Abstract

Purpose

Recently a controversy has arisen about so-called “ghost surgery” practices, and people have voiced their opinions for legal sanction against such practices, which clearly undermine the foundation of medical ethics. However, there has been a lack of legal basis for punishing those actions. The present study aims to examine which pre-existing legal provisions could be applied to regulate ghost surgery.

Methods

The Korean Medical Service Act has a provision relating to informed consent to inhibit ghost surgery but does not include penalty provisions prohibiting ghost surgery itself. Also, the Korean Supreme Court precedents on this issue have not been settled as of yet. Therefore, this study referred to U.S precedents, law books, and related papers.

Results

With respect to ghost surgery, we expect the charges of bodily harm, assault and battery, and fraud could be applied under Korean law, in addition to charges regarding the violation of medical law, such as the omission of entries or false entries in medical records. A patient provides consent to bodily harm prior to surgery, and only the person who is entrusted with such permission can become the operating surgeon in the operating room.

Conclusion

In other words, even if other medical professionals are present in the operating room, the operating surgeon who received consent must take overall responsibility for the whole process of the surgery. A surgeon should bear in mind that a violation of such duty can constitute a criminal offense.

Recently, Korean media has covered a series of incidents where a surgeon who was not agreed to as the operating surgeon operated on a patient while the patient was under anesthesia [1]. Although this issue has recently got media attention, the general opinion is that the practice of performing surgery on another surgeon's patient, namely ghost surgery, is not a recent development. Ghost surgery is not just limited to the cosmetic surgery field but also secretly performed in other fields of clinical medicine, and it happens in university-affiliated hospitals as well as private hospitals [2]. There has been growing criticism of ghost surgery and a public consensus has been reached regarding the need for punishment. However, although ghost surgery is apparently an act of undermining medical ethics at its core, there are no legal grounds to stop such activity in Korea as of yet. As there exist neither applicable law nor court precedents rendered in relation to ghost surgery, there are conflicting opinions regarding which criminal liabilities should be placed on the surgeon performing ghost surgery. Therefore, this study aims to review the laws and regulations applicable to ghost surgery and the requirements for their application.

As the Korean Medical Service Act was revised recently, the duty of explanation was enshrined in paragraph 1 of article 24. According to this article, a doctor must explain the procedure and receive informed consent from patient in cases of surgery, blood transfusion, and general anesthesia, which may cause serious damage to life or body. Especially, the doctor is required to notify the name of the main surgeon who is to participate in the operation. In other words, ghost surgery can be prevented by letting patients know the name of the surgeon who is performing the surgery when the operation is being explained. Surgeons who breach this confidence will be fined. However, the current definition punishes the negligence of duty of explanation, not ghost surgery itself, conducted by surgeon (Fig. 1). And medical personnel are required to wear identification cards as per the Korean Medical Service Act amendment (article 4), except when they are in the operating room. That is to say, if the patient is rolled into the operating room, it is not mandatory for the surgeon to wear an identification card; thus seemingly impossible to root out ghost surgery without enforcement of wearing identification card. Thus, strict application of the criminal code should be applied to eradicate ghost surgery, though it appears to be on right track in preventing ghost surgery as the Korean Medical Service Act has been revised.

Supreme Court precedents have not been established so far. Therefore, this study reviewed U.S. court precedents, law books, and related academic papers, which have already discussed the legal liabilities for ghost surgery and examines criminal liabilities held by the operating surgeon who performed ghost surgery. However, ghost surgery as defined in this study was limited to a case where a surgeon who did not obtained consent from a patient performed surgery after giving an anesthetic to the patient. Therefore, this study left any surgery performed by an unlicensed surgeon out of discussion. In addition, the following issues were not reviewed in this study as well: minor violations which generally come with ghost surgery, such as omissions or false entries in medical records, and the duty to explain which is inevitably breached to perform ghost surgery. Accordingly, this study reviewed only criminal liability issues involved in ghost surgery itself.

