INTRODUCTION

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has been one of the major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Although significant progress improving prognosis after AMI has been made in past decades mainly attributed to increased application of reperfusion therapies, including percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as well as guideline-adherent pharmacological therapies,

1) all-cause mortality at 2 years amounted to 6.2% among patients with AMI,

2) and rates of re-hospitalization due to acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and revascularization were 6.8% and 4.1%, respectively.

3)

Several prognostic models have been developed for patients with ST-segment elevation AMI and for ACS without ST-segment elevation.

4)5) However, less attention has been paid to predicting outcomes and long-term risk stratification in patients treated with contemporary guideline-adherent optimal therapies after AMI. The risk model in this population could differ from that in the entire spectrum of an unselected population of patients with AMI.

6) Therefore, the goal of our study was to develop a new risk scoring system for 1-year all-cause death or myocardial infarction (MI) in AMI survivors treated with guideline-adherent therapies, including PCI and secondary preventive optimal medications. Furthermore, the prognostic accuracy of this new Korea Working Group in Myocardial Infarction (KorMI) system was compared with those of previous models, such as the Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction (APEX AMI),

7) the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC),

8) and the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events scores (GRACE)

5) in terms of discrimination,

9) goodness-of-fit,

10) the continuous-net reclassification improvement (NRI), the integrated discrimination index (IDI), and the median improvement in risk score

11) in prospective, multi-center, national AMI registries.

METHODS

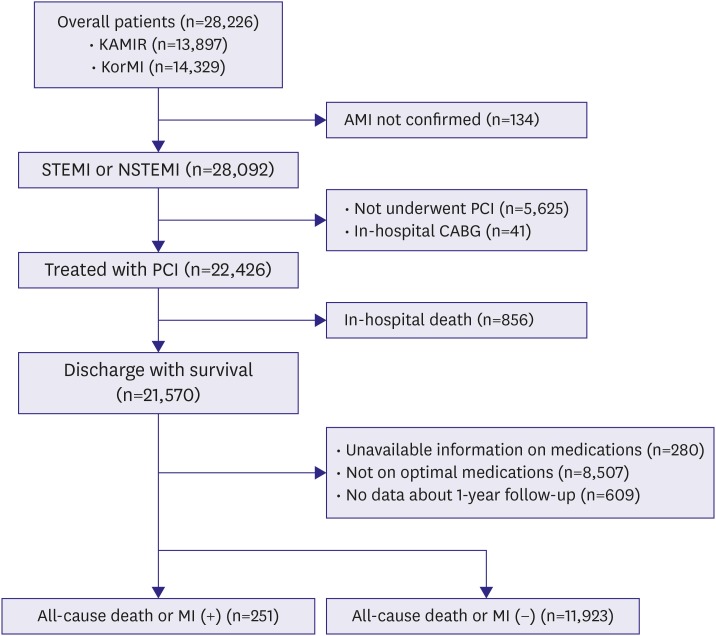

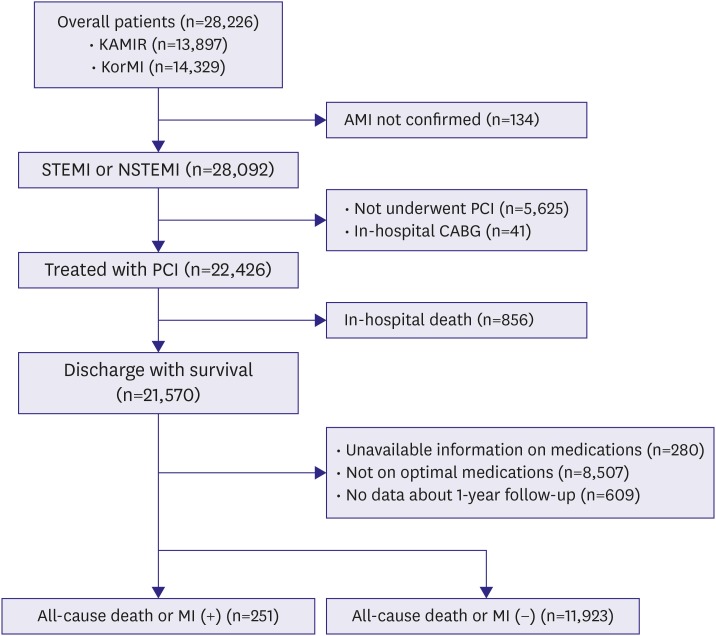

The present study was derived from the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR) and the KorMI registry, which are nationwide, prospective, multicenter, and observational registries designed to establish a standardized practice guideline for AMI patients in Korea. It began in November 2005, and 53 centers that were capable of performing a large number of primary PCIs participated. The ethics committee at each participating institution reviewed and approved this study protocol prior to data collection. A trained study coordinator collected clinical, laboratory, and outcome data using a standardized web-based case report form and protocol. We pooled clinical data of patients enrolled in the KAMIR and KorMI registry. A total of 28,226 consecutive patients were enrolled prospectively in these registries. Among them, inclusion criteria for this analysis were: 1) patients ≥18-years-of-age; 2) patients diagnosed with ST-segment elevation AMI or non-ST-segment elevation AMI; 3) patients treated with PCI; 4) patients subsequently discharged from the hospital alive; and 5) patients who were on all 5 guideline-adherent optimal medical therapies at discharge. Exclusion criteria were: 1) in-hospital coronary artery bypass grafting surgery; 2) invalid data; and 3) lost to clinical follow-up (

Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart of patient enrollment.

AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; KAMIR = Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry; KorMI = Korea Working Group in Myocardial Infarction; MI = myocardial infarction; NSTEMI = non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Each clinical outcome was classified by the report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on clinical data standards.

12) The primary outcome was all-cause death or MI during the 1-year follow-up period. Deaths were defined as all-cause mortality during follow-up. MI was defined as recurrent symptoms with new electrocardiographic changes compatible with AMI or cardiac-specific marker levels at least greater than the 99th percentile upper reference limit as the reference standard. All events were identified by the patient's physician and confirmed by the principal investigator of each hospital. When necessary, we documented additional information by contacting the principal investigators at each hospital or reviewing hospital records, or both. The information about death was confirmed through records from the National Population Registry of the Korea. The guideline-adherent optimal medical therapies were defined as use of all 5 medication types, including aspirin, thienopyridine, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and statins. Estimated creatinine clearance was calculated according to the Cockcroft-Gault formula.

13) Renal insufficiency was considered an estimated creatinine clearance <60 mL/min. Left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction was defined as an LV ejection fraction <50% on initial 2-dimensional echocardiography. The APEX AMI, CADILLAC, and GRACE scores were calculated based on patient clinical characteristics using published algorithms (

Supplementary Materials 1,

2,

3).

