negatively impacts overall health-related QoL.

13) In our study, 5.5% of patients reported constipation, which is much lower than the rate of ≥ 15% reported for chronic opioid use in literature reviews and meta-analyses.

272829) The incidence of constipation in a randomized placebo-controlled and active-controlled study of oxycodone/naloxone was 8.4%,

16) somewhat higher than in our study. We note that these observations, which were based on adverse events reporting in our study, do not permit direct conclusions to be made about reduction or prevention of constipation with oxycodone/naloxone. To directly address constipation, it would be desirable to perform a parallel-group comparison of oxycodone/naloxone with oxycodone alone, and to assess constipation symptoms using a specific tool.

As this was a single-arm study without a placebo or active-control group, care should be taken when interpreting the degree of improvement attributable to the test treatment. Another limitation of the present study was its short duration, which precluded assessment of the longer-term efficacy and safety of oxycodone/naloxone in this population.

In this study, Korean patients with chronic pain from spinal disorders receiving a PR oral formulation of oxycodone/naloxone twice daily had statistically significant and clinically relevant reductions in pain intensity and experienced improved QoL after 8 weeks of treatment. Furthermore, PR oxycodone/naloxone demonstrated a favourable safety profile in these patients, with few requirements for dose reduction because of adverse drug reactions, including gastrointestinal effects. PR oxycodone/naloxone may be particularly useful for patients with or at risk of bowel dysfunction who require effective pain control.

30) Consequently, PR oxycodone/naloxone may improve the acceptability of opioid analgesics as a treatment for chronic non-cancer pain.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download