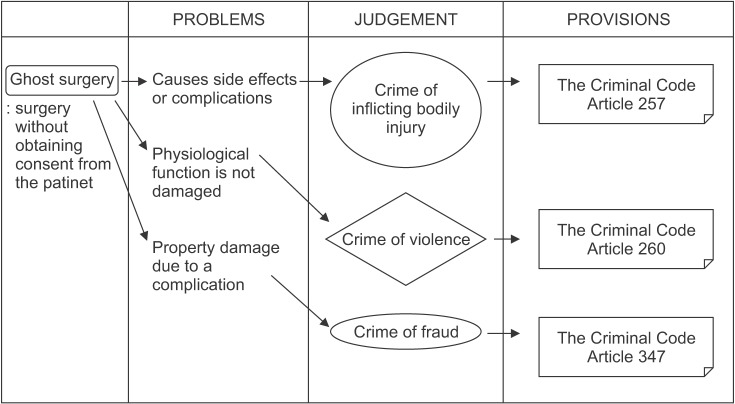

Laws on crimes of inflicting bodily injury [3], violence [4], and fraud [5] are applicable to ghost surgery (Fig. 2).

The crime of inflicting bodily injury under the Korean Criminal Act requires “the intent to inflict bodily injury,” “an act of harming bodily integrity,” and the consequential “outcome of the infliction.” Court precedents have taken up the position that, despite the fact that the medical doctor's act of medical treatment meets the requirements for the crime of inflicting bodily injury, the illegality of such an act is ruled out by patient consent. Academic theories have also held similar views that medical treatment activity is not illegal because it is conducted as part of occupational duties, or that a successful treatment activity that improves and recovers the patient's health cannot be considered to have inflicted any bodily injury; and even an unsuccessful treatment activity should not be deemed to be conducted with intention, or by negligence, and thereby constitute a crime of inflicting bodily injury if such activity was conducted in compliance with the principles of medical practices. Therefore, in Korea, the medical doctor can be punished for causing bodily injury or death by occupational negligence only if the doctor can be recognized as negligent in conducting the treatment activity in compliance with the principles of medical practices. In this regard, court precedents have ruled that, if the medical doctor performs surgery without obtaining consent from the patient, the crime of inflicting bodily injury can be established as there is no ground for ruling out illegality, namely, or the patient's consent. However, as the infliction of bodily injury refers to an act of causing a negative alteration of bodily health and physiological dysfunction to the victim, the question is whether or not ghost surgery that produces a successful outcome also constitutes the crime of injury. In a case where an asymmetry occurred after subbrow excision surgery, the court ruled that the act of making an incision did not constitute the crime of inflicting bodily injury because the medical doctor obtained the victim's consent, and it is difficult to determine that such asymmetry caused any physiological dysfunction to the victim's body [6]. In other words, the court viewed that, even though the medical doctor's act altered the appearance of a patient, such an act cannot be deemed to inflict bodily injury unless the alteration had caused a physiological dysfunction to the patient's body. This court ruling leads us to the conclusion that the surgeon who did ghost surgery without any medical negligence will be exempt from criminal liability for inflicting bodily injury because the surgeon's act did not result in any bodily injury. That is to say, a substitute surgeon will be held liable for inflicting bodily injury if his/her ghost surgery causes side effects or complications and, as a result, harms the stability of the patient's body. However, if the substitute surgeon achieves successful surgical results, the surgeon will be merely charged with the attempted infliction of bodily injury or violence. In addition, if the patient dies after ghost surgery, the surgeon's criminal liability for causing death constitutes bodily injury.

Where it is deemed that the patient's physiological function is not damaged, ghost surgery may be deemed to be the use of physical force to cause injury and, therefore, constitute a crime of violence.