5)7)8)

Categorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and compared using the χ

2 test. Continuous variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or mean±standard deviation and were compared using the t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, when applicable. A univariate analysis was used to examine the individual relationships between baseline parameters and primary outcome. All variables in

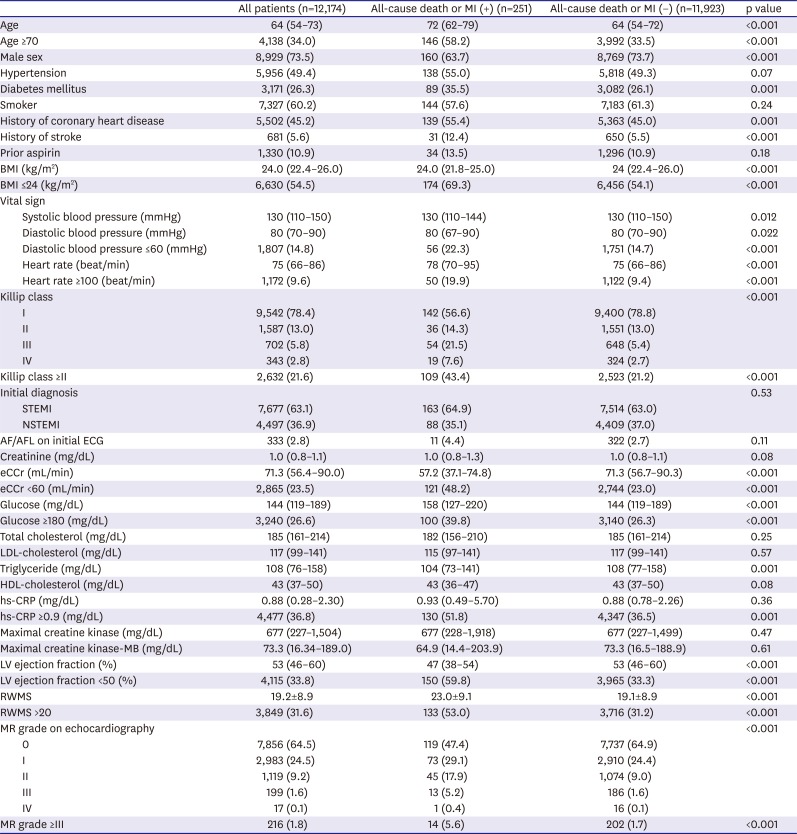

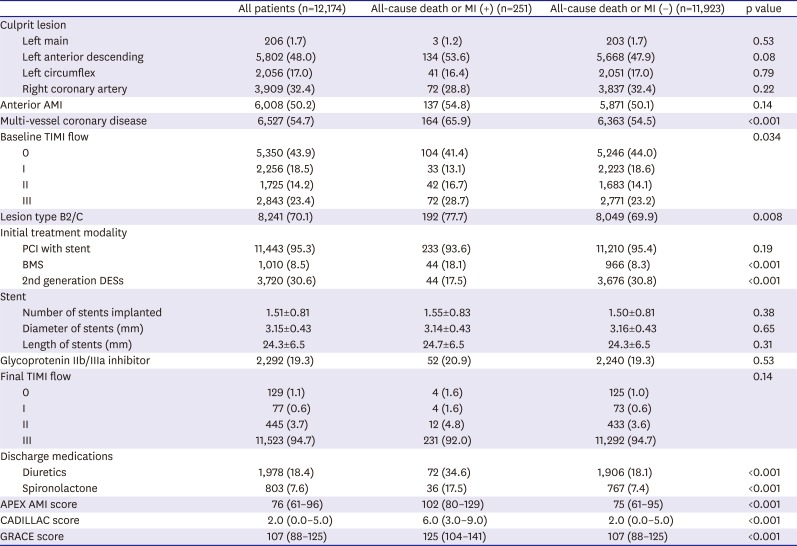

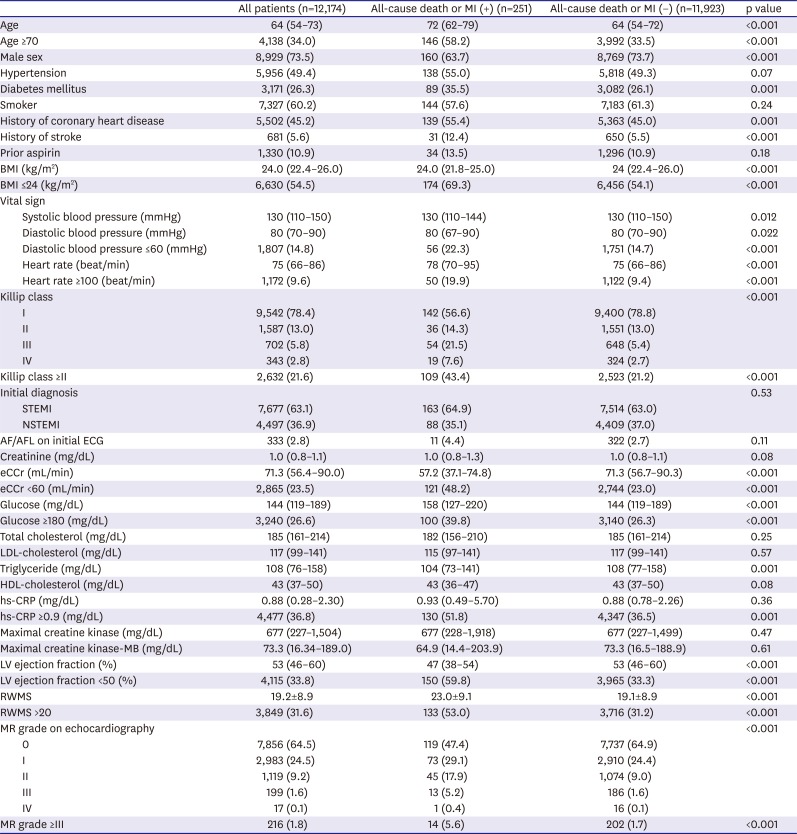

Tables 1 and

2 were available for the univariate analysis. All continuous variables were dichotomized and treated as binary variables in order to choose the cutoffs by all-cause death or MI during the 1-year follow-up period as the outcome measure to discriminate the value of all continuous variables proposed to be used as decisional levels in clinical practice when it is necessary, based on the results of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves using MedCalc ver. 11.3.6.0 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Variables achieving a significance level of p<0.001 in the univariate analysis were eligible to enter the multivariate analysis. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the risk posed by patient factors on 1-year all-cause death or MI using a stepwise multivariate Cox regression hazard analysis. The independent predictors of 1-year all-cause death or MI were assigned a risk score based on their adjusted HRs, and risk scores were calculated for each patient from the sum of the individual scores. The discriminative power of the KorMI system was assessed by the mean of the area under the time-dependent ROC curve (the time-dependent C statistic), which was estimated using inverse probability of censoring weights without competing risks.