In cases where a gynecologist misdiagnosed the victim's disease as uterine myoma, only explained to the victim the necessity for hysterectomy based on the misdiagnosis and performed the operation without giving any explanation on ectopic pregnancy, the disease the victim actually had, the court ruled that the gynecologist was liable for the injury caused by occupational negligence, deeming that the victim's consent to the surgery was made based on an inaccurate or insufficient explanation and, therefore, could not be considered effective consent that rules out the illegality of surgery [7]. However, while death or injury by negligence can be established only when such negligence occurs without any intention, it is difficult to assume in any case that ghost surgery is conducted by mistake. In other words, unlike the foregoing court case, as ghost surgery always entails the intention, it would be rather reasonable to view that it constitutes the crime of inflicting bodily injury or the crime of violence.

In general, the crime of fraud is established when (1) a perpetrator defrauds another party with intent to instill a false belief in the party being deceived, (2) the deceived party commits acts of disposal in reliance upon such false belief, (3) the deceiving party acquires property or obtains property gains, and (4) a causal relationship is acknowledged among these incidents. A fraudulent act refers to any act which results in other parties' misunderstanding, and in order for ghost surgery to be acknowledged as fraud, a patient must be led to believe that the consulting doctor would perform the procedure. In other words, the patient must have expressly conditioned his/her surgery on the consulting doctor or the consulting doctor must have promised the patient to perform the procedure in person, or the consulting doctor must have convinced the patient to undergo surgery by actively advertising his/her surgical achievements or experiences. In such a case, the substitution of a surgeon without patient consent is considered fraud. Although it is disputable whether the occurrence of property damage is prerequisite to establishing the crime of fraud, those who argue that property damage is not requisite to establishing the crime of fraud are of the view that the crime of fraud is acknowledged irrespective of whether cosmetic surgery patients actually suffered damage. As court precedents are also of the same view [8], ghost surgery may be considered fraud irrespective of the outcomes of cosmetic surgery. However, if property damage is deemed a required element of fraud, the offence of fraud may not be established when surgery received by the patient was what the patient paid for and thus deemed to have caused no property damage to the patient. In such a case, the crime of fraud is established only when the patient sustained property damage due to a complication from the surgery.

Surgery is unusual among medical treatments in that it is performed on voluntarily unconscious patients. Ghost surgery refers to surgery performed by a surgeon whose identity is unknown to the patient. In other words, it is surgery illegally performed by an unauthorized substitute surgeon (i.e., a shadow surgeon) instead of the surgeon with whom the patient has a physician/patient relationship [9]. As the right to harm the patient's body lies only with a surgeon whom the patient allowed to perform the operation, ghost surgery raises significant concerns in terms whereof a third party surgeon performs surgery instead of the surgeon to whom the patient delegated the ‘right to cause bodily harm.’ Even when surgery is carried out by a team of surgeons, as is often the case, the entire surgical procedure must be carried out under the supervision of the attending doctor that the patient consented to. Surgical ghosts are ethically questionable and legally dangerous.

In recent days, the practice of ghost surgery has become rampant within the cosmetic surgery industry in Korea. Patients are misled into believing that the ‘best cosmetic surgeon’ would perform surgery but once patients are anesthetized and become unconscious, a substitute surgeon carries out the procedure. The substitute surgeon relies only on the patient's medical chart in performing surgery without meeting the patient in person and, thus, is not familiar with the facial expressions, or muscle movements, etc., of the patient. Thus, such surgery performed by substitute surgeons is not guaranteed to result in successful outcomes and often results in medical malpractice lawsuits [10]. Foreign plastic surgery tourists to Korea are also suffering from the practice of ghost surgery [11]. However, as ghost surgery is generally carried out when patients are made unconscious under general or sedative anesthesia and the substitute surgeons' names do not appear on the surgical records, it is difficult to confirm whether ghost surgery was performed based only on the statements of the parties concerned. Moreover, since there is no current medical law or court precedent in Korea addressing the issue of ghost surgery, opinions are divided over the extent of rights granted to patients and on what charge must ghost surgeons be held accountable for. Thus, considerations must first be made as to what laws are applicable to ghost surgery and the requirements for the application of such laws.