9)14) A 95% CI for the time-dependent C statistic was derived from the jackknife method of correlated on-sample U-statistics. The goodness-of-fit of the KorMI system was evaluated by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

10) Then, 3 risk strata (low, intermediate, and high risk) were categorized for the KorMI system. Among these 3 risk groups (tertiles), all-cause death or MI was estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and cumulative incidence curves were compared across risk strata using the Log-rank test. Furthermore, the KorMI risk scoring system was compared to the APEX AMI, CADILLAC, and GRACE risk scores using the differences between 2 areas under the time-dependent ROC curves in the 95% CI. The proposed methodology for comparison between the time-dependent ROC curves was implemented in the timeROC package written in R (R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria, 2013).

14) The prognostic accuracy of each score was further assessed by the continuous-NRI, the IDI, and the median improvement in risk score.

11)15) We utilized a perturbation-resampling method, which is similar to a wild bootstrapping procedure, to generate independent realizations of a process that had the same distribution as the preceding limiting Gaussian process for comparing between the IDI, the continuous-NRI, and the median improvement in risk score. Data were analyzed using SAS ver. 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All reported p values are 2-sided, and p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Table 1

Baseline clinical characteristics

|

All patients (n=12,174) |

All-cause death or MI (+) (n=251) |

All-cause death or MI (−) (n=11,923) |

p value |

|

Age |

64 (54–73) |

72 (62–79) |

64 (54–72) |

<0.001 |

|

Age ≥70 |

4,138 (34.0) |

146 (58.2) |

3,992 (33.5) |

<0.001 |

|

Male sex |

8,929 (73.5) |

160 (63.7) |

8,769 (73.7) |

<0.001 |

|

Hypertension |

5,956 (49.4) |

138 (55.0) |

5,818 (49.3) |

0.07 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

3,171 (26.3) |

89 (35.5) |

3,082 (26.1) |

0.001 |

|

Smoker |

7,327 (60.2) |

144 (57.6) |

7,183 (61.3) |

0.24 |

|

History of coronary heart disease |

5,502 (45.2) |

139 (55.4) |

5,363 (45.0) |

0.001 |

|

History of stroke |

681 (5.6) |

31 (12.4) |

650 (5.5) |

<0.001 |

|

Prior aspirin |

1,330 (10.9) |

34 (13.5) |

1,296 (10.9) |

0.18 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

24.0 (22.4–26.0) |

24.0 (21.8–25.0) |

24 (22.4–26.0) |

<0.001 |

|

BMI ≤24 (kg/m2) |

6,630 (54.5) |

174 (69.3) |

6,456 (54.1) |

<0.001 |

|

Vital sign |

|

|

|

|

|

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

130 (110–150) |

130 (110–144) |

130 (110–150) |

0.012 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

80 (70–90) |

80 (67–90) |

80 (70–90) |

0.022 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure ≤60 (mmHg) |

1,807 (14.8) |

56 (22.3) |

1,751 (14.7) |

<0.001 |

|

Heart rate (beat/min) |

75 (66–86) |

78 (70–95) |

75 (66–86) |

<0.001 |

|

Heart rate ≥100 (beat/min) |

1,172 (9.6) |

50 (19.9) |

1,122 (9.4) |

<0.001 |

|

Killip class |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

I |

9,542 (78.4) |

142 (56.6) |

9,400 (78.8) |

|

II |

1,587 (13.0) |

36 (14.3) |

1,551 (13.0) |

|

III |

702 (5.8) |

54 (21.5) |

648 (5.4) |

|

IV |

343 (2.8) |

19 (7.6) |

324 (2.7) |

|

Killip class ≥II |

2,632 (21.6) |

109 (43.4) |

2,523 (21.2) |

<0.001 |

|

Initial diagnosis |

|

|

|

0.53 |

|

STEMI |

7,677 (63.1) |

163 (64.9) |

7,514 (63.0) |

|

NSTEMI |

4,497 (36.9) |

88 (35.1) |

4,409 (37.0) |

|

AF/AFL on initial ECG |

333 (2.8) |

11 (4.4) |

322 (2.7) |

0.11 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

1.0 (0.8–1.1) |

1.0 (0.8–1.3) |

1.0 (0.8–1.1) |

0.08 |

|

eCCr (mL/min) |

71.3 (56.4–90.0) |

57.2 (37.1–74.8) |

71.3 (56.7–90.3) |

<0.001 |

|

eCCr <60 (mL/min) |

2,865 (23.5) |

121 (48.2) |

2,744 (23.0) |

<0.001 |

|

Glucose (mg/dL) |

144 (119–189) |

158 (127–220) |

144 (119–189) |

<0.001 |

|

Glucose ≥180 (mg/dL) |

3,240 (26.6) |

100 (39.8) |

3,140 (26.3) |

<0.001 |

|

Total cholesterol (mg/dL) |

185 (161–214) |

182 (156–210) |

185 (161–214) |

0.25 |

|

LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) |

117 (99–141) |

115 (97–141) |

117 (99–141) |

0.57 |

|

Triglyceride (mg/dL) |

108 (76–158) |

104 (73–141) |

108 (77–158) |

0.001 |

|

HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) |

43 (37–50) |

43 (36–47) |

43 (37–50) |

0.08 |

|

hs-CRP (mg/dL) |

0.88 (0.28–2.30) |

0.93 (0.49–5.70) |

0.88 (0.78–2.26) |

0.36 |

|

hs-CRP ≥0.9 (mg/dL) |

4,477 (36.8) |

130 (51.8) |

4,347 (36.5) |

0.001 |

|

Maximal creatine kinase (mg/dL) |

677 (227–1,504) |

677 (228–1,918) |

677 (227–1,499) |

0.47 |

|

Maximal creatine kinase-MB (mg/dL) |

73.3 (16.34–189.0) |

64.9 (14.4–203.9) |

73.3 (16.5–188.9) |

0.61 |

|

LV ejection fraction (%) |

53 (46–60) |

47 (38–54) |

53 (46–60) |

<0.001 |

|

LV ejection fraction <50 (%) |

4,115 (33.8) |

150 (59.8) |

3,965 (33.3) |

<0.001 |

|

RWMS |

19.2±8.9 |

23.0±9.1 |

19.1±8.9 |

<0.001 |

|

RWMS >20 |

3,849 (31.6) |

133 (53.0) |

3,716 (31.2) |

<0.001 |

|

MR grade on echocardiography |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