The practice of ghost surgery is not new in Korea. In fact, it is being commonly adopted in the fields of surgery. Ghost surgery is being performed not only in private hospitals but also in university-affiliated hospitals. However, such hospitals differ from privately owned hospitals in that they also function as teaching hospitals. In university-affiliated hospitals where surgery is generally performed through team efforts, surgical operations are sometimes carried out jointly with other medical departments and at other times when staff and attending doctors are called in, performed in whole or in part by attending doctors. Such surgical scenarios carried out in university-affiliated hospitals may also be viewed as ghost surgery given that the physician examining the patient and the surgeon operating on the patient are not the same. However, since ghost surgery in university-affiliated hospitals is performed for educational purposes, it is significantly different from that performed in the private sector as a means to raise profits. Of course, ghost surgery in university-affiliated hospitals cannot be tolerated under the pretext of education. The court also judged a case in which a university-affiliated hospital made unfair profits by charging extra money to patients for designating their operating surgeons while, in reality, having residents substitute for such designated surgeons to the effect that “even in the case of teaching hospitals such as university-affiliated hospitals, the treatment originally signed up for by patients shall be deemed to have been given only when the designated surgeon was at least present in the operating room to instruct the operating surgeon to prevent any mistake and was fully prepared to correct any mistake which may arise during the procedure” [12]. The court further ruled that “in case the surgeon designated by the patient cannot participate in surgery in person, he/she has the duty of care to notify the patient's guardian before and/or after surgery of such fact so that the patient or his/her guardian may not pay the doctor selection fees,” adding that “in cases where the designated surgeons failed to notify such facts and the patients or their guardians paid the doctor selection fees, a causal relationship between the defendants' failure to notice and the payment of doctor selection fees by the patients and their guardians is established, thereby establishing the crime of fraud.” However, the foregoing court precedent did not hold the hospital accountable for ghost surgery. Under the relevant U.S. court precedent, in cases where a surgical procedure that was believed to be performed by a surgical specialist is carried out by an attending doctor, the surgical specialist was held liable for the crime of inflicting bodily injury and the attending doctor was held liable for compensation for damages resulting from breach of contract, irrespective of whether there was medical malpractice [13]. However, according to the Korean court precedents under which no injury was deemed to have been caused if the outcomes of surgical procedures were desirable, whether medical malpractice occurred becomes critical in establishing the crime of bodily injury. In other words, if a patient suffers from medical malpractice, the responsible surgeon will face a charge of inflicting bodily injury. Otherwise, the responsible surgeon will be charged with attempted bodily injury or assault.

From the point of view of teaching hospitals, however, it is rather natural that several medical staff members jointly participate in an operation either for educational or work-sharing purposes. In order to acquire operation skills, an attending doctor needs not only to take theoretical lessons from professors but also to apply such lessons in practice. Residents must have the opportunity to learn how to perform surgery [14]. Accordingly, unconditional prohibition of the practice is both undesirable and infeasible. The medical profession acknowledges its responsibility to prepare medical students, residents, and fellows to become skillful, experienced, confident, and qualified to perform surgery independently to meet patient needs in the future [1516], and there is no dispute that this practice is ethical and lawful [17]. However, joint-participation can be only justified when a patient or his/her guardian has given prior consent. Patients require information to understand that surgical residents are graduate physicians who are licensed to practice independently but have chosen to specialize their practice and become surgeons. This requires extensive training. In the final year of a surgical residency, a chief resident is considered to be the surgeon's associate, not his assistant [18]. Explanations before surgery may be omitted in case of an emergency, but other than that, a professor giving explanations on an operation and collecting consent thereto must notify that the operation will be performed in a team with residents. The attending surgeon should be present to offer guidance and control risk during any surgery involving a resident, and under these circumstances, most patients are comfortable moving forward [19]. On the other hand, ghost surgery occurring at some private cosmetic surgery hospitals stem from the commercialization of cosmetic surgery. In the past when advertising was not influential in the medical industry, skillful surgeons made their names by word-of-mouth reviews. Nowadays, however, as the power of marketing has grown, a surgeon's reputation does not necessarily correspond to his/her proficiency. Once a doctor gains reputation by frequently appearing on TV shows and other media or by placing constant advertisements, patients will scramble to have an operation from him/her. As the number of reservations for counseling increases, the doctor will become unable to afford the time to operate and have no choice but to delegate operations to another surgeon. However, he/she would not tell patients who expect that the famous doctor would perform the operation that a substitute surgeon will do instead. Of course, cosmetic surgery may be performed by a different surgeon and not the one who consulted with a patient because cosmetic surgery skills are also taught through apprenticeship where an apprentice follows what a professional does, but such cases are extremely rare. Clearly, an implicit social consensus has formed that ghost surgery is not only an ethical issue in the medical industry but also constitutes a crime. Although no court precedent has been established in Korea, the U.S. Supreme Court has rendered a number of decisions in this regard. In Perna v. Pirozzi, 92 N.J. 446, 457 A.2d 431 (1983), the Supreme Court held that such a battery results when a medical procedure is performed by a ‘substitute’ doctor regardless of good intentions. The Court ruled that, where a colleague doctor commenced an operation in place of a previously agreed doctor who was late for the operation and performed only incidental procedures afterwards, the colleague who performed the operation without obtaining patient consent should be punished for inflicting bodily injury regardless of whether there was medical malpractice. No “malice” or intent to injure, however, is required to establish battery in general, or specifically, “ghost surgery”.