0 |

7,856 (64.5) |

119 (47.4) |

7,737 (64.9) |

|

I |

2,983 (24.5) |

73 (29.1) |

2,910 (24.4) |

|

II |

1,119 (9.2) |

45 (17.9) |

1,074 (9.0) |

|

III |

199 (1.6) |

13 (5.2) |

186 (1.6) |

|

IV |

17 (0.1) |

1 (0.4) |

16 (0.1) |

|

MR grade ≥III |

216 (1.8) |

14 (5.6) |

202 (1.7) |

<0.001 |

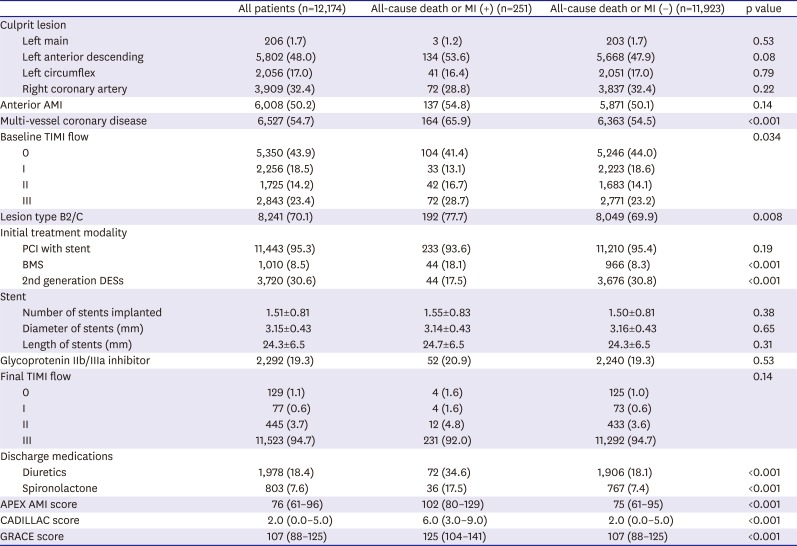

Table 2

Baseline angiographic, procedural, and in-hospital characteristics

|

All patients (n=12,174) |

All-cause death or MI (+) (n=251) |

All-cause death or MI (−) (n=11,923) |

p value |

|

Culprit lesion |

|

|

|

|

|

Left main |

206 (1.7) |

3 (1.2) |

203 (1.7) |

0.53 |

|

Left anterior descending |

5,802 (48.0) |

134 (53.6) |

5,668 (47.9) |

0.08 |

|

Left circumflex |

2,056 (17.0) |

41 (16.4) |

2,051 (17.0) |

0.79 |

|

Right coronary artery |

3,909 (32.4) |

72 (28.8) |

3,837 (32.4) |

0.22 |

|

Anterior AMI |

6,008 (50.2) |

137 (54.8) |

5,871 (50.1) |

0.14 |

|

Multi-vessel coronary disease |

6,527 (54.7) |

164 (65.9) |

6,363 (54.5) |

<0.001 |

|

Baseline TIMI flow |

|

|

|

0.034 |

|

0 |

5,350 (43.9) |

104 (41.4) |

5,246 (44.0) |

|

I |

2,256 (18.5) |

33 (13.1) |

2,223 (18.6) |

|

II |

1,725 (14.2) |

42 (16.7) |

1,683 (14.1) |

|

III |

2,843 (23.4) |

72 (28.7) |

2,771 (23.2) |

|

Lesion type B2/C |

8,241 (70.1) |

192 (77.7) |

8,049 (69.9) |

0.008 |

|

Initial treatment modality |

|

|

|

|

|

PCI with stent |

11,443 (95.3) |

233 (93.6) |

11,210 (95.4) |

0.19 |

|

BMS |

1,010 (8.5) |

44 (18.1) |

966 (8.3) |

<0.001 |

|

2nd generation DESs |

3,720 (30.6) |

44 (17.5) |

3,676 (30.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Stent |

|

|

|

|

|

Number of stents implanted |

1.51±0.81 |

1.55±0.83 |

1.50±0.81 |

0.38 |

|

Diameter of stents (mm) |

3.15±0.43 |

3.14±0.43 |

3.16±0.43 |

0.65 |

|

Length of stents (mm) |

24.3±6.5 |

24.7±6.5 |

24.3±6.5 |

0.31 |

|

Glycoprotenin IIb/IIIa inhibitor |

2,292 (19.3) |

52 (20.9) |

2,240 (19.3) |

0.53 |

|

Final TIMI flow |

|

|

|

0.14 |

|

0 |

129 (1.1) |

4 (1.6) |

125 (1.0) |

|

I |

77 (0.6) |

4 (1.6) |

73 (0.6) |

|

II |

445 (3.7) |

12 (4.8) |

433 (3.6) |

|

III |

11,523 (94.7) |

231 (92.0) |

11,292 (94.7) |

|

Discharge medications |

|

|

|

|

|

Diuretics |

1,978 (18.4) |

72 (34.6) |

1,906 (18.1) |

<0.001 |

|

Spironolactone |

803 (7.6) |

36 (17.5) |

767 (7.4) |

<0.001 |

|

APEX AMI score |

76 (61–96) |

102 (80–129) |

75 (61–95) |

<0.001 |

|

CADILLAC score |

2.0 (0.0–5.0) |

6.0 (3.0–9.0) |

2.0 (0.0–5.0) |

<0.001 |

|

GRACE score |

107 (88–125) |

125 (104–141) |

107 (88–125) |

<0.001 |

RESULTS

Our study population consisted of 12,174 patients with AMI. Median age of the study population was 64 years old (IQR, 54–73 years) and 63.1% presented with ST-segment elevation AMI. A total of 49.4% of the patients had hypertension, 26.3% had diabetes, and 23.5% had renal insufficiency. Median LV ejection fraction was 53% (IQR, 46–60%) and bare-metal stents (BMSs) were implanted in 8.5% of all patients. During a mean follow-up of 287±138 days after hospital presentation, 251 (2.1%) of all-cause deaths or MIs were recorded, including 187 (1.54%) deaths and 67 (0.55%) MIs.

Tables 1 and

2 present the differences in the baseline characteristics between patients with and without all-cause death or MI.

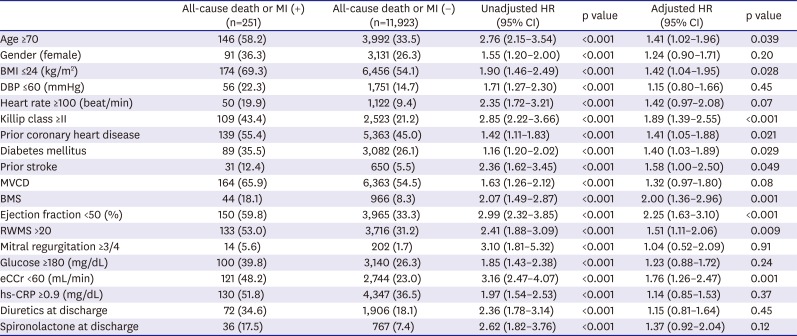

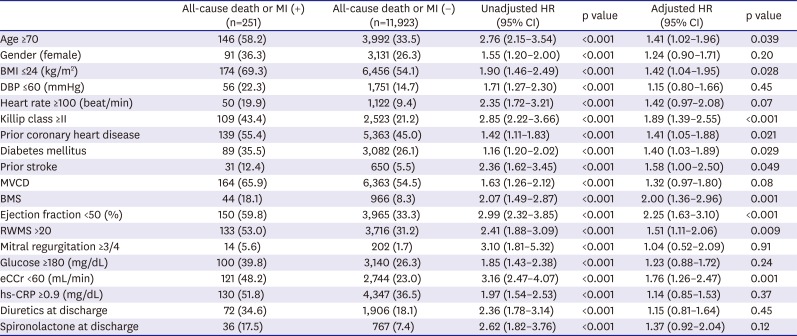

The independent predictors with p<0.001 in the univariate analysis are shown

Table 3. All 19 variables in

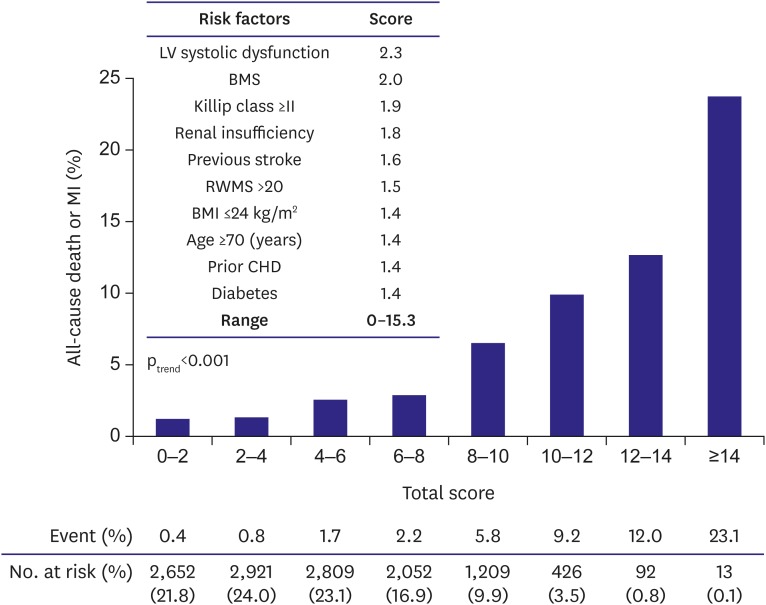

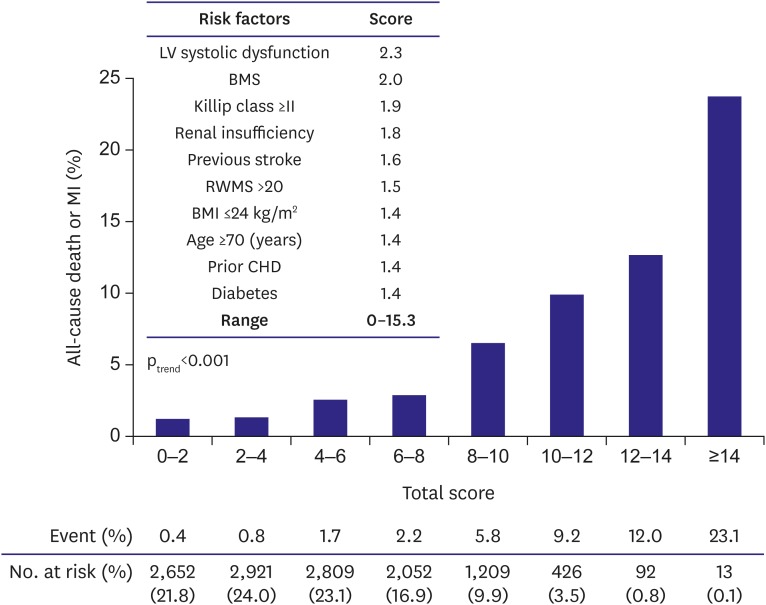

Table 3 were included in the multivariate analysis. The multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed 10 independent factors that increased the risk of all-cause death or MI (in an order of higher HR): LV systolic dysfunction on 2-dimensional echocardiography, BMS as the index stent, Killip class ≥II at presentation, renal insufficiency, previous stroke, regional wall motion score (RWMS) >20 on 2-dimensional echocardiography, body mass index (BMI) ≤24 kg/m

2, age ≥70 years, prior coronary heart disease, and diabetes (

Table 3). Among them, LV systolic dysfunction was the most powerful predictor, with a 2.3-fold increased risk for all-cause death or MI. BMS had nearly the same prognostic significance, with a 2.0-fold increased risk. The independent predictors of 1-year all-cause death or MI were assigned a risk score based on their adjusted HRs in the multivariate analysis, and a total risk score was calculated for each patient with a range of 0 to 15.3 points (

Figure 2). The time-dependent C statistic was 0.759 (95% CI, 0.751–0.767), suggesting reasonably good discriminating power of the model between patients with or without all-cause death or MI. Similarly, the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was not significant, indicating little deviation from a perfect fit (χ