The Korean court's position is that although the doctor's medical treatment satisfies the requirements for the crime of inflicting bodily injury, the illegality of such act is ruled out by patient consent. Accordingly, if a surgeon performs an operation without patient consent, such surgeon is guilty of inflicting bodily injury due to the absence of grounds for removing the illegality. Since ghost surgery always occurs with intention, there is no room for asserting negligence; thus, it is more rational and reasonable that ghost surgery constitutes the crime of inflicting bodily injury without occupational negligence, despite any medical malpractice during the operation. Some argue that a patient's death after ghost surgery should be deemed to constitute murder. However, it would be more reasonable to deem the death resulting from bodily injury because it is hard to determine whether the substitute surgeon had the intention of murder. Unlike the U.S. court precedent, the Korean court has taken the position that injury requires damage to physiological function of a body. In this regard, the crime of inflicting injury may not be established unless a complication or adverse reaction occurs after surgery. Without complication or adverse reaction, an attempted injury or crime of violence may be acknowledged. Indeed, it seems somewhat unfair to determine the substitute surgeon's liability for inflicting bodily injury depending on the existence of malpractice by the substitute surgeon. However, given that what legal provision on the crime of injury aims to protect is physical health, it would be reasonable to charge the substitute surgeon with attempted injury or violence in case of successful surgery where any damage to body functions is hardly found.

In finding fraud, the existence of a deceptive act and the occurrence of property damage, among others, would be at issue. The issue regarding whether the substitute surgeon's liability for fraud can be acknowledged may arise in both cases: (1) where the patient was given an explanation that the consulting doctor would perform surgery, but actually had an operation by a substitute surgeon and (2) where the patient was given no clear explanation on who would operate. In cases of large cosmetic surgery hospitals where a number of surgeons are employed, some patients visit for the reputation of the hospital itself, not individual doctors, and in such cases, it is difficult to consider that a consulting doctor has deceptive intent even if he/she does not perform surgery because patients do not expect to have an operation from a specific doctor. On the contrary, in certain circumstances where the patient may have faith that the consulting doctor will perform the operation, the consulting doctor has an obligation to give information on the operating doctor. In other words, once the patient is made to believe that a certain doctor will perform the operation, and if such doctor fails to do so, he/she will be deemed to have had deceptive intent. With regard to property damage, as court precedents ruled that property damage is not factored into when determining the crime of fraud, it is likely that fraud can be recognized in ghost surgery regardless of the outcome of surgery. Although there is a theory that fraud requires the occurrence of property damage [20], the Korean Criminal Act does not expressively require the occurrence of property damage. Also, even if the quality of an operation is worth the price paid, the goal of transaction intended by the victim was not achieved, i.e., the operation was not performed by the consulting doctor. In this regard, it should be deemed that there was critical failure in the essential part of juristic act and, thus, fraud can be established because there was an act of taking the other party's profit by deceiving him/her.