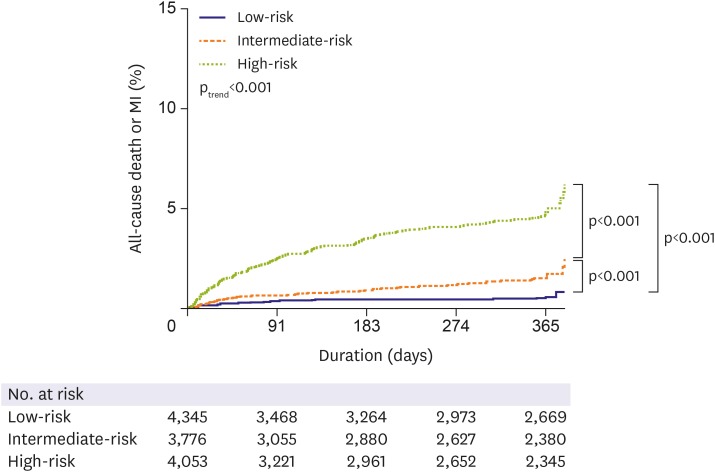

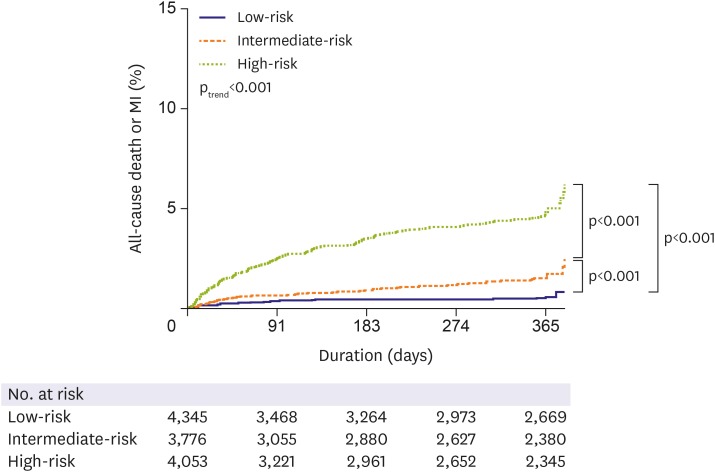

2, 3.50; df, 7; p=0.84). The KorMI risk score was a univariate predictor of primary outcome (unadjusted HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.30–1.40; p<0.001). The KorMI system displayed good predictive values for all-cause death and MI on the Kaplan-Meier survival curves (p

trend<0.001) when we stratified the study population into 3 tertiles (low [0.0–2.9 points], intermediate [3.0–5.6], and high [≥5.7] risk tertiles) according to the KorMI score; an 8.6-fold graded increase in 1-year all-cause death or MI was observed between patients with a low risk score and those with a high risk score (0.5% vs. 4.3%; unadjusted HR, 8.19; 95% CI, 5.30–12.64; p<0.001), and a 3.1-fold graded increase between patients with an intermediate risk score and those with a high risk score (1.4% vs. 4.3%; unadjusted HR, 3.16; 95% CI, 2.33–4.30; p<0.001,

Figure 3).

Table 3

Independent predictors of 1-year all-cause death or MI

|

All-cause death or MI (+) (n=251) |

All-cause death or MI (−) (n=11,923) |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

p value |

Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

p value |

|

Age ≥70 |

146 (58.2) |

3,992 (33.5) |

2.76 (2.15–3.54) |

<0.001 |

1.41 (1.02–1.96) |

0.039 |

|

Gender (female) |

91 (36.3) |

3,131 (26.3) |

1.55 (1.20–2.00) |

<0.001 |

1.24 (0.90–1.71) |

0.20 |

|

BMI ≤24 (kg/m2) |

174 (69.3) |

6,456 (54.1) |

1.90 (1.46–2.49) |

<0.001 |

1.42 (1.04–1.95) |

0.028 |

|

DBP ≤60 (mmHg) |

56 (22.3) |

1,751 (14.7) |

1.71 (1.27–2.30) |

<0.001 |

1.15 (0.80–1.66) |

0.45 |

|

Heart rate ≥100 (beat/min) |

50 (19.9) |

1,122 (9.4) |

2.35 (1.72–3.21) |

<0.001 |

1.42 (0.97–2.08) |

0.07 |

|

Killip class ≥II |

109 (43.4) |

2,523 (21.2) |

2.85 (2.22–3.66) |

<0.001 |

1.89 (1.39–2.55) |

<0.001 |

|

Prior coronary heart disease |

139 (55.4) |

5,363 (45.0) |

1.42 (1.11–1.83) |

<0.001 |

1.41 (1.05–1.88) |

0.021 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

89 (35.5) |

3,082 (26.1) |

1.16 (1.20–2.02) |

<0.001 |

1.40 (1.03–1.89) |

0.029 |

|

Prior stroke |

31 (12.4) |

650 (5.5) |

2.36 (1.62–3.45) |

<0.001 |

1.58 (1.00–2.50) |

0.049 |

|

MVCD |

164 (65.9) |

6,363 (54.5) |

1.63 (1.26–2.12) |

<0.001 |

1.32 (0.97–1.80) |

0.08 |

|

BMS |

44 (18.1) |

966 (8.3) |

2.07 (1.49–2.87) |

<0.001 |

2.00 (1.36–2.96) |

0.001 |

|

Ejection fraction <50 (%) |

150 (59.8) |

3,965 (33.3) |

2.99 (2.32–3.85) |

<0.001 |

2.25 (1.63–3.10) |

<0.001 |

|

RWMS >20 |

133 (53.0) |

3,716 (31.2) |

2.41 (1.88–3.09) |

<0.001 |

1.51 (1.11–2.06) |

0.009 |

|

Mitral regurgitation ≥3/4 |

14 (5.6) |

202 (1.7) |

3.10 (1.81–5.32) |

<0.001 |

1.04 (0.52–2.09) |

0.91 |

|

Glucose ≥180 (mg/dL) |

100 (39.8) |

3,140 (26.3) |

1.85 (1.43–2.38) |

<0.001 |

1.23 (0.88–1.72) |

0.24 |

|

eCCr <60 (mL/min) |

121 (48.2) |

2,744 (23.0) |

3.16 (2.47–4.07) |

<0.001 |

1.76 (1.26–2.47) |

0.001 |

|

hs-CRP ≥0.9 (mg/dL) |

130 (51.8) |

4,347 (36.5) |

1.97 (1.54–2.53) |

<0.001 |

1.14 (0.85–1.53) |

0.37 |

|

Diuretics at discharge |

72 (34.6) |

1,906 (18.1) |

2.36 (1.78–3.14) |

<0.001 |

1.15 (0.81–1.64) |

0.45 |

|

Spironolactone at discharge |

36 (17.5) |

767 (7.4) |

2.62 (1.82–3.76) |

<0.001 |

1.37 (0.92–2.04) |

0.12 |

Figure 2

Risk scoring system and corresponding 1-year all-cause death or MI rates.

BMI = body mass index; BMS = bare-metal stent; CHD = coronary heart disease; LV = left ventricular; MI = myocardial infarction; RWMS = regional wall motion score.