Before an operation, a patient gives consent that his/her body may be harmed, and only the person who is “delegated with this right to cause bodily harm” can perform the operation. It means that “patient's consent” has an absolute priority over “doctor's license” for a lawful operation to be acknowledged. The patient is entitled to choose his own physician and he should be permitted to acquiescing or refuse to accept the substitution. The surgeon's obligation to the patient requires him to perform the surgical operation: (1) within the scope of authority granted by the consent to the operation, (2) in accordance with the terms of the contractual relationship, (3) with complete disclosure of all facts relevant to the need and the performance of the operation, and (4) to utilize his best skill in performing the operation [21]. A surgeon should bear in mind that failure to do this will be deemed a crime as shown above. The strongest weapon to root out ghost surgery is not laws or regulations, but the conscience of individual doctors. Unlike other clinical areas, the cosmetic surgery industry is distinctive in that commercial business and medical field are mixed. However, what needs to be remembered is that cosmetic surgery is also within the boundary of medical care, aside from commercial business. Although the time has passed when the ethics and conscience of medical personnel were most important and “money” has taken precedence, doctors should put top priority on the safety of patients as nothing is more valuable than a person's life.

References

1. Shim YG. Can ‘ghost surgery’ be punished? SBS News [Internet]. 2015. 3. 19. cited 2016 Jan 25. Available from: http://news.sbs.co.kr/news/endPage.do?news_id=N1002887732.

2. Dunn D. Ghost Surgery: A Frank Look at the Issue and How to Address It. AORN J. 2015; 102:603–613. PMID: 26616321.

3. Inflicting bodily injury on other or on lineal ascendant criminal act, article No. 257.

4. Crime of violence act, article No. 260.

5. Fraud act, article No. 347.

6. Seoul Southern District Court Decision No. 2006No1069. 2007. 2. 07.

7. Supreme Court Judgment No. 92Do2345. 1993. 7. 27.

8. Supreme Court Judgment No. 2010Do 12928. 2010. 12. 09.

9. Lundmark T. Surgery by an unauthorized surgeon as a battery. J Law Health. 1995-1996; 10:287–296.

10. Ghost surgery is a murder... There must be measures to prevent it. Newsis [Internet]. 2015. 3. 17. cited 2016 Jan 25. Available from: http://www.newsis.com/ar_detail/view.html?ar_id=NISX20150317_0013541683&cID=10201&pID=10200.

11. Ahn AR. Promoting ghost surgery--Thousands of brokers--Foreigners under illegal plastic surgery. Hankookilbo [Internet]. 2015. 4. 25. cited Jan 25. Available from: http://www.hankookilbo.com/v/5e418c0128ec4ecf95c41769c30d1ba6.

12. Seoul High Court (10th Criminal Division) Judgment No. 99No525. 2000. 1. 12.

13. Superior Court of Pennsylvania (US). Taylor v. Albert Einstein Medical Center, 723 A.2d 1027, 1034 (1998), Dingle v. Belin, 732 A.2d 301 (1999, Court of Special Appeals of Maryland).

14. Holmes MK. Ghost surgery. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1980; 56:412–419. PMID: 6929212.

15. Connell JF Jr. Ghost surgery. Interview by Jim Hoffman. Fam Health. 1978; 10:24–27. PMID: 10316714.

16. Jones JW, McCullough LB. Consent for residents to perform surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2002; 36:655–656. PMID: 12218999.

17. Holmes MK. Ghost surgery. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1980; 56:412–419. PMID: 6929212.

19. Jones JW, McCullough LB. Consent for residents to perform surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2002; 36:655–656. PMID: 12218999.

20. Kim JH. Whether property damage is requisite for establishment of fraud. New Trend Crim Law. 2015; 49:309–342.

21. Judicial Council of the American Medical Association, Opinion #8. 1982. 12.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download