Figure 3

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for 1-year all-cause death or MI in each tertile of the KorMI risk score.

KorMI = Korea Working Group in Myocardial Infarction; MI = myocardial infarction.

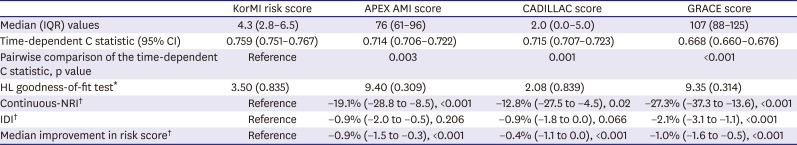

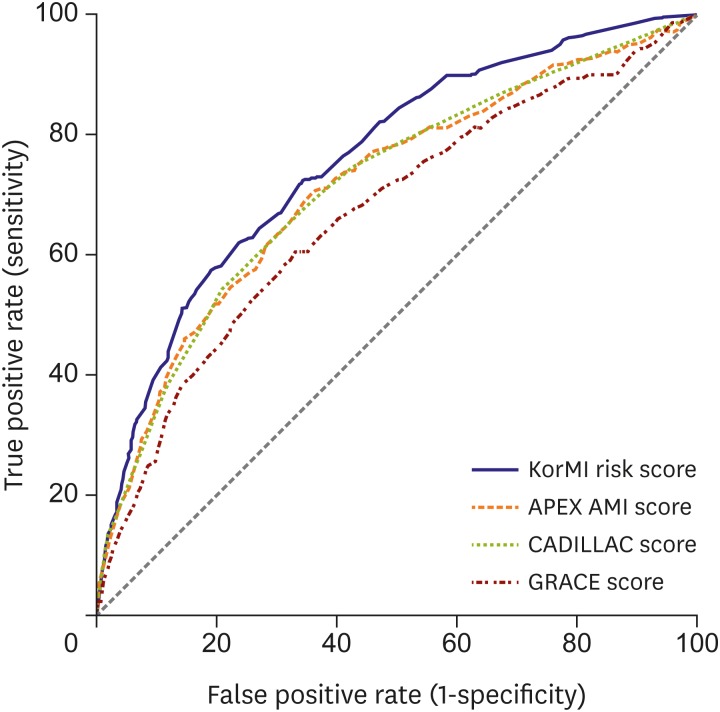

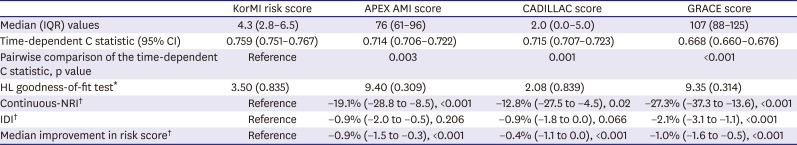

The performances of the KorMI risk scoring system and the other scoring models in the present population are shown in

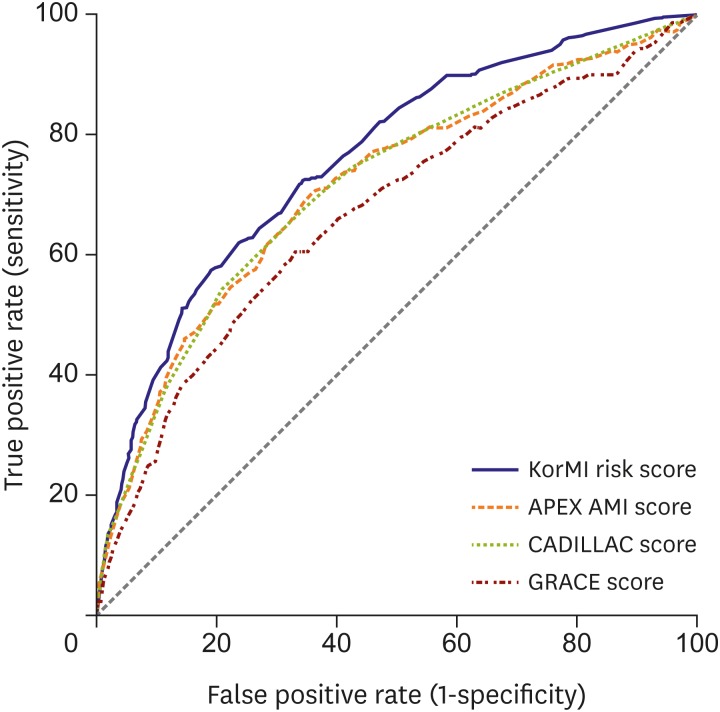

Table 4. Among the 4 scores, the discriminatory ability determined by the time-dependent C statistic was 0.759 (95% CI, 0.751–0.767) for the KorMI risk scoring system, 0.714 (95% CI, 0.706–0.722) for the APEX AMI, 0.715 (95% CI, 0.707–0.723) for the CADILLAC, and 0.668 (95% CI, 0.660–0.676) for the GRACE models (

Figure 4). Moreover, the continuous-NRI varied from −27.3% to −19.1%, the IDI varied from −2.1% to −0.9%, and median improvement in the risk score was from −1.0% to −0.4%.

Table 4

Prognostic accuracy of risk scores in AMI

|

KorMI risk score |

APEX AMI score |

CADILLAC score |

GRACE score |

|

Median (IQR) values |

4.3 (2.8–6.5) |

76 (61–96) |

2.0 (0.0–5.0) |

107 (88–125) |

|

Time-dependent C statistic (95% CI) |

0.759 (0.751–0.767) |

0.714 (0.706–0.722) |

0.715 (0.707–0.723) |

0.668 (0.660–0.676) |

|

Pairwise comparison of the time-dependent C statistic, p value |

Reference |

0.003 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

|

HL goodness-of-fit test*

|

3.50 (0.835) |

9.40 (0.309) |

2.08 (0.839) |

9.35 (0.314) |

|

Continuous-NRI†

|

Reference |

−19.1% (−28.8 to −8.5), <0.001 |

−12.8% (−27.5 to −4.5), 0.02 |

−27.3% (−37.3 to −13.6), <0.001 |

|

IDI†

|

Reference |

−0.9% (−2.0 to −0.5), 0.206 |

−0.9% (−1.8 to 0.0), 0.066 |

−2.1% (−3.1 to −1.1), <0.001 |

|

Median improvement in risk score†

|

Reference |

−0.9% (−1.5 to −0.3), <0.001 |

−0.4% (−1.1 to 0.0), <0.001 |

−1.0% (−1.6 to −0.5), <0.001 |

Figure 4

ROC curves for the KorMI, APEX AMI, CADILLAC, and GRACE scores for 1-year all-cause death or MI in patients with AMI.

AMI = acute myocardial infarction; APEX AMI = Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction; CADILLAC = Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications; GRACE = Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; KorMI = Korea Working Group in Myocardial Infarction; MI = myocardial infarction; ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

DISCUSSION

We used data of patients with AMI in prospective national registries and confirmed the prognostic importance of 10 variables independently predictive of adverse outcomes in patients with AMI treated using guideline-adherent optimal therapies. A 1-year all-cause death or MI increased more than 8-fold across tertiles of the KorMI risk scoring system. When compared with the APEX AMI, CADILLAC, and GRACE models, the KorMI system displayed good accuracy in terms of discrimination and goodness-of-fit, as the continuous-NRI varied from −27.3% to −19.1%, the IDI varied from −2.1% to −0.9%, and the median improvement in risk score was from −1.0% to −0.4%.

Despite the availability of several AMI or ACS prognostic risk models for identifying high-risk patients,

4)5) no appropriate scoring system is available for risk stratification of patients with AMI in the contemporary practice of treatment. Therefore, the KorMI system was created specifically for survivors of an AMI treated with contemporary guideline-adherent optimal therapies.

Our system shares many variables with prior mortality prediction models.

16)17)18)19)20)21)22) However, one difference is that LV systolic dysfunction constituted a greater proportion of the predictive information than that in prior clinical trial models. Patients with LV systolic dysfunction after AMI have increased mortality.

16) Thus, assessing resting LV function is an important part of risk stratification in these patients, and the current guidelines recommend that LV ejection fraction should be measured in all AMI patients with contrast ventriculography or transthoracic echocardiography. In addition, 2-dimensional echocardiography has the added advantage of detecting other factors that can be associated with a worse prognosis, such as diastolic dysfunction, mitral regurgitation, or a high wall motion score index.

17) The prognostic importance of regional systolic function, as assessed by RWMS, compared with global function, as evaluated by LV ejection fraction, was assessed separately in our analysis. Our study also shows that the RWMS as well as LV ejection fraction provides powerful prognostic information in patients undergoing PCI after AMI. In addition, use of a BMS was another variable that was independently predictive in our system. Conflicting data have been published concerning use of BMSs vs. drug-eluting stents (DESs) in the setting of ST-segment elevation AMI.

23) In patients with ST-segment elevation AMI, however, steady improvements in outcomes have been realized with the evolution from BMSs to first-generation and now second-generation DESs in a mixed treatment comparison analysis of trial level data.

18) Additionally, Killip class ≥II at presentation, renal insufficiency, prior stroke, lower BMI, older age, prior coronary heart disease, and diabetes have been reported to influence short- and long-term mortality in patients with AMI.

19)20)21)22) These comorbid conditions were also independent predictors of a worse outcome in our study.

In fact, a large HR is required to meaningfully affect the C statistic of a model during prospective risk prediction; thus, the reclassification measures, such as the continuous-NRI, IDI, and the median improvement in risk score, may be more sensitive than that of the C statistic to quantify prognostic improvement of a system.

9)11)15) The continuous-NRI generalizes a summary measure proposed for reclassification tables by eliminating risk categories and calling any increase in model-based probability resulting from the addition of a new marker upward reclassification and any decrease for downward reclassification. Naturally, if the new variable is useful, it should increase the model-based probabilities for events and decrease the model-based probabilities for nonevents, leading to a higher discrimination slope and IDI as well as a higher NRI. The IDI is defined as a difference in the means of the model-based event probabilities (discrimination slopes between 2 models — one with, and the other without, the added variable), that is, a subtraction of the nonevents from the events. The median improvement in risk score is similar to the IDI except that it uses median instead of mean. Thus, we used the reclassification measures, such as the continuous-NRI, IDI, and median improvement in risk score, as well as the time-dependent ROC curve analyses and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test to show that the KorMI system has good predictive capacity compared to the most widely validated risk models for patients with AMI or ACS, such as the APEX AMI, CADILLAC, and GRACE algorithms.

One of several important clinical applications of the KorMI system is that this score identifies a group of patients with an ongoing high rate of adverse clinical events, even for those undergoing guideline-adherent optimal therapies. Identifying such high-risk patients may lead to use of more potent antiplatelet agents, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel, which significantly reduce adverse ischemic events.

24)

Several limitations of this study should be discussed. First, our findings must be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of events. Our study population may have tended to be at lower risk than that of the general AMI population. Thus, the study may have been underpowered to detect possible differences between the discriminative capacities of the risk scores. In addition, because of inclusion and exclusion criteria in this study, the present cohort may constitute a highly selected patient population, which obviating applicability of the KorMI scoring system to a general AMI population. Second, although a scoring system from a large data set tend to perform reasonably well when applied to independent data sets,

25) validation of a scoring system using external methods is as important as developing a new risk system.

26) Because, it is well recognized that deriving and validating a model on the same dataset will by definition lead to over optimistic estimates of the model's accuracy, and the precision of the fitted parameters will clearly be reduced as only a portion of the dataset is used for model derivation.

27) However, we could not access another more global AMI population. Therefore, the results should be considered hypothesis generating, and our risk system will need to be validated in a more generalized community population before widespread clinical adoption can be recommended. Third, we only had data on treatments given at discharge, and the compliance or dosages of optimal medications were unknown, which may have had a significant influence on clinical outcomes.

28)29) Also, the study lacks data on some factors that may be also important for clinical outcome, such as control rates of key risk factors during the follow-up period. Finally, the predictive value of the KorMI risk scoring system stops at 1-year after the index event. Further analysis of these patients with longer follow-up may be needed to strengthen the value of our risk scoring system. Despite these limitations, the large sample size, reflection of current real-world practice, and the overall consistency of predictive factors seen with previous studies support the reliability of our findings.

In conclusion, the KorMI risk scoring system is relatively simple to calculate prognostic tool specifically developed for patients surviving AMI, who are treated with contemporary guideline-adherent optimal therapies, in which 10 parameters (LV systolic dysfunction, BMS, Killip class ≥II at presentation, renal insufficiency, previous stroke, RWMS on 2-dimensional echocardiography, lower BMI, older age, prior coronary heart disease, and diabetes) were identified as independent predictors of 1-year all-cause death or MI. Its accurate prediction in terms of discrimination, goodness-of-fit, and the reclassification measures may make it a useful risk stratification tool during optimal triage, closer follow-up, and other more intense secondary preventive therapies in high-risk patients, even those treated with current guideline-adherent optimal therapies after AMI.